Exercise and Protein Supplements: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

= How protein metabolizes and protein's effects on the body = | = How protein metabolizes and protein's effects on the body = | ||

Protein metabolism in the body occurs differently from the other macronutrients, as there is no type of storage for proteins. Like carbohydrates and fat, proteins are composed of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen, but they also contain the element Nitrogen. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and are connected by peptide bonds to form either, dipeptides, tripeptides, oligopeptides, or polypeptides | Protein metabolism in the body occurs differently from the other macronutrients, as there is no type of storage for proteins. Like carbohydrates and fat, proteins are composed of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen, but they also contain the element Nitrogen. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and are connected by peptide bonds to form either, dipeptides, tripeptides, oligopeptides, or polypeptides. Amino acids are also the usable form that is necessary for digestion to occur. There are 9 essential amino acids that must be consumed, and 11 non-essential amino acids that can be synthesized in the body. A complete protein contains all of the essential amino acids, while an incomplete protein lacks one or more essential amino acids. Complete proteins are typically seen in animal products, while incomplete proteins are commonly seen in plant sources. <br> | ||

Unlike the other macronutrients where digestion begins in the mouth, protein metabolism starts in the stomach. In the stomach the enzyme pepsinogen in converted to the active pepsin form when in the presence of the highly acidic hydrochloric acid (HCl). Pepsin begins to break down the peptide bonds to form dipeptides and amino acids necessary for digestion. Enzymes, including Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, and Carboxypeptidase, from the pancreas and small intestine are also secreted when needed to break any remaining peptide bonds that escaped the stomach. The amino acids are then absorbed in the small intestine and released in the blood stream. <references /> [13]<br> | Unlike the other macronutrients where digestion begins in the mouth, protein metabolism starts in the stomach. In the stomach the enzyme pepsinogen in converted to the active pepsin form when in the presence of the highly acidic hydrochloric acid (HCl). Pepsin begins to break down the peptide bonds to form dipeptides and amino acids necessary for digestion. Enzymes, including Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, and Carboxypeptidase, from the pancreas and small intestine are also secreted when needed to break any remaining peptide bonds that escaped the stomach. The amino acids are then absorbed in the small intestine and released in the blood stream. <references /> [13]<br> | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 30 November 2015

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Containers of protein powders line the shelves of many supplement stores and are typically a highly purchased product. Protein supplements can be used for a variety of reasons such to help build muscle mass, help with exercise recovery, and can even be used as a meal replacement. Due to the wide variety of usages, this supplement will be used by many types of people and found commonly in a physical therapy clinic. As a physical therapist it is crucial to know how protein metabolizes, the different types of protein supplements that are commonly sold, the effects on timing of ingestion of protein supplements, how protein effects different types of exercise, how age and gender influence protein supplementation, and lastly any additional side effects protein supplements may have.

Types of Protein Supplements[edit | edit source]

Soy protein supplementation has had a lot of controversy over its effect on musle through use with resistance training, but also the postives and negatives of some of its potential side effects. The main content of soy protein supplements is the soy bean. In a 2006 study, the effects of whey and soy protein with resistance training young men and women in comparison to a blinded control group. The results showed that soy protein in combination with resistance training produces the same effects as whey protein supplementation. [1]

How protein metabolizes and protein's effects on the body[edit | edit source]

Protein metabolism in the body occurs differently from the other macronutrients, as there is no type of storage for proteins. Like carbohydrates and fat, proteins are composed of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen, but they also contain the element Nitrogen. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, and are connected by peptide bonds to form either, dipeptides, tripeptides, oligopeptides, or polypeptides. Amino acids are also the usable form that is necessary for digestion to occur. There are 9 essential amino acids that must be consumed, and 11 non-essential amino acids that can be synthesized in the body. A complete protein contains all of the essential amino acids, while an incomplete protein lacks one or more essential amino acids. Complete proteins are typically seen in animal products, while incomplete proteins are commonly seen in plant sources.

Unlike the other macronutrients where digestion begins in the mouth, protein metabolism starts in the stomach. In the stomach the enzyme pepsinogen in converted to the active pepsin form when in the presence of the highly acidic hydrochloric acid (HCl). Pepsin begins to break down the peptide bonds to form dipeptides and amino acids necessary for digestion. Enzymes, including Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, and Carboxypeptidase, from the pancreas and small intestine are also secreted when needed to break any remaining peptide bonds that escaped the stomach. The amino acids are then absorbed in the small intestine and released in the blood stream.

- ↑ Candow DG, Burke NC, Smith-Palmar T, Bure DG. Effect of whey and soy protein supplementation combined with resistance training in young adults. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2006; 15:233-244. Full version: http://journals.humankinetics.com/AcuCustom/Sitename/Documents/DocumentItem/5956.pdf (accessed 19 Nov 2006).

[13]

Proteins are responsible for a number of roles in the body. However, while carbohydrate and fats can be used for energy, proteins do not supply energy directly to the body. Instead proteins are utilized to form blood transporters, enzymes, participate in hormonal regulation, fluid balance, and acid-base balance, and act as a structural component in connective tissue and muscle [12].

The recommendations for protein intake vary during different stages of life, gender, and activity level. The Estimated Average Requirements (EAR) for protein ranges from anywhere from 0.66 to about 1 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is similar to the EAR and suggests the daily requirement for adult men and women ranges from 46 to 56 grams each day. Different ages and stages of life are also important to consider when recommending protein intake. For example, during adolescence, lactation, and in the elderly population the ranges vary [13].

