Biomechanics of the Dancer’s Ankle and Foot

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Assessing an injury in a ballet patient can be a daunting task. After gaining a basic understanding of the foot and ankle anatomy, applying biomechanical principles can help the therapist form a clear picture of the treatment plan. Dancers spend the majority of their time in extreme positions, mostly plantar and dorsiflexion of their ankle. If professionals (dancers and therapists) do not understand the requirements for these positions and the demands incurred, compensation can occur further up the kinetic chain, resulting in pain and injury.

The “Ideal” Anatomy for a Ballet Foot[edit | edit source]

While there is no "ideal" ballet foot, the following features could be considered optimal:[1]

- Maximal plantarflexion in the talocrural joint[2]

- Maximal dorsiflexion in the first metatarsophalangeal joint

- A medium arch

- The best foot shape for dance is a square foot with equal length of the first and second ray

- Straight toes

- Strong intrinsic and extrinsic muscles

- Maximum flexibility, control, strength and endurance[3]

- Ideally, a genetic aspect of some form of hypermobility

The "Ideal" Biomechanics for a Ballet Foot[edit | edit source]

- Ideal turnout,[4] as a result of strong external hip rotators

- Strong flexible back

- Control and coordination of hypermobility

- Active stabilisation of the trunk

- Excellent ballet technique

Movements of the Foot and Ankle[edit | edit source]

Ankle[edit | edit source]

Foot (excluding toes)[edit | edit source]

Toes[edit | edit source]

- Dorsiflexion

- Plantarflexion

- Abduction

- Often accompanies dorsiflexion

- Adduction

- Often accompanies plantarflexion

The combination of movements across subtalar and tibiotalar joints causes supination and pronation.[1]

Ankle ROM[edit | edit source]

The range of motion (ROM) in the ankle joint is vital to the ballet dancer. Inadequate ROM can cause pain, compensation and injury.

Average ROM[edit | edit source]

The expected plantarflexion range of motion in an average human is 30-50 degrees, while the expected dorsiflexion range of motion with the knee extended is 10 degrees. When the knee is flexed, the expected range of dorsiflexion is 20 degrees.[5] This results in an average through range measurement of 40 - 70 degrees.

A ballet dancer will work towards a through-range measurement of 90 degrees, with some reports of up to 101 degrees in elite dancers.[6][7]

Important Aspects to Consider with ROM[edit | edit source]

- Degree of winging when pointing

- 'Over the box' movement in a pointe shoe

- Releve height achieved

Due to the repetitive nature of training for the ballet discipline and the strong need to be on pointe, which is a position of plantarflexion, a ballerina will often present with increased range of plantarflexion.[8] This reciprocally causes a decrease in dorsiflexion, unless this is adequately trained as well. As a dancer advances in their discipline, this is a very common complication[9] and needs to be addressed by treating professionals. Another common observation is that, when a dancer advances in ballet an they move from demipointe positions into full pointe positions, often an increase in foot and ankle pain is noticed. [10] A dancer needs to be educated on their foot biomechanics and that the main hinge point in their foot has to be the ankle joint. This joint requires a full range of motion while the smaller joints in the foot often have to remain in a locked position.

“Muscle strength deficits contribute to faulty mechanics, including increased ankle inversion/eversion compensation in an effort to get en pointe/maintain position, decreased stability once there, knuckling under and decreased plantarflexion range of motion to allow ideal positioning over body over toes”[10]

Importance of Alignment[edit | edit source]

A strong, well-aligned foot supports the full alignment up the chain. Poor alignment is a major risk factor of foot and ankle injuries in all ballet dancers, recreational and professional.[11] Good alignment is essential to improving control, strength and injury prevention in the ankle and foot

Good Alignment[edit | edit source]

When en pointe and demi-pointe, our body weight is transferred down through the tibia to the talus. The talus forms a joint in front with the navicular bone, which in turn forms joints with the cuneiforms and with the 1st, 2nd and 3rd metatarsals and toes. Bodyweight should be more focused through the medial or inner three toes if the dancer is to transfer body weight forces correctly through footwear to the floor. Care needs to be taken to ensure that weight is taken through the 2nd metatarsal when moving through the foot or standing on demipointe/pointe will allow the 5 bones of the midfoot to “lock” ensuring a more stable foot to work with. Engagement of deep external hip rotators as the turnout of the hip will lead to supination of the rearfoot (lifted arch position), which will also lock up the middle region of the foot.

