Tackling Physical Inactivity: A Resource for Raising Awareness in Physiotherapists

Original Editors - Jason Chang, Andrea Christoforou, Maria Cuddihy, Christine Gorsek, Annika Höbler as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

INTRODUCTION TO WIKI RESOURCES[edit | edit source]

PHYSICAL INACTIVITY: THE PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM[edit | edit source]

Physical inactivity has been deemed the “biggest public health problem of the 21st century”[1] and has been shown to kill more people than smoking, diabetes and obesity combined[2] . It is ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, killing approximately 3.2 million (~6% of the total deaths) people annually and accounting for approximately 32.1 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs; ~2.1% of global DALYs) annually[3].

|

Figure 1.[2] |

The major burden of disease attributed to physical inactivity is a result of its established role as one of the main risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer. In 2008, NCDs were responsible for 63% of the 57 million deaths worldwide[4] , with physical inactivity estimated to be directly responsible for 6% of the disease burden from coronary heart disease, 7% of type 2 diabetes and 10% of each of breast and colon cancers[5]. If physical inactivity were eliminated, this would translate to an estimated 5.3 million deaths being averted each year, or, more realistically, 533000 or 1.3 million with physical inactivity being reduced by 10% or 25%, respectively[5]. These figures do not include the increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to other factors, such as adiposity, raised blood glucose concentrations and high blood pressure, which are directly affected by physical inactivity[6].

A recent analysis of global data collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 31.1% of adults (aged 15 years or older) worldwide are physically inactive[7]. For this analysis, physical inactivity was defined as not achieving the equivalent of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity at least 5 days per week or 20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity at least 3 days per week[7]. Inactivity was found to increase with age and socio-economic status[7]. For adolescents aged 13 to 15 years old, the problem appears to be worse, with more than 80% reportedly not achieving the public health goal of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day, and with girls being less active than boys[7]. Figure x below (Jason’s figure, adapted from BHF report) summarises the levels of inactivity, defined as not meeting the recommended national physical activity guidelines at that time, for the countries of the UK. In the UK, the relationship between socio-economic status and physical inactivity is reversed, with individuals in the lowest income bracket displaying higher levels of inactivity than those in the highest (BHF 2012).

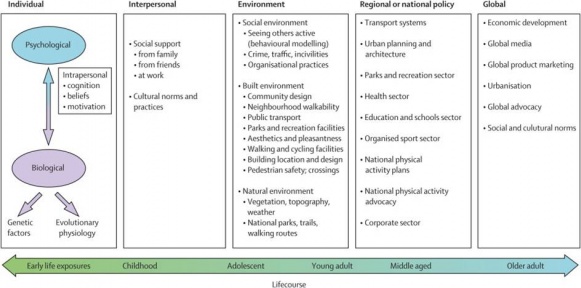

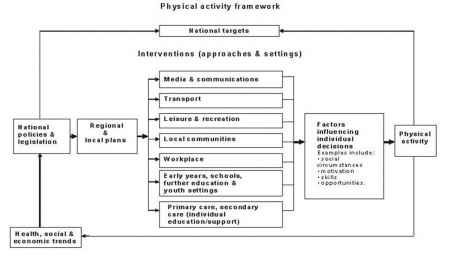

The factors contributing to this “physical inactivity pandemic” (add ref) go beyond personal (e.g. as reported in BHF 2012 and/or Maz’s table; ref BHF 2012 – chpt 6). It is being recognised more and more that social, cultural, environmental and national and global policy level factors also play a substantial role, resulting in an ecological model of physical activity as illustrated in the Figure 3. (from Bauman et al 2012 Lancet – ecological model). Thus, interventions aimed at all levels are necessary for the problem to be properly addressed[8], as illustrated in the Physical Activity Framework proposed by NICE Figure 4. (ref. show http://publications.nice.org.uk/physical-activity-and-the-environment-ph8/public-health-need-and-practice#physical-activity-framework).

