Management of Chronic Ankle Instability

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson and Matt Huey

Definition of Chronic Ankle Instability (CAI)[edit | edit source]

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) has been defined as “repetitive bouts of lateral ankle instability resulting in numerous ankle sprains.”[1] Chronic instability refers to feeling of apprehension in the ankle, “giving way” and recurrent ankle sprains, persisting for a minimum of 6 months after the initial sprain.[2]Symptoms include:[2]

- Lateral ankle pain

- Chronic swelling

- Difficulty walking on uneven terrain

Based on the International Classification of Function, Health and Disability (ICF) model, the effects of CAI on function and health include:

- In terms of impairments:[3]

- increased ligamentous laxity

- proprioceptive deficits

- In terms of activity limitations:[3]

- inability to walk

- inability to jump

- In terms of participation:[3]

- cessation of sport

- withdrawing from or decreasing occupational involvement

- decreasing the level of exercise

- change in type of sport

Long Term Outcomes[edit | edit source]

Patients with CAI have a loss of physical quality of life. Treatments may improve stability but are taking a long time and may require specialised equipment. [2]Seven years post-ankle inversion trauma study by Konradsen et al[4] revealed the following:

- 32% of patients reported chronic complaints of pain, swelling or recurrent sprains

- 72% of the subjects with residual disability reported that they were functionally impaired by their ankle

- 4% of patients experienced pain at rest and were severely disabled

- 19% were bothered by repeated inversion injuries

- 43% of these subjects felt that they could compensate by using an external ankle support

- 85% of people who develop CAI after unilateral sprain reported problems in the contralateral ankle.

According to Hertel [5]one sprain guarantees another. [5][2]Struijs and Kerkhoffs[6]indicated that 30% recurrence of sprain happened within the first year after the injury.[2]

Additional reported long-term outcomes include:

- Articular cartilage defects on the medial side of the joint due to:[2]

- Tearing of ATFL and CFL

- Altering and increasing peak cartilage strain

- Leading to tibiotalar cartilage degeneration (OA)

- Anterior talar positional fault [7]

- Altered movement patterns in unstable ankles:[2]

- Landing in more dorsiflexion in an attempt to minimise reliance on lateral ligaments and increase bony stability

- In drop jump: greater maximum calcaneal eversion and frontal displacement of the body

- Faster time to peak ground reaction force in drop landing

- Greater medial ground reaction force.

- Metatarsal height is lowered during a terminal swing of gait

Mechanical and Functional Instability[edit | edit source]

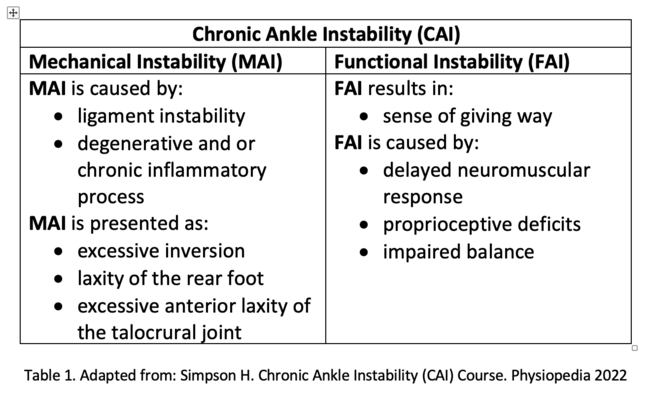

There are two commonly accepted subgroups of CAI: mechanical instability and functional instability. [2][3]In Hertel's model [8] of ankle stability, mechanical and functional instability are part of a continuum. Recurrent sprain occurs when both conditions are present. [8]

Mechanical Instability[edit | edit source]

Mechanical instability is referred to as pathological ligamentous laxity about the ankle-joint complex[9]Mechanical instability may result from various anatomic changes that are present in isolation or in combination. They can lead to pathologies that are responsible for ankle instability. [3]

Functional Instability[edit | edit source]

