Cluster Headaches

Original Editors - Len Coughlin from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

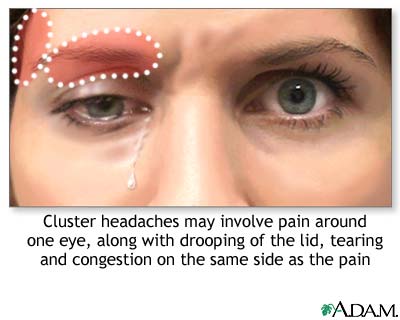

Cluster headaches are the rarest but the most painful of the primary headaches.[1] Cluster headaches are the most common of trigeminal autonomic cephalaligias (TACs). Primary headaches are caused by spontaneous activation of nociceptive pathways and also include migraines or tension-type headaches.[2] Cluster headaches are characterized by recurring short lasting attacks (15 to 180 minutes). The attacks typically consist of exruciating unilateral periorbital or temporal pain as well as at least one ipsilateral autonomic symptoms. Accompanying ipsilateral symptoms include conjunctival injection and lacrimation, nasal congestion or rhinorrhea, forehead and facial sweating, facial flushing, eyelid edema, miosis and ptosis.[2][3]

There are two types of cluster headaches, episodic and chronic. Episodic is defined by periods of susceptibility to headache known as cluster periods, that alternate with periods of remission.[1] The headache can occur for 1 to 3 months (the cluster period) where patients experience ≥ 1 attack/day, followed by remission for months to years.[1][3] The headache can then reoccur in the same pattern. Around 80% of of all cases are episodic cluster headaches.[1][2] Around 20% of all cases are chronic cluster headaches. Chronic is defined by the cluster periods occuring for one year or more, without more than one month of remission or the remission lasts less than 14 days.[2][1] Chronic cluster headaches are preceded by episodic cluster headaches and develop overtime.[1]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Cluster headaches (CHs) are reported as affecting either 1% to 4%[1] of the population with 0.4%[3] prevalence in the population of the US. Other sources have the prevalence at 0.5 - 1 out of 1,000 people.[2] One study reported 2.73% of patients in a tertiary care headache clinic being diagnosed with cluster headaches.[2] CHs are diagnosed most commonly in men between the ages of 20 to 50 and onset of the condition typically occurs in the third decade.[1][2] African American males have a higher incidence of CHs than other racial backgrounds and increased recognition of the disease in women is causing the ratio of men to women with CHs to decrease.[2] Children are rarely diagnosed with CHs and symptoms often decrease after the age of 70 years old.[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- severe headache - localized to one eye and the frontotemporal region. Pain is boring and nonthrobbing

- temporal artery bulging and pulsating

- unilateral ptosis, swelling, and redness of eyelid

- miosis, conjunctival injection

- tearing

- nasal congestion, rhinorrhea

- flushing of side of the face, sweating[1][2][3]

Attacks usually occur at the same time each day, often when a patient wakes up from an afternoon nap or sleep during the night.[3] CHs follow a circadian rhythm and cluster periods occur during the same time each year. They occur most commonly after the shortest or longest days of the year.[1]

Pain is described typically in the area of the first trigeminal branch and almost always on the same side of the head. CH is described as one of the most painful conditions known to man and female patients say the pain is worse than giving birth.[2] Patients compare the sensation to a red hot needle or nail being driven into their eye, or their eyeball being ripped from its socket. Suicidal ideas or feelings are somtimes expressed because of the severity of the pain and CHs are sometimes referred to as "suicide headaches." Pain increases suddenly and remains incredibly intense for 15 to 180 minutes until it suddenly subsides.[1][2]

Physical activity seems to alleviate pain during a CH so patients often prefer standing or sitting erect over lying down or reclining. During the cluster period, patients are restless and may rock from side to side, hit their heads, hit objects with their fists or even hit their head against a wall. This behavior is so typical that it is accepted as a criterion in the International Classification of Headaches Diseases (ICHD-II).[2]

| [5] | [6] |

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

- sleep apnea

- hypoxemia

- anxiety

- compulsiveness

- hypochondria

- stroke

- hypertension

- diabetes

- asthma

- obesity

- fibromyalgia

- low back pain

- depression

- cardiovascular diseases[1][7]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Preventitive

