Glenoid Labrum

Original Editor - Priyanka Chugh

Top Contributors - Priyanka Chugh, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, Wendy Snyders, 127.0.0.1 and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

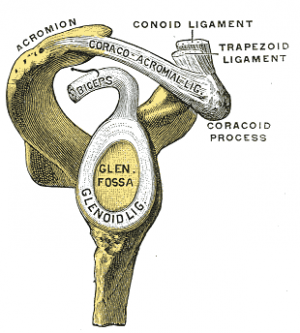

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous complex that attaches as a rim to the articular cartilage of the glenoid fossa. Its role is to: deepen and increase the surface area of the glenoid (acting as a static stabiliser of the glenohumeral joint); resist anterior and posterior movement and; attempting to block dislocation and subluxation at the maximal ranges of motion.[1]

The labrum is frequently involved in shoulder pathology, by acute trauma (eg shoulder dislocation) or, more commonly, repeated microtrauma eg shoulder subluxation.[2]

Structure[edit | edit source]

Glenoid labrum basics:

- Made of fibrocartilage, 3 mm thick and 4 mm wide (highly variable).

- On cross-section, the labrum is most commonly triangular, can be round.

- Inferior to the equatorial pole of the glenoid, the labrum gradually becomes rounder and smaller in contrast to superiorly , here it is more triangular in shape and larger.[1]

Attachments[edit | edit source]

- Superiorly: tendon of the long head of biceps brachii

- Anteriorly: superior glenohumeral ligament; middle glenohumeral ligament (variably)

- Inferiorly: inferior glenohumeral ligament consistenting of an anterior band, axillary pouch, and a posterior band[1]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with tears of the glenoid labrum present with an extensive range of non-specific symptoms including:

- Discomfort/pain, unable to pinpoint.

- Joint weakness and instability

- Clicking[1]

Anatomic Variants[edit | edit source]

- Inconsistent cross-sectional shape: blunted, cleaved, notched or flat.

- Medialised posterior labrum

- Anterior capsulolabral insertion variance[1]

Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

The labrum major functions include:

- To increase the contact area between humeral head and scapula.

- Help in the provision of the “Viscoelastic Piston” effect.

- Provides insertion for stabilizing structures, as a fibrous “crossroad”, with the labrum and ligaments working in synergy, each structure contributing to the varying with the position of the limb.[2]

Accuracy of Assessment[edit | edit source]

The ability to predict the presence of a glenoid labral tear by physical examination was compared with that of magnetic resonance imaging (conventional and arthro gram) and confirmed with arthroscopy. Main points of study:

- 37 men and 17 women (average age, 34 years) in the study group, 64% were throwing athletes and 61% recalled specific traumatic events.

- Clinical assessment included history with specific attention to pain with overhead activities, clicking, and instances of shoulder instability.

- Physical examination included the apprehension, relocation, load and shift, inferior sulcus sign, and crank tests.

- Shoulder arthroscopy confirmed labral tears in 41 patients (76%).

- Magnetic resonance imaging produced a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 85%.

- Physical examination yielded a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 85%.

Conclusion: Physical examination is more accurate in predicting glenoid labral tears than magnetic resonance imaging. In this era of cost containment, completing the diagnostic workup in the clinic without expensive ancillary studies allows the patient's care to proceed in the most timely and economic fashion.[3]

Particular Places[edit | edit source]

Labral injuries are named according to localisation

- Superior labrum: SLAP lesion

- Anteroinferior labrum: Bankart lesion; Perthes lesion; Glenolabral articular disruption lesion (GLAD); Anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion (ALPSA)

- Posteroinferior labrum: Reverse Bankart lesion; Posterior GLAD; Posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion lesion (POLPSA); Kim lesion (superficial tears between the posterior glenoid labrum and glenoid articular cartilage without labral detachment)

- Circumferential labral lesion

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Postoperative Treatment and Results[edit | edit source]

Typically requires six months and often as long as 12 months to return to throwing after surgical repair of a SLAP lesion. Healing must not be rushed. The patient should work through the appropriate stages of rehabilitation gradually and clinicians must guard against the patient progressing prematurely. Given the complexity and importance of post-operative rehabilitation, patients are best served by participating in a rehabilitation program under the supervision of a knowledgeable physical therapist, athletic trainer, or comparable clinician.

The post-operative rehabilitation program is typically divided into three stages:

- Phase 1 Maximal protection phase (approximately six weeks duration)

- Phase 2 Moderate protection phase (approximately six weeks duration)

- Phase 3 Minimum protection phase (approximately 14 weeks duration)

Phase 1 Maximal Protection Phase[edit | edit source]

The maximal protection phase begins the day after surgery until around six weeks. During this phase the primary goal is to protect the surgical repair from re-injury and to minimize pain and inflammation. The patient is typically in a sling for the full six weeks; avoiding any motion that loads the biceps tendon is critical. The patient begins to perform passive and active assisted range of motion (ROM) exercises during this phase but these are limited. Protected motion begins with passive motion below 90 degrees of shoulder flexion and abduction, and progresses gradually after the first two weeks. Limited active motion is introduced gradually. Toward the end of this stage, the patient begins to perform some basic isometric strength exercises.

Phase 2 Moderate Protection Phase[edit | edit source]

The moderate protection phase begins at approximately week seven and continues through week 12. During this phase, one major goal is to regain full active range of motion. Around week 10, active loading of the biceps tendon can begin. If full ROM is not obtained with the basic program, additional focused stretching and mobilization exercises may be required. Increasing levels of resistance are used for scapular and rotator cuff exercises. Exercises for developing core strength are performed during this phase.

Phase 3 Minimum Protection Phase[edit | edit source]

The minimum protection phase begins at approximately week 13 and continues through week 26. During this phase, the patient may gradually resume throwing or overhead occupational activities until full function is restored. Throwing from a mound may begin around 24 to 28 weeks after surgery in most cases. It is critical that full shoulder mobility is achieved. Full strength and motion of the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff muscles should be achieved before full activity is resumed. To prevent reinjury, it is important that a pitcher’s throwing mechanics be assessed and any problems resolved, and that appropriate guidelines regarding the type and number of pitches thrown be followed .

For the patient who follows up with a primary care or sports medicine physician, failure to progress through the phases in a reasonable time frame (approximately three months for phases 1 or 2 and six months for phase 3) merits consultation with the orthopedic surgeon who completed the repair. Similarly, if the patient develops unexpected pain or dysfunction during the post-operative rehabilitation, the patient should return to their orthopedic surgeon for evaluation. The surgeon should have the final say about whether the patient is ready to resume full activity.

A systematic review of studies of the management of Type 2 SLAP tears (506 patients included) found that 83 percent of patients reported good-to-excellent results following operative repair . However, only 73 percent of patients returned to their prior level of function, while only 63 percent of overhead throwing athletes returned to their previous level of play. Should primary repair fail, biceps tenodesis often relieves pain. About 40 percent of patients report an excellent outcome with this surgery, while approximately 4 percent experience significant complications . Common long-term disabilities after a failed surgical repair include pain and instability with overhead or abducted and externally rotated shoulder positions. It is unclear whether SLAP tears increase the risk for glenohumeral osteoarthritis.[4]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Radiopedia Glenoid Labrum Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/glenoid-labrum (accessed 10.1.2023)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Clavert P. Glenoid labrum pathology. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2015 Feb 1;101(1):S19-24.Available:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877056814003259 (accessed 10.1.2023)

- ↑ http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/036354659602400205

- ↑ https://www.uptodate.com/contents/superior-labrum-anterior-posterior-slap-tears