In the “perfect” demipointe/pointe position, the centre of the ankle should be aligned with the dancer’s second toe. One method that is relatively easy to use that can help both the teacher and dancer understand “right from wrong” alignment involves the use of a pen or marking pen. The student is asked to locate and mark the mid point between the malleoli. A straight line is then drawn between this mark and the midline of the second toe. When standing on demipointe or pointe, this line should remain vertical.

Importance of alignment for calf strength development[edit | edit source]

Correct alignment of the foot, ankle, leg, hip and spine is essential for the correct engagement of muscles for the choreography.

The incorrect alignment of the foot, ankle, leg, hip and spine will result in the dancer trying to force the movements and this can result in an overuse injury of muscles that are not designed for dancing. The consequences of this is constant stiffness and tightness around the hip joints, thighs and calves, which will require management.

Three key elements in a "Good" Ballet foot[edit | edit source]

1. Arches[edit | edit source]

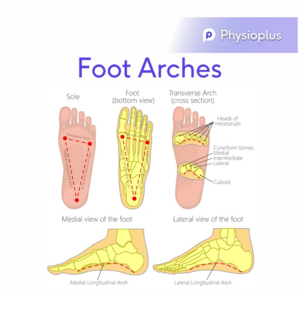

There are 3 arches in the foot

- Medial longitudinal

- designed to allow the foot to trespass uneven surfaces and absorb shock

- Lateral longitudinal

- stability

- Anterior transverse

- aids in support and shock absorption, stability and balance, especially in releve

These arches contribute to normal weight distribution, stability and distribution in dancing. The arches are formed by the tarsal and metatarsal bones. The shape allows them to act as a spring, bearing the weight of the body and absorbing the shock produced during dancing

The height of the arches is determined by the bone structure and influenced by muscles and the flexibility of ligaments. When referring to arches in a dancers foot, they are commonly described as:

- High

- Medium

- Flat

A medium arch is considered ideal. It allows good shock absorption and allows flexibility with the ligaments not too tight as to restrict movement.

The importance of arches in ballet[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, the arches of the foot are important for optimal function, but for a ballet dancer, there are interesting complications to irregular arches.

- Weak lateral longitudinal arch

- Contributes to sickling and supination

- Weak and flattened medial longitudinal arch

- Contributes to winging and pronation

- Pronounced medial longitudinal arch

- Results in supination or rolling to the outside of the foot

2. Intrinsic Foot Muscles[edit | edit source]

The biggest role of the intrinsic foot muscles to a ballet dancer is to oppose the clawing effect of the long flexors of the toes. When the toes are flexed at the metatarsal phalangeal joints, the action of the intrinsic muscles helps to keep the interphalangeal joints straight.

3. Plantar Fascia[edit | edit source]

Another key structure is the plantar fascia which is a band of connective tissue that runs on the plantar or bottom surface of the foot. It acts as the main support for the medial longitudinal arch and, therefore, plays a key role in stabilizing the foot in action that requires pushing off the ground to propel such as jumping or running.

Turnout[edit | edit source]

For a dancer to have good turnout, they need range and strength further up the chain. When this is not the case, for example, a dancer does not have sufficient external rotation in the hips[12] to enable correct turnout, we usually find THREE compensations occurring: [4]

- Lower back

- A swayback posture, or lumbar hyperlordosis, with the combination of slightly flexed knees can cause an anterior pelvic tilt and greater hip flexion and the anterior capsule of the hip relaxes.

