Developing a Social Media Resource to Promote Physical Activity in Teenage Girls: Difference between revisions

Helen Power (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Helen Power (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

<br>In adolescent girls the most cited determinants of PA were as follows: <br>• '''Time constraint-''' Teenage girls report being “too busy” and having conflicts with other activities which are preventing them from exercising.<ref name="H10">ALLISON, K.R., DWYER, J.J.M. and MAKIN, S., 1999. Perceived barriers to physical activity among high school students. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 608-615.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> <ref name="H11">SALLIS, J.F., PROCHASKA, J. J. and TAYLOR, C., 1999. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 963-975.</ref> <ref name="H12">NEUMARK-SZTAINER, D., STORY, M., HANNAN, P..J., THARP, T. and REX, J., 2003. Factors associated with changes in physical activity: a cohort study of inactive adolescent girls. Arch Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine. vol. 157, pp. 803-810.</ref> <ref name="H13">ROBBINS, L.B. and KAZANIS, A.S., 2003. Barriers to physical activity perceived by adolescent girls. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 206-212.</ref>These findings suggest the importance of helping adolescent learn time management strategies. Include tips on the Facebook page advocating making PA a priority and recommend ways to fit PA into their daily lives i.e. engaging in 3 x 10 minutes of PA spread throughout their day or by keep activity logs. </span> | <br>In adolescent girls the most cited determinants of PA were as follows: <br>• '''Time constraint-''' Teenage girls report being “too busy” and having conflicts with other activities which are preventing them from exercising.<ref name="H10">ALLISON, K.R., DWYER, J.J.M. and MAKIN, S., 1999. Perceived barriers to physical activity among high school students. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 608-615.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> <ref name="H11">SALLIS, J.F., PROCHASKA, J. J. and TAYLOR, C., 1999. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 963-975.</ref> <ref name="H12">NEUMARK-SZTAINER, D., STORY, M., HANNAN, P..J., THARP, T. and REX, J., 2003. Factors associated with changes in physical activity: a cohort study of inactive adolescent girls. Arch Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine. vol. 157, pp. 803-810.</ref> <ref name="H13">ROBBINS, L.B. and KAZANIS, A.S., 2003. Barriers to physical activity perceived by adolescent girls. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 206-212.</ref>These findings suggest the importance of helping adolescent learn time management strategies. Include tips on the Facebook page advocating making PA a priority and recommend ways to fit PA into their daily lives i.e. engaging in 3 x 10 minutes of PA spread throughout their day or by keep activity logs. </span> | ||

• '''Support from parents, teachers and peers - '''Parents and teachers need to hear how much their support matters to their children, even at high school level.<ref name="H12" /> In addition to parental support, peer influences appear to be very important with respect to participation in organised sport.<ref name="H15">KAHL, H.W. and HOBBS, K., 1998. Development of physical activity behaviour among children and adolescents. Paediatrics. vol. 101, pp. 549-554.</ref>Influences of a best friend were more highly associated with PA behaviour than influences of parents. <ref name="H15" />The facebook page should encourage the social aspect of PA and emphasis peer support and participation as well as exercising with groups. <br>•'''Self-efficacy to be physically active- '''Another strong predictor of PA is self-perception and self-efficacy to be physically active.<ref name="H16">DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SAUNDERS, R. FELTON, G., WARD, D.S., DOWDA, M. and PATE, R.R, 2004. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 628-636.</ref>Bandura’s self-efficacy theory<ref name="H7" /> suggested that confidence in a personal ability to carry out a behaviour, influences adoption of that behaviour. Consequently girls who have high self-efficacy in their capabilities to be physically active will recognise fewer barriers to exercise or be less affected by them, be more likely to perceive the benefits of PA, and be more likely to enjoy it.<ref name="H17">DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SALLIS, J.F., DUNN, A.L. BIRNBAUM, A.S., WELK, G.J., BEDIMO-RUNG, A.L., VOORHEES, C.C. and JOBE, J.B., 2005. Self-management strategies mediate self-efficacy and physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. vol.29, no. 1, pp. 10-18.</ref> Bandura’s theory indicated a number of sources of self efficacy including: personal accomplishments, vicarious experiences (modelling), verbal persuasion, imaginal experience, physiological states, and emotional states. | <span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> | ||

</span> | |||

<span style="line-height: 1.5em;" /> | |||

• '''Support from parents, teachers and peers - '''Parents and teachers need to hear how much their support matters to their children, even at high school level.<ref name="H12" /> In addition to parental support, peer influences appear to be very important with respect to participation in organised sport.<ref name="H15">KAHL, H.W. and HOBBS, K., 1998. Development of physical activity behaviour among children and adolescents. Paediatrics. vol. 101, pp. 549-554.</ref>Influences of a best friend were more highly associated with PA behaviour than influences of parents. <ref name="H15" />The facebook page should encourage the social aspect of PA and emphasis peer support and participation as well as exercising with groups. | |||

<br>•'''Self-efficacy to be physically active- '''Another strong predictor of PA is self-perception and self-efficacy to be physically active.<ref name="H16">DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SAUNDERS, R. FELTON, G., WARD, D.S., DOWDA, M. and PATE, R.R, 2004. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 628-636.</ref>Bandura’s self-efficacy theory<ref name="H7" /> suggested that confidence in a personal ability to carry out a behaviour, influences adoption of that behaviour. Consequently girls who have high self-efficacy in their capabilities to be physically active will recognise fewer barriers to exercise or be less affected by them, be more likely to perceive the benefits of PA, and be more likely to enjoy it.<ref name="H17">DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SALLIS, J.F., DUNN, A.L. BIRNBAUM, A.S., WELK, G.J., BEDIMO-RUNG, A.L., VOORHEES, C.C. and JOBE, J.B., 2005. Self-management strategies mediate self-efficacy and physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. vol.29, no. 1, pp. 10-18.</ref> Bandura’s theory indicated a number of sources of self efficacy including: personal accomplishments, vicarious experiences (modelling), verbal persuasion, imaginal experience, physiological states, and emotional states. | |||