There is no universally approved definition of functional ankle instability.[10] Based on definition established by Evans et al.,[11] functional instability is a subjective complaint of weakness.[11] Lentell and his colleagues [12] describes functional instability as ankle pain and the perception that the ankle is less functional than the other side or the situation prior to the injury. [12] Tropp et al. [13] concluded, that a joint motion that did not exceed normal physiologic limits, but was no longer controlled voluntarily, defines functional instability. [13]

Impaired proprioceptive and neuromuscular control can be responsible for functional instability.[8]

Table 1 summerises the causes and the results of mechanical and functional ankle instability:[2]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic procedures may help clinicians to confirm the presence of various ankle deficiencies, including range of motion limitation and perceived disability that leads to define a condition. The choice of the diagnostic tool should be based on the scientific evidence suggesting its consistent positive utility:[14]

- Anterior drawer test is performed in slight knee flexion to relax the gastrocnemius, but Kovaleski et al[15] suggested a testing position with the knee flexed to 90° and the ankle in 10° of plantar flexion to isolate the anterior talofibular ligament. [15] A bilateral comparison is recommended. [14] Excessive anterior translation and the lack of a solid end feel indicate positive test results.

- Stress radiography is used to quantify the extent of ankle-joint laxity. It shows the separation of the bony joint structures while a force is applied. Clinically it helps to identify excessive strain within the ligamentous structures. A total anterior translation greater than 9 mm or translation greater than 5 mm (or both) when compared with the contralateral side indicates significant laxity of the anterior talofibular ligament. Pathologic laxity of the CF ligament is demonstrated by a talar tilt angle greater than 10° in total or more than 5° greater than the contralateral limb. [14]

- MRI is not conclusive. Negative MRI results must be viewed with caution in a symptomatic patient and arthroscopy should be considered.[16]

- Diagnostic ultrasound offers moderate to strong confirmation of lateral ligamentous injury, evidence suggests.[17]It shows an increased lateral ligament lengths during the anterior drawer and talar tilt tests among individuals with a history of CAI.[18]

- Stable force plates are suggested for gait and hop stability assessment:[19]

- Imaged guided injections of cortisone as clinical diagnostic tool: based on the review of the published literature for evidence, Delphi-based consensus of the experts from the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology indicated that intraarticular foot and ankle anaesthetic injections performed under imaging guidance offers precise information about pain source.[21]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

While a surgical approach for treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament injuries is reserved for special cases, a conservative management is the treatment of choice. [22] Currently available modalities of choice include:[2]

- Neuromuscular training

- Balance training

- Mobilisation

- Neuromuscular control by peroneii

- Braces and taping

- Flexibility and strength training

Neuromuscular Training[edit | edit source]

- de Vries et al [23]concluded, that neuromuscular training alone demonstrates a positive short term outcome and patients had better function. [23]He stated that this type of training is a basis for the majority of conservative treatment regimes.[23][2]

- Study by Kim et al[24]has found an altered gait pattern in athletes with unstable ankles. They showed a relatively inverted ankle position during the initial contact and midstance. Incorporating a six-week neuromuscular training immediately changed ankle orientation toward a relatively more inverted direction during jump landing, but showed no effect on walking and running.[24]

- According to Guzmán-Muñoz and his colleagues[25]a four-week neuromuscular training improved postural control in college volleyball players with functional ankle instability (FAI) .[25]

Guide to Neuromuscular Training[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular training is an"unconscious activation of dynamic restraints in preparation and in response to joint motion and load to maintain and restore functional joint stability".[2]

Goals of neuromuscular training:

Exercises[edit | edit source]

Exercises are performed in closed chain and functional positions:

- single limb stance on wobble board or balance mat

- single limb ball toss

- single leg theraband kicks and step downs

Examples:

Balance Training[edit | edit source]

- Investigating functional ankle instability and Health-Related Quality of Life, Arnold et al[27]concluded that balance training can affect a multiple of joints and produce overall improvement.[2]

- McKeon and his colleagues [19] showed that balance training significantly improves static postural control and dynamic postural control.[2]

- A prospective cohort study by Sefton et al [28] found that rehabilitation affects sensorimotor system function.[2]

- Based on the review of randomised controlled trials, Mollà Casanova et al [29] concluded, that balance training significantly improves functionality, instability, and dynamic balance outcomes in people with chronic ankle instability. [29]

Guide to Balance Training[edit | edit source]

The following balance measures should guide clinical practice:

- foot pressure measures: center-of pressure (COP) excursion [30]

- time-to-boundary (TTB)

- peak plantar analysis

- Do not correlate to function (de Vries)

- bilaterally impaired after an acute sprain (Wikstrom)

- Measured in time-to-boundary (TBB) after landing and SEBT (Vicon Motion Analysis Laboratory)

- Hip strategy.

