Back and Upper Leg Regional Pain and Gait Deviations

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Lucinda hampton and Nupur Smit Shah

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Gait deviations are likely related to the development of and / or associated with musculoskeletal pain syndromes. It is often the complaint of pain that will lead a patient to physiotherapy. It is the role of the physiotherapist to educate the patient on the aetiology of their pain while treating and correcting the noted gait deviation.[1]

"The kinesiopathologic model was designed specifically to describe the mechanically related processes proposed to contribute to the development and course of low back pain (LBP). The basic premise is that LBP results from the repeated use of direction-specific (flexion, extension, rotation, lateral bending, or a combination of these) stereotypic movement and alignment patterns in the lumbar spine. The model proposes that the patterns begin as the result of adaptations of the musculoskeletal and neural systems due to repeated use of specific movements and alignments during daily activities. The nature and rate of the adaptations can be modified by intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of the individual, for example, sex, anthropometrics, or typical activities of the person. The typical pattern is one in which, during performance of a movement (eg, forward bending) or assumption of a posture (eg, sitting), the lumbar spine moves into its available range in a specific direction more readily than other joints, such as the knees, hips, or thoracic spine."[2]

With the patient's pain as a guide, a goal of musculoskeletal physiotherapy is to identify the anatomical structures associated with the reported pain. Physiotherapists utilise orthopeadic tests to assist in symptom source identification. However, these clinical tests are often inconsistent in their ability to accurately identify the anatomical source of the patient's symptoms. Additionally, there is a poor correlation between imaging results and symptom source identification in the absence of trauma or pathology. These two statements suggest that musculoskeletal pain may often be anatomically and structurally indeterminable. The kinesiopathological approach is an alternative to these more traditional methods of diagnosis. This methods calls for clinical practice to be guided by the identification and modification of kinematic or motor control impairments within a musculoskeletal function. By correcting deviant movement patterns to a more idealised movement pattern unique to a particular individual, subjective pain can be improved and function can be reestablished.[3]

Back Regional Pain[edit | edit source]

Potential gait deviations associated with LBP:[1]

- Decreased gait velocity, less than 1-1.4 metres per second[4]

- Shortened step length[4]

- Slow gait cadence

- Stiff counter rotation between the thoracic spine and the lumbar spine[4]

- Changes in expected vertical oscillation of centre of mass (COM)

- Loud foot strike

- Can demonstrate either an increased or decreased pelvic tilt

- Can demonstrate either increased or decreased hip extension during terminal stance

- Decrease in big toe dorsiflexion, resulting in a functional hallux limitus

Hip Regional Pain[edit | edit source]

| Region of Pain | Relavent Diagnoses | Expected Gait Deviations |

|---|---|---|

| Hip Region |

| |

| Lateral Hip |

|

|

| Anterior Hip |

Knee Region Pain[edit | edit source]

| Region of Pain | Relavent Diagnoses | Expected Gait Deviations |

|---|---|---|

| Knee Region |

|

|

| Anterior Knee | Patellofemoral arthralgia |

|

| Lateral Knee | Iliotibial (IT) band syndrome |

|

Back and Upper Leg Region Special Topics[edit | edit source]

Lumbar Stenosis Gait Deviation[edit | edit source]

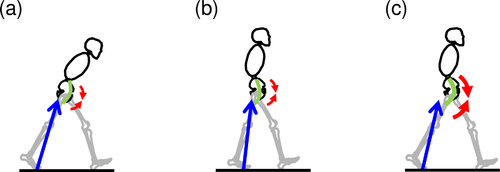

Lumbar stenosis is a common back pain diagnosis in the elderly population. A patient with lumbar stenosis does not stand or ambulate with upright posture, and tend to avoid lumbar extension to decrease and or avoid pain. They may present with a tendency to walk bent over, and lean on their grocery cart or walker. They will likely demonstrate one of two gait deviations to alleviate symptoms associated with lumbar spinal stenosis:[9]

- Figure A: Trunk flexion posture with an increased step length and hip extension angle[9], and an absent lumbar joint moment into extension.[1]

- Figure B: Trunk upright posture with a decreased step length and hip extension angle[9] and an absent lumbar joint moment into extension.[1]