- Knees

- A slightly flexed knee can allow increased external rotation of the lower limbs. This also increases the amount of grip necessary by the toes to maintain the position. [13]

- Feet

- Hyperpronation, as described below, can appear to increase turnout by the abduction of the forefoot. This compensation causes increased lower back , knee and medial aspect of the foot tension. [14]

Hyperpronation[edit | edit source]

Hyperpronation, simply explained as excessive pronation of the ankle joint, often causes strain on the supporting structures, such as ligaments and tendons, on both the medial and the plantar aspect of the foot. this can lead to:

- Medial tibial stress syndrome

- Flexor hallucis longus tendonitis

- Plantar fasciitis

- Patellofemoral pain syndrome

- Retropatellar chondropathy

- Lower back pain

According to an article written by Nowacki et al[15], hyperpronation has also been seen to contribute to the following conditions:

- Non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries

- Sesamoiditis

- Achilles tendonitis

- Leg length discrepancies

- Stress fractures

- Hallux valgus

- Bunions

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Green-Smerdon M. Biomechanics of the Dancer’s Ankle and Foot Course. Physioplus, 2022.

- ↑ Gorwa J, Michnik R, Nowakowska-Lipiec K. In pursuit of the perfect dancer’s ballet foot. The footprint, stabilometric, pedobarographic parameters of professional ballet dancers. Biology. 2021 May;10(5):435.

- ↑ Öktem H, Pelin C, Kürkçüoğlu A, Merve İZ, Şençelikel T. Evaluation of posture and flexibility in ballet dancers. Anatomy. 2019;13(2):71-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Carter SL, Bryant AR, Hopper LS. An analysis of the foot in turnout using a dance specific 3D multi-segment foot model. Journal of foot and ankle research. 2019 Dec;12(1):1-1.

- ↑ Norkin CC, White DJ. Measurement of joint motion: a guide to goniometry. FA Davis; 2016 Nov 18.

- ↑ Russell JA, Kruse DW, Nevill AM, Koutedakis Y, Wyon MA. Measurement of the extreme ankle range of motion required by female ballet dancers. Foot & ankle specialist. 2010 Dec;3(6):324-30.

- ↑ Russell JA. Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives. Open access journal of sports medicine. 2013;4:199.

- ↑ Russell JA, Shave RM, Yoshioka H, Kruse DW, Koutedakis Y, Wyon MA. Magnetic resonance imaging of the ankle in female ballet dancers en pointe. Acta Radiologica. 2010 Jul 1;51(6):655-61.

- ↑ Russell JA, Kruse DW, Nevill AM, Koutedakis Y, Wyon MA. Measurement of the extreme ankle range of motion required by female ballet dancers. Foot & ankle specialist. 2010 Dec;3(6):324-30.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 En Pointe: What Ballet Dancers Should Know About Injury Prevention

- ↑ Biernacki JL, Stracciolini A, Fraser J, Micheli LJ, Sugimoto D. Risk factors for lower-extremity injuries in female ballet dancers: a systematic review. Clinical journal of sport medicine. 2021 Mar 1;31(2):e64-79.

- ↑ Kaufmann JE, Nelissen RG, Exner-Grave E, Gademan MG. Does forced or compensated turnout lead to musculoskeletal injuries in dancers? A systematic review on the complexity of causes. Journal of Biomechanics. 2021 Jan 4;114:110084.

- ↑ Carter SL, Duncan R, Weidemann AL, Hopper LS. Lower leg and foot contributions to turnout in female pre-professional dancers: a 3D kinematic analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2018 Oct 2;36(19):2217-25.

- ↑ Rietveld AB. Dancers’ and musicians’ injuries. Clinical rheumatology. 2013 Apr;32(4):425-34.

- ↑ Nowacki RM, Air ME, Rietveld AB. Hyperpronation in dancers incidence and relation to calcaneal angle. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2012 Sep 15;16(3):126-32.