Developing Physically Active and Sporty Kids - Injuries Specific to Children and Teenagers

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Wanda van Niekerk, Lucinda hampton and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

While physical activity levels are, in general, declining in children,[1] there are still large numbers of children and teenagers who participate in organised sports.[2] And, as is discussed here, participation in formal sports can lead to injuries and burnout. Thus, when working with children and adolescents, it is important to consider how children’s injuries are different to those seen in adults.

Before looking at common injuries in children, this page will introduce some basic measures to assess when working with young people.

Know Your Child’s Age[edit | edit source]

There are a number of other ages which must be considered when working with children, including their:[3]

- Developmental age

- Skeletal age

- General training age

- Sport-specific training age

- Relative age

It is also useful to monitor a child’s growth. This might include regular (e.g. quarterly) height measurements in standing, crook sitting and arm span. This monitoring can help to identify peak velocity height (i.e. the time when the child is growing the quickest), which is relevant for certain conditions discussed below. Table 1 shows typical growth per year.[3]

| Age | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 5 | 4.8 | 5 | 4.8 | 5 | 4.8 | 8.6 | 12 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

Common Injuries in Children[edit | edit source]

Causes of Injuries in Children[edit | edit source]

Injuries observed in children are often different to those seen in adult for the following reasons:[3]

- Weak attachment site (causing avulsion fractures):[4]

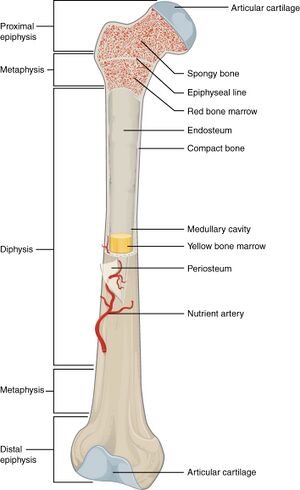

- Growth plate cartilage in children is less able to resist stress when compared to the articular cartilage in adults. It is also less resistant to shear and tension forces than the surrounding bone. This can lead to a failure of the physis when increased stress is applied (see Figures 1 and 2). Thus, in incidents where adults experience a complete tear of a ligament or joint dislocation, children might experience a growth plate separation. Children appear to be more prone to growth plate injuries during periods of rapid growth (see Table 1).

- A mismatch between bone growth and muscle growth, which leads to incoordinated movements, and thus fracture

- Weaker site at the physis can lead to fracture (see above)

- Greenstick fracture - i.e. a partial thickness fracture - the cortex and periosteum are disrupted on one side of the bone only. They are unaffected on the other side. but remain uninterrupted on the other.[5] They occur in elastic long bone.[3]

- Premature growth plate fracture = stress fracture

Types of Injuries[edit | edit source]

Apophysitis:[6]

- Caused by traction injuries to the cartilage and bony attachment of tendons

- Often related to overuse in children who are growing

- More common in the lower limb

- Less common, but osteochondroses are a group of conditions that affect the epiphysis (see Figure 1)[3]

- They occur when there are degenerative changes in the epiphyseal ossification centres of growing bones

- Caused by a temporary disruption of blood supply at the bone-cartilage complex, rather than traction

- They tend to resolve spontaneously, but should be monitored (surgery rarely required)

Metaphyseal fractures:[3]

- Fractures that affect the metaphysis of tubular bones[7]

- Occur most often in the forearm and lower leg

Avulsion fractures:

- Occur when there is a failure of the bone - a bone fragment is: “pulled away from its main body by soft tissue that is attached to it.”[8]

During periods of rapid growth in children, bone lengthens before the muscles and tendons have time to stretch and develop the necessary strength and coordination to control this new longer bone. This can lead to awkwardness in a child’s movement patterns.[3]

