Fitness and Exercise Strategies for Persons With Parkinson’s: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

== Neuromotor Function == | == Neuromotor Function == | ||

[[File:Elderly-people-doing-balance-exercise.jpg|left|thumb|Balance Training|alt=|280x280px]] | [[File:Elderly-people-doing-balance-exercise.jpg|left|thumb|Balance Training|alt=|280x280px]] | ||

Exercise to improve neuromotor function may include '''balance''' training, '''agility''' work, '''coordination''' practice, '''gait''' training, and '''dual task''' training. This could include activities such as multidirectional stepping, and anticipatory and reactive postural adjustment training, for example. Specific balance training is effective at improving postural control for persons with Parkinson's.<ref>Santos SM, Rubens A, Silva da, Terra MB, Almeida IA, Lúcio B, et al. Balance versus resistance training on postural control in patients with parkinson's disease: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017;53(2).</ref>Other exercise programs already mentioned above, such as tai chi, yoga, boxing, and dancing, also fit within this category. '''Ai chi''' is a form of tai chi that is water-based, and there is evidence this is effective at improving balance, mobility, motor function, and quality of life for persons with Parkinson's.<ref>Kurt EE, Büyükturan B, Büyükturan Ö, Erdem HR, Tuncay F. Effects of Ai Chi on balance, quality of life, functional mobility, and motor impairment in patients with parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;40(7):791–7.</ref> | Exercise to improve neuromotor function may include '''balance''' training, '''agility''' work, '''coordination''' practice, '''gait''' training, and '''dual task''' training. This could include activities such as multidirectional stepping, and anticipatory and reactive postural adjustment training, for example. Specific balance training is effective at improving postural control for persons with Parkinson's.<ref>Santos SM, Rubens A, Silva da, Terra MB, Almeida IA, Lúcio B, et al. Balance versus resistance training on postural control in patients with parkinson's disease: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017;53(2).</ref>Other exercise programs already mentioned above, such as tai chi, yoga, boxing, and dancing, also fit within this category. '''Ai chi''' is a form of tai chi that is water-based, and there is evidence this is effective at improving balance, mobility, motor function, and quality of life for persons with Parkinson's.<ref>Kurt EE, Büyükturan B, Büyükturan Ö, Erdem HR, Tuncay F. Effects of Ai Chi on balance, quality of life, functional mobility, and motor impairment in patients with parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;40(7):791–7.</ref><blockquote>Video demonstration of balance training (see dual task training starting at 6:51): | ||

</blockquote> | |||

== Task-Specific Circuit Training == | == Task-Specific Circuit Training == | ||

Revision as of 01:14, 20 January 2022

Original Editor - Thomas Longbottom based on the course by Z Altug

Top Contributors - Thomas Longbottom, Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell and Lucinda hampton

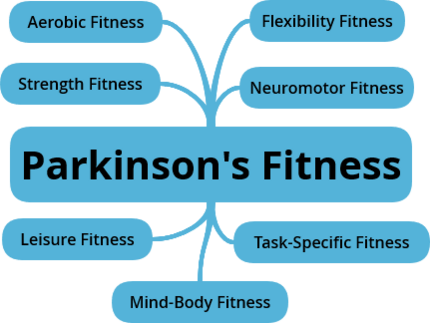

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Approximately 10 million people around the world are currently living with Parkinson’s Disease.[1] Meta-analysis of worldwide data reveals that the prevalence of Parkinson’s Disease increases with age, quadrupling from a level of almost 0.5% in the seventh decade of life to approximately 2% for those over the age of 80.[2] Other sources report that Parkinson's affects 1.5-2% of the population over the age of 60.[3] Parkinson’s is associated with the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain, and it is typified clinically by resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia along with a number of non-motor features such as anosmia, sleep behaviour disorder, depression, autonomic dysfunction, and cognitive dysfunction.[4] The aetiology of this disease is not fully understood, but there is some combination of environmental and genetic factors presumed to be causative.[4] Among these are various lifestyle factors such as tobacco use, dietary intake, and physical activity.[5][6]

