Auscultation

| Image:Stop_hand.gif

|

Please do not edit this page unless you are part of the RCSI student project. |

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Auscultation of the heart is an integral part of physical examination of a patient. Blood flowing across the heart valves is laminar flow so that no sound is produced. The sounds heard on auscultation are the sound of the valve cusps snapping shut at the end of diastole (when the AV valves shut producing the 1st heart sound) and at the end of systole (when the Aortic & Pulmonary valves shut producing the 2nd heart sound).

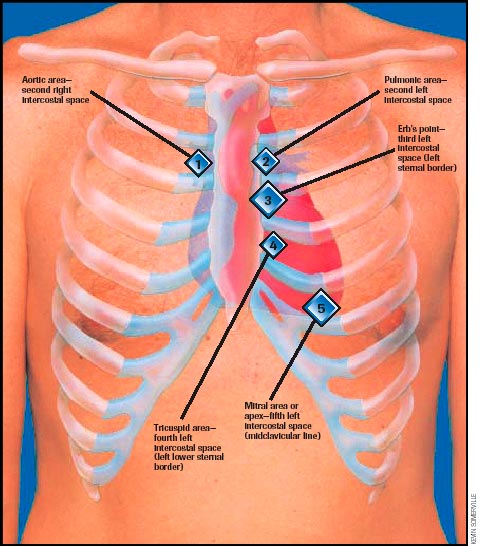

These sounds are conducted to the surface of the body and can be heard with the aid of a stethoscope. There are specific places on the anterior chest wall where the sound from each of the 4 valves can best be heard. These are not the surface markings of the valves but rather the points where the sounds are best conducted to. They are as follows:

• Aortic Valve – R 2nd ICS

• Pulmonary Valve – L 2nd ICS

• Tricuspid Valve – L sternal border

• Mitral Valve – 5th ICS MCL

The stethoscope comprises a bell and a diaphragm. The bell is designed to hear low pitched sounds and the diaphragm is designed to hear high pitched sounds. They are connected via rubber tubing to the ear pieces. These should be worn facing forward as the ear canals run anteriorly.

Techniques:[edit | edit source]

Auscultation is a vital part of any physical examination, where it is used in both cardiovascular and respiratory exam. It is routinely used, and can provide strong evidence in including or excluding different pathological conditions that are manifested clinically in the patient.

It should be noted that auscultation comes after palpation, where the patient is lying comfortably at 45 degrees angle with his chest region fully exposed. There are four main regions of interest for auscultation, and a brief knowledge in human anatomy is crucial to pinpoint them.

The 4 percordial areas are examined with diaphragm, including:

1. Aortic region (between the 2nd and 3rd intercostal spaces at the right sternal border) (RUSB – right upper sternal border).

2. Pulmonic region (between the 2nd and 3rd intercostal spaces at the left sternal border) (LUSB – left upper sternal border).

3. Tricuspid region (between the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th intercostal spaces at the left sternal border) (LLSB – left lower sternal border).

4. Mitral region (near the apex of the heard between the 5th and 6th intercostal spaces in the mid-clavicular line) (apex of the heart)1.

The stethoscope has a diaghram and a bell. The bell is most effective at transmitting lower frequency sounds, while the diaphragm is most effective at transmitting higher frequency sounds2.

The four pericardial areas relate to the heart sounds and can detect various abnormalities in the heart such as the valve stenosis or incompetence which are diagnostic for many diseases in the cardiovascular system. However, there are specific manoeuvres done for further investigation, and some of these would include3:

For Respiratory examination, the patient would be sitting at the end of the bed, where in auscultation of the posterior chest you would;

1. Auscultate from side to side and top to bottom. Omit the areas covered by the scapulae.

2. Compare one side to the other looking for asymmetry.

3. Note the location and quality of the sounds you hear.

Technique

Ask the patient to disrobe, as this will allow the stethoscope to be placed directly on the chest.

Make sure the patient is sits upright in a relaxed position, where this is possible.

You should then instruct the patient to breathe a little deeper than normal through the mouth.

The bell/diaphragm of the stethoscope is then placed against the chest wall.

Auscultation of the lungs should be systematic, including all lobes of the anterior, lateral and posterior chest.

The examiner should begin at the bottom, compare side with side and work towards the lung apices.

The examiner should listen to at least one ventilatory cycle at each position of the chest wall.

The examiner should identify four characteristics of breath sounds.