<br>It is possible to provide some of these sources within the Facebook page to increase self efficacy in adolescent girls. For example performance accomplishments are based on one’s mastery experience, therefore emphasis the use of achievable goal setting. <ref name="H16" />The use of role models is a prime example of vicarious experience. Vescio et al. <ref name="H18">VESCIO, J., WILDE, K. and CROSSWHITE, J.J, 2005. Profiling sport role models to enhance initiatives for adolescent girls in physical education and sport. European Physical Education Review. vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 153-170.</ref> investigated the use of role models to encourage teenage girls to maintain participation in PA. It was implied that using sports role models could enhance interventions to promote PA. They also identified key attributes of the sports role model are: mostly female, under 40 years old, similar sporting background with a combination of essential feminine and masculine qualities. Interesting, adolescent girls often nominated a family member with affinity for sport as their role model. | <br>It is possible to provide some of these sources within the Facebook page to increase self efficacy in adolescent girls. For example performance accomplishments are based on one’s mastery experience, therefore emphasis the use of achievable goal setting. <ref name="H16" />The use of role models is a prime example of vicarious experience. Vescio et al. <ref name="H18">VESCIO, J., WILDE, K. and CROSSWHITE, J.J, 2005. Profiling sport role models to enhance initiatives for adolescent girls in physical education and sport. European Physical Education Review. vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 153-170.</ref> investigated the use of role models to encourage teenage girls to maintain participation in PA. It was implied that using sports role models could enhance interventions to promote PA. They also identified key attributes of the sports role model are: mostly female, under 40 years old, similar sporting background with a combination of essential feminine and masculine qualities. Interesting, adolescent girls often nominated a family member with affinity for sport as their role model. | ||

[[Image:Being-a-healthy-woman-michelle-obama-quote.jpg]] | |||

'''Body image'''<br>Body image is a multidimensional concept that indicates how we see our own body, and how we think, feel and act towards it. <ref name="H3" /> It involves interplay between our body reality and our body ideal. That is what our actual physical characteristics are compared to how we thing our bodies should look. Negative body image arises as a consequence of perceived environmental pressure to conform to cultural-defined body and beauty ideal. <ref name="H19">SHERWOOD, N.E. and JEFFERY, R.W., 2000. The behavioural determinants of exercise: implications for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition. vol. 20, pp. 21-44.</ref> Women are at higher risk of developing a negative body image than men.<ref name="H20">ELGIN, J. and PRITCHARD, M., 2006. Gender differences in disordered eating and its correlates. Eating and Weight Disorders. vol. 11, pp. 96-101.</ref> The mass media seems to be the biggest source of this ideal, promoting an unrealistic and artificial image of female beauty that is impossible for the majority of females.<ref name="H21">LEVINE, M.P. and MURNEN, S.K., 2009. “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not a cause of eating disorders”: a critical review of evidence for a casual link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. vol. 28, pp. 9-42.</ref>Growing numbers of young women risk their health trying to imitate the body images portrayed in the media. The wrong messages can be harmful to mental self-imaging and self-esteem. {{#ev:youtube|F0pwXRQxSYE}}<br> | '''Body image'''<br>Body image is a multidimensional concept that indicates how we see our own body, and how we think, feel and act towards it. <ref name="H3" /> It involves interplay between our body reality and our body ideal. That is what our actual physical characteristics are compared to how we thing our bodies should look. Negative body image arises as a consequence of perceived environmental pressure to conform to cultural-defined body and beauty ideal. <ref name="H19">SHERWOOD, N.E. and JEFFERY, R.W., 2000. The behavioural determinants of exercise: implications for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition. vol. 20, pp. 21-44.</ref> Women are at higher risk of developing a negative body image than men.<ref name="H20">ELGIN, J. and PRITCHARD, M., 2006. Gender differences in disordered eating and its correlates. Eating and Weight Disorders. vol. 11, pp. 96-101.</ref> The mass media seems to be the biggest source of this ideal, promoting an unrealistic and artificial image of female beauty that is impossible for the majority of females.<ref name="H21">LEVINE, M.P. and MURNEN, S.K., 2009. “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not a cause of eating disorders”: a critical review of evidence for a casual link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. vol. 28, pp. 9-42.</ref>Growing numbers of young women risk their health trying to imitate the body images portrayed in the media. The wrong messages can be harmful to mental self-imaging and self-esteem. {{#ev:youtube|F0pwXRQxSYE}}<br> | ||

Revision as of 18:00, 2 November 2013

Original Editor - Iain Berry, Catherine Muir, Carol Newlands, Helen Power, Melanie Reis, John Watt as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors -

Package Aims[edit | edit source]

This wiki resource is designed primarily for physiotherapists who are actively seeking to increase participation in physical activity through the use of social media. While this resource has focused on promoting physical activity in teenage females and has centred on the social networking site ‘Facebook’, it is hoped that the principles highlighted will be of benefit to any health professional or wider body, seeking to promote health and wellbeing, regardless of the targeted demographic or facet of social media adopted.

The wide ranging physical, social and psychological benefits that can be gained from physical activity are well documented, despite this, participation levels in teenage females remain low. This resource specifically aims to address this issue. Conventional methods of promoting the benefits of physical activity appear to be failing this group, therefore it is believed that the emerging growth in social media can be a useful and productive method of engagement with this demographic.