According to the Lifestyle Medicine Handbook, Lifestyle Medicine involves the use of evidence-based lifestyle therapeutic approaches to treat, reverse, and prevent lifestyle-related chronic disease.[7] These include:

- A predominantly whole food, plant-based diet

- Regular physical activity

- Adequate sleep

- Stress management

- Social connections

- Avoidance of risky substance abuse[7]

The aim of Lifestyle Medicine is to treat the underlying causes of disease rather than just addressing the symptoms. This involves helping patients learn and adopt healthy behaviours. Lifestyle interventions have the potential to impact the prognosis of many chronic diseases, leading not only to a better quality of life for many but also potentially reducing their costs to the healthcare system.[8] While a tendency to think of Lifestyle Medicine as being the domain of the physician is understandable, other providers such as dietitians, social workers, behavioural therapists, and lifestyle coaches are also integral.[8] It is also well within the scope of the physiotherapist, with diet and nutrition being key elements in many of the conditions managed by physiotherapists, with physiotherapists poised as experts in exercise and movement, and with prevention, health promotion, fitness and wellness being crucial aspects of physiotherapy care.[9] The focus of this module will be on discussing strategies for persons with Parkinson's related to fitness. This topic will be discussed in terms of various components including mind-body, aerobic, strength, flexibility, neuromotor, task-specific, and leisure fitness.

Mind-Body Fitness[edit | edit source]

A mind-body fitness regimen can include a variety of activities that combine body movement with mental focus. The practice of controlled breathing is often a feature.

- Yoga is one such practice involving assuming and holding various physical postures while performing coordinated, diaphragmatic breathing.[10]There is evidence that yoga may help manage depression, reduce fall risk, and improve motor function in persons with Parkinson's.[11][12][13]

- Traditional martial arts such as Tai chi and Karate may improve balance and fall prevention as well as quality of life.[14][15] Tai chi, also known as shadow boxing, involves gentle, slow movements and stretching combined with controlled breathing and meditation. Karate, Japanese for "empty hand", employs the practice of stances along with kicking, striking, and defensive blocking movements with the extremities. Qigong is another style of Chinese martial art form combining gentle flowing exercises with mindfulness, and a particular form of qigong is Ba Duan Jin, meaning the "Eight Section Brocades". This uses a combination of eight movements with deep, slow breathing, and it is considered a form of medical qigong intended to improve health.[16] There is evidence that qigong and Baduanjin qigong may improve gait and sleep quality in persons with Parkinson's.[17][18]

- Pilates, initially developed for dancers, is an exercise method that emphasizes abdominal and low back/hip muscle tone.[19] It can improve balance and physical function in a person with Parkinson's.[20]

- The Feldenkrais Method is another mindful movement practice with an emphasis on the quality of movement that may result in improved quality of life for persons with Parkinson's.[21]A similar method is the Alexander technique, one that puts more focus on dynamic posture. There is some evidence that persons with Parkinson's may experience improvements in self-rated disability.[22]

- Meditative or reflective walking is another approach to mind-body fitness that may have some positive effects on mood, affect and cognition.[23][24]This activity can be as simple as walking outdoors while focusing on the sights, sounds and smells of nature, of feeling the wind in your face or the sensations through the feet.[10] Use of a labyrinth walking path is a novel way to participate in reflective walking.[25]

Aerobic Fitness[edit | edit source]

Aerobic exercise can be performed using a variety of activities such as treadmill or overground walking, stationary cycling, elliptical rowers, seated reciprocal stepping, upper limb cycling, swimming, and even dancing.[10] There is evidence that high intensity exercise can result in significant improvements in functional mobility.[26]A program of brisk walking and balance training can improve motor function and gait ability in persons with Parkinson's.[27]Aerobic exercise may also be beneficial in terms of protective effects against depression[28] and of enhanced motor memory consolidation.[29]

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) aerobic exercise guidelines:[30]

- Exercise frequency - 3 to 4 days per week.