Timing of protein supplementation[edit | edit source]

Before exercise:

During exercise:

After exercise:

In one study researchers investigated the impact of amino acid (lysine, proline, alanine, and arginine) and/or conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) supplements administered before and after aerobic exercise on body weight, percentage body fat, waist and hip circumference, triglycerides and LDL-cholesterol levels [1]. When compared to the placebo group, the waist and hip circumference and BMI of the experimental group after aerobic exercise was a clinically significant.

Types of exercise and protein supplementation[edit | edit source]

Age and the affects of protein supplementation[edit | edit source]

Gender and the affects of protein supplementation[edit | edit source]

Additional Side Effects[edit | edit source]

In addition to its effects on muscles, the use of protein supplements may also come with a number of other side effects, both chronic and acute. Several studies have shown that increased protein intake through the use of protein supplements can have the effect of lowering both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Its use may therefore be beneficial in managing the blood pressure of those with hypertension. However, one needs to exercise caution with protein supplementation for those whose blood pressure is already low or who are taking medication that lowers blood pressure, as it may increase hypotension-related risks.[2][3][4][5][6]

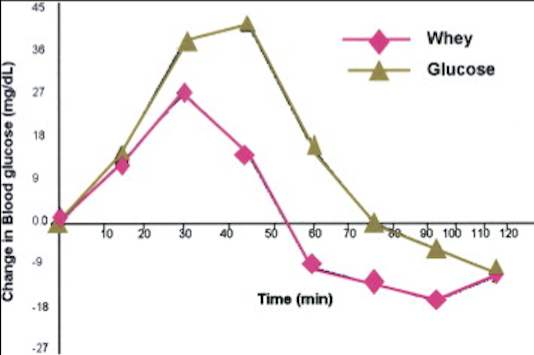

Because protein intake also causes an increase in blood insulin levels, studies have shown that it can significantly lower blood sugar levels. This effect is most pronounced following the ingestion of whey protein, but is still noticeable with the ingestion of protein from other sources.[7][8][9][10] The following graph is from a study comparing blood glucose levels after ingesting a plain glucose drink with blood glucose levels after ingesting the same glucose drink mixed with whey protein:

Blood glucose levels were clearly much lower when whey protein was ingested.[11] It is therefore important to be mindful of this effect on blood sugar levels when one already has low blood sugar or when one may be taking insulin for diabetes. Failing to do so could potentially increase dangerous hypoglycemia-related risks.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Michishita, T., Kobayashi, S., Katsuya, T, Ogihara, T., Kawabuchi, K. (2010). Evaluation of the antiobesity effects of an amino acid mixture and conjugated linoleic acid on exercising healthy overweight humans: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of International Medical Research, 38, 844-859.

- ↑ Nussberger J. (2007). Blood pressure lowering tripeptides derived from milk protein. Therapeutische Umschau, 64(3), 177-179. doi:10.1024/0040-5930.64.3.177

- ↑ Pal, S., Ellis, V. (2010). The chronic effects of whey proteins on blood pressure, vascular function, and inflammatory markers in overweight individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring), 18(7), 1354-1359. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.397

- ↑ He, J., Wofford, M., Reynolds, K., Chen, J., Chen, C., Myers, L., . . . Whelton, P. (2011). Effect of dietary protein supplementation on blood pressure: A randomized, controlled trial. Circulation, 124(5), 589-595. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009159

- ↑ He, J., Gu, D., Wu, X., Chen, J., Duang, X., Chen, J., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Whelton, P. (2005). Effect of soybean protein on blood pressure: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 143(1), 1-9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00004

- ↑ Teunissen-Beekman, K., Dopheide, J., Geleijnse, J., Bakker, S., Brink, E., Leeuw, P., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Baak, M. (2012). Protein supplementation lowers blood pressure in overweight adults: Effect of dietary proteins on blood pressure (PROPRES), a randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95(4), 966-971. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.029116

- ↑ Pal, S., Ellis, V. (2010). The acute effects of four protein meals on insulin, glucose, appetite and energy intake in lean men. British Journal of Nutrition, 104(8), 1241-1248. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510001911

- ↑ Frid, A.H., Nilsson, M., Holst, J.J., &amp;amp; Bjorck, M.E. (2005). Effect of whey on blood glucose and insulin responses to composite breakfast and lunch meals in type 2 diabetic subjects. American Society for Clinical Nutrition 82(1), 69-75.

- ↑ O’Keefe, J.H., Gheewala, N.M., &amp;amp; O’Keefe, J.O. (2008). Dietary Strategies for Improving Post-Prandial Glucose, Lipids, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Health Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51(3), 249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016.

- ↑ Petersen, B.L., Ward, L.S., Bastian, E.D., Jenkins, A.L., Campbell, J., &amp;amp; Vuksan, V. (2009). A whey protein supplement decreases post-prandial glycemia. Nutrition Journal 8(47). doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-47

- ↑ O’Keefe, J.H., Gheewala, N.M., &amp;amp; O’Keefe, J.O. (2008). Dietary Strategies for Improving Post-Prandial Glucose, Lipids, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Health Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51(3), 249-255. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016.

13. Chowanadisai, Winyoo. "Protein metabolism." Oklahoma State University. Human Science Building. Stillwater, OK. 20 January 2015. Class Lecture.

14. Williams, Joshua. "Nutrients for physical activity". University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Oklahoma City, OK. 9 September 2015. Class Lecture.