Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP)

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Lead Editors

Definition

[edit | edit source]

Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP) is one of three classifications of Intensive care -unit acquired weakness (ICUAW), the others being Critical Illness Myopathy (CIM) and Critical Illness Neuromyopathy (CINM)[1]. ICUAW is defined as 'a clinically detected weakness in critically ill patients in whom there is no plausable aetiology other than critical illness' [2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

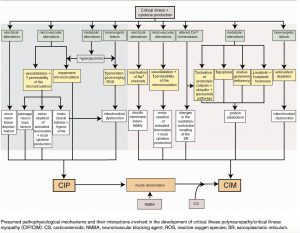

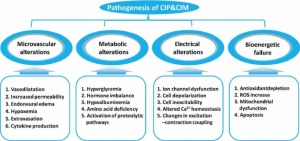

The pathophysiology for CIP remains unclear and complex, with human studies highlighting axonal degeneration [3].It has been thought that the mechanism may involve:

- Microvascular alterations: Increase in E- Selectin expression, vasodilation, increased capillary permeability, extravasation and endoneural oedema which results in hypoxia.

- Metabolic alterations: Production of toxic factors such as cytokines, hyperglycaemia, hormone imbalance, hypoalbuminemia, amina acid deficiency and activation of proteolytic pathways.

- Electrical alterations: Ion channel dysfunction, cell depolarisation, inexcitability, altered calcium homeostasis and changes in excitation-contraction coupling.

- Bionenergetic failure: Anti-oxident depletion, an increase in reactive oxygen species, mitochrondial dysfunction and apoptosis.

Risk Factors

- Sepsis

- SIRS

- Multi Organ Failure (MOF)

- Female Gender

- Duration of Organ Dysfunction

- Duration of ICU Stay

- Ionotropic Support

- Renal Failure

- Low Serum Albumin

- Hyperglycemia

- Neuromuscular Blockades

- Corticosteroids

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Visser (2006) [4] reports that the clinical features of CIP typically include:

- Muscle Weakness: Predominantly in the lower extremities. This should be suspected if there is reduced limb movement following a painful stimulus to the distal limb. Flaccid weakness can be observed symmetrically.

- Absent Facial Weakness: Cranial nerves are rarely affected.

- Muscle Wasting: Observed in one third of patients

- Reduced Muscle Reflexes: Reflexes are usually present at the start of the disease, but decrease over time.

- Difficulty in Weaning from Ventillator

- Sensory Loss: Although difficult to assess with a sedated or intubated patient.

- Impaired Consciousness: Suggested of an encephalopathy is also usually present

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Medical Research Council (MRC)[edit | edit source]

Also known as the Oxford Muscle Grading System, the MRC is a measurement of muscle strength ranging from 0 (no contraction at all) to 5 (normal). To assist with the diagnosis of CIP, bi-lateral testing of shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, wrist extension, hip flexion, knee extension, and dorsiflexion of the ankle will create a total score of 60[5]. 48/60 designates ICUAW or significant weakness, and an MRC score below 36/48 indicates severe weakness[6]

Electrophysiological testing[edit | edit source]

This includes both nerve conduction studies and electromyography examination, however these resources are limited at a number of ICU's. Typically, nerve conduction studies highlight a reduced compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and in some instances the sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) may be reduced. Nerve conduction velocity is usually normal or minimally reduced[7].

BIOMARKERS[edit | edit source]

Currently there are no validated biomarkers available, creatine kinase and plasma levels of neurofilaments (a marker of axonal injury) are elevated in those with ICUAW, however the former not being a particular reliable biomarker[8][9] as they are normal when muscle necrosis is absent or scattered which, with CIP, is commonly the case[10].

Biopsy[edit | edit source]

Although not commonly performed, CIP will demonstrate features of denervation and reinnervation with small muscle fibers, fiber-type grouping, and fiber group atrophy with widespread axonal degeneration of both motor and sensory nerves. Muscle biopsy can display thick filament loss which is commonly associated with CIM, with evidence of denervation and reinnervation changes and axonal degeneration associated with CIP

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Muscle Strength Testing (MRC)

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to management approaches to the condition

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Guillain-barre syndrome (GBS)[edit | edit source]

GBS is an autoimmune disease of the peripheral nervous system that is typically progressive and symmetric with ascending paralysis, sensory abnormalities and areflexia, with 30% of patients requiring mechanical support [11].

Never conduction tests highlights decreased velocity in GBS whereas normal conduction velocity and decreased action potentials. The stand out difference between CIP and GBS is that CIP is a part of critical illness that typically occurs during an intensive care stay, whereas GBS leads to an intensive care admission [3].

trauma[edit | edit source]

A spinal cord or head injury should be ruled should there be muscle weakness following a traumatic injury, as spinal shock can result in muscle weakness and areflexia [4]

neuromuscular blockades[edit | edit source]

Prolonged neuromuscular blockades can result in the development of acute quadriplegic myopathy, and can be identified by repetitive nerve stimulation. This can be reversed by giving cholinesterase inhibitors. Sensation and reflexes are usually spared [4]

CRITICAL ILLNESS MYOPATHY (CIM)[edit | edit source]

Resources

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Appleton, R. and Kinsella, J., 2012. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain, 12(2), pp.62-66.

- ↑ Stevens, R.D., Marshall, S.A., Cornblath, D.R., Hoke, A., Needham, D.M., de Jonghe, B., Ali, N.A. and Sharshar, T., 2009. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Critical care medicine, 37(10), pp.S299-S308.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zhou, C., Wu, L., Ni, F., Ji, W., Wu, J. and Zhang, H., 2014. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a systematic review. Neural regeneration research, 9(1), p.101.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Visser, L.H., 2006. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: clinical features, risk factors and prognosis. European journal of neurology, 13(11), pp.1203-1212.

- ↑ Hermans, G. and Van den Berghe, G., 2015. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Critical care, 19(1), p.274.

- ↑ Latronico, N. and Gosselink, R., 2015. A guided approach to diagnose severe muscle weakness in the intensive care unit. Revista Brasileira de terapia intensiva, 27(3), pp.199-201.

- ↑ Latronico, N. and Bolton, C.F., 2011. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a major cause of muscle weakness and paralysis. The Lancet Neurology, 10(10), pp.931-941.

- ↑ De Jonghe, B., Sharshar, T., Lefaucheur, J.P., Authier, F.J., Durand-Zaleski, I., Boussarsar, M., Cerf, C., Renaud, E., Mesrati, F., Carlet, J. and Raphaël, J.C., 2002. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. Jama, 288(22), pp.2859-2867.

- ↑ Wieske, L., Witteveen, E., Petzold, A., Verhamme, C., Schultz, M.J., van Schaik, I.N. and Horn, J., 2014. Neurofilaments as a plasma biomarker for ICU-acquired weakness: an observational pilot study. Critical Care, 18(1), p.R18.

- ↑ Hermans, G., De Jonghe, B., Bruyninckx, F. and Van den Berghe, G., 2008. Clinical review: critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy. Critical care, 12(6), p.238.

- ↑ Rooney, K.A. and Thomas, N.J., 2010. Severe pulmonary hypertension associated with the acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 11(1), pp.e16-e19.