- Exercise duration - 30 minutes of continuous or accumulated exercise

- Exercise intensity - to be determined by the healthcare or fitness professional

Strength[edit | edit source]

Strength exercise, including resistance training on weight machines, elastic resistance exercise, and free weight and bodyweight exercise can lead not only to strengthening but improved physical function, reduced depression, and improved overall quality of life in persons with Parkinson's.[31][32]

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) aerobic exercise guidelines:[30]

- Exercise frequency - 2 to 3 days per week.

- Exercise duration/repetition - 1 to 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions, beginning with 1 set and building to 3 sets.

- Exercise intensity - to be determined by the healthcare or fitness professional

Flexibility[edit | edit source]

A flexibility program for a person with Parkinson's can include slow static stretches for all major muscle groups. Flexibility exercise can improve functional performance and activities of daily living in persons with Parkinson's, enhancing capability for bending to tie shoes, donning and doffing clothing, and reaching for items either overhead or on the floor.[33] [10]

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) aerobic exercise guidelines:[30]

- Exercise frequency - 2 to 3 days per week.

- Exercise duration/repetition - 10 to 30 second holds with 2 to 4 repetitions of each stretch.

- Exercise intensity - stretch to the point of slight discomfort

Neuromotor Function[edit | edit source]

Exercise to improve neuromotor function may include balance training, agility work, coordination practice, gait training, and dual task training. This could include activities such as multidirectional stepping, and anticipatory and reactive postural adjustment training, for example. Specific balance training is effective at improving postural control for persons with Parkinson's.[34]Other exercise programs already mentioned above, such as tai chi, yoga, boxing, and dancing, also fit within this category. Ai chi is a form of tai chi that is water-based, and there is evidence this is effective at improving balance, mobility, motor function, and quality of life for persons with Parkinson's.[35]

Video demonstration of balance training (see dual task training starting at 6:51):

Task-Specific Circuit Training[edit | edit source]

Circuit training can be an effective approach to engaging the person with Parkinson's in a variety of exercise activities, potentially contributing to enhanced motor learning. This approach involves moving between multiple activities with varying amounts of rest or stretching between.[10] The virtues of variable practice and performance in a distributed versus blocked practice manner may be beneficial in terms of motor learning. Evidence supports that task-oriented circuit training can improve balance and gait performance, and, by extension, balance confidence and quality of life for persons with Parkinson's.[36]

Sample Circuit Training Program:[10]

- Start with a 5-minute warm-up on a stationary bike or treadmill.

- Perform sit to stand x 10 repetitions.

- Perform sit to stand and walk x 6 meters.

- Walk up and down incline surfaces.

- Step up and down from varied-height surfaces.

- Walk while weaving back and forth between cones x 6 meters.

- Walk up and down stairs.

- Reach in multiple directions in sitting and standing.

- Step in multiple directions in standing.

- Perform boxing movements.

- Finish with a 5-minute cool-down on a stationary bike or treadmill.

Leisure Fitness[edit | edit source]

Activities that could be considered leisure fitness activities include Nordic walking, dancing, table tennis, and video exergames. Nordic walking employs the use of trekking poles for a total-body version of walking that encourages greater use of the upper as well as the lower extremities while facilitating trunk rotation. It is effective at improving motor function as well as some of the non-motor symptoms associated with Parkinson's such as apathy, depression, and fatigue.[37]Dancing also has the potential to improve gait, cognition, balance, functional mobility, and fatigue.[38][39]Participation in the activity of table tennis has the potential to improve motor function and activities of daily living in persons with Parkinson's.[40] Participation in video exergames that involve various physical components along with facilitating dual-task engagement can improve motor function, balance, and cognition and executive function as well as processing speed.[41] These have the advantage of being fun, encouraging increased adherence and participation.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- LSVT-BIG for Parkinson's: https://www.lsvtglobal.com/LSVTBig

- Parkinson Wellness Recovery: https://www.pwr4life.org/

- Rock Steady Boxing: https://www.rocksteadyboxing.org/

- Ping Pong Parkinson: https://www.pingpongparkinson.org/about.html

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Statistics [Internet]. Parkinson's Foundation. [cited 2021Dec28]. Available from: https://www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Statistics

- ↑ Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TDL. The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders 2014;29(13):1583–90.