These are the pitch, amplitude, then distinctive characteristics and the duration of the inspiratory sound compared with the expiratory sound.

Other Considerations4:

The surrounding has to have the following as to optimize the effectiveness of auscultation.

1) Quiet - the ambient noise might interfere the heart and lung sounds.

2) Warm - so that the patient feels comfortable while the upper part of the body is being exposed. Also, it is to avoid shivering that may add the noise.

3) Appropriate lighting - to allow good coordination between visual and auscultory findings.

Lung Sounds:[edit | edit source]

Normal breath sounds are usually quite, mostly inspiratory, with a distinctive pause before a quiter expiratory phase.

The main breathing abnormalities are:

• Crackles

• Wheezes

• Pleural Rub

Crackles:

Crackles (rales) are caused by excessive fluid in the airways. It is caused by either an exudate or a transduate. Exduate is due to lung infection e.g pneumonia while transduate such as congestive heart failure.[1] A crackle occurs when a small airways pop’s open during inspiration after collapsing due to fluid or lack of aeration during expiration. [2] Crackles are much more common in inspiratory than in expiratory.

Crackles are high-pitched and discontinuous. They sound like hair being rubbed together. [3] There are three different types; fine, medium and coarse.

• Fine are typically late inspiratory and coarse are usually early inspiratory

• Fine crackles are high pitched, very brief and soft. It sounds like rolling a strand of hair between two fingers. Fine crackles could suggest an interstitial process; e.g pulmonary fibrosis, congestive heart failure.

• Coarse crackles are louder, more low pitched and longer lasting. They sound like the separation of Velcro. Coarse crackles could suggest an airway disease, chronic bronchitis. [4]

Wheezes:

Wheezes are an expiratory sound caused by forced airflow through collapsed airways. Due to the collapsed or abnormally narrow airway, the velocity of air in the lungs is elevated. [1] Wheezes are continuous high pitched hissing sounds. They are heard more frequently on expiration than on inspiration. If they are monophonic it us due to an obstruction in one airway only but if they are polyphonic than the cause is a more general obstruction of airways. [5] Where the wheeze occurs in the respiratory cycle depends on the obstructions location, [6] if wheezing occurs in the expiratory phase of respiration it is usually connected to broncholiar disease. [7] If the wheezing is in the inspiratory phase, it is an indicator of stiff stenosis whose causes range from tumours to scarring. One of the main causes of wheezing is asthma, [7] other causes could be pulmonary edema, interstitial lung disease and chronic bronchitis.

Pleural Rub:

Pleural Rub produces a creaking or brushing sound. These occur when the pleural surfaces are inflamed and as a result rub against one another. They are heard during both inspiratory and expiratory phases of the lung cycle and can be both continuous and discontinuous. Pleural rub can suggest pneumothorax or pleural effusion.

.

Sounds: Sounds like: Caused by: Could be cause of:

Scattered Wet Crackles typically inspiratory

particularly wet sounding Excessive Fluid Within the Lungs Pneumonia

Other lung infections

Crackles Hair being rubbed together or Velcro opening

They are discontinuous, non-musical and brief Small airways open during inspiration and collapse during expiration

ARDS

asthma

bronchiectasis

chronic bronchitis

consolidation

early CHF

interstitial lung disease

pulmonary edema

Wheezes Usually heard on expiration. continuous,

high pitched, hissing sounds forced airflow through abnormally collapsed airways with residual trapping of air Asthma

CHF

chronic bronchitis

COPD

pulmonary edema

Pleural Rub creaking or brushing sounds. Can be continuous or discontinuous pleural surfaces are inflamed or roughened and rub against each other pleural effusion

pneumothorax

Heart Sounds:[edit | edit source]

Heart sounds and implications of these sounds

1) Normal heart sounds:

These consist of two sharp sounds, S1 and S2, which diffreciate systole from diastole and no other significant sounds will be heard. A systole occurs when the ventricles fill with blood and the heart contracts. The sudden closure of the tricuspid valves and AV valves is caused by a decrease in pressure in the atria and a sharp increase in the intraventricular pressure which exceeds the pressure of the atria. This is the S1 sound. The ventricles continue to contract throughout systole forcing blood through the aortic and pulmonary semilunar valves. S2 is formed at the end of systole when the ventricles begin to relax and the pressure in the aorta and pulmonary artery begin to exceed the intraventricular pressure. When this happens there is a slight backflow of blood into the heart which causes the semilunar valves to snap shut, producing S2. These two sounds are to be considered single and instantaneous, indicating a normal healthy heart.