- Figure C: Ideal walking posture of healthy people[9]

Dropped Head Syndrome[edit | edit source]

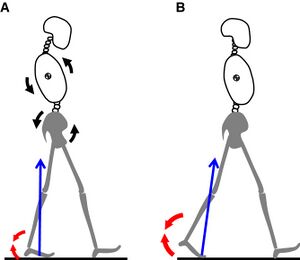

Dropped head syndrome (DHS) is a relatively rare cervical kyphotic deformity which Chas symptoms of: neck pain, restrictions to ambulation, and impaired horizontal gaze. Due to the interconnected nature of the spine, the relationship between cervical alignment relative to other parts of the spinal column can have an effect on the pelvis and lower limbs during dynamic activities. Patients with DHS demonstrate altered kinematics and kinematics of the lower limbs during walking duet o changes in the inclination of the head and trunk. This may cause deviant gait features and altered motor control compared to healthy individuals. Similar findings have been reported with the use of a smartphone while walking. The increased cervical flexion angle affects: cervical loading, walking speed, and muscle activity of the lower limbs.[10]

- Figure A represents an individual with DHS: backward leaning posture of the thorax, increased ankle-joint dorsiflexion angle, and relatively shorter stride length. [10]

- Figure B is ideal walking posture: upright erect posture with decreased ankle dorsiflexion angle allowing for more movement coming from the ankle to propel forward and up. [10]

Geriatric gait[edit | edit source]

I want to talk for a moment about what would be classified as geriatric gait. They may be in pain or just, just maybe a geriatric gait. The spatiotemporal changes that occur in old folks is they walk slow, less than 1.4 metre per second or one metre per second. They take shorter steps or strides. They have a slower cadence. We've all seen this. In the kinematics, they have a late or a prolonged heel contact. They're going to have a decreased up and down motion, a decreased vertical oscillation of centre of mass, could have decreased hip extension, may have increased forward lean that we saw with lumbar stenosis gait compensation, and they may have decreased arm swing. Often the older people will just walk with their hands held behind their back and not even swing their arms. This is some interesting work by DaVita and colleagues, originally published in 2002. It's talking about the age lower extremity kinematic forces, comparing it between old folks and young folks. So the amount of propulsive force when walking and running varies across the joints in the lower extremity. How much is being propelled forward or up. Old folks, geriatrics, elderly people use hip joint moments more than ankle, whereas young people use the ankle to propel forward, ankle plantarflexion. They use that more than the hip. So if you look at the table, the propulsive force in the elderly is maybe 75%, whereas in the young it's one-third, roughly speaking, whereas down at the ankle, old folks only use the ankle to propel forward by 12%, a very small amount. So I think this is an interesting thing that we can take advantage of when we get into gait training and intervention with our old folks that are increased risk for falling or having pain, we can get them to use their ankle more. So this graph is the AP force, the fore-aft force that occurs during stance phase. So the horizontal axis is just stance phase, the vertical axis is the force that's the brake or the propel forward, the fore and aft that occurs. And there's in the first half of the first period of stance, there's a negative braking force stopping you from going forward and in the second half from midfoot to forefoot rocker or terminal stance, that's when you propel forward, also propelling up. So DeVita and colleagues did some, they were able to amplify and augment this and provide feedback to a group of normal subjects, trying to get them to increase that propulsive force with an instrumented treadmill and the camera right in front of the treadmill. And they said, we want you to increase that, increase it. And both the old people and the young people were able to increase the total lower extremity propulsive force given that feedback. That was real-time feedback. But what they discovered was both the old people and the young people, to generate that increased force to get it above the threshold, both the young and the old used their hip. They didn't use the ankle. So they did a follow-up study where they gave the feedback and just look at ankle joint plantarflexion external moment and they were able to, with augmented feedback, increase the propulsive force coming from the ankle joint. We don't have in our clinic, these augmented feedbacks, instrumented treadmills, and sophisticated equipment, but what I take from this is when we give a verbal cue, not that I want you to push more, I want you to propel up, leave an imprint from your foot, move from your ankle. Again, we're going to talk about internal cueing and external cueing. Basically the soundbite that I use is I want you to walk with spring in your step. That's going to get you to use the ankle if the gait deviation is decreased vertical oscillation of centre of mass or prolonged heel contact.