- ↑ Venes D, Taber CW. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Simon DK, Tanner CM, Brundin P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2020;36(1):1–2.

- ↑ Ritz B, Ascherio A, Checkoway H, Marder KS, Nelson LM, Rocca WA, et al.. Pooled Analysis of Tobacco Use and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology [Internet] 2007;64(7):990.

- ↑ Paul KC, Chuang Y, Shih I, Keener A, Bordelon Y, Bronstein JM, et al.. The association between lifestyle factors and Parkinson's disease progression and mortality. Movement Disorders 2019;34(1):58–66.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Frates B, Bonnet JP, Joseph R, Peterson JA. Lifestyle Medicine Handbook: An introduction to the power of Healthy Habits. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning; 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bodai B. Lifestyle Medicine: A Brief Review of Its Dramatic Impact on Health and Survival. The Permanente Journal 2017;22(1).

- ↑ Worman R. Lifestyle medicine: The role of the physical therapist. The Permanente Journal. 2020;24:18.192.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Z Altug. Parkinson's Lifestyle Medicine - Fitness Strategies. Physioplus Course. 2022.

- ↑ Sagarwala R, Nasrallah HA. The effects of yoga on depression and motor function in patients with Parkinson's disease: A review of controlled studies. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2020; 32(3):209-215.

- ↑ Van Puymbroeck M, Walter A, Hawkins BL, Sharp JL, Woschkolup K, Urrea-Mendoza E, et al. Functional improvements in parkinson’s disease following a randomized trial of yoga. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;2018:1–8.

- ↑ Kwok JYY, Kwan JCY, Auyeung M, Mok VCT, Lau CKY, Choi KC, et al. Effects of Mindfulness Yoga vs Stretching and Resistance Training Exercises on Anxiety and Depression for People With Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurology 2019;76(7):755.

- ↑ Gao Q, Leung A, Yang Y, Wei Q, Guan M, Jia C, et al. Effects of Tai Chi on balance and fall prevention in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 2014;28(8):748–53.

- ↑ Fleisher JE, Sennott BJ, Myrick E, Niemet CJ, Lee M, Whitelock CM, et al. KICK OUT PD: Feasibility and quality of life in the pilot karate intervention to change kinematic outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease. PLOS ONE 2020;15(9):e0237777.

- ↑ Long L. Ba Duan Jin exercise, how to practice baduanjin [Internet]. China Educational Tours. China Educational Tours; 2021 [cited 2022Jan17]. Available from: https://www.chinaeducationaltours.com/guide/culture-qigong-ba-duan-jin.htm

- ↑ Wassom DJ, Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Liu W. Qigong exercise may improve sleep quality and gait performance in parkinson's disease: A pilot study. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;125(8):578–84.

- ↑ Xiao C-M, Zhuang Y-C. Effect of health Baduanjin Qigong for mild to moderate Parkinson's disease. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2016;16(8):911–9.

- ↑ Gilmerm. Everything you want to know about pilates [Internet]. Cleveland Clinic. Cleveland Clinic; 2020 [cited 2022Jan18]. Available from: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/everything-you-want-to-know-about-pilates/

- ↑ Suárez-Iglesias D, Miller KJ, Seijo-Martínez M, Ayán C. Benefits of Pilates in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2019;55(8):476.

- ↑ Teixeira-Machado L, Araújo FM, Cunha FA, Menezes M, Menezes T, Melo DeSantana J. Feldenkrais method-based exercise improves quality of life in individuals with Parkinson's disease: a controlled, randomized clinical trial. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2015;21(1):8-14.

- ↑ Stallibrass C, Sissons P, Chalmers C. Randomized controlled trial of the Alexander Technique for idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Clinical Rehabilitation 2002;16(7):695–708.