- verapamil, lithium, topiramate, divalproex[3], methysergide, verapamil combined with prednisone[1]

Aborting Attacks

- parenteral triptans, dihydroergotamine, 100% O2 inhalation given by nonbreathing facemask[3], sumatriptan, ergotamine[1], intransal topical lidocaine [2]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of cluster headache is based on whether symptoms meet clinical criteria and exclusion of a secondary cause. Obtaining a detailed clinical history is very important because of the lack of ability of diagnostic tests to confirm a patient has CHs.[2]

Diagnostic criteria for cluster headache according to the International Classification of Headache Diseases II[2]

3.1 Cluster headache

A. At least five attacks fulfilling B through D

B. Severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain lasting 15 to 180 minutes if untreated

C. Headache is accompanied by at least one of the following:

1. Ipsilateral conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation

2. Ipsilateral nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea

3. Ipsilateral eyelid edema

4. Ipsilateral forehead and facial sweating

5. Ipsilateral miosis and/or ptosis

6. A sense of restlessness or agitation

D. Attacks have a frequency from one every other day to eight per day

E. Not attributed to another disorder

In order to differentiate between episodic and chronic CHs another set of diagnostic criteria is used.

ICHD-II criteria for episodic and chronic cluster headache[2]

Episodic cluster headache

A. All fulfilling criteria A through E of 3.1

B. At least two cluster periods lasting from 7 to 365 days and separated by pain free remissions of > 1 month.

Chronic cluster headache

A. All fulfilling criteria A through E of 3.1

B. Attacks recur for > 1 year without remission periods or with remission periods lasting < 1 month.

Any patient with a refractory (unmanageable) case should undergo an MRI to exlude any treatable cause. The pituitary, orbit, and trigeminal pathway have to be specifically examined with a CT Scan and MRI.[2]

Causes[edit | edit source]

The exact cause of CH is unknown, but it appears to have multifaceted components and dysfunction at many levels. The neurovascular aspect is evident by the effects of vasoactive substances on CHs. Vasodilators trigger CH attacks and vasoconstrictors end them.[2] Vasodilation of the opthalmic and internal carotid arteries occurs ipsilateral to the pain.[1] It is unclear whether activiation of the trigeminal vascular system is a cause or consequence of CH. The stimulation of the trigeminal comlex causes a cerebral vasodilator response. The cerebrospinal fluid changes in a way that indicates autonomic (parasympathetic and sympathetic) and central nervous system involvement in CH.[1]

The periodic patterns of CH have directed studies toward the hypothalamus which controls the circadian rhythms. PET studies show an activation of the posterior hypothalamus during CH attacks.[2] The CH period is also characterized by disturbances of neuroendocrine substances (prolactin, testosterone, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and cortisol) based on circadian rhythms. Decreased testosterone and alteration of hormone and melatonin production occurs during the cluster period. Platelet levels of histamine and serotonin increase during the episode of headache and decrease when the headache is over. Mast cells, the major source of histamine in many tissues, are found in increased number in the skin of the painful temporal area in cluster headache patients. This is particularly evident within the first 10 hours after a cluster attack.[8] Blood pressure increases, heart rate decreases during a cluster period. This may indicate an involvement of the carotid body because of the impact its receptor has on blood pressure and heart rate.[1]

Leroux and Ducros state that "the parasympathetic component of the autonomic symptoms is thought to be mediated by the trigeminal-autonomic reflex in the brainstem circuitry,via the seventh cranial nerve. The sympathetic innervation pathway to the pupil and eyelid is composed of three neurons and there is no clear demonstration of the site involved and mechanisms underlying the dysfunction in CH."[1]

There is no unified hypothesis that adequately explains all of the clinical occurences associated with cluster headaches.

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Trigeminal complex is main source of involvement. Due to possible causes and comorbidities the central nervous system and cardiovascular system are involved with CH.

