Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (14/12/2019)

Original Editor - Norma Cervera Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Leah Milligan, Evan Thomas, Garima Gedamkar, WikiSysop, Admin, Naomi O'Reilly, Norma Cervera and Mason Trauger

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurological disorder with an adult onset around 54–67 years old, and it belongs to a group of conditions known as Motor Neurone Diseases (MND). Its clinical hallmark is the degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons, leading to progressive muscle atrophy and weakness, and ultimately to paralysis. Death, often resulting from swallowing problems and respiratory failure, usually occurs within 2–4 years from disease onset, although 5–10% of ALS patients survive over 10 years[1].

Image - Noted physicist Stephen Hawking [who suffered from ALS] enjoys zero gravity during a flight aboard a modified Boeing 727 aircraft owned by Zero Gravity Corp.

Physical therapy is an integral component of the ALS multidisciplinary team and is well grounded in rehabilitation and active living concepts. Despite the lack of a cure and rapidly progressive nature of the disease, physical therapy that is tailored to the individual’s needs and goals enables the client to live life to the fullest and with quality[2].

The incidence and prevalence increases with age and reaches a cumulative lifetime risk of 1 in 400 after 80 years old. Due to the projected aging of the global population, ALS cases are expected to increase by 69% in the next 25 years, and there is a need to identify causes, biomarkers and therapeutic targets for ALS[1].

Descriptions of the disease date back to at least 1824. In 1869, the connection between the symptoms and the underlying neurological problems (involvement of cortico-spinal tract) were first described by Jean-Martin Charcot. In 1874 Charcot began using the term amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The disease became widely publicised in the United States when it affected the famous baseball player Lou Gehrig, and later when the ice bucket challenge became popular in 2014.

The 2 minute video below gives a good introduction to ALS.

Background epidemiology to the disease[edit | edit source]

ALS is the most common form of Motor neuron disease in adults[4][5] The incidence of ALS is approximately 1-2.6 cases per 100 000 persons annually, with a prevelance of approximately 6 cases per 100 000[6][5]. In the UK ALS affects around two in every 100,000 people each year and at any one time there are about 5,000 people living with the condition.[7]

- For about half of those with the condition the mean life expectancy from onset of symptoms to death is 2-4 yrs

- Only 20% live beyond 5yrs

- 5% of those diagnosed had it before they were 47 years old

- Incidence peaks between 55 and 65 years of age

- Clinicians are reporting that they are seeing increasing numbers of younger ALS patients.

- Currently there is no cure for motor neurone disease.

Sporadic MND[edit | edit source]

- Sporadic ALS (90-95%) constitutes the large majority of cases[5]

- Most common in men[5]

- Yearly incidence is 1-2 per 100,000[6]

Familial MND[edit | edit source]

- Family history of either motor neurone disease or a related condition called frontotemporal dementia.[7]

- Autosomal dominant

- Ratio 1:1 (men to women)

- Mean age onset 47 years of age

- Represents 5-10% of all ALS occurrences[5]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The causes of ALS essentially unknown but several factors are thought to be involved including environmental risk factors,[8] Gene mutations have also been identified in some cases of ALS[6][8]

- Genetic – this is not true for all cases but some mutations have been identified in some individuals. In these cases, it is not uncommon to have several cases in one family.[7][9]

- Biochemistry – it appears that MND mainly occurs through the activation of calcium-dependant enzymatic pathways.

- Premature ageing of some motor cells may lead to damage and destruction if these cells. This then puts pressure on the surviving cells

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

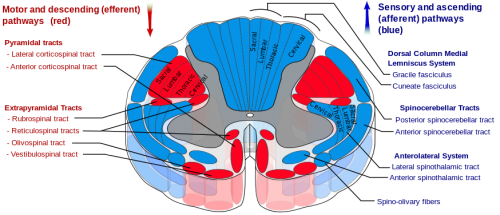

In the progression of the disease there is a loss of motor neurones from the anterior horn of the spinal cord, the primary motor cortex and from the hypoglossal nucleus in the lower medulla. Surrounding glial cells are also affected. Shrinkage and discolouration of the anterior nerve roots in the spinal cord occurs because of axonal degeneration of the neurones and the accompanying demyelination.[10]

The pathophysiology behind the disease appears to be multi-factorial with complex interactions between genetics and molecular pathways.[9]

Potential cellular & molecular mechanisms that contribute to the neuro degeneration of MND:[9]

• Abnormal mitochondria functioning

• Increased oxidative stress

• Increased free radicals

• Impaired axonal transport

• Sodium-potassium pump dysfunction

• Increased inflammatory mediators

• Increased toxin secretion

Potential gene mutations that are harmful to neurons and could contribute to the disease:[9]

