Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

== Examination<br> == | == Examination<br> == | ||

The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list and examination should be individualized to the patient. | The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list and examination should be individualized to the patient. <br>History[15]<br>• Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs/symptoms have affected his/her function. <br>- Type of symptoms <br>- Location and amplitude of symptoms <br>- Irritability of symptoms <br>- Onset and development over time <br>- Aggravating/alleviating factors <br>- Disability<br>Physical Examination[15][16] <br>• Observation<br>- Posture <br>- Cyanosis <br>- Edema <br>- Paleness <br>- Atrophy <br>• Palpation <br>- Temperature changes <br>- Supraclavicular fossa<br>- Scalene muscles (tenderness)<br>- Trapezius muscle (tenderness)<br>• Neurological Screen | ||

'' | <br>• MMT & Flexibility of following muscles: <br>- Scalene <br>- Pectoralis major/minor <br>- Levator scapulae <br>- Sternocleidomastoid <br>- Serratus anterior <br>Special Tests[2][16] <br>• Elevated Arm Stress/ Roos test: the patient has arms at 90° abduction and the therapist puts downwards pressure on the scapula as the patient opens and closes the fingers. If the TOS symptoms are reproduced within 90 seconds, the test is positive. [24]<br>• Adson's: the patient is asked to rotate the head and elevate the chin toward the affected side. If the radial pulse on the side is absent or decreased then the test is positive, showing the vascular component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed by the scalene muscle or cervical rib. [24]<br>• Wright's: the patient’s arm is hyper abducted. If there is a decrease or absence of a pulse on one side then the test is positive, showing the axillary artery is compressed by the pectoralis minor muscle or coracoid process due to stretching of the neurovascular bundle. [24]<br>• Cyriax Release: the patient is seated or standing. The examiner stands behind patient and grasps under the forearms, holding the elbows at 80 degrees of