This resource is not designed to be a ‘how-to-guide’ or ‘blueprint’ to expanding social media, it is however designed to make the user aware of some of the numerous issues that revolve around developing social media as an organic and interactive medium to promote health and wellbeing. It is hoped that this resource will act as a useful tool to the user in developing their own individual resource, as a template for potential in-service education and as a constructive part of the users continuing professional development.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

By the end of this resource the user will be able to:

- Justify and critique the need for health promotion and increased physical activity for teenage females.

- Critically evaluate the current guidelines regarding physical activity in young people.

- Analyse participation and physical activity levels in teenage females.

- Critically evaluate social media as a medium by which to engage teenage females.

- Develop a social media resource aimed at promoting physical activity for teenage females.

- Synthesise appropriate information required to create a social media resource for this population.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of this resource relative to its aims.

Current Guidelines[edit | edit source]

In 2011 Start Active, Stay Actice [2] was published in conjunction with the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety; The Scottish Government; Welsh Government; and the Department of Health. This UK wide document presents guidelines on the amount, duration, frequency and manner of physical activity required across various age related demographics to achieve general health benefits.

This report from all four Chief Medical Officers across the UK is aimed at a range of organisations (inclusive of, but not limited to the NHS and local authorities) whose intension is to design services to promote physical activity. The document was formulated for policymakers, professionals and practitioners whose aim is to devise and effectuate policies and measures that employs the promotion of physical activity, sport and exercise in order to achieve health gains.

Start Active, Stay Active [2] highlighted three guidelines specifically aimed at children and young people (5-18 years) irrespective of gender, race or socio-economic background:

1. All children and young people should engage in moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity for at least 60 minutes and up to several hours every day.

2. Vigorous intensity activities, including those that strengthen muscle and bone, should be incorporated at least three days a week.

3. All children and young people should minimise the amount of time spent being sedentary (sitting) for extended periods.

Types of activities recommended by Start Active, Stay Active: [2]

- Unstructured (children)

Indoor or outdoor play, active travel.

- Unstructured (young people)

Social dancing, active travel, household chores, temporary work.

- Structured (children and young people)

Organised, small-sided games with equipment that maximises sucess (large racquets, low nets, big balls etc).

Educational instruction (through teaching and coaching) that promotes skill learning and development.

Sport and dance.

- Muscle strengthening and bone health (children) Activities that require children to lift their body weight or to do work against a resistance.

Jumping and climbing activities, combined with the use of large apparatus and toys, would be categorised as strength promoting exercise.

- Muscle strengthening and bone health (young people)

Resistance -type exercise during high intensity sport, dance, water-based activities or weight (resistance) training in adult-type gyms.

Evidence Base Regarding Current Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Significant evidence, composed of both observational and experimental research, suggests that regular involvement in physical activity among children and young people offers benefits for physical and psychological well-being both in the short and long term. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

With specific reference to the guidelines highlighted by Start Active, Stay Active, [2] greater levels of physical activity have been shown to be associated with more positive health related outcomes in studies which reported improvements in health related measures as a result of exercise based interventions. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Equally, although some health benefits have been reported as a result of only 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity every day, it has been suggested that this should be implemented as a ‘stepping-stone’ towards the optimal level of 60 minutes. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

Physical activity of vigorous intensity has been shown to improve components of health such as cardiorespiratory fitness, bone strength and muscular strength. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title More recent evidence Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title suggests that the optimum amount of physical activity required to improve bone health may be greater than previously understood, Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title this is reflected in the guidelines as an increase from twice to three times per week. The current evidence Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title suggests that extended sedentary behavior is an independent risk factor for reduced health and correlates strongly with obesity/overweight and metabolic dysfunction although the evidence does not offer any specific maximum/minimum recommended periods of sedentary behavior.

Other guidelines specifically addressing physical activity and teenagers include NICE Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title and WHO. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title Equally, specific mention at this point should be made to the The Scottish Allied Health Professions Directors (AHPD) ‘Pledge to Increase Physical Activity in Scotland.’ Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title This pledge, aimed at all allied health professionals, seeks to increase the level of physical activity in Scotland, importantly this pledge specifically makes reference to the use of social media:

“Use social media opportunities to promote the Pledge and physical activity.” Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title

The evidence behind the AHPD ‘Pledge to Increase Physical Activity in Scotland’ Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title is summarised in this YOUTUBE clip:

Carol - Dropout [edit | edit source]

In Scotland, by the time females have reached the age of 18, 40% dropout of all sports activity[4]. It is well documented in the literature that sport dropout rates of teenage girls exceed that of boys the same age[5]. The Scottish Government’s 2020 healthcare vision recognises Scotland’s population is living longer. This demographic change will place an increased strain on healthcare budgets. The vision also recognises the need to focus on prevention. Targeting teenage females to increase their physical activity is a necessary health prevention measure to help ensure the health of the future work force and reducing the demand on the health service[6].

Decreased physical activity has a whirlwind of consequences. Individuals not reaching the current guidelines of prescribed amount and type of weekly physical activity are more prone to coronary heart disease, osteoporosis, type two diabetes, hypertension, obesity, non- specific low back pain as well as an increased prevalence of cancer[4].

Exercise also promotes psychological and social wellbeing. The psychological benefits include increased self-esteem, confidence and body image perception along with decreased stress, depression and anxiety. Developing team-working skills, increased sexual health and academic performance are included in some of the social advantages. Studies have also demonstrated that exercise can reduce the likelihood of teens engaging in anti-social behaviour[4].

Health promotion is a vital component of the role of a physiotherapist . The current system of health promotion of physical wellbeing aimed at teenage girls does not appear to be working. There is a need for new, innovative strategies to decrease this high level of dropout rates and improve the health of such individuals not only for the present but also for the future[6][4].