|

| Figure 3. |

|

| Figure 4. |

To that end, physical activity initiatives have propped up around the world. Leading the global forum, WHO hav adopted the WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health (ref doc/site), publishing recommended physical activity guidelines (ref site) and providing implementation aids to support national policymakers[8]. In the UK, Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries' Chief Medical Officers[9] was recently (year?) published, providing updated national guidelines, the evidence for them and guidance for their local implementation. Thus, as physical activity is finally being recognised as a public health priority, all eyes on issue…(a concluding statement? something about it only recently being considered a public health priority (Kohl 2012) - here or at end of next section showing evidence for PA )

FURTHER READING[edit | edit source]

The Lancet 2012;

CPD[edit | edit source]

(reflection?) Questionnaires used to collect this information are not without limitations and flaws...fraught with self-report bias (ref) and vary in reliability and validity in different age groups and clinical populations (ref; http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/9/1/103). Reflect on how these limitations may impact these analyses and affect interpretation.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY: THE BEST MEDICINE[edit | edit source]

All parts of the body which have a function if used in moderation and exercised in labour in which each is accustomed, become thereby healthy, well developed and age more slowly; but if unused and left idle they become liable to disease, defective in growth and age quickly.

- Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, ca 400 B.C.

PA Definition Box (Jason)

Evidence[edit | edit source]

In addition to the high prevalence and corresponding harmful health consequences of physical inactivity, physical activity has become a public health priority by virtue of the body of evidence supporting its effectiveness as a whole-body/holistic? health intervention[8] While physical activity has only recently (ca 2000) factored into the public health agenda[8], quantitative evidence of its widespread health benefits has been formally emerging since 1950s when Professor Morris and colleagues showed that men engaged in work requiring a level of physical activity (e.g. active conductor or postmen) were less likely to suffer from coronary heart disease than men with sedentary jobs (e.g. bus drivers or clerical workers)[10] Sixty years later, the evidence continues to materialize with a recent study suggesting that exercise can be as effective as drug interventions in the prevention and rehabilitation of number of health conditions[11].

The Youtube video by Dr. Mike Evans below creatively presents some of the most compelling evidence of the effectiveness of physical activity in maintaining health and well-being:

| [12] |

23 and 1/2 Hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health? |

PHYSIOTHERAPISTS AS "PHYSICAL ACTIVITY CHAMPIONS"

[edit | edit source]

“First, do no harm” - Hippocratic Oath

Physiotherapists have the potential to make a substantial impact on individual, community and public health. Their holistic, biopsychosocial (ICF refs), and non-invasive approach, professional autonomy (ref? HCPC?), specialist knowledge (e.g. pathophysiology and movement) and skill set (e.g. physical activity or exercise prescription) (), relatively prolonged patient contact time and varied clinical practice settings and clinical population places the physiotherapist in the ideal position for the widespread promotion of physical activity (Khan guest editorial: http://sunshinephysio.com/resources/articles/PhysicalActivityChampions.pdf) Dean 2009 and WCPT ppt show Figure).

In the past, physiotherapy intervention, including exercise prescription, has predominantly focused on the restoration of function resulting from an acute incident or on the maintenance of function in neurological or cardio-respiratory disease (Verhagen and Engbers 2008 role of physio;). However, the shift in public health need toward the prevention or management of chronic lifestyle conditions, including NCDs, obesity, osteoarthritis and depression (public health refs), and the mitigation of the effects of ageing an increasing ageing population (find refs) has demanded a shift in the role of the physiotherapist in addressing this need, through the promotion of physical activity (as well as other lifestyle changes (Dean)). Recognising this emerging role and “professional and ethical responsibility” (Dean), physiotherapy professional bodies around the world have brought physical activity promotion to the forefront of their agendas (eg WCPT, CSP, APTA, Oz?). In Scotland, in accordance with the Allied Health Professionals (AHP) National Delivery Plan (ref), which includes physiotherapists, the AHP Directors Group have formed the PAHA and have made a pledge to “…work with a range of partners to increase the level of physical activity in Scotland” (ref).