- ↑ Gotink RA, Hermans KSFM, Geschwind N, De Nooij R, De Groot WT, Speckens AEM. Mindfulness and mood stimulate each other in an upward spiral: a mindful walking intervention using experience sampling. Mindfulness 2016;7(5):1114–22.

- ↑ Yang C-H, Hakun JG, Roque N, Sliwinski MJ, Conroy DE. Mindful walking and cognition in older adults: A proof of concept study using in-lab and ambulatory cognitive measures. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2021;23:101490.

- ↑ Lizier D, Silva-Filho R, Umada J, Melo R, Neves A. Effects of Reflective Labyrinth Walking Assessed Using a Questionnaire. Medicines 2018;5(4):111.

- ↑ Miller Koop M, Rosenfeldt AB, Alberts JL. Mobility improves after high intensity aerobic exercise in individuals with parkinson's disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2019;399:187–93.

- ↑ Mak MKY, Wong-Yu ISK. Six-month community-based brisk walking and balance exercise alleviates motor symptoms and promotes functions in people with parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Parkinson's Disease. 2021;11(3):1431–41.

- ↑ Altmann LJP, Stegemöller E, Hazamy AA, Wilson JP, Bowers D, Okun MS, et al.. Aerobic Exercise Improves Mood, Cognition, and Language Function in Parkinson’s Disease: Results of a Controlled Study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2016;22(9):878–89.

- ↑ Wanner P, Winterholler M, Gaßner H, Winkler J, Klucken J, Pfeifer K, et al. Acute exercise following skill practice promotes motor memory consolidation in parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2021;178:107366.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, 11th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021: 412-440.

- ↑ Chung CLH, Thilarajah S, Tan D. Effectiveness of resistance training on muscle strength and physical function in people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation 2016;30(1):11–23.

- ↑ Lima TA, Ferreira-Moraes R, Alves WMGDC, Alves TGG, Pimentel CP, Sousa EC, et al. Resistance training reduces depressive symptoms in elderly people with Parkinson disease: A controlled randomized study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2019;29(12):1957–67.

- ↑ Schenkman M, Hall DA, Barón AE, Schwartz RS, Mettler P, Kohrt WM. Exercise for People in Early- or Mid-Stage Parkinson Disease: A 16-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy 2012;92(11):1395–410.

- ↑ Santos SM, Rubens A, Silva da, Terra MB, Almeida IA, Lúcio B, et al. Balance versus resistance training on postural control in patients with parkinson's disease: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017;53(2).

- ↑ Kurt EE, Büyükturan B, Büyükturan Ö, Erdem HR, Tuncay F. Effects of Ai Chi on balance, quality of life, functional mobility, and motor impairment in patients with parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;40(7):791–7.

- ↑ Soke F, Guclu-Gunduz A, Kocer B, Fidan I, Keskinoglu P. Task-oriented circuit training combined with aerobic training improves motor performance and balance in people with Parkinson′s disease. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2019;121(2):535–43.

- ↑ Cugusi L, Solla P, Serpe R, Carzedda T, Piras L, Oggianu M, et al. Effects of a Nordic walking program on motor and non-motor symptoms, functional performance and body composition in patients with parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;37(2):245–54.

- ↑ Kalyani HHN, Sullivan K, Moyle G, Brauer S, Jeffrey ER, Roeder L, et al. Effects of dance on gait, cognition, and dual-tasking in parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Parkinson's Disease. 2019;9(2):335–49.

- ↑ Rios Romenets S, Anang J, Fereshtehnejad S-M, Pelletier A, Postuma R. Tango for treatment of motor and non-motor manifestations in parkinson's disease: A Randomized Control Study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2015;23(2):175–84.

- ↑ Inoue K, Fujioka S, Nagaki K, Suenaga M, Kimura K, Yonekura Y, et al. Table tennis for patients with parkinson’s disease: A single-center, prospective pilot study. Clinical Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2021;4:100086.

- ↑ Costa MTS, Vieira LP, Barbosa EO, et al. Virtual Reality-Based Exercise with Exergames as Medicine in Different Contexts: A Short Review. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2019;15:15-20.