- Hip strategy creates larger shear forces with ground – giving way……and take longer to stabilize.

- Land with less hip and knee flexion (Gribble) and more dorsiflexed ankle (Pope).

- Pronation and supination of the foot assist to maintain body’s centre of gravity.

- More supinated foot noted during stance to increase mechanical stability (Pope 2011).

- Centre of gravity more lateral and easier to “sprain”

Proprioception[edit | edit source]

Proprioception, including both kinesthesia and JPS, of the injured ankle of patients with CAI was impaired, compared with the uninjured contralateral limbs and healthy people. Proprioception varied depending on different movement directions and test methodologies. The use of more detailed measurements of proprioception and interventions for restoring the deficits are recommended in the clinical management of CAI.[31]

Mobilisation[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular Control by Peroneii[edit | edit source]

Braces and taping[edit | edit source]

Flexibility and Strength Training[edit | edit source]

- Proprioception, including both kinesthesia and JPS, of the injured ankle of patients with CAI was impaired, compared with the uninjured contralateral limbs and healthy people. Proprioception varied depending on different movement directions and test methodologies. The use of more detailed measurements of proprioception and interventions for restoring the deficits are recommended in the clinical management of CAI.[31]

add text here relating to diagnostic tests for the condition

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Hertel J. Functional Anatomy, Pathomechanics, and Pathophysiology of Lateral Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):364-375.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Simpson H. Chronic Ankle Instability Course. Physiopedia 2022

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Hiller CE, Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM. Chronic ankle instability: evolution of the model. Journal of athletic training. 2011 Mar;46(2):133-41.

- ↑ Konradsen L, Bech L, Ehrenbjerg M, Nickelsen T. Seven years follow-up after ankle inversion trauma. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002 Jun;12(3):129-35.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hertel J. Immobilisation for acute severe ankle sprain. Lancet. 2009 Feb 14;373(9663):524-6.

- ↑ Struijs PA, Kerkhoffs GM. Ankle sprain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010 May 13;2010:1115.

- ↑ Wikstrom EA, Hubbard TJ. Talar positional fault in persons with chronic ankle instability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Aug;91(8):1267-71.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hertel J. Functional Anatomy, Pathomechanics, and Pathophysiology of Lateral Ankle Instability. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):364-375

- ↑ Tropp H. Commentary: Functional Ankle Instability Revisited. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):512-515.

- ↑ Konradsen L. Factors Contributing to Chronic Ankle Instability: Kinesthesia and Joint Position Sense. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):381-385.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Evans GA, Hardcastle P, Frenyo AD. Acute rupture of the lateral ligament of the ankle. To suture or not to suture? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984 Mar;66(2):209-12

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lentell G, Katzman LL, Walters MR. The Relationship between Muscle Function and Ankle Stability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1990;11(12):605-11.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Tropp H, Odenrick P, Gillquist J. Stabilometry recordings in functional and mechanical instability of the ankle joint. Int J Sports Med. 1985 Jun;6(3):180-2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Gribble PA. Evaluating and differentiating ankle instability. Journal of athletic training. 2019 Jun;54(6):617-27.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kovaleski JE, Norrell PM, Heitman RJ, Hollis JM, Pearsall AW. Knee and ankle position, anterior drawer laxity, and stiffness of the ankle complex. J Athl Train. 2008 May-Jun;43(3):242-8.

- ↑ Joshy S, Abdulkadir U, Chaganti S, Sullivan B, Hariharan K. Accuracy of MRI scan in the diagnosis of ligamentous and chondral pathology in the ankle. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010 Jun;16(2):78-80.