Osteoarthritis and Total Joint Replacements[edit | edit source]

Next region of pain I want to talk about is hip pain, osteoarthritic pain and the gait deviations that can continue status post total hip joint replacement. Oftentimes patient with hip osteoarthritis develops gait deviations and has a habit and even when they have a normal joint, they may continue to walk with that habit, that deviated habit. The next pain syndrome I want to touch on is knee pain associated with osteoarthritis and/or again status post total knee joint replacement, that gait deviations may continue.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Optional Recommended Reading:

- Harris-Hayes M, Czuppon S, Van Dillen LR, Steger-May K, Sahrmann S, Schootman M, Salsich GB, Clohisy JC, Mueller MJ. Movement-pattern training to improve function in people with chronic hip joint pain: a feasibility randomized clinical trial. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jun;46(6):452-61.

- Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, Bove AM, Foster SN, Mueller MJ, Clohisy JC, Fitzgerald GK. Movement pattern training compared with standard strengthening and flexibility among patients with hip-related groin pain: results of a pilot multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2020 Mar 1;6(1):e000707.

- Lamoth CJ, Meijer OG, Daffertshofer A, Wuisman PI, Beek PJ. Effects of chronic low back pain on trunk coordination and back muscle activity during walking: changes in motor control. European Spine Journal. 2006 Feb;15(1):23-40.

Clinical Outcome Measures:

- Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) Download PDF here

- Please view the following short video for an overview of the FABER test used in the assessment of pathologies at the hip, lumbar and sacroiliac region.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Howell, D, Back and Upper Leg Regional Pain and Gait Deviations. Gait Analysis. Physioplus. 2022

- ↑ Cholewicki J, Breen A, Popovich Jr JM, Reeves NP, Sahrmann SA, Van Dillen LR, Vleeming A, Hodges PW. Can biomechanics research lead to more effective treatment of low back pain? A point-counterpoint debate. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2019 Jun;49(6):425-36.

- ↑ Lehman GJ. The role and value of symptom-modification approaches in musculoskeletal practice. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2018 Jun;48(6):430-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Lamoth CJ, Meijer OG, Daffertshofer A, Wuisman PI, Beek PJ. Effects of chronic low back pain on trunk coordination and back muscle activity during walking: changes in motor control. European Spine Journal. 2006 Feb;15(1):23-40.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Harris-Hayes M, Steger-May K, Bove AM, Foster SN, Mueller MJ, Clohisy JC, Fitzgerald GK. Movement pattern training compared with standard strengthening and flexibility among patients with hip-related groin pain: results of a pilot multicentre randomised clinical trial. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2020 Mar 1;6(1):e000707.

- ↑ Harris-Hayes M, Czuppon S, Van Dillen LR, Steger-May K, Sahrmann S, Schootman M, Salsich GB, Clohisy JC, Mueller MJ. Movement-pattern training to improve function in people with chronic hip joint pain: a feasibility randomized clinical trial. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jun;46(6):452-61.

- ↑ Ranawat AS, Gaudiani MA, Slullitel PA, Satalich J, Rebolledo BJ. Foot progression angle walking test: a dynamic diagnostic assessment for femoroacetabular impingement and hip instability. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017 Jan 10;5(1):2325967116679641.

- ↑ Lewis CL, Sahrmann SA, Moran DW. Effect of hip angle on anterior hip joint force during gait. Gait & posture. 2010 Oct 1;32(4):603-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Igawa T, Katsuhira J, Hosaka A, Uchikoshi K, Ishihara S, Matsudaira K. Kinetic and kinematic variables affecting trunk flexion during level walking in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. PLoS One. 2018 May 10;13(5):e0197228.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Igawa T, Ishii K, Suzuki A, Ui H, Urata R, Isogai N, Sasao Y, Nishiyama M, Funao H. Dynamic alignment changes during level walking in patients with dropped head syndrome: Analyses using a three-dimensional motion analysis system. Scientific reports. 2021 Sep 14;11(1):1-0.

- ↑ YouTube. Fabers Test Hip and SIJ | Clinical Physio Premium. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6trjwpyjdM [last accessed 23/06/2022]