Alex Neil MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing:

“ Everyone who is involved in the delivery of healthcare in Scotland is asked to play their part in making this vision a reality and to live the values that are shared across Scotland’s Health Service to guide the way they work and decisions they take”[6].

What Can Be Done? [edit | edit source]

In order to target the population of teenage girls, one must recognize the best means of communication to promote physical activity and healthy lifestyle. Many companies and health activists have realized the growth, opportunity, and connections that social media provides around the world and have utilized this as the most efficient means of communication. Social media refers to forms of electronic communication through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content[7]. The varying types of social media can be used to target specific demographics. These can include social networking sites, podcasts, blogs, wikis, forums, and content communities[8]. As of 2012, there are over 2.8 billion social media profiles, representing around half of all Internet users worldwide. Social networking is the fastest-growing active social media behaviour online, increasing from 36% of global Internet users to 59% managing their profile on a monthly basis by the end of 2011. Social networking includes sites such as Facebook, YouTube, twitter, and pinterest. Eighty-nine percent of agencies said they would use Facebook to advertise for their clients in 2012 – either by purchasing ads, creating pages, or other methods of engagement[9].

The YouTube video below provides a brief and accurate depiction of the vast worldwide communication through social media that has become a breakthrough in our generation.

Utilizing these methods of communication to promote an idea, event, lifestyle, or product is presently being undertaken by millions of people around the world. As previously mentioned, the Pledge is a current guideline which ‘calls to action’ AHP’s in the promotion of physical activity in all Health Boards in Scotland; included is the use of social media to promote the Pledge and physical activity[11]. Therefore, physiotherapists have the responsibility and, with this training guide, the ability to effectively reach the target demographic through social networking.

To view the Pledge please click here[11].

Social Networking via Facebook[edit | edit source]

There are many statistics and evidence to suggest a multitude of social media resources may be of benefit to target female teenage girls. For the purpose of this training guide, Facebook will be the resource of choice to connect and communicate. There are many positive attributes and reinforcing evidence to suggest that Facebook will be efficient and effective at reaching this target audience. In the UK, at the beginning of 2013 there was an estimated 33 million accounts for Facebook, which is just under 53% of the UK population. In 2012, it was reported that both Facebook and Twitter have the same gender distribution, being 40% male and 60% female, whereas Pinterest is the most female-dominated site at 79% of its users[12]. Research carried out by the London School of Economics for European Commission in 2010, surveyed 25,000 youth, between the ages of 9 and 16 years from across Europe; in the UK, 88% of the 13 – 16 year olds maintained a social networking profile. More generally, 46% of 13 – 16 year olds used Facebook as their main social network site from the study’s subjects[13].

The probability of adolescents searching for health related information has also been studied. This further supports the effectiveness that a Facebook page will provide. Borzekowski and Rickert (2001) reported that physical activity, fitness, and exercise ranked second among health topics searched for online by youth in a school-based survey[14]. Similarly and more recently, Ettel et al. (2012) revealed that a significant number of students trusted the online infor¬mation, and nearly one-quarter subsequently modified their behavior. This is limited by the inability to determine whether the information was from a legitimate source. “Researching” on the Internet by students often includes sites such as Wikipedia, an online encyclopedia that anyone can edit. It is unreasonable to expect adolescents to delve into peer-reviewed medical literature[15]. A physiotherapist’s Facebook page will be considered a legitimate source, as we maintain clinical governance and evidence-based practice as outlined by CSP.

A systematic review was performed by Lau et al. (2011), which presented evidence supporting positive effects of information and communication technology (ICT) in physical activity interventions for children and adolescents, especially when used with other delivery approaches (i.e. face to face). The review also recognized the explicit need for increased studies and research into the impact and effects of social networking to promote physical activity within children and adolescents, and considerations for longer duration follow ups considering the development of a physically active lifestyle may require up to 6 months[15].

In conclusion, social media, in today’s teenage population, has become apart of life and social networking is researched as the most common form used. Physiotherapists should now be able to understand and provide reason, with this information, as to why using social networking, as a means of connecting and communicating with teenage girls to promote health and physical activity will be effective and efficient.

The type of content to include on the Facebook page [edit | edit source]

It is vital that the information on the Facebook page is appropriate and safe for the target audience. It needs to be an effective intervention to achieve its aim to promote physically active lifestyles. It is also needs to be tailored to its target audience, adolescent girls[16]. The aim of this section is to provide ideas for the type of content that could be included on your page, to aid a successful intervention.

Difficulty with physical activity adherence[edit | edit source]

Regardless of the obvious social, health and personal benefits of regular exercise, mentioned earlier, many people still remain sedentary. People often quote lack of time, energy or motivation as reasons not to be active. Interestingly, these factors are all internal and personally controllable and are amenable to change.[1] Even after sedentary people have been inspired to start exercising, the next barrier they face is continuing their exercise program. Exercise adherence can be difficult for some people for a number of reasons:

• The recommendations are often based on fitness data, ignoring people’s psychological readiness to exercise.

• Most exercise prescriptions are overly restrictive and do not allow for development of self motivation for regular exercise.

• Exercise recommendations are based on rigid principles of intensity, duration and frequency are too challenging for many people especially beginners.