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

A very useful article regarding management of CH can be found at American Academy of Family Physicians Online. It is linked HERE and at the bottom of the page under case reports.

Education involving triggers for the patient's CH is very important. To help identify triggers, a headache journal is very useful. Once patients begin to understand the triggers of their CH, they can attempt to avoid the precipitating factors leading up to a CH.[1]

ClusterHeadaches.com.au, Drugs.com, Goodman, and Merck.com present identical strategies for the treatement of a CH. All report that treatment for a cluster headaches involves two approaches:

Your doctor may recommend the following treatments for when the headaches occurs:

- Triptans, such as sumatriptan (Imitrex)

- Several weeks of anti-inflammatory (steroid) medicines such as prednisone -- starting with a high dose, then gradually decreased

- Injections of the drug known as dihydroergotamine (DHE), which can stop cluster attacks within 5 minute (Warning: this drug can be dangerous if taken with sumatriptan) [9]

- The inhalation of 100 percent oxygen, via a tight-fitting mask at a flow rate of 8 to 10 liters/min for 10 to 15 minutes is dramatically effective for about 80 percent of those patients for whom this approach is feasible; oxygen is particularly effective for nocturnal attacks. Oxygen inhalation can be repeated up to 5 time a day. Studies have shown significant cerebral vasoconstriction with inhalation of 100% oxygen during a cluster headache. Oxygen also increases the synthesis of serotonin by the CNS.[8]

A combination of medicines may be needed to control headache symptoms. Because each person responds differently to medicine, your doctor may have you try several medications before deciding which works best for you.

Painkillers do not usually relieve the pain from cluster headaches. Generally, they take too long to work. [8]

The following medications may also be used to treat or prevent headache symptoms:

- Antiseizure medications such as topiramate and valproic acid

- Indomethacin or naproxen

- Lithium carbonate

- Calcium channel blockers such as verapamil

- Propranolol

- Amitriptyline

- Cyproheptadine [9]

Invasive Procedures

For patients who show no response to medial management several surgical procedures have been implemented. Surgeries directed toward the sensory trigeminal nerve have shown the most success. Hypothalamic implants have been used in patients with chronic CH.[1] Specific surgeries include percutaneous glycerol injections into the trigeminal cistern, trigeminal sensory rhizotomy, percutaneous radiofrequency trigeminal rhizotomy, superficial petrosal neurectomy, trigeminal branch avulsion, and decompression of the nervus intermedius.[8]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

The preferred practice pattern for CHs is 5D: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System-Acquired in Adolescence or Adulthood. Goodman states that "the use of thermal and EMG biofeedback may be of benefit."[1] Educating patients on common triggers of CH and things to avoid is important for the PT. Instruction about precipitating factors which include alcohol, abrubpt changes in sleeping patterns due to travel, and work shift changs is important. Other precipating factors include lack of sleep, naps, burst of anger, prolonged anxiety, or altitude hypemia during flights. Also since physical activity seems to alleviate pain in CH patients, aggressive exercise can help improve symptoms.[1]

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

There are a wide variety of alternative management techniques that can be found, all of which have little validity based on research. However, some do offer promising results and should be considered when dealing with cluster headaches due to the debilitating nature of the condition.

Sutton and Herbert report that "a retrospective analysis found that LSD and psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”) not only interrupted cluster headaches, but blocked successive headaches in the cluster in 53 patients.14 These drugs were also shown to increase the remission period between cycles, a key efficacy characteristic."[11] The long term efffects of this type of therapy is relatively unknown and the use of illegal drugs often appears negative to the patients.

Patients with severe snoring and cluster headache should be evaluated for sleep apnea. In some patients diagnosed with sleep apnea, treatment for apnea also proved to be effective for the headaches.[12]

Botulinum toxins A and B are being studied as treatments for various headaches, with evidence of some efficacy and mixed reports as to side effects. An ongoing study is addressing their role in chronic cluster headache.[12]

A recent report described a patient with intractable cluster headache; PET scanning revealed activation of the posterior inferior hypothalamic gray matter during attacks. A stereotactic electrode was implanted in this area, with a permanent generator placed in a subclavicular pocket. When stimulation was provided at a frequency of 180 Hz, the attacks disappeared after 48 hours. Twice, the stimulator was turned off without the patient’s knowledge, and attacks returned within 48 hours. The latter attacks disappeared 48 hours after the generator was restarted. Thirteen months later, the pain had not recurred.[12]

Other alternative treatments mentioned in articles included acupuncture, point stimulation, and dietary changes.