As physical activity participation is influenced by multiple factors, including individual, socio-cultural, environmental and government policy (Figure from above), there is potential for physiotherapists to intervene at all levels (eg NICE guidelines - show pathway figure??). Below follows guidance to raise awareness of the roles physiotherapists may assume in the promotion of physical activity. Particular attention is paid at the level of the individual given the established role of the physiotherapist in the clinical setting and the impact that can be made in every patient encounter (O’Donaghue and Dean 2010)…(may need to change our headers…), while …(something about how we give a flavor of the other roles)

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND THE INDIVIDUAL[edit | edit source]

THE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY "VITAL SIGN"[edit | edit source]

Assessment is arguably the most important tool in the physiotherapists arsenal, enabling the acquisition of information for a clinically-reasoned, holistic and patient-centred approach to diagnosis and subsequent management (ref???). Despite the evidence of the widespread health risks imposed by physical inactivity [link to relevant section] and the opposing preventative and protective effects of regular physical activity and reduced sedentary behaviour [link to relevant section], patients’ habitual physical activity and sedentary levels are generally not explicitly assessed as part of the standard physiotherapy assessment [13].Yet, all patients coming into contact with a physiotherapist suffer from and/or are susceptible to the effects of physical inactivity, regardless of their presenting complaint. Thus, the assessment of patients’ habitual physical activity and sedentary levels has a relevant place in the physiotherapy examination[14].

In the general medicine community, physical activity has been declared the fifth vital sign[15] – a modifiable sign that should be assessed at every clinical encounter[15][16]. GPs encouraged to assess for a while now…with GPPAQ (incorporate Annika’s info on GPPAQ here)

Strange that physios have not (ref Verhagen & Engbers: The physios role in pa promotion)..but with increased role in primary care…

Similarly and more relevantly, as part of the Physical Activity and Health Alliance Pledge, AHP Directors and stakeholders have pledged to: “Agree a form of questioning and brief intervention for each patient, every time and embed this in all AHP services”[17]. Incorporate ScotPASQ and stuff here…

Different approaches may be used to measure levels of physical activity (e.g. observation, heart rate monitors, motion sensors), but questionnaires are likely to be the most appropriate in the context of a physiotherapy assessment, given time and resource constraints[14]. They should be relevant to the participants’ ages and education levels, particularly if self-administered[14].

The General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ).

Recommendations made by NICE Public Health Intervention Guidance published in March 2006 state that primary care practitioners should take advantage of every opportunity to establish whether an adult is achieving the proposed amount of activity per week and, where appropriate, use their expertise to advise on a suitable intervention. The UK’s General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) is an investigatory tool employed in general practice to produce a simple physical activity guide[18]. It takes approximately 30 seconds to complete and an additional 2-3 minutes to group the patient into one of four levels of activity[19]. The GPPAQ comprises good face validity and has been deemed suitable for routine use in general practice. It has good construct validity as the Physical Activity Index produced from the GPPAQ has the expected relationship with other measures. It is also repeatable, producing repeated results (NICE 2006). NB: also assesses sedentary behaviour...

[link to questionnaire https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/192450/GPPAQ_-_pdf_version.pdf]

Scottish Physical Activity Questionnaire (SPAQ).(remove? And provide link of all questionnaires)

The Scottish physical activity questionnaire (SPAQ) was generated to assist in the recall of physical activity, both leisure and occupational, over a seven day period and to identify the stage of exercise behaviour change[20]. It has been shown to be reliable. Concurrent validity is strong however criterion validity is limited. Limitations are apparent in the measurement of occupation walking. However, it can be used to measure outcomes of physical activity with conviction when its limitations are taken into account [20]

Scottish Physical Activity Screening Questionnaire (PASQ).

