Otitis Media

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Otitis media, commonly known as a middle ear infection, is a condition characterized by inflammation or infection of the middle ear. It often occurs following a cold, sore throat, or respiratory infection. This condition is particularly prevalent in children, with about 75% experiencing at least one episode by the age of 3.

It is a spectrum of diseases that includes:[1]

- Acute otitis media (AOM): A sudden onset of infection or inflammation in the middle ear.

- Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM): Persistent or recurrent inflammation or infection of the middle ear.

- Otitis media with effusion (OME): Fluid accumulation in the middle ear without active infection.

This article explores the spectrum of otitis media, its etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment modalities.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Otitis media is a complex condition that results from various factors such as infections, allergies, and environmental elements. Causes and risk factors of Otitis Media:

Infectious Agents:[edit | edit source]

Bacterial Pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis are major contributors.

Viral Pathogens: Respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus.[3]

Immune System Factors:[edit | edit source]

Decreased immunity due to conditions like HIV, diabetes, and other immune deficiencies.

Genetic Predisposition:[edit | edit source]

Ethnicity: Children who are Native American, Hispanic and Alaska Natives have more ear infections than children of other ethnic groups.

Certain genetic factors may increase susceptibility to otitis media.[4]

Anatomic Abnormalities:[edit | edit source]

Abnormalities of the palate and tensor veli palatini.

Ciliary dysfunction.

Environmental Factors:[edit | edit source]

Passive Smoke Exposure: Especially in children.[5]

Cochlear Implants:[edit | edit source]

Individuals with cochlear implants may be at an increased risk.[8]

Other Factors:[edit | edit source]

Vitamin A deficiency.

Daycare attendance.

Lower socioeconomic status.

Family history of recurrent AOM.[9]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of otitis media involves infectious, allergic, and environmental factors, including decreased immunity, genetic predisposition, mucin abnormalities, and anatomic abnormalities. It is more common in males than in females and peaks between six and 12 months of life, declining after age five. The condition begins as an inflammatory process following a viral upper respiratory tract infection, leading to Eustachian tube obstruction and decreased ventilation in the middle ear.[10]

Statistics show that around 80% of children are affected by it. Additionally, between 80% and 90% of all children experience otitis media with an effusion before they even start school. Although otitis media is less prevalent in adults, some sub-populations are still at risk. For instance, people who have a history of recurrent OM in childhood, cleft palate, immunodeficiency, or immunocompromised status are more susceptible to this condition.[11]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

AOM is not always preceded by a viral upper respiratory tract infection that also affects the mucosa of the nose, nasopharynx, and Eustachian tubes.[12]

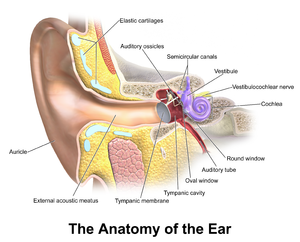

Infection of the middle ear results from nasopharyngeal organisms migrating via the eustachian tube. The anatomy of the eustachian tube in younger children is immature, typically being short, straight, wide (only becoming more oblique as the child grows), meaning infection blocks the narrow section of the Eustachian tube. Inflammation in the Eustachian tube leads to fluid accumulation in the middle ear. Bacterial infection of the middle ear results from nasopharyngeal organisms migrating via the Eustachian tube, with common causative bacteria including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.[13][14]

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms of ear infection in children may include:

- Irritability

- Headache

- Disturbed or restless sleep

- Poor feeding or anorexia

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Pulling or tugging at the ears.

- About two-thirds of patients may also have a low-grade fever.[15]

The American Academy of Pediatrics has established guidelines for diagnosing acute otitis media, which involve the presence of moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane or new onset of otorrhea (ear pain) not caused by otitis externa, or mild tympanic membrane bulging with recent onset of ear pain or erythema. These criteria are meant to assist primary care clinicians in making accurate diagnoses and informed clinical decisions, but not to replace their clinical judgment.[16]

On otoscopy, the tympanic membrane (TM) looks erythematous and may be bulging. If this fluid pressure has perforated the TM, small tear are visible with purulent discharge in the auditory canal. Patients may have a conductive hearing loss or a cervical lymphadenopathy.