• TARDBP

• FUS

Clinical Manifestations[edit | edit source]

Initial symptoms may be slight and go unnoticed. ALS may start with intermittent muscle twitching, weakness and in some cases slurred speech. The progression of ALS can also vary between individuals.[7][11]

Initial Symptoms- vary depending on were it first manifests[edit | edit source]

Limb-onset disease

- Weakened grip

- Weakness at shoulder

- Weakness at ankle or hip

- Widespread twitching of the muscles (fasciculations)

- Muscle cramps

- Visible wasting of the muscles with significant weight loss

Bulbar-onset disease

- Increasingly slurred speech (dysarthria)

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

Respiratory-onset disease[edit | edit source]

- Breathing difficulties

- Shortness of breath

- Waking up frequently during the night because the brain is temporarily starved of oxygen when lying down

Advanced Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Muscle weakness

- Muscle Atrophy

- Movement difficulty

- Spasticity

- Excess saliva from reduced swallowing

- Thicker saliva may sometimes be difficult to clear from the chest or throat due to weakening of muscles

- Excess yawning

- Emotionality

- Difficulties with concentration, planning and use of language

- Fronto-temporal dementia – this affects their ability to problem solve and respond to new situations[4]

- Breathing difficulties, such as shortness of breath

End-stage Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Increasing body paralysis

- Significant shortness of breath

Secondary Symptoms[edit | edit source]

These are not directly caused by the disease but are related to the stress of living with it.

- Depression

- Insomnia

- Anxiety

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There is no single test that diagnoses an individual with ALS[11]. However, several characteristics of the disease can be identified and therefore used to point practitioners in the right direction. El Escorial Criteria mentions the specific characteristics and features that need to be displayed in an individual for a proper ALS diagnosis; although they are not exclusive. It classifies diagnosis into four different categories depending on severity of upper (UMN) as well as lower motor neuron (LMN) degeneration (which must not be explained by the presence another neurological disorder). Physicians use a combination of a few methods such as electromyography and neuroimaging to identify UMN and LMN degeneration which is the most prominent feature in neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, current research is looking into whole-brain magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) as a source of determining disability levels in ALS in the future.

- With the exception of one genetic test, no definitive diagnostic test or biological marker exists for ALS – however, not all individuals with the disease present with this gene

- El Escorial Criteria for diagnosis of ALS (revised): [11]

The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) requires-

A - the presence of:

- evidence of lower motor neuron (LMN) degeneration by clinical, electrophysiological or neuropathologic examination,

- evidence of upper motor neuron (UMN) degeneration by clinical examination, and

- progressive spread of symptoms or signs within a region or to other regions, as determined by history or examination.

Together with:

B - the absence of:

- electrophysiological and pathological evidence of other disease processes that might explain the signs of LMN and/or UMN degeneration, and

- neuroimaging evidence of other disease processes that might explain the observed clinical and electrophysiological sign

Clinically Definite ALS; Clinical evidence alone by the presence of UMN, as well as LMN signs, in three regions.

Clinically Probable ALS; Clinical evidence alone by UMN and LMN signs in at least two regions with some UMN signs necessarily rostral to (above) the LMN signs.

Clinically Probable with Laboratory support ALS; Clinical signs of UMN and LMN dysfunction are in only one region, or when UMN signs alone are present in one region, and LMN signs defined by EMG criteria are present in at least two limbs, with proper application of neuroimaging and clinical laboratory protocols to exclude other causes.

Clinically Possible ALS: Clinical signs of UMN and LMN dysfunction are found together in only one region or UMN signs are found alone in two or more regions; or LMN signs are found rostral to UMN signs and the diagnosis of Clinically Probable – Laboratory supported ALS cannot be proven by evidence on clinical grounds in conjunction with electro diagnostic, neurophysiologic, neuroimaging or clinical laboratory studies.

Other diagnoses must have been excluded to accept a diagnosis of Clinically possible ALS.

Clinically Suspected ALS is a pure LMN syndrome, wherein the diagnosis of ALS could not be regarded as sufficiently certain to include the patient in a research study. Hence, this category is deleted from the revised El Escorial Criteria for the Diagnosis of ALS.)