Most recently…The Scottish Physical Activity Screening Question (Scot-PASQ) was generated and validated by NHS Health Scotland in collaboration with The University of Edinburgh. The Scot-PASQ has been employed in an NHS Physical Activity Pilot that began in Scotland in January 2013. The pilot is aiming to evaluate the feasibility of applying a Physical Activity Pathway providing Brief Advice and Brief Interventions in Scottish Primary Care. The Scot-PASQ may further improved following the pilot and AHPs are encouraged to utalise the Scot-PASQ in their practice and give feedback regarding any changes that are required. Practitioners are prompted to partake in the e-learning module ‘Raising the Issue of Physical Activity’[21].

[link to screening tool: Screening Tool]

Exercise Vital Sign Questions (blend in better as an ‘informal’ approach, although this is the basis of Scot-PASQ, right?? Maybe use this info as evidence of potential efficacy of Scot-PASQ?)

It is advised that two exercise vital sign (EVS) questions are posed to the patient in order to compare their weekly activities with the recommended guidelines (www.exerciseismedicine.org). Based on the Kaiser Permanente experience, two questions are proposed to the patient:

1. ‘On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate or greater physical activity?’

2. ‘On those days, how many minutes do you engage in activity at this level?’

It is debateable if querying a patient’s activity level challenges their behaviour and perspective but they should at least be informed regarding the effect it may have on them[15].

Patient notes should be documented in accordance with Section 6, Record keeping and information governance, in the CSP Quality Assurance Standards 2012[22] and questionnaire results should be documented within the patient medical records[16]. Following a diagnosis, management should be implemented[15].

To do: Update Scot-PASQ, and possibly remove SPAQ and replace with reference to following tool: http://www.parcph.org/subjSearch.aspx

CPD – Suggest ‘Raising the Issue of Physical Activity’[21].

MOBILISING BEHAVIOUR CHANGE[edit | edit source]

Physical activity (e.g. as per the recommended guidelines) is a complex, multifactorial (see Fig?) and multi-dimensional (see Fig?) health behaviour[23][24]. The role of the physiotherapist in counselling a patient to adopt, change or maintain such behaviour can be equally complex. It may involve forming a partnership with the patient[25], defining the target behaviour (e.g. increasing physical activity and decreasing sedentary behaviour), exploring and addressing the unique combination of personal, socio-cultural, environmental, policy factors underlying the patient’s behaviour[23] [26] and identifying the most suitable (patient-centred) approach(es) to mobilise and help the patient sustain the behaviour[27]. Long-term adherence to physical activity is essential if the long-term health benefits are to be realised[28].

Several theoretical models of and counselling approaches for health behaviour change have been developed[29][30]. A working knowledge of these models and the various approaches to their practical application is another essential tool in the physiotherapist’s arsenal, if s/he is to help effect and sustain behaviour change in the patient. A number of the most prominent is highlighted below.

Theoretical Models of Health Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Table 1 (in excel sheet; adapted from Dean 2009 part II and Elder 1999) provides a brief description of and practical suggestions for some of the most prominent theoretical models. Among these, the Transtheoretical Model [31] has received the most attention in the field due to its ease and utility in clinical practice[29][32]. It assumes that a patient’s readiness to change falls within one of five stages, based on his/her level of engagement with the particular health behaviour[31] (Tables 1 and 2):

Table2 adapted from Dean 2009

Determining the patient’s stage of readiness through a series of specific questions facilitates the identification of strategies or subsequent interventions that will be most effective in guiding the patient to progress to the next stage [30][32]. The Health Behavior Change Research (HBCR) workgroup at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa provide a series of relevant questionnaires for applying the TTM to physical activity (Health Behavior Change Research). The American Council on Exercise® offers practical guidance on how to use the TTM to help a patient make healthy behaviour changes (American Council on Exercise). In particular, motivational Interviewing, described below, has gained wide acceptance as an effective means of motivating behaviour change within the TTM framework[33].