The major theme with any treatment is that if the patient is willing and it results in relief from cluster headaches then it might be worth taking a look into.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- migraine

- tension-type headache

- other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

- temporal arteritis

- trigeminal neuralgia

- chronic paroxysmal hemicrania

- hemicrania continua

- pericarotid syndrome/ Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome

- sinusitis

- glaucoma[1][2]

One of the more important characteristics of CHs to remember when ruling out other diagnoses is that CHs follow a pattern. They occur at generally the same time of day and same time of year and pain is typically always on the same side of the face.[1]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

- LSD for the Treatment of Cluster Headaches

- Management of Cluster Headache

- Hypothalamic Stimulation Offers Relief for Cluster Headache

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1xMHPfv-Z-B7f9Sd9j1zSufpYfBA-mmDuPfFR6110Ywipe-Ycr|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 Goodman Catherine C., Fuller Kenda S. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2009. p1559-1561

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 Leroux E, Ducros A. Cluster headache. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2008; 3:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-20. http://ukpmc.ac.uk/articlerender.cgi?tool=pubmed&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;pubmedid=18651939 (Accessed 2 March 2010).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Silberstein, Stephen D. Cluster Headache. Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec16/ch216/ch216b.html?qt=Cluster%20Headaches&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;alt=sh (Accessed 2 March 2010).

- ↑ Chuck. Cluster Headache Attack. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzpcPeoPnW0 [last accessed 4/5/10]

- ↑ artonio7. Cluster Headache. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LAf_QFmTPkw [last accessed 4/5/10]

- ↑ AtLastTheCatsBack. Cluster Headaches: My POV on Exruciating Pain! Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCb_BPBh5dQ [last accessed 4/5/10]

- ↑ Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. The Lancet Neurology April 2008;7(4):354-361. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&amp;amp;amp;_udi=B6X3F-4S1CYX9-F&amp;amp;amp;_user=134779&amp;amp;amp;_coverDate=04%2F30%2F2008&amp;amp;amp;_rdoc=1&amp;amp;amp;_fmt=high&amp;amp;amp;_orig=search&amp;amp;amp;_sort=d&amp;amp;amp;_docanchor=&amp;amp;amp;view=c&amp;amp;amp;_searchStrId=1237461465&amp;amp;amp;_rerunOrigin=google&amp;amp;amp;_acct=C000011238&amp;amp;amp;_version=1&amp;amp;amp;_urlVersion=0&amp;amp;amp;_userid=134779&amp;amp;amp;md5=0f44f307c7b2d98b693a1866f9b95f73#secx9 (accessed 4 March 2010).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 ClusterHeadaches.com.au. Full Medical Information. Available from: http://www.clusterheadaches.com.au/full_medical.php#TREATMENT. {last accessed 4/5/10]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Drugs.com: Drug Information Online. Cluster Headaches. Available from: http://www.drugs.com/enc/cluster-headache.html. [last accessed 4/5/10] Retrieved from "http://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php5?title=Cluster_Headaches" Category: Bellarmine Student Project

- ↑ healthandlongevity. Oxygen Therapy Alleviates Cluster Headache Pain. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WAF_YT6PaCI[last accessed 4/5/10]

- ↑ Sutton J, Herbert N. LSD for the Treatment of Cluster Headaches: Risk Report. Clusterbusters.com. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:qGGR_ehqIb0J:www.clusterbusters.com/riskreport.doc+%22cluster+headaches%22+and+%22case+reports%22&cd=7&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us. (Accessed 4/11/10)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Beck E, Sieber W, Trejo R. Management of Cluster Headache. American Family Physician February 2005. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0215/p717.html. (accessed 11 April 2010).