Assessment and Management of Cervicogenic Headaches Post Traumatic Injury

Definition description[edit | edit source]

A cervicogenic headache (CGH) is a chronic headache that presents as unilateral pain starting at the neck and is perceived in one or more regions of the head/face (Khalili, et al., 2022) (see more about cervicogenic headaches here).

A common cause of CGH is trauma that has led to dysfunction of the neck. Types of trauma that can cause CGH most commonly include: whiplash caused by car accident, contact sport injuries causing concussion or neck injury, and falls leading to upper cervical structural damage (Page, 2011).

Mechanisms of injury caused by these types of trauma may include structural damage, development of myofascial pain and interaction of the trigeminal nociceptive system with the occipital nerves. There are also emotional and psychological factors to consider post-trauma which can impact rehabilitation and healing outcomes (Packard, 2002).

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Studies focused solely on CGH post trauma is limited. Current research states:

· Prevalent in 30 to 44 year-olds

· Accounts for 1-4% of headaches

· Equally prevalent between males and females

· Onset is said to be early 30s and diagnosis is 49.4 years-old (due to seeking medical attention late)

· Compared to other headache patients, CGH have pericranial muscle tenderness on the painful side (Khalili, et al., 2022)

Relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

The cervical spine is made up of 7 vertebrae (C1 to C7), cranial nerves (C1 to C8), muscles and ligaments (see cervical anatomy)

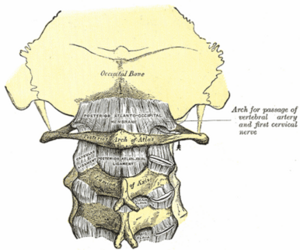

Joints[edit | edit source]

· C1 (atlas) supports the skull and articulates superiorly with the occiput to form the atlanto-occipital joint. This allows for 33% of flexion and extension at the C-spine

· C2 (axis) articulates with the atlas to form the atlantoaxial joint. Its main function is to provide 60% of cervical rotation

· C3-C7 are similar to one another and make up the rest of the movement in the C-spine (Keiser, et al., 2021)

Muscles innervated by C1-C3[edit | edit source]

· Rectus capitis and lateralis

· Longus capitis

· Prevertebral muscle

· Sternocleidomastoid

· Levator scapulae

· Upper trapezius

· Scalenus Medius (Keiser, et al., 2021)

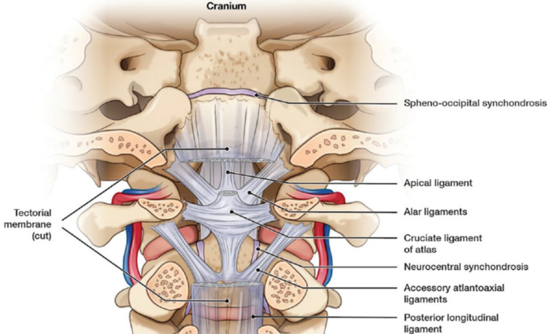

Ligaments (C1-C3)[edit | edit source]

· Apical

· Alar

· Cruciform

· Anterior/posterior longitudinal

· Ligamentum flavum

· Interspinous

· Nuchal

· Transverse (Keiser, et al., 2021)

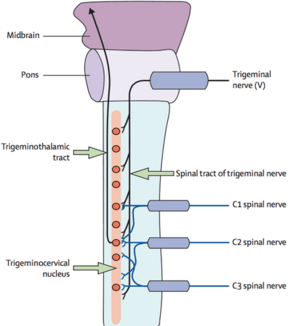

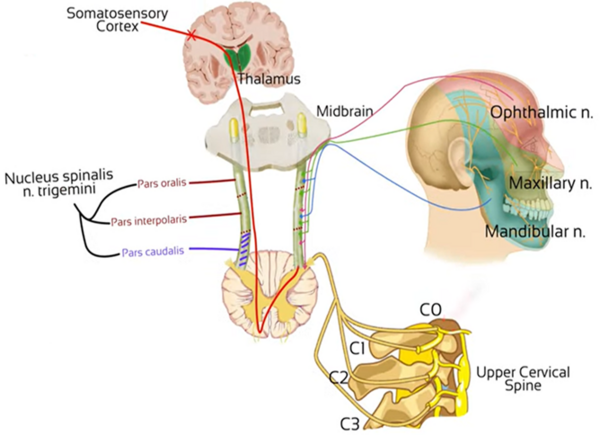

Trigeminocervical nucleus[edit | edit source]

· Located at the lower brainstem near the upper cervical spine

· Vertical cluster of cell bodies in the medullary region

· Within this area a convergence of the trigeminal sensory nerves and the C1 - C3 spinal nerves occurs

· Sensory nerve fibers in the descending tract of the trigeminal nerve are believed to interact with sensory fibres from the upper cervical roots

· Converged information then passed on to the somatosensory cortex (Chua, et al., 2012)

Etiology[edit | edit source]

A CGH is believed to be pain referring from dysfunction of cervical structures innervated by cervical nerves C1, C2 and C3. Meaning, trauma causing damage to joints, intervertebral discs, ligaments and muscles can all be a source of a CGH. There is limited evidence to suggest that the lower cervical spine plays a role in referred pain causing a CGH.

The most common cause of CGH have been attributed to whiplash injury. It is believed that this type of injury accounts for up to 53% of all CGH, with 15.2% of patients having a headache lasting longer 42 days and 4.6% developing chronic daily headaches (Ludvigsson, et al., 2019). Research also suggests that around 50% of CGH originate from the C2-C3 zygapophysial joint (Becker, 2010).

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Activation of the trigeminal nerve and its connections are well established in regards to headaches. In terms of post-traumatic CGH, activation occurs from disruption of structures innervated by spinal nerves C1-C3.

