Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Original Editors

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases: CINAHL, Cochrane, Medline with Full Text, PubMed, ScienceDirect, GoogleScholar, EBSCO, ProQuest

Search Terms: cubital tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve entrapment, compression, medial elbow pain, ulnar elbow pain, nerve entrapment, ulnar nerve, surgery, conservative treatment, rehabilitation, compression injury of upper extremity, coppieters, anterior transposition of ulnar nerve, ulnar nerve decompression, tardy ulnar neuritis, ulnar nerve glide, osborne, neurodynamics

Search Timeline: September 19, 2010 – November 22, 2010

Definition/Description

[edit | edit source]

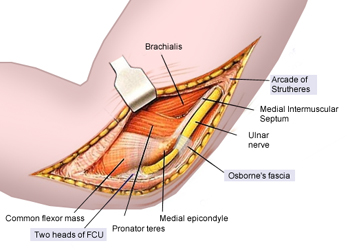

Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow. The ulnar nerve, which is a motor and sensory nerve, is formed from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, which originates from nerve roots C8 and T1.[1][2][3] The ulnar nerve travels down the posterior aspect of the arm to eventually traverse posterior to the medial epicondyle through an area known as the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the olecranon process of the ulna.[4] The nerve runs superficial to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and deep to the aponeurotic attachment of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is also known as Osborne’s ligament. Once the ulnar nerve reaches the proximal border of Osborne’s ligament it is located in the cubital tunnel.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most commonly reported upper extremity entrapment neuropathy and is the most common ulnar nerve neuropathy.[5][6] Risk factors include: head injuries with upper extremity flexion contractures, age > 40, overhead throwers, work that involves prolonged periods of elbow flexion such as holding a telephone, and resting elbows on a hard surface.[3][7][8] Entrapment can occur at multiple levels in the cubital tunnel including: the Arcade of Struthers, the medial intermuscular septum, the medial epicondyle, Osborne's ligament and the flexor-pronator aponeurosis.[9] It may be a result of direct or indirect trauma and is vulnerable to traction, friction, and compression. Traction injuries may be the result of longstanding valgus deformity and flexion contractures, but are most common in throwers due to extreme valgus stress placed on the arm.[10] Compression of the nerve at the cubital tunnel may occur due to reactive changes at the UCL, adhesions within the tunnel, hypertrophy of the surrounding musculature, or joint changes.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

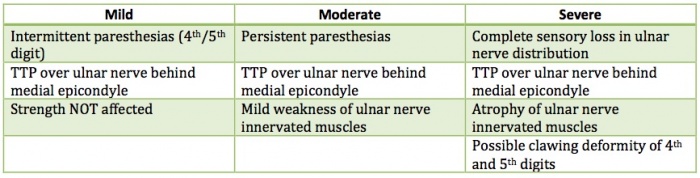

Depending on the duration and progression of the disorder, patients with cubital tunnel syndrome will present with similar but specific symptoms (see Table 1).[5] The most common complaint for any cubital tunnel syndrome patient is paresthesias in the 4th and 5th digits that often wakes them at night.[3] The patient may also report non-painful "snapping" or "popping" during active and passive flexion and extension of the elbow and a Wartenberg sign (abduction of the fifth digit due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle) may also be present. Patients may also notice weakness while pinching, occasional clumsiness, and a tendency to drop things.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here

Examination[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

With CBTS being the most common ulnar nerve neuropathy and the 2nd most common upper extremity neuropathy, early detection through proper differential diagnosis is key to ensuring best possible patient outcomes. As skilled clinicians we must tailor our treatment to each patient, post-surgical or not, in a manner that follows surgeon precautions if necessary and aims to normalize the sensitivity of the nerve, restore normal nerve biomechanics, and restores or prevents secondary complications. With insufficient quality evidence to support conservative management of cubital tunnel syndrome, we need more randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of current treatment trends.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar nerve palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78:351.

- ↑ Osborne GV. The surgical treatment of tardy ulnar neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39B:782.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Tetro AM, Pichora DR. Cubital tunnel syndrome and the painful upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):665-677.

- ↑ Wheeless CR. Cubital tunnel syndrome. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/cubital_tunnel_syndrome. Updated June 5, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Coppieters MW, Bartholomeeusen KE, Stappaerts KH. Incorporating nerve-gliding techniques in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2004;27(9):560-568.

- ↑ Kuschner SH, Ebramzadeh E, Mitchell S. Evaluation of elbow flexion and tinel tests for cubital tunnel syndrome in asymptomatic individuals. Orthopedics. 2006;29(4):305-308.

- ↑ Bartels RHMA, Verbeek ALM. Risk factors for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: a case control study. Acta Neurochir Wien. 2007;149:669-674.

- ↑ Oskay D, Meriç A, Kirdi N, Firat T, Ayhan Ç, Leblebicioglu G. Neurodynamic mobilization in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: long-term follow-up of 7 cases. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2010;33(2):156-163.

- ↑ Husain SN, Kaufmann RA. The diagnosis and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2008;19(5):470-474.

- ↑ Lee ML, Rosenwasser MP. Chronic elbow instability. Orthop Coin North Am. 1999;30:81-89.

- ↑ ASSH. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. http://www.assh.org/Public/HandConditions/Pages/CubitalTunnelSyndrome.aspx. Accessed November 1, 2010.