• Traditional exercise prescription does not promote self-responsibility or encourage people to adopt long-term behaviour changes.[1]

In order to enhance the effectiveness of your Facebook page, it is important its content does not reflect these points. Effective interventions are created by employing theory and research based knowledge about the determinants of PA. [17]

Models and Theories of Exercise behaviour [edit | edit source]

There are a number of theoretical models that help us understand the process of PA adoption and adherence. [18]

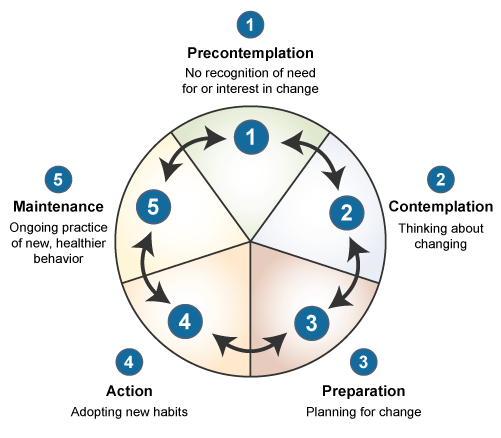

Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

The TTM [19] integrates current behavioural status with a person’s intention to maintain or change their pattern of behaviour. The core of this model is five stages of motivational readiness for change, these are summarised in figure 1. When considering content for your Facebook page, try to include information that is appropriate for people in each of these stages. For those in the precontempation stage for example, provide information regarding the benefits of regular exercise (link to 23.5 hour video), or tips for injury prevention for those in the maintenance stage.

Figure 1: Summary of The Transtheoretical Model

Social Cognitive Theory

Social Cognitive Theory [20] [21]proposes that personal, behavioural, and environmental factors operate as collective interacting determinants. Interventions based on the Social Cognitive Theory focus on the importance of the individual’s ability to control her/his own behaviour and on how changes in the individual, the environment, or in both can produce changes in behaviour.Interventions derived from Social Cognitive Theory utilize techniques such as goal setting, self monitoring (exercise diaries) relapse prevention training, stimulus control strategies (identifying high risk thoughts and feelings) and social support to promote changes in physical activity.

Creating an effective intervention to promote physical activity[edit | edit source]

Interventions do not directly change behaviour, but they act to modify one or more PA determinants, which can result in increased PA. Determinants are factors that relate to PA adherence and can be thought of as falling into two categories: personal and environmental factors. They are not to be considered in isolated variable, but rather, they influence and are influenced by each other as they contribute to behaviour outcomes. [1] Personal factors consist of variables such as self-efficacy, self-motivation, past participation in exercise. [22] Environmental factors include social environment (family and peers), the physical environment (weather, facilities, time) and characteristics of PA (intensity, duration, frequency).[1]

Kahn et al.[23] conducted a review of all PA interventions and they identified the determinants of PA allegedly influenced by interventions. This information was used to classify the interventions as one of the following approaches:

• Informational approaches – aims to change the knowledge and attitude about the benefits of and opportunities for PA

• Behavioural approaches – teaches people the behavioural management skills to adopt and maintain PA

• Social approaches- aims to create a social environment that facilitates and enhances behavioural change

• Environmental and policy approach- targets the structure of physical and organisational environmental to provide safe, attractive and convenient places for PA.

The advantage of the Facebook page is that all of these approaches can be utilised in one intervention, which can influence a large number of determinates at the same time.

Effective content to promote physical activity in adolescent girls[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier it is essential to tailor the intervention to its target audience. To optimise adolescent girl’s participation and adherence to physical activity (PA), it is pointless providing information on your Facebook page that focuses on traditional, strict, boring and unattractive exercise prescription. It is necessary to identify factor that are associated with PA, are amenable to change and can be addressed realistically within the page.

Determinants of PA for adolescent girls

In adolescent girls the most cited determinants of PA were as follows:

• Time constraint- Teenage girls report being “too busy” and having conflicts with other activities which are preventing them from exercising.[24] [25] [26] [27]These findings suggest the importance of helping adolescent learn time management strategies. Include tips on the Facebook page advocating making PA a priority and recommend ways to fit PA into their daily lives i.e. engaging in 3 x 10 minutes of PA spread throughout their day or by keep activity logs.

• Support from parents, teachers and peers - Parents and teachers need to hear how much their support matters to their children, even at high school level.[26] In addition to parental support, peer influences appear to be very important with respect to participation in organised sport.[28]Influences of a best friend were more highly associated with PA behaviour than influences of parents. [28]The facebook page should encourage the social aspect of PA and emphasis peer support and participation as well as exercising with groups.

•Self-efficacy to be physically active- Another strong predictor of PA is self-perception and self-efficacy to be physically active.[29]Bandura’s self-efficacy theory[30] suggested that confidence in a personal ability to carry out a behaviour, influences adoption of that behaviour. Consequently girls who have high self-efficacy in their capabilities to be physically active will recognise fewer barriers to exercise or be less affected by them, be more likely to perceive the benefits of PA, and be more likely to enjoy it.[31] Bandura’s theory indicated a number of sources of self efficacy including: personal accomplishments, vicarious experiences (modelling), verbal persuasion, imaginal experience, physiological states, and emotional states.

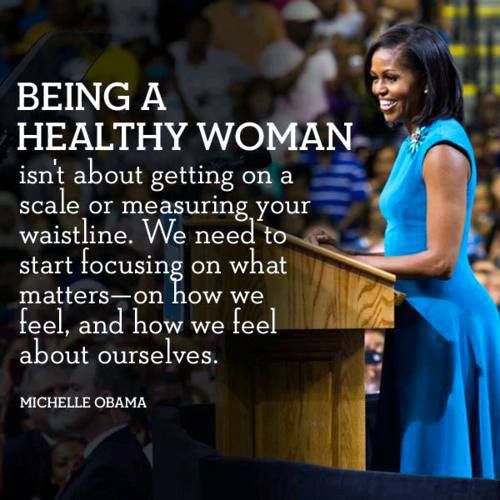

It is possible to provide some of these sources within the Facebook page to increase self efficacy in adolescent girls. For example performance accomplishments are based on one’s mastery experience, therefore emphasis the use of achievable goal setting. [29]The use of role models is a prime example of vicarious experience. Vescio et al. [32] investigated the use of role models to encourage teenage girls to maintain participation in PA. It was implied that using sports role models could enhance interventions to promote PA. They also identified key attributes of the sports role model are: mostly female, under 40 years old, similar sporting background with a combination of essential feminine and masculine qualities. Interesting, adolescent girls often nominated a family member with affinity for sport as their role model.