It is important to test and document the function of the facial nerve (due to its anatomical course through the middle ear). Examination should also include checking for any intracranial complications, cervical lymphadenopathy, and signs of infection in the throat and oral cavity.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of otitis media is primarily based on clinical findings combined with supporting signs and symptoms. Several diagnostic tools are available to aid in the diagnosis of otitis media, including:

- Pneumatic otoscopy: This is a useful technique for diagnosing AOM and OME, as it allows for the visualization of the tympanic membrane and the detection of middle ear effusion. It is 70% to 90% sensitive and specific for determining the presence of middle ear infection.

- Tympanometry: This method helps in detecting the presence of middle ear fluid and documenting bacterial etiology. It can be used in conjunction with pneumatic otoscopy to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis.

- Acoustic reflectometry: This test can be used to detect middle ear effusion, but it has lower sensitivity and specificity compared to pneumatic otoscopy and tympanometry. It must be correlated with the clinical examination.

- Otoscopy: A doctor will diagnose a middle ear infection by performing a physical exam and an ear exam using an otoscope, which allows for the visualization of the eardrum and the detection of any abnormalities.

Overall, otoscopy remains a primary diagnostic tool.[17]

Treatment / Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of otitis media, or middle ear infection, varies depending on the severity of the condition and the age of the patient. The following is a detailed elaboration of the treatment options for otitis media:

- Monitoring: In some cases, particularly in lower-risk children, observation without antibiotic therapy may be an option. This approach involves closely monitoring the child's condition and reevaluating the need for antibiotics if symptoms persist or worsen.

- Pain management: Adequate analgesia is recommended for all children with acute otitis media to alleviate pain and discomfort. Pain-relieving medications can be used to help reduce fever and improve the child's overall well-being. To relieve pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be used. The use of antibiotics to treat otitis media early on is a controversial issue and varies based on the guidelines of the country.[18]However, there is evidence of oral antibiotics in suppurative AOM.

- Antibiotic therapy: If antibiotics are necessary, the choice of medication and duration of treatment depend on the severity of the infection and the patient's age. Children with uncomplicated AOM may be treated with amoxicillin for 10 days, while those with severe AOM or complications may require intravenous antibiotics for a longer period.

- Antihistamines and decongestants: These medications are not recommended for children with acute otitis media or OME, as their use may not be effective and could potentially cause side effects.

- Tympanostomy tubes: In cases where recurrent or persistent otitis media is not responding to other treatments, surgical intervention may be necessary. Tympanostomy tubes are small tubes that are inserted into the eardrum to help equalize pressure and allow the middle ear to drain fluid. These tubes typically fall out on their own within a few months.

- Myringotomy: This is a surgical procedure in which the eardrum is cut to allow trapped fluid to drain and relieve pain. It is not commonly performed in the United States due to the availability of other treatment options.

- Hygiene and prevention: Parents and caregivers can help prevent otitis media by practicing good hygiene, such as washing hands frequently, avoiding smoking in the home and car, and keeping children away from people with known infections. Additionally, ensuring that children are up-to-date on their vaccinations can help reduce the risk of otitis media.

Resources[edit | edit source]

American Academy of Pediatrics

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Rettig, E., & Tunkel, D. E. (2014). Contemporary Concepts in Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 47(5), 651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2014.06.006

- ↑ Meherali, S., Campbell, A., Hartling, L., & Scott, S. (2019). Understanding Parents’ Experiences and Information Needs on Pediatric Acute Otitis Media: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Patient Experience, 6(1), 53-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373518771362

- ↑ Seppälä E, Sillanpää S, Nurminen N, Huhtala H, Toppari J, Ilonen J, Veijola R, Knip M, Sipilä M, Laranne J, Oikarinen S, Hyöty H. Human enterovirus and rhinovirus infections are associated with otitis media in a prospective birth cohort study. J Clin Virol. 2016 Dec;85:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.10.010. Epub 2016 Oct 20. PMID: 27780081.