- ↑ Oae K, Takao M, Uchio Y, Ochi M. Evaluation of anterior talofibular ligament injury with stress radiography, ultrasonography and MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2010 Jan;39(1):41-7.

- ↑ Croy T, Saliba SA, Saliba E, Anderson MW, Hertel J. Differences in lateral ankle laxity measured via stress ultrasonography in individuals with chronic ankle instability, ankle sprain copers, and healthy individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Jul;42(7):593-600.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 McKeon PO, Ingersoll CD, Kerrigan DC, Saliba E, Bennett BC, Hertel J. Balance training improves function and postural control in those with chronic ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008 Oct;40(10):1810-9.

- ↑ Vicon. Vicon Gait and Posture Biomechanics. 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6JMr-ZPbjQ [last accessed 9/07/2022]

- ↑ Sconfienza LM, Adriaensen M, Albano D, Alcala-Galiano A, Allen G, Aparisi Gómez MP, Aringhieri G, Bazzocchi A, Beggs I, Chianca V, Corazza A, Dalili D, De Dea M, Del Cura JL, Di Pietto F, Drakonaki E, Facal de Castro F, Filippiadis D, Gitto S, Grainger AJ, Greenwood S, Gupta H, Isaac A, Ivanoski S, Khanna M, Klauser A, Mansour R, Martin S, Mascarenhas V, Mauri G, McCarthy C, McKean D, McNally E, Melaki K, Messina C, Mirón Mombiela R, Moutinho R, Olchowy C, Orlandi D, Prada González R, Prakash M, Posadzy M, Rutkauskas S, Snoj Ž, Tagliafico AS, Talaska A, Tomas X, Vasilevska Nikodinovska V, Vucetic J, Wilson D, Zaottini F, Zappia M, Obradov M. Clinical indications for image-guided interventional procedures in the musculoskeletal system: a Delphi-based consensus paper from the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (ESSR)-part VI, foot and ankle. Eur Radiol. 2022 Feb;32(2):1384-1394

- ↑ Aicale R, Maffulli N. Chronic lateral ankle instability: topical review. Foot & Ankle International. 2020 Dec;41(12):1571-81.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 de Vries JS, Krips R, Sierevelt IN, Blankevoort L, van Dijk CN. Interventions for treating chronic ankle instability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Aug 10;(8):CD004124.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Kim E, Choi H, Cha JH, Park JC, Kim T. Effects of Neuromuscular Training on the Rear-foot Angle Kinematics in Elite Women Field Hockey Players with Chronic Ankle Instability. J Sports Sci Med. 2017 Mar 1;16(1):137-146.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Guzmán-Muñoz E, Daigre-Prieto M, Soto-Santander K, Concha-Cisternas Y, Méndez-Rebolledo G, Sazo-Rodríguez S, Valdés-Badilla P. The effects of neuromuscular training on the postural control of university volleyball players with functional ankle instability: A pilot study. Archivos de medicina del deporte. 2019;35(5):283-7

- ↑ Loudon JK, Santos MJ, Franks L, Liu W. The effectiveness of active exercise as an intervention for functional ankle instability: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2008;38(7):553-63.

- ↑ Arnold BL, Wright CJ, Ross SE. Functional ankle instability and health-related quality of life. J Athl Train. 2011 Nov-Dec;46(6):634-41.

- ↑ Sefton JM, Yarar C, Hicks-Little CA, Berry JW, Cordova ML. Six weeks of balance training improves sensorimotor function in individuals with chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Feb;41(2):81-9.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Mollà-Casanova S, Inglés M, Serra-Añó P. Effects of balance training on functionality, ankle instability, and dynamic balance outcomes in people with chronic ankle instability: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2021 Dec;35(12):1694-709.

- ↑ Yousefi M, Sadeghi H, Ilbiegi S, Ebrahimabadi Z, Kakavand M, Wikstrom EA. Center of pressure excursion and muscle activation during gait initiation in individuals with and without chronic ankle instability. Journal of Biomechanics,2020, 18.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Ma T, Li Q, Song Y, Hua Y. Chronic ankle instability is associated with proprioception deficits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of sport and health science. 2021 Mar 1;10(2):182-91.