Body image

Body image is a multidimensional concept that indicates how we see our own body, and how we think, feel and act towards it. [17] It involves interplay between our body reality and our body ideal. That is what our actual physical characteristics are compared to how we thing our bodies should look. Negative body image arises as a consequence of perceived environmental pressure to conform to cultural-defined body and beauty ideal. [33] Women are at higher risk of developing a negative body image than men.[34] The mass media seems to be the biggest source of this ideal, promoting an unrealistic and artificial image of female beauty that is impossible for the majority of females.[35]Growing numbers of young women risk their health trying to imitate the body images portrayed in the media. The wrong messages can be harmful to mental self-imaging and self-esteem.

Exercise has been shown to improve body image among both men and women.[36] A combination of both aerobic and resistance training is more affective than aerobic alone. For the facebook page, there are several things to keep in mind when promoting exercise to improve body image. Firstly, when promoting exercise it is important to show a wide variety of body sizes, shapes and fitness levels. [17]. Showing super-fit models send the message that a fit appearance is a requirement for exercising particularly in gyms. Secondly, the aim of the page should be to promote improving physical function, strength and endurance rather than on changing physical appearance. Efforts should be made to help girls set realistic and attainable goals. Finally, it is granted that many girls will start exercising to improve their body image, but the page should be directed towards educating them about the other physical and mental benefits of exercise.

Summary of the do’s and don’ts[edit | edit source]

Do’s

• Promote healthy lifestyle changes

• Providing cues for exercise motivation (pictures, memes and videos)

• Make exercise enjoyable and purposeful

• Tailor information to the target audience.

• Include information for all stages of motivational readiness for change

• Promote exercise with friends

• Advice on time management skills

• Offer a choice of activities

• Find convenient, safe and suitable places to exercise

• Encourage self setting of SMART goals

• Promote support from family and peers

• Suggest keeping daily exercise logs

• Use realistic role models

• show a wide variety of body sizes, shapes and fitness levels

Don’ts

• Focus on weight loss and body image

• Use pictures of ultra-fit women with idealistic body types

• Promote unrealistic workout programmes

• Use difficult scientific language

In summary in order to ensure your Facebook page is a successful intervention to promote PA in adolescent girls, it is necessary to use evidenced based models and theories as a framework to understand the process of exercise adoption and adherence. Also the information provided on the page should focus on key determinant of PA that is targeted toward adolescent girls. Efforts should be made to suggest gaining support from significant others, address real and perceived time constraints, and help adolescent girls feel better about themselves in general and more specifically about their PA skills.

Items to consider when constructing a social media resource[edit | edit source]

The CSP (Chartered Society of Physiotherapy) provides a document called Social Media Guidance[37], and should be referred to, to highlight the legal, regulatory and professional perspectives of using and creating a social media page as a professional. Specific guidance include legal, regulatory and professional consideration.

Legal considerations

- Maintaining privacy and confidentiality when uploading and sharing information

- Awareness to defamation; consider what you are writing and communicating

- Alert to harassment, including racist, sexist or homophobic comments

Regulatory considerations

The HPC has no specific guidance on the use of social media but as registrants, the Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics are equally applicable to social media use:

- Act in the best interests of service users

- Respect confidentiality of service users

- Keep high standards of personal conduct

- Behave honestly and with integrity, making sure that your behavior does not damage the public’s confidence in you and your profession

Professional considerations

- CSP code

o Ensure confidential information acquired remains secure

o Recognize potential impacts of personal behavior, life-style and activity

o Recognize their role as advocates of physiotherapy

- Maintaining clear professional boundaries

o Maintain high security settings on personal accounts

o Establish clear boundaries with users

• Do not respond to requests from users via your personal account

• Do not friend request current or former users

• Ensure professional communications at all times

- Consent

o Gaining appropriate consent when using images, video clips and information

o Giving clear information on how users information will be used[37]

Working with adolescents and children[edit | edit source]

As some users may be under the legal age of 18, it is important to have knowledge and an understanding of relevant trust and

local authority policies relating to the care of children. When suggesting activities and groups on a social media page, items of safety, child protection and consent must be considered. Such considerations as, appropriate training and criminal record checks, verified for those individuals or organization involved with children[38].

Being aware of child safety policies will fulfill the requirements of the CSP, HCP and UK law to support the delivery of consistent high quality standards of care for children and their families[39].

Other considerations

Consider inclusive programs and activities that consider religion, culture, ethnic background, sexual orientation, gender-identity, physical and mental ability.

Be aware and able to address potential cyberbullying

Helpful links:

Guidance on helping keep children and young people safe online – NSPCC

http://www.safenetwork.org.uk/help_and_advice/Pages/safety_online.aspx

Social media guidance – CSP

http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/social-media-guidance

2007 Information to guide good practice for physiotherapists working with children – ACPC

http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/physiotherapists-working-children

Creating a Facebook Page - A step by step guide[edit | edit source]

Facebook users have to register and create a personal profile, after which they can connect or “become friends” with other users, exchange messages and become members of groups or followers of pages. Based on a survey of 4,000 physicians, 61 % of them use Facebook for personal; and 15 % of them use it for professional purposes. Moreover, 33 % of physicians have received friend requests from their patients on Facebook and only 75 % of them declined the request [40]. Therefore, it may be useful to create a separate professional profile before creating any page or group.

