Promoting Active Living in Young People Through Behaviour Change

Original Editors - Add your name/s here if you are the original editor/s of this page.

Top Contributors - Ronan Mac Cann, Lee Pettett, Sammy Anjum, Arden Metford, Kim Jackson, Lee Krol, Lucinda hampton, Rucha Gadgil, Rachael Lowe and Brian McGowan

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

How to use the resource pack[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Background[edit | edit source]

What is Active Living?[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Epidemiology physical activity and sedentary behavior:[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Justification for the emerging role within Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Economic implications of physical inactivity[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Benefits of physical activity in young people:[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Barriers and facilitators to physical activity:[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Ethical considerations when working with young people[edit | edit source]

- Government Legislation and Policies For Working with Young People

- Getting it Right for Every Child

- Ready to Act Plan

-Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014

- Safeguarding Young People

- Informed Consent

- Confidentiality

Knowledge and understanding of relevant legal frameworks, including local policies are essential for Physiotherapists who work with young people to ensure they work effectively and deliver services appropriately (LP 1).

Getting it Right for Every Child

Central to the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5), is the ‘Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)’ policy (LP 6). This policy states that all adults working with children and young people should ensure their actions support the best interest of children and young people through promoting, supporting and safeguarding wellbeing and reporting on wellbeing outcomes (LP 10)

- GIRFEC is a key part of the Scottish Government’s commitment to addressing inequalities and improving outcomes for children and the young through early intervention and prevention (LP 11)

- GIRFEC is underpinned by the recognised need for shared principles and values and a common language among practitioners who provide services for children and families (LP 12).

- GIRFEC is intended to be used by health practitioners to gather information about a child’s well-being to identify concerns and determine what support and action may be needed (LP 10)

The GIRFEC approach:

- Integrated Working: focuses on children, young people, parents and services they need working together in a coordinated way to meet the specific needs and to improve overall well-being.

- Child Focused: ensures the child or young person (and their family) are at the centre of decision-making and have appropriate support available to them.

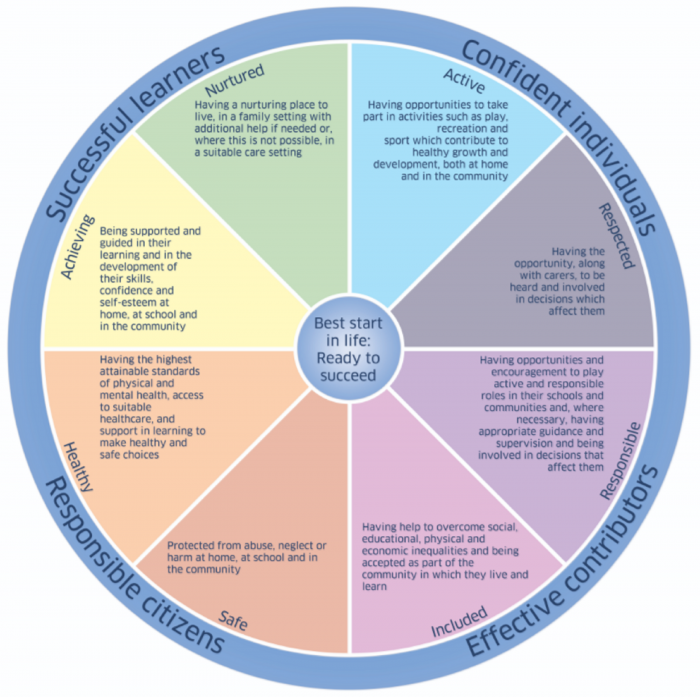

- Well-being of children: focuses on a child or young person’s overall well-being such as how safe, healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible and included.

- Early Interventions: focuses on tackling the needs of a child and young person early, aiming to ensure the needs are identified as early as possible to avoid larger concerns and problems to develop.

The well-being of children and young people is at the heart of GIRFEC (LP 11) The approach uses eight areas of well-being, SHANARRI indicators, which represent the basic requirements for all children and young people to grow and develop and reach their full potential. The eight indicators are illustrated in below in the well-being wheel of GIRFEC (LP 6).

Ready to Act Plan:

The Ready to Act Plan (LP2) delivers one of the actions from the AHP National Delivery Plan, where allied health professionals (AHPs) act as Agents of Change in Health and Social Care (LP 3). Ready to Act (LP2) will contribute to the developing Active and Independent Living Improvement Programme (LP 4). The plan sets out five key ambitions for AHP services for young people based on the outcomes young people, their parents, carers, families and stakeholders reported that mattered to their lives. The key ambitions are illustrated in the table below:

** insert excel sheet here.

The Ready to Act Plan (LP 2) is the first children and young people’s services plan in Scotland to focus on the support provided by AHPs. The plan sets the direction of travel for the design and delivery of AHP services to meet the well-being needs of young people. It is underpinned by the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5), the principles of Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) (LP 6) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (LP 7).

Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014:

The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 (LP 5) establishes a legal framework within which services create new and dynamic partnerships to support young people, their parents, carers and families to achieve meaningful wellbeing outcomes (LP 1, LP8). These outcomes include what has come to be known as the SHANARRI indicators of well-being. AHPs, including Physiotherapists, play a key role in young people achieving well-being outcomes through developing their resilience and creating protective environments to enable participation and self-reliance (LP 9).

**Summary of area to be inserted into here **

Safeguarding Young People:

Safeguarding is a term which is broader than ‘child protection’ and relates to the action taken to promote the welfare of children and protect them from harm (LP 1). Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility.