- Traumatic injuries lead to fractures of the bone or growth plate

- Strong incoordinated contractions of the muscles lead to avulsion fractures, rather than a tear of the muscle or tendon[3]

| Non-Articular (related to overuse) | Articular | Physeal |

|---|---|---|

| Osgood-Schlatter - tibial tubercle | Perthes - femoral head (ages 4 to 10) | Scheuermann’s disease - thoracic spine |

| Sinding Larsen Johansson - inferior pole of the patella | Kienbock’s - lunate wrist (more common in individuals aged 20 to 30 years) | Blount’s diease - proximal tibial growth plate (obese children aged 9 to 10 years)[9] |

| Sever’s - calacaneus | Kohlers - navicular (ages 2 to 8, more commonly 4 to 6 years[10]) | Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) impingement |

Osteochondritis dessicans:

|

Table 2 above lists common growth plate injuries / osteochondroses. These injuries tend to be treated conservatively except for those which affect the hip and the knee.[3] Table 3 below lists common types of fractures found in children.

| Metaphyseal Fracture | Avulsion Fracture | Growth Plate Fractures[3][11] |

|---|---|---|

| Mostly occur in the forearm and lower leg | Musculotendinous, with common sites including:[12]

|

Salter-Harris Types I and II

Salter-Harris Types III and IV

|

NB: even if an x-ray is normal, a history of severe rotational or shear force with localised swelling, bony tenderness and loss of function can indicate a growth plate fracture.[3]

Take Home Message[edit | edit source]

When a child presents with a traumatic injury, fracture should be considered. When pain appears related to overuse, or is long-term, growth plate injuries should be considered rather than tendinopathy or a ligament sprain, tendon or muscle tear.[3]

Management of Injuries in Children[edit | edit source]

Avulsion fractures:[3]

- Musculotendinous avulsion fractures are treated conservatively (i.e. the same as a grade III muscle tear)

- Ligamentous avulsion fractures are often treated with surgery, so the child will need to be assessed by a specialist

Metaphyseal fractures:[3]

- Must be immobilised

- Tend to heal quickly (3 weeks)

Growth plate injuries:[3]

- Usually requires conservative management / load management, especially in children who present with Osgood-Schlatter and Sever's

- If pain levels are high and the child has difficulty weight-bearing, they may require crutches for a time (1 to 2 weeks)

- Load is then gradually reintroduced

- A graded exposure approach to load can be adopted so that the system starts to accommodate and build up a tolerance to load

Osteochondosis / osteochondritis dissecans:[3]

- Refer the child to a specialist who can determine if immobilisation / surgical intervention is required

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Frömel K, Groffik D, Mitáš J, Madarasová Gecková A, Csányi T. Physical activity recommendations for segments of school days in adolescents: support for health behavior in secondary schools. Front Public Health. 2020;8:527442.

- ↑ Safe Kids Worldwide. Preventing sports-related injuries. Available from: https://www.safekids.org/preventing-sports-related-injuries (accessed 7 November 2021).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 Prowse T. Developing Physically Active and Sporty Kids - Injuries in Teens and Children Course. Physioplus, 2021.

- ↑ Caine D, DiFiori J, Maffulli N. Physeal injuries in children's and youth sports: reasons for concern?. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(9):749-60.

- ↑ Atanelov Z, Bentley TP. Greenstick Fracture. [Updated 2021 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513279/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Achar S, Yamanaka J. Apophysitis and osteochondrosis: common causes of pain in growing bones. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):610-8.

- ↑ Jones J. Metaphyseal fracture. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/metaphyseal-fracture-2 (accessed 9 November 2021).

- ↑ McCoy JS, Nelson R. Avulsion Fractures. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559168/

- ↑ Dakshina Murthy TS, De Leucio A. Blount Disease. [Updated 2021 Jul 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560923/

- ↑ Weerakkody Y, Bell D. Köhler disease. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/k-hler-disease (accessed 9 November 2021).

- ↑ Levine RH, Foris LA, Nezwek TA, et al. Salter Harris Fractures. [Updated 2021 Apr 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430688/

- ↑ Poultsides LA, Bedi A, Kelly BT. An algorithmic approach to mechanical hip pain. HSS J. 2012;8(3):213-24.

- ↑ Johns K, Mabrouk A, Tavarez MM. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. [Updated 2021 Aug 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538302/