The purpose of a Facebook Group is to provide a place for small group communication and for people to share their common interests and express their opinion [41]. Conversely, Facebook Pages are useful for businesses, organisations and brands to share their stories and connect with people. Pages can be customised by adding apps, posting stories, hosting events and more. People who like your Page and their friends will get updates in News Feed. You cancreate and manage a Facebook Pagefrom your professional account. Below is a guide on how to achieve this

How to Create a New Facebook Page[edit | edit source]

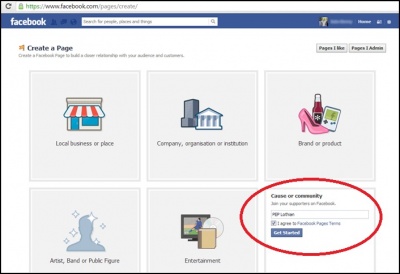

In creating a Facebook Page you need to first decide on a topic or idea to centre the page around. For the purposes of this resource we have decided to focus on health provision in teenage girls in the Midlothian region of Scotland.

Once you have decided on the topic, you can then create the page on Facebook by following these steps:

1. Log in to your Facebook account and click on the ‘create a Page’ option in the sidebar. If this option is not available, enter ‘create a Page’ into the search box and it will take you directly to the screen.

2. Take a look at the main categories of the Pages and decide which one fits your resource. Click on one of the boxes to select that main category for your resource and browse through the categories in the drop-down menus to see which one fits best (we found the community option best suited our needs).

3. Enter the name of your resource and select the box next to “I agree to Facebook Pages Terms”. You will be able to change your Page name up until the point you have 200 fans (or likes), so if you aren’t sure about the name at the start, you can tweak it for a little while.

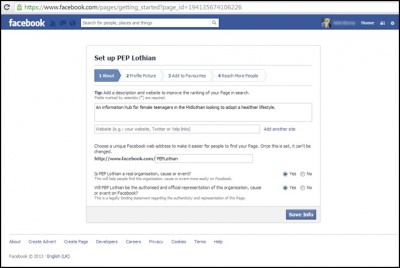

4. Add your basic ‘about’ information. This information will appear on your page just below your cover photo. It should be noted that the ‘about’ page will be indexed in Google therefore it useful to ensure it is very descriptive and contains relevant keywords. There is also the option to link to a website if you have one at this stage. You may want to direct people to other relevant sites to such Twitter or other social media sites.

5. Add your profile picture. This image will appear next to every post that goes into the news feed from your Page so should be recognisable and associated to your resource (such as a logo).

6. Finally you have the option to advertise your page in order to reach a wider audience (if there are finances available to do so). This option can be skipped if it is not relevant to you.

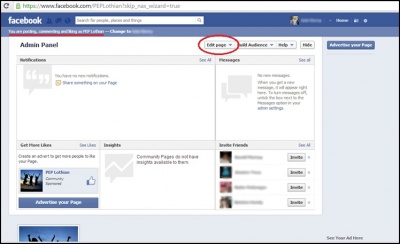

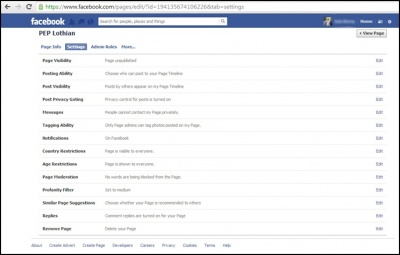

7. Following this you will now have a completed Facebook Page and you will be directed to the pages admin panel. From here you receive updates about your page in a summarised form and, perhaps more importantly at this stage, can access the settings section to edit your privacy and security options.

8. By clicking on ‘edit page’ and then ‘edit settings’ you will have the options to protect your page as you see fit. It may be useful to initially ‘unpublish’ your page in order to familiarise yourself with the page and make any alterations whilst it is not able to be viewed to the public. When the page is ready it can then ‘published’ again. By carefully considering each option in this section you can ensure control of: who can post (posting ability), who can see the page (country/ age restrictions) as well as control over what is being said on your news feed (page moderation/ profanity filter).

==

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 WEINBURGH, R.S. and GOULD, D., 2007. Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. 4th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, HEALTH IMPROVEMENT AND PROTECTION., 2011. Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries' Chief Medical Officers. July.

- ↑ CSP., (2013). Public Health [Online]. [Viewed October 8 2013]. Available from http://www.csp.org.uk/topics/public-health

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 SPORTS SCOTLAND., (2013). Making women and Girls more Active a GoodPractice Guide [Online]. [Viewed 7 October 2013]. Available from http://www.scottishstudentsport.com/assets/downloads/making-women-and-girls-more-active.pdf

- ↑ WOMEN’S SPORT AND FITNESS FOUNDATION., (2008). Teenage Girls and Dropout [Online}. [Viewed October 8 2013]. Available from http://www.wsff.org.uk/system/1/assets/files/000/000/275/275/bde5b8839/original/Teenage_girls_and_dropout.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 NHS SCOTLAND., (2013). A Route Map to the 2020 Vision for Health and Social Care [Online]. [Viewed 7 October 2013]. Available from http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0042/00423188.pdf

- ↑ Merrian-Webster., 2013. Social Media [online]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.jmir.org/2011/3/e48/.

- ↑ Mayfield, A., 2008. What is Social Media [online]. California: Creative Commons [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.icrossing.co.uk/fileadmin/uploads/eBooks/What_is_Social_Media_iCrossing_ebook.pdf.

- ↑ Pring, S., 2012. 100 more social media statistics for 2012 [online]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.agentmedia.co.uk/social-media/100-more-social-media-statistics-for-2012/.

