Craig's Test

Top Contributors - Manisha Shrestha, Kim Jackson and Stacy Schiurring

Purpose[edit | edit source]

Craig's test is a passive test that is used to measure femoral anteversion or forward torsion of the femoral neck. It is also known as 'Trochanteric Prominence Angle Test (TPAT)'.[1]

Femoral anteversion is the angle between the femoral neck and femoral shaft, indicating the degree of torsion of the femur. It is also known as Femoral neck anteversion.[2][1]

There are various ways via which femoral anteversion can be measured. These are some methods used: imaging using radiography, fluoroscopy, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as functional assessments.[1] Craig's test is the most commonly used physical examination test for femoral anteversion.[3]

Technique[edit | edit source]

Patient position[edit | edit source]

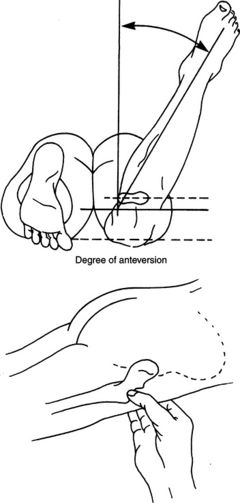

The patient was placed in the prone position with hip in neutral and the knee flexion of 90° of tested side on an examination table.[3]

Therapist position[edit | edit source]

The examiner stands toward the posterolateral aspect of the tested side.

Procedure[edit | edit source]

Examiner then palpated the greater trochanter of the tested side while passively internally rotating the hip until the most prominent portion of the greater trochanter reached its most lateral position.[3][4]

One examiner hold the position of leg in the position where greater trochanter is the most prominent. Another examiner measures the angle between the shaft of the tibia (a line bisecting the medial and lateral malleoli) and a line perpendicular to the table (an imaginary vertical line extending from the table) using either goniometer or inclinometer. And thus records the angle of femoral anteversion.[3][4]

Interpretation[edit | edit source]

- Normal: At birth, the mean anteversion angle is 30 degrees which decreases to 8-15 degrees in adults (angle of internal rotation).

- Angle >15 degrees: Increased anteversion leads to squinting patellae & pigeon toed walking (in-toeing) which is twice as common in girls.

- Angle <8 degrees: Retroversion[5]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Pyschometric Properties[edit | edit source]

Clinical Significance[edit | edit source]

- it decreases during the growing period. At birth, the mean angle is approximately 30°; in the adult, the mean angle is 8° to 15°. Increased anteversion leads to squinting patellae and toeing-in. Excessive anteversion is twice as common in girls as in boys. A common clinical finding of excessive anteversion is excessive medial hip rotation (more than 60°) and decreased lateral rotation in extension.

Gelberman et al. pointed out, however, that rotation should be viewed both in neutral (as in Craig’s test) and with 90° of hip flexion because rotation shows greater variability in flexion. They felt that greater medial rotation than lateral rotation in both positions was a better indicator of increased femoral anteversion.

- Femoral internal and external rotation can be measured via the digital goniometer by 2 different methods as follows: in the supine position with 90° of hip and knee flexion and in the prone position with hip extension and 90° of knee flexion.

- Femoral Anteversion Angle (FAA) can also be tested with help of Computer Tomographic images was defined as a crossing angle between a line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the center of the base of the femoral neck and a line connecting the exact posterior aspects of the lateral and medial condyles.

- There are various lower extremity alignment variables. Out of which femoral anteversion has been identified as a risk factor for hip and knee joint injury. Increased femoral anteversion can increase hip adduction and knee abduction because the patella shifts to the medial side of the femoral condyle groove, thereby increasing the Q-angle and ultimately resulting in knee valgus deformity. So, an accurate assessment of femoral anteversion is important for diagnosing and preventing hip and knee injuries, and Craig's test helps to measure femoral anteversion.[2]

Resources[edit | edit source]

add any relevant resources here

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Scorcelletti M, Reeves ND, Rittweger J, Ireland A. Femoral anteversion: significance and measurement. Journal of Anatomy. 2020 Nov;237(5):811-26.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Choi BR, Kang SY. Intra-and inter-examiner reliability of goniometer and inclinometer use in Craig’s test. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(4):1141-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ito I, Miura K, Kimura Y, Sasaki E, Tsuda E, Ishibashi Y. Differences between the Craig’s test and computed tomography in measuring femoral anteversion in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2020;32(6):365-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Choi BR, Kang SY. Intra-and inter-examiner reliability of goniometer and inclinometer use in Craig’s test. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(4):1141-4.

- ↑ Epomedicine [Internet]. Clinical Skills and Approches. Femoral Anteversion test (Craig’s test). [updated 2020 Jun 27; cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from: https://epomedicine.com/clinical-medicine/femoral-anteversion-craigs-test/

- ↑ Clinical Physio. Craig's Test for Hip | Clinical Physio Premium. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qi41LYsVy1E