2) Aortic Stenosis:

This is a systolic murmur that indicates a physiological defect. The word stenosis refers to the abnormal turbulent flow of blood due to a narrow damaged blood vessel. Stenosis in the aorta results in this murmur sound which occurs between S1 and S2. In addition to this other sounds may be heard such as S4 which results from the heavy work required by the left ventricle to pump the blood though the stenotic valve. Also because S2 is caused by the sudden closing of the aortic valve ,a weaken poorly functioning stenotic valve may cause S2 to be very discreet or even inaudible. This murmur is usually best heard over the aortic area.it is important to note that this is a sharp murmur with notable start and finishing points within a systole. We can usually tell how serious the stenosis is by listening to the timing of the murmur. An early peaking murmur is usually a less serious case of stenosis , while a late peaking murmur indicates more serious stenosis, because the stenotic valve is quite weak and the ventricle takes a lot more time to build the strength to pump the blood out of the heart.

3) Mitral valve prolapse:

This sound is thought to e caused by the failure of the papillary muscles and/or chordae to maintain tension during the late systole. As the left ventricle decreases in size the papillary muscles and/or the chordae don’t tether the valve resulting in the mitral valve remaining slightly open and a slight regurgitation period into the atium. The sound is formed during systole just when the valve prolapses and consists of a mid-systolic click just after a normal S1 sound. This sound alone is enough for diagnosis, however MVP is often followed by a murmur best heard at the apex of the heart. In addition to this ,it can be enhanced or decreased by certain maneuvers. Standing the patient up will decrease the volume of the left ventricle and cause the MVP to occur more frequently. If the patients squats the opposite effect is seen ,the ventricle volume is increased and more tension is put on the papillary muscles and chordae which help close the valve. This condition is common in young adult women and causes symptoms of light-headednesss, anxiety and palpitation attacks. Symptoms are usually mild but patients with evidence of the MVP should be given antibiotic prophylaxis when undergoing any invasive procedures to help avoid the risk of bacterial endocarditis.

4) Pulmonary Stenosis:

This is similar to aortic stenosis in that it takes longer for the right ventricle to pump the blood out of the heart through the stenotic pulmonary valve. This results in a delay in the valve closing and causes a split in S2. This splitting of S2 is heard because the aortic valve shuts before the stenotic pulmonary valve at the end of the systole. T he splitting is best heard in the pulmonic area, the second intercostal space along the left sternal border. Maneuvers such as a heavy inspiration can increase the intensity of this murmur.

File:C:\Documents and Settings\Student\My Documents\Semester 2\Module 12\Physiopedia project

Pictures/ Diagrams[edit | edit source]

References:[edit | edit source]

(1) http://www.med.ucla.edu/wilkes/intro.html

(2) http://filer.case.edu/dck3/heart/listen.html

(3) http://medinfo.ufl.edu/year1/bcs/clist/resp.html

(4) http://www.nurse411.com/Heart_Lung_Sounds.asp

[1] Auscultation Assistant

[2] RL Wilkins, JR Dexter and JR Smith (1984). "Survey of adventitious lung sound terminology in case reports". Chest 85: 523–525. doi:10.1378/chest.85.4.523. http://chestjournal.org/cgi/content/abstract/85/4/523

[3] Lung and Infectious Diseases RL Wilkins, JR Dexter and JR Smith (1984). "Survey of adventitious lung sound terminology in case reports". Chest 85: 523–525. doi:10.1378/chest.85.4.523. http://chestjournal.org/cgi/content/abstract/85/4/523

[4] Forgacs P (1978). "The functional basis of pulmonary sounds" (PDF). Chest 73 (3): 399–405. doi:10.1378/chest.73.3.399. PMID 630938. http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/reprint/73/3/399.

[5] http://sprojects.mmi.mcgill.ca/mvs/RESP01.HTM#abnormalsounds

[6] ^ Shim CS, Williams MH (May 1983). "Relationship of wheezing to the severity of obstruction in asthma". Arch Intern Med. 143 (5): 890–2. doi:10.1001/archinte.143.5.890. PMID 6679232.

[7] ^ Baughman RP, Loudon RG (Nov 1984). "Quantitation of wheezing in acute asthma" ([dead link] – Scholar search). Chest 86 (5): 718–22. doi:10.1378/chest.86.5.718. PMID 6488909. http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=6488909.