- ↑ PAUL ALLEN MEDIA., 2012. Social media UK statistics [online video]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IO1Qi5swY-Q.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 NHS Health Scotland., 2009. AHP Directors physical activity pledge [online]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.paha.org.uk/Announcement/ahp-directors-physical-activity-pledge.

- ↑ Pingdom., 2012. Report: social network demographics in 2012 [online]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://royal.pingdom.com/2012/08/21/report-social-network-demographics-in-2012/.

- ↑ BBC., 2011. Many under 13’s ‘using Facebook’ [online]. [viewed 20 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-13129150.

- ↑ BORZEKOWSKI, D. and RICKERT, V., 2001. Adolescent cybersurfing for health information: A new resource that crosses barriers. Archive of Paediatric Adolescent Medicine. July, vol. 155, pp. 813-817.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 ETTEL, G., NATHANSON, I., ETTEL, D., WILSON, C. and MEOLA, P. 2012. How do adolescents access health information? And do they ask their physicians? The Permanente Journal. Vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 35-38. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Mel 8" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ MARCUS, B.H., OWEN, O., FORSYTH, L.A.H., CAVILL, N.A. and FRIDINGER, F., 1998. Physical activity interventions using mass media, print media and information technology. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 362-378.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 LOX, C.L., MARTIN GINIS, K.A. and PETRUZZELLO, S.J., 2010. The psychology of exercise: integrating theory and practice. 3rd ed. Scottsdale, Arizona: Holcomb Hathaway Publishers.

- ↑ CULOS-REED, S.M., GYURCSIK, C. and BRAWLET, L.R., 2001. Using theories of motivated behaviour to understand physical activity. In: R. SINGER, 2 ed. Handbook of sports psychology. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ PROCHASKA, J.O., DICLEMENTE, C.C. and NORCROSS, J.C., 1992. In search of how people change. American Psychologist. vol. 47, pp. 1102-1114.

- ↑ BANDURA, A., 1986. Social foundations of thought and actions: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentic Hill.

- ↑ BANDURA, A., 1997. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

- ↑ SHERWOOD, N.E. and JEFFERY, R.W., 2000. The behavioural determinants of exercise: implications for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition. vol. 20, pp. 21-44.

- ↑ KAHN, E.B., RAMSEY, L.T., BROWNSON, R.C., HEATH, G.W., HOWZE, E.H., POWELL, K.E., STONE, E.J., RAJAB, M.W., CORSO, P. and The Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2002. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. vol. 22, pp. 73-107.

- ↑ ALLISON, K.R., DWYER, J.J.M. and MAKIN, S., 1999. Perceived barriers to physical activity among high school students. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 608-615.

- ↑ SALLIS, J.F., PROCHASKA, J. J. and TAYLOR, C., 1999. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 963-975.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 NEUMARK-SZTAINER, D., STORY, M., HANNAN, P..J., THARP, T. and REX, J., 2003. Factors associated with changes in physical activity: a cohort study of inactive adolescent girls. Arch Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine. vol. 157, pp. 803-810.

- ↑ ROBBINS, L.B. and KAZANIS, A.S., 2003. Barriers to physical activity perceived by adolescent girls. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 206-212.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 KAHL, H.W. and HOBBS, K., 1998. Development of physical activity behaviour among children and adolescents. Paediatrics. vol. 101, pp. 549-554.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SAUNDERS, R. FELTON, G., WARD, D.S., DOWDA, M. and PATE, R.R, 2004. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school-based physical-activity intervention among adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine. vol. 28, pp. 628-636.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedH7 - ↑ DISHMAN, R.K., MOTL, R.W., SALLIS, J.F., DUNN, A.L. BIRNBAUM, A.S., WELK, G.J., BEDIMO-RUNG, A.L., VOORHEES, C.C. and JOBE, J.B., 2005. Self-management strategies mediate self-efficacy and physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. vol.29, no. 1, pp. 10-18.

- ↑ VESCIO, J., WILDE, K. and CROSSWHITE, J.J, 2005. Profiling sport role models to enhance initiatives for adolescent girls in physical education and sport. European Physical Education Review. vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 153-170.

- ↑ SHERWOOD, N.E. and JEFFERY, R.W., 2000. The behavioural determinants of exercise: implications for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition. vol. 20, pp. 21-44.

- ↑ ELGIN, J. and PRITCHARD, M., 2006. Gender differences in disordered eating and its correlates. Eating and Weight Disorders. vol. 11, pp. 96-101.

- ↑ LEVINE, M.P. and MURNEN, S.K., 2009. “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not a cause of eating disorders”: a critical review of evidence for a casual link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. vol. 28, pp. 9-42.

- ↑ CAMPBELL, A. and HAUSEBLAS, H.A., 2013. Effect of exercise interventions on body image: a meta-analysis. Journal of Health Psychology. vol 14, no.6, pp.780-793.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 THE CHARTERED SOCIETY OF PHYSIOTHERAPY (CSP). 2012. Social Media Guidance [online]. [viewed 22 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk

- ↑ NATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO CHILDREN (NSPCC). 2013. Safe Network. [online]. [viewed 22 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.safenetwork.org.uk

- ↑ THE CHARTERED SOCIETY OF PHYSIOTHERAPY (CSP). 2007. 2007 Information to guide good practice for physiotherapists working with children [online]. [viewed 22 October 2013]. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk

- ↑ MESKO, B., 2013. Social Media in Clinical Practice [online]. London: Springer [viewed 11 October 2013]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4471-4306-2/page/1

- ↑ PINEDA, N., 2010. Facebook Tips: What’s the Difference between a Facebook Page and Group? [online]. [viewed 18 October 2013]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook/facebook-tips-whats-the-difference-between-a-facebook-page-and-group/324706977130