While the TTM and other health behaviour models suffer from limitations ([32]for TTM; others?), they are useful in helping to understand the potentially modifiable factors that underlie behaviour and behaviour change. Taken together, these theoretical models converge on key, interrelated determinants of behaviour change[30][34]. In particular, self-efficacy (i.e. one’s perceived ability to execute the behaviour) [35][36][32][37], barrier identification and negotiation[38][26] (see Box of barriers), S.M.A.R.T, patient-centred goal-setting[39][40] and feedback, including reinforcement and follow-up[29][26][41] have been found to significantly impact physical activity behaviour change. A physiotherapist can work with the patient to modulate these factors to promote behaviour change[29][34], using various approaches[42], as outlined below.

Methods to Promote Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Behavioural counselling encompasses a spectrum of interventions, which can be rooted in one or more behavioural theories e.g. TTM[27]. Scotland’s new pathway serves…(NB: need to incorporate below more smoothly so it doesn’t focus on the new pathway and Scotland, but just uses the pathway as a way of introducing BA and BIs…)

As part of the new Physical Activity Pathway introduced in Scotland in 2013[43] after raising the issue of physical activity and screening (i.e. Q1 and Q2 in Scot-PASQ described above), the clinician assesses the patient’s readiness to change (i.e. Q3, http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/20415-QuickReferenceGuide.pdf - possible to cut picture of pathway into the two parts of assessment and behaviour intervention??), the response to which determines which behavioural intervention to deliver. These are Brief Advice and Brief Intervention ( http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/20415-QuickReferenceGuide.pdf ) – two approaches which do not require extensive training to be effectively executed (CSP – Brief Interventions: Evidence Briefing (physical activity…)). A third approach, Motivational Interviewing, is also recommended, although this requires additional training [44].

Brief Advice[edit | edit source]

Brief Advice consists of a short (~3 minute), structured conversation with the patient aimed at raising awareness of the benefits of physical activity, exploring barriers and identifying some solutions (http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/21759-Physical%20Activity%20Pathway%20For%20Secondary%20Care.pdf). Brief Advice may be suitable for a patient in the early stages of readiness i.e.precontemplation and contemplation[30] or for a patient in the maintenance stage, requiring only reinforcement to maintain the behaviour[27]. A short video describing Brief Advice can be found on NHS NES Knowledge Network, along with other promotional videos for the new Physical Activity Pathway (http://www.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/home/portals-and-topics/health-improvement/hphs/nhs-physical-activity-promotion.aspx).

Brief Intervention[edit | edit source]

Brief Interventions are longer (3-20 minutes) structured conversations, which delve deeper into patient’s needs, preferences and circumstances with the aim of motivating and supporting the patient toward the behaviour change in a non-judgmental and positive manner. More time is spent discussing the benefits of the behaviour change, addressing barriers, setting goals and building confidence http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/21759-Physical%20Activity%20Pathway%20For%20Secondary%20Care.pdf. A short video describing Brief Interventions can be found on NHS NES Knowledge Network, along with other promotional videos for the new Physical Activity Pathway (http://www.knowledge.scot.nhs.uk/home/portals-and-topics/health-improvement/hphs/nhs-physical-activity-promotion.aspx).

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational Interviewing (Rollnick and Miller 1995 – see refs in doc below) is a behaviour change intervention that has been most recently (2009) defined as “…a collaborative, person-centred form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change”

This short interview with William R Miller, the founder of MI, describes approach’s origin: http://www.motivationalinterview.org/quick_links/about_mi.html

MI consists of two phases, the first in which intrinsic motivation is reinforced and the second in which commitment to change is enhanced[45]. It is based on five general principles (Miller 1983), which are listed in TableX (adapted Table 1 from Shinitzky) and modelled in a series of videos provided as a learning resource for pharmacy students at Montash University: http://www.monash.edu.au/pharm/current/step-up/motivational-interviewing/.