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

There is increasing evidence that ALS should be regarded as a multisystem health condition rather than solely a motor disease. There is no cure or standard treatment for ALS so the focus is on supportive treatments that aim to maintain the individuals’ quality of life[7]. Treatment should take a holistic approach as the disease can be very distressing for the individual and their family and it is important not only to focus on the physical aspect of the disease but also the emotional and psychosocial components.[6]

Physiotherapy, respiratory and occupational therapy and social care are important in the care of those with ALS. Dieticians can help ensure that those with ALS eat a balanced diet and receive proper nutrition to help them maintain weight and keep up their strength as individuals can often lose weight as their ability to swallow is impaired. Dieticians can also advise patients as certain foods, such as dairy products could contribute to the production of thicker secretions.[4]

As the disease progresses breathing becomes increasingly difficult and the use of non-invasive ventilation can significantly improve the quality of life and may also increase the patient’s life expectancy by about 7 months.[12]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Because of the variable clinical presentation of people with ALS [PALS], the great variability in prognosis, and the typically rapid, progressive, and deteriorating nature of ALS, we as physical therapists are constantly challenged when developing the most appropriate intervention plan for PALS. The physical therapist needs an understanding of the nature and course of the disease, and needs to consider future problems in addition to current status. In order to make appropriate and effective decisions, the nature and significance of the activity limitations, and participation restrictions need to be determined. Decision-making involves determining which impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions: 1) can be restored; 2) require compensatory strategies or interventions; 3) require referral to different health care professional(s); and 4) cannot be affected by physical therapy interventions at all.[2]

Many of the problematic symptoms of ALS can be addressed by appropriate physical therapy interventions[2]

- fatigue (energy conservation)

- muscle stiffness (stretching exercises)

- muscle cramps (stretching exercises)

- pain (intervention dependent on source of pain)

Exercises should focus on improving posture, preventing joint immobility, and slowing the progressive muscle weakening and atrophy. Stretching and strengthening exercises may help reduce spasticity, increase range of motion and improve circulation.

Other modalities, such as heat application and massage may help relieve pain.

Assistive devices such as supports or braces, orthotics, speech synthesisers, and wheelchairs may help some people retain independence.

| [13] | [14] |

Current and Future Research[edit | edit source]

Research options fall largely into three categories: drugs, gene therapy, and stem cells.[9]

Clinical trials are testing whether different drugs or interventions are safe and effective in slowing the progression of ALSs in patient volunteers.

Cellular and molecular studies seek to understand the mechanisms that trigger motor neurons to degenerate.[6]

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Overview of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Dr. Leo McCluskey provides an overview of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at the February 2012 FTD Caregiver Conference, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vijayakumar UG, Milla V, Stafford C, Bjourson T, Duddy WJ, Duguez SR. A systematic review of suggested molecular strata, biomarkers and their tissue sources in ALS. Frontiers in neurology. 2019;10:400. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00400/full (last accessed 14.12.2019)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Dal Bello-Haas V. Physical therapy for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: current insights. Degenerative neurological and neuromuscular disease. 2018;8:45. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6065609/ (last accessed 14.12.2019)

- ↑ Neuroscientifically Challenged ALS Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOnk9Hh20eg&app=desktop (last accessed 14.12.2019)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Marsden, R. Motor neurone disease: an overview. Primary Health Care 2011; 21;10;31-36 (Accessed 18th May 2015)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Talbott EO, Malek AM, Lacomis D. The epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In Handbook of clinical neurology 2016 Jan 1 (Vol. 138, pp. 225-238). Elsevier.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. . Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Fact Sheet, NINDS, Publication date June 2013.NIH Publication No. 16-916 (Accessed 23rd April 2019)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 NHS Information http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Motor-neurone-disease/Pages/Symptoms.aspx (accessed April 28th at 11:49)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Martin S, Al Khleifat A, Al-Chalabi A. What causes amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?. F1000Research. 2017;6.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Kiernan, M.C., Vucic, S., Cheah, B.C., Turner, M.R., Eisen, A., Hardiman, O., Burrell, J.R., Zoing, M.C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2011; 377; 942-55 http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2810%2961156-7/abstract (accessed 4th May 2015)

- ↑ Jeans, A.F., Ansorge, O. Recent developments in the pathology of Motor Neurone Disease. Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation; Neuropathology Article 2009; 9; 4; 25-26 http://www.acnr.co.uk/SO09/ACNRSO09_web.pdf (Accessed 4th May 2015)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 ALS Association. Factsheet: Criteria for the diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology. http://www.alsa.org/assets/pdfs/fyi/criteria_for_diagnosis.pdf (Accessed 4 May 2015).

- ↑ Gent, C. Understanding motor neurone disease. Nursing and Residential Care 2013; 14;12; 646-649. http://dx.doi.org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/10.12968/nrec.2012.14.12.646 (Accessed 18th May 2015).

- ↑ Weyton Tam. Seeking ALS Answers: Range of Motion Therapy. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=myoazlf9pdc [last accessed 15/01/16]

- ↑ maremmagirl. ALS/MND Right Shoulder Massage. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28Bv3-DZq5g [last accessed 15/01/16]