Adherence to NICE guidelines for lower back pain: Difference between revisions

(Created page with " == '''Introduction''' == Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition which can affect people of all ages. It is the “leading cause of activity limitation and work absence t...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

== '''Audit and Evaluation Results''' == | == '''Audit and Evaluation Results''' == | ||

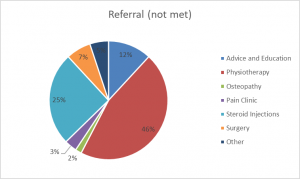

[[File:Referral not met.png|alt=Figure 1.3 distribution of participants who have not previously met the recommendations of NICE Guidelines and areas to which they were referred.|thumb]] | |||

---- | ---- | ||

Revision as of 13:42, 25 May 2018

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition which can affect people of all ages. It is the “leading cause of activity limitation and work absence throughout much of the world” (Duthey, 2013. P.4). In the UK alone over 100 million work days are lost due to LBP and it is identified as being the most common cause of disability in adults, particularly of working age between 40-60 years old (Duthey, 2013). This inflicts a high “economic burden on individuals, families, communities, industry and governments” (Duthey, 2013. P.4).

The cost of LBP on the UK economy is currently estimated to be approximately £12 billion per year (NICE, 2016). In addition, the prevalence of LBP creates increased demand and high costs for the NHS, estimated at approximately £12.3 billion per annum (Whitehurst et al, 2011). With an ageing population this figure is only set to increase, creating an additional strain and financial burden on an already overstretched NHS service.

Generally, most cases of acute LBP recover within 4 to 6 weeks, with most back pain episodes resolved within primary care management (Maher et al. 2017; NICE, 2016). Guidelines are in place to aid primary care providers in managing this population. In the UK these guidelines are produced by NICE (2016), and are a recommended standard of care for LBP in England and Wales (NICE, 2013). They are for use by all primary care clinicians consulting service users suffering from LBP.

NICE (2016) Recommendations For The Management of LBP[edit | edit source]

Primary guidelines recommend a treatment package of, exercise, advice and education, and if necessary the inclusion of manual and psychological therapies (NICE, 2016). Type of exercise may vary depending upon patient needs, preferences and capabilities (NICE, 2016). Guidelines reflect the evidence for a biopsychosocial treatment approach, whereby physical, psychological and social dysfunction determine patient outcome (Kamper, Apeldoorn, Chiarotto et al. 2014). Upon initial assessment a risk stratification, such as the Keele STarT Back Screening Tool should be performed [refer to 8.6], imaging should not be routinely offered (NICE, 2016).

Non-pharmacological interventions[edit | edit source]

Self-management 1.2.1 Provide people with advice and information, tailored to their needs and capabilities, to help them self-manage their low back pain with or without sciatica, at all steps of the treatment pathway. Include: information on the nature of low back pain and sciatica encouragement to continue with normal activities.

Exercise 1.2.2 Consider a group exercise programme (biomechanical, aerobic, mind–body or a combination of approaches) within the NHS for people with a specific episode or flare-up of low back pain with or without sciatica. Take people's specific needs, preferences and capabilities into account when choosing the type of exercise.

Manual therapies 1.2.6 Do not offer traction for managing low back pain with or without sciatica. 1.2.7 Consider manual therapy (spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage) for managing low back pain with or without sciatica, but only as part of a treatment package including exercise, with or without psychological therapy.

Psychological therapy 1.2.13 Consider psychological therapies using a cognitive behavioural approach for managing low back pain with or without sciatica but only as part of a treatment package including exercise, with or without manual therapy (spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage). Combined physical and psychological programmes 1.2.14 Consider a combined physical and psychological programme, incorporating a cognitive behavioural approach (preferably in a group context that takes into account a person's specific needs and capabilities), for people with persistent low back pain or sciatica: when they have significant psychosocial obstacles to recovery (for example, avoiding normal activities based on inappropriate beliefs about their condition) or when previous treatments have not been effective.

Adherence as an Outcome Measure[edit | edit source]

Based on published research and clinical reasoning the outcome measure for adherence was established. For patients to have met the guidelines they must have received three or more NHS physiotherapy treatment sessions, with the inclusion of exercise as part of the treatment plan. Patients who did not meet these standards was classified as receiving non-adherent care.

This number was determined by evaluating the number of exercise sessions other studies had reported when investigating the effects of exercise on LBP. The majority of studies reported in number of weeks rather than number of exercise sessions and this was generally between 8-12 weeks (Geneen et al, 2017., Lizier et al, 2012., Middelkoop et al, 2010., Henchoz et al, 2008., Rainville et al, 2004). RM and AE agreed that this would equate to approximately four physiotherapy sessions and that this would be a fair length of time for treatment to be deemed successful or not. However, this was changed to three or more sessions due to how the SE data was coded during data analysis.

The difficulties of this was that individual studies used varying type, intensity, duration and frequency of exercise therapy, producing variations for number of sessions (Geneen et al. 2017). One could argue, that 1-2 sessions of exercise lead therapy would be inadequate to produce a positive change. However, due to limited resources and NHS funding more than six sessions would not be currently feasible. There remains no evidence which suggests the optimal dosage of exercise or number of treatment sessions to produce the best outcomes for LBP patients. Establishing standards to classify adherent care, therefore remains difficult.

NHS Structure[edit | edit source]

The NHS structure is currently divided into Primary Care and secondary care. Primary Care physicians act as “gatekeepers” and are generally responsible for defining who requires Secondary Care (Akbari et al, 2008., Berendsen et al, 2009). GP’s refer to specialists in SC for a variety of reasons, including; a second opinion, specialist procedures or advice on diagnosis and management if all PC resources have been exhausted (Akbari et al, 2008).

However the referral system is not always effective, whilst some patients may not receive the specialist care they need, many are being referred unnecessarily (Berendsen et al, 2009). This places huge demands on overstretched services as well as having large cost implications for the NHS (Murphy et al, 2013).