OARS, or Open-ended questions, Affirmations, Reflections and Summaries, represent the core counselling skills employed in MI (http://www.motivationalinterview.org/Documents/1%20A%20MI%20Definition%20Principles%20&%20Approach%20V4%20012911.pdf). MI challenges the patient in a supportive and self-reflective manner, working under the assumption that the patient knows what is best for him/herself. The clinician’s role is to collaborate with, guide and support the patient through his/her journey of behaviour change (ref??). Although distinct from the Transtheoretical Model[44], MI is often used in conjunction with it, as it has been shown to facilitate progression through the stages[33]. In particular, it has been shown to be effective in those who are in the low stages of readiness to change[46] and in a range of health settings[45].

As MI requires standardised training for optimal delivery [45], it presents an excellent CPD opportunity for physiotherapists[16]. The following site serves as a useful starting point: http://www.motivationalinterview.org/index.html.

Section Conclusion?

Several models and methods exist to aid the physiotherapist in promoting health behaviour change in his/her patient and the adoption of self-management skills for long-term adherence (ref? Resource? → http://www.mhhe.com/hper/physed/clw/02corb.pdf). Perhaps, however, one of the most powerful adjuncts?/accessories? is role modelling the behaviour – ie practice what you preach[29]. (need to reword this better…)

Key Resource? Exercise is Medicine book? A few practical chapters on Motivating patient…

CPD – Health Behaviour Change - learning module for practitioners

http://elearning.healthscotland.com/blocks/behaviour/index.php

Take time to reflect on your level of activity, stage of readiness. Are you in a position to be a role model for a healthy level of physical activity?

Take an example of one of your regular or current patients? What is their level of physical activity? Have you ever discussed physical activity? If so, in what stage of the TTM model would they be?

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY "ON PRESCRIPTION"[edit | edit source]

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND THE COMMUNITY[edit | edit source]

KEY RESOURCES[edit | edit source]

REFERENCES[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century [warm up] .fckLRBr J Sports Med 2009;43(1):1-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Khan KM, Tunaiji HA. As different as Venus and Mars: time to distinguish efficacy (can it work?) from effectiveness (does it work?) [warm up] . Br J Sports Med 2011;45(10):759-760.

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO).Prevalence of physical inactivity 2013; Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Global Health Observatory (GHO).Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) 2013; Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/index.html Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380(9838):219-29.

- ↑ Hallal PC, Bauman AE, Heath GW, Kohl HW, Lee IM, Pratt M. Physical activity: more of the same is not enough [comment] . Lancet 2012;380(9838):190-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380(9838):247-57.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Kohl HW 3rd, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet 2012;380(9838):294-305.

- ↑ Department of Health. Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers 2011; Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/start-active-stay-active-a-report-on-physical-activity-from-the-four-home-countries-chief-medical-officers Accessed 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Paffenbarger RS Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM. A history of physical activity, cardiovascular health and longevity: the scientific contributions of Jeremy N Morris, DSc, DPH, FRCP. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(5):1184-92

- ↑ Naci H, Ioannidis JPA. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ 2013;347:f5577.

- ↑ DocMikeEvans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo [last accessed 18/11/13]

- ↑ Petty, N.J. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. 2001. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Hussey J, Wilson F. Measurement of Activity Levels is an important part of physiotherapy assessment. Physiotherapy 2003;89(10):585-93.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Sallis, R. Developing healthcare systems to support exercise: exercise as the fifth vital sign. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;45:473-4

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Khan KM, Weiler R, Blair SN. Prescribing exercise in primary care. BMJ 2011; 343

- ↑ Physical Activity and Health Alliance. AHP Directors Physical Activity Pledge 2009. Available at: http://www.paha.org.uk/Announcement/ahp-directors-physical-activity-pledge. (accessed 30 October 2013).

- ↑ Department of Health. General Practice Physical Activity QuestionnairefckLR2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/general-practice-physical-activity- questionnaire-gppaq (accessed 3 November 2013).