Efferent innervation converges onto the second order neuron at the dorsal horn of C1/C2. At the same time, the trigeminal nerve will send sensory information from the face. The trigeminal nerve converges in the second order neuron in the at the same spinal segment as C1/C2. This sensory information will be sent to the trigeminocervical nucleus within the brainstem. When afferent nociception stimulus from the upper cervical structures travel to the trigeminocervical nucleus, the information sent to the somatosensory cortex becomes corrupt. This is due to the higher number of nociceptive efferent nerves in the face compared to the upper cervical spine. The convergence within the trigeminocervical nucleus means the brain will process this as an error, as it will assume the pain originates from the area with the higher area of nociceptive innervation. As a result, pain originating from the upper C-spine will be referred to the head and present as a CGH. Lower pain thresholds caused by emotional changes and aseptic inflammation can increase CGH pain levels further (Blumenfeld & Siavoshi, 2018).

Management: A multi-disciplinary approach [edit | edit source]

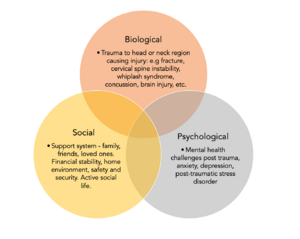

The evidence suggests a multi- disciplinary biopsychosocial model in order to effectively treat and manage post-traumatic cervicogenic headaches. (1). Post-traumatic cervicogenic headaches are multi-dimensional and often part of the larger persistent post-traumatic symptom picture.

Mental Health:[edit | edit source]

Clinical psychologists and neuro psychologically are key members of the multidisciplinary team when treating post traumatic cervicogenic headaches. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are tragically common post traumatic injuries. (3) This is vital to consider when planning a treatment model for a patient post-traumatic injury to the head and/or neck. Depression and anxiety have been proven to continue to increase negative symptoms and worsened prognosis in headache disorders. Mental health challenges paired with ongoing pain are linked with poor sleep quality, deficient nutrient, decreased exercises, pain catastrophising post trauma, emotional distress and post-traumatic stress disorder are linked with persistent post-traumatic cervicogenic symptoms (4).

In alignment with a holistic management approach, cognitive behavioural therapy has been suggested to aid with post-traumatic cervicogenic symptoms and the burden it carries. A journal from Brain Injury, by Gurr & Coetzer explore the effectiveness of CBT for post traumatic headaches. This study hones into the importance of psychological factors presenting as highly influential in increasing or decreasing pain. In this study, Forty-five participants attended the Brain Injury Service for initial three weekly relaxation group sessions. Following this, participants received 6 fortnightly 30 minute individual therapy sessions with one follow up. Interventions included: progressive muscle relaxation combined with imager, psycho-education, cognitive-behavioural strategies, life management, maintenance and relapse prevention. The findings present with over half participants of the brain therapy programme reporting significant decrease oh headache symptoms and disability of function, as well as intensity, frequency per month and pain levels. Although the inclusion criteria does not specify cervicogenic headaches within the population’s diagnosis, the mechanism of injury of a cervicogenic headache discussed is synonymous with post-traumatic headache: a new onset of head and neck pain following a traumatic injury (road traffic accident, sporting injury, fall).

Graded Exposure to Exercise :[edit | edit source]

Patients post traumatic head or neck injury experience fear over inducing headache and/or pain upon physical activity, which leads to significantly increased disability, socially, mentally and physically (5). Moreover, subthreshold exercise has been found to be of significant benefit in recovering not just from acute concussion but also persistent post-concussion symptom

EDIT*** Body of literature stating aerobic exercise dimishines the burden of a headache with the proposed mechanisms of upregulation of brain-derived neurotropic factor BDNF, improved neurovascular regulation and modulation of pain EDIT**

Pharmacological:[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Management:[edit | edit source]

Conflicting evidence remains for the efficacy of physiotherapy management post traumatic CGHs. In accordance with the biopsychosocial model of post traumatic CGH (figure X), patient education with detailed explanation of the condition; support of normal movement; avoiding immobilisation; resumption of work and targeted physiotherapy have been suggested (6). An update on the management of post traumatic headache concluded intense physiotherapy is not superior to standard therapy with simple patient education, hence cannot be recommended when considering cost-benefit ratios (6). The managing injuries of neck trial (MINT) (7) investigated the effects of ‘standard treatment’, including simple treatment of symptoms and brief information about the condition was compared to an active treatment and detailed information given in a Whiplash information booklet. Patients were able to report back after 3 weeks if showing unsatisfactory symptom improvement and randomised into a group of 6 physical therapy sessions including manual therapy, soft tissue techniques, endurance training and behavioural techniques, or one physical therapy session with a refresh of advice. The groups showed no significant difference in the primary outcome, neck disability index (NDI).

PROMSIE study (8) compared extensive physical therapy including tailored exercise programmes over 12 weeks (cervical spine exercises; posture re-education; sensorimotor exercise; manual therapy) to advice given in booklet form, with minimally assisted exercises in a 30-minute session. No treatment effect was observed after 12 weeks.

Contradictory evidence shows patients randomised to additional manual therapy techniques (including temporomandibular region) experienced statistically significant decrease in headache intensity at 3 and 6 months when compared to usual care of just manual therapy for cervical spine region (9). A further study with patients experiencing CGHs and cervical trigger points underwent manual therapy techniques or simulated manual therapy. The treatment group experienced increased cervical range of motion and greater reduction in headache intensity (10).

To summarise, more conclusive evidence with larger sample sizes is required to make better judgement about the efficacy and significance of physical therapy interventions in the management of CGHs post trauma.