- ↑ Mittal R, Robalino G, Gerring R, Chan B, Yan D, Grati M, Liu XZ. Immunity genes and susceptibility to otitis media: a comprehensive review. J Genet Genomics. 2014 Nov 20;41(11):567-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 31. PMID: 25434680.

- ↑ Strachan, D. P., & Cook, D. G. (1997). Health effects of passive smoking. 4. Parental smoking, middle ear disease and adenotonsillectomy in children. Thorax, 53(1), 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.53.1.50

- ↑ Ardiç C, Yavuz E. Effect of breastfeeding on common pediatric infections: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018 Apr 1;116(2):126-132. English, Spanish. doi: 10.5546/aap.2018.eng.126. PMID: 29557599.

- ↑ Ardiç C, Yavuz E. Effect of breastfeeding on common pediatric infections: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018 Apr 1;116(2):126-132. English, Spanish. doi: 10.5546/aap.2018.eng.126. PMID: 29557599.

- ↑ Vila, P. M., Ghogomu, N. T., Odom-John, A. R., Hullar, T. E., & Hirose, K. (2017). Infectious complications of pediatric cochlear implants are highly influenced by otitis media. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 97, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.02.026

- ↑ Kraemer MJ, Richardson MA, Weiss NS, Furukawa CT, Shapiro GG, Pierson WE, Bierman CW. Risk factors for persistent middle-ear effusions. Otitis media, catarrh, cigarette smoke exposure, and atopy. JAMA. 1983 Feb 25;249(8):1022-5. PMID: 6681641.

- ↑ Usonis V, Jackowska T, Petraitiene S, Sapala A, Neculau A, Stryjewska I, Devadiga R, Tafalla M, Holl K. Incidence of acute otitis media in children below 6 years of age seen in medical practices in five East European countries. BMC Pediatr. 2016 Jul 26;16:108. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0638-2. PMID: 27457584; PMCID: PMC4960887.

- ↑ M. Schilder, A. G., Chonmaitree, T., Cripps, A. W., Rosenfeld, R. M., Casselbrant, M. L., Haggard, M. P., & Venekamp, R. P. (2016). Otitis media. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.63

- ↑ Winther B, Alper CM, Mandel EM, Doyle WJ, Hendley JO. Temporal relationships between colds, upper respiratory viruses detected by polymerase chain reaction, and otitis media in young children followed through a typical cold season. Pediatrics. 2007 Jun;119(6):1069-75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3294. PMID: 17545372.

- ↑ Fireman P. Otitis media and eustachian tube dysfunction: connection to allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997 Feb;99(2):S787-97. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70130-1. PMID: 9042072.

- ↑ Fireman P. Eustachian tube obstruction and allergy: a role in otitis media with effusion? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985 Aug;76(2 Pt 1):137-40. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(85)90690-6. PMID: 4019946.

- ↑ Kontiokari T, Koivunen P, Niemelä M, Pokka T, Uhari M. Symptoms of acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998 Aug;17(8):676-9. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199808000-00003. PMID: 9726339.

- ↑ Siddiq S, Grainger J. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media: American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines 2013. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2015 Aug;100(4):193-7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305550. Epub 2014 Nov 12. PMID: 25395494.

- ↑ Ramakrishnan K, Sparks RA, Berryhill WE. Diagnosis and treatment of otitis media. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Dec 1;76(11):1650-8. Erratum in: Am Fam Physician. 2008 Jul 1;78(1):30. Dosage error in article text. PMID: 18092706.

- ↑ Rettig E, Tunkel DE. Contemporary concepts in management of acute otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014 Oct;47(5):651-72. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2014.06.006. Epub 2014 Aug 1. PMID: 25213276; PMCID: PMC4393005.