Safeguarding is defined in Working together to Safeguard Children 2015 (LP 13) as:

- Protecting children and young people from maltreatment

- preventing impairment of children’s and young people’s health and development

- Ensuring that children and young people grow up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care and

- Taking action to enable all children and young people to have the best outcomes

In order to safeguard and promote the welfare of children in Scotland, Physiotherapists should act in accordance with the following legislation and guidance:

- Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (LP 16)

- Protection from Abuse (Scotland) Act 2001 (LP 17)

- Protection of Children and Prevention of Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2005 (LP 18)

- Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007 (LP 19)

- Children and Young People (Scotland) 2014 (LP 5)

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NCPPC) (LP 20) offer links to the following documents for advice and guidance for health practitioners with concerns for children and young people:

- What to do if you’re worried a child is being abused: advice for practitioners (LP 21)

- Safeguarding children and young people from sexual exploitation (LP 22)

- Safeguarding children in whom illness is fabricated or induced (LP 23)

*** need to work out how to hyperlink the above websites to the associated text.

** Summary of what Physios need to know about Safeguarding

Informed Consent:

The position on consent in relation to children is complex (LP 20). It is important for Physiotherapists working with children to be familiar with literature, statutes, case law, professional guidance and department of health guidance on the ethical and legal aspects of children and young people’s consent (LP 1). The issue regarding capacity is of particular importance when dealing with children (LP 25). The law recognises broadly three stages of childhood with respect to consent:

- Children and young people who lack capacity- If the child does not have the capacity to give their own consent e.g. they are too young or do not understand fully what is involved, then a parent/ person with parental responsibility, or the Court, may give consent on the child’s behalf (LP 1)

- Children and young people with capacity: A child under 16 who has the capacity to make their own decisions may be referred to as ‘Gillick competent’ after the legal case that established children can make their own decisions in certain circumstances (LP 26).

- Children and young people over the age of 16: All 16-17 year olds with capacity are permitted by law to give their own consent to health interventions. (LP 27) Those children who are 16 or over on the date they attend for treatment do not need parental consent for Physiotherapy (LP 1). You should not share confidential information about 16-17 year olds with their parents, or others, unless you have specific permission to do so and/or you are legally obliged to.

According to Scottish law, children over the age of 12 are usually considered to be sufficiently mature to form a view and can have the legal capacity to consent to health interventions where in the opinion of a qualified health practitioner, the child is capable of understanding the nature and possible consequences of the intervention (LP 28)

This is a matter of clinical judgement and will depend on several things, including (LP 1):

- The age of the patient

- The maturity of the patient

- The complexity of the proposed intervention

- The likely outcome of the intervention

- The risks associated with the intervention

If the child or young person is not capable of understanding the nature of the healthcare intervention and its consequences, it is then advised to contact the child’s parent or guardian for consent to proceed with the intervention (LP 29). Although a young person is deemed capable of giving consent independently, it is still highly encouraged to seek consent from both the young person and their parents or guardians (LP 30; LP 31)

Confidentiality:

Confidentiality is of fundamental importance to young people as outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (LP 7). Young people have the same rights to confidentiality as adults, however the duty to safeguard young people should come first (LP 32, LP 33, LP 44). When obtaining consent, confidentiality needs to be explained to young people in terms that they understand and that they are aware of events in which the Physiotherapist may be required to act on concerning information and pass it on to relevant organisations (LP 36). In addition, parents of young people may request access to the young person’s responses after undertaking a health intervention questionnaire or survey. There are strong ethical reasons why parents should not have access to what their child says on a questionnaire as young children may be harmed, embarrassed or punished based on the responses they have given (LP 37). Rather than giving parents access to responses, it may be beneficial to offer parents to view the questionnaire prior to it being completed (LP37) or to encourage parents to initiate discussions about the questionnaire with their children in a home setting (LP 38).

Current government strategies[edit | edit source]

The Scottish government was one of the first countries in the world to release a national physical activity strategy, by providing a broad framework and implementation plan, called Lets makes Scotland more active in 2003. (LK 5)

This 20 year strategy’s five year review acknowledged there had been progress made with the populations physical activity levels. It has been followed up more recently after the 2014 commonwealth games with the strategy A more active Scotland. (LK 6) This is an adaptation of the Toronto Charter for Physical Activity (2010) which is a gold standard tool. (LK 7)

When specifically looking at young people, the strategies aim is to create a long lasting change in physical activity levels through:

Communities services and facilities:

- More children will have opportunities for active and outdoor play

- More children will routinely take part in play, sport, or other forms of active recreation

- More children will have opportunities for active and outdoor play

- Urban and rural environments will be designed to increase physical activity

- 20 mph zones will be widely introduced in residential and shopping areas

Schools:

- Education staff have the appropriate knowledge and skills to promote increased physical activity

- All places of learning can demonstrate the use of their estate and green space for physical activity

- All places of learning can demonstrate that pupils, students and staff have increased levels of physical activity

- More children and students use active travel to get to their places of learning

This was to be achieved through legacies where it was reported over 50 had been launched at their in 2015 review. Legacies are part of the implementation plan, an example includes is a national week was held encouraging more women and girls into sport as females have been found to be less active than males (LK 8). The statistics also show young peoples physical activity have slightly increased both including and excluding the increased physical activity in schools. It is still, however, unclear the prevalence rate transferring onto a long-term active lifestyle as the adult physical activity level has not increased.

Health-Related Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Models of behaviour change[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Method for measuring physical activity[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

IPAQ-SF modified scoring system[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Behavioural change progression[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Motivational interviewing[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.