- ↑ NHS. The General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire A Screening to Assess Adult Physical Activity Levels, within primary care. 2009. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/general-practice-physical-activity-questionnaire-gppaq [Accessed 3 November 2013]

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lowther M, Mutrie N, Loughlan C, McFarlane C. Development of a Scottish physical activity questionnaire: a tool for use in physical activity interventions. British Journal of Sports Medicine 1999;33:244–9.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Physical Activity and Health Alliance. Scottish Physical Activity Screening Question 2012. Available at: http://www.paha.org.uk/Resource/scottish-physical-activity-screening question-scot-pasq (accessed 3 November 2013)

- ↑ Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Quality Assurance Standards 2012. Available at: fckLRhttp://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/professionalism/csp-expectations-members/quality-assurance-standards (accessed 3 November 2013).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380(9838):258-71.

- ↑ Pettee Gabriel KK, Morrow JR Jr, Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex and multidimensional behaviour. J Phys Act Health 2012;9(Suppl 1):S11-8.

- ↑ Jonas S, Phillips EM. ACSM’s Exercise is MedicineTM: A Clinician’s Guide to Exercise Prescription. American College of Sports Medicine 2009 Philadelphia

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther 1993;73(11):771-82.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Steptoe A, Kerry S, Rink E, Hilton S. The impact of behavioural counselling on stage of change in fat intake, physical activity, and cigarette smoking in adults at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health 2001;91(2):265-9.

- ↑ Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Medicine 2013:1-10.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Dean E. Physical therapy in the 21st century (Part II): Evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):354-68.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behaviour change in primary care. Am J Prev Med 1999;17(4):275-84.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Prochaska JO and DiClemente CC. Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward An Integrative Model of Change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(3):390-5.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Nigg CR, Geller KS, Motl RW, Horwath CC, Wertin KK, Dishman RK. A research agenda to examine the efficacy and relevance of the transtheoretical model for physical activity behaviour. Psychol Sport Exerc 2011;12(1):7-12.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Shinitzky HE, Kub J. The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs 2001;18(3):178-85.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Rhodes RE and Fiala B. Building motivation and sustainability into the prescription and recommendations for physical activity and exercise therapy: The evidence. Physiother Theory Prac 2009;25(5-6):424-41.

- ↑ Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman, 1997.

- ↑ O’Hea EL, Boudreaux ED, Jeffries SK, Carmack Taylor CL, Scarinci IC, Brantley PJ. Stage of change movement across three health behaviors: the role of self-efficacy. Am J Health Promot 2004;19(2):94-102.

- ↑ Dishman RK, Motl RW, Sallis JF, Dunn AL, Birnbaum AS, Welk GJ, Bedimo-Rung AL, Voorhees CC, Jobe JB. Self-management strategies mediate self-efficacy and physical activity. Am J Prev Med 2005;29(1):10-8.

- ↑ Al-Otaibi HH. Measuring stages of change, perceived barriers and self efficacy for physical activity in Saudi Arabia. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2013;14(2):1009-16.

- ↑ Nothwehr F, Yang J. Goal setting frequency and the use of behavioural strategies related to diet and physical activity. Health Educ Res 2007;22(4):532-8.

- ↑ Shilts MK, Horowitz M, Townsend MS. Goal setting as a strategy for dietary and physical activity behaviour change: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 2004;19(2):81-93.

- ↑ DiClemente CC, Marinilli AS, Singh M, Bellino LE. The role of feedback in the process of health behaviour change. Am J Health Behav 2001;25(3):217-27.

- ↑ CSP Facilitating Behaviour Change, Evidence Briefing. Available at: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/facilitating-behaviour-change-evidence-briefing (accessed 19 Nov 2013).

- ↑ NHS Health Scotland. Physical Active Pathway For Secondary Care. Available at: http://www.healthscotland.com/documents/21759.aspx (accessed 21 Nov 2013).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Miller WR and Rollnick S. Ten Things that Motivational Interviewing Is Not. Behav Cog Psych 2009;37(2):129-40.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Martins RK and McNeil DW. Review of Motivational Interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29(4):283-93.

- ↑ Resnicow K, DiIlorio C, Soet JE, Borrelli B, Hecht J, Ernst D. Motivational Interviewing in Health Promotion: It Sounds Like Something Is Changing. Health Psychol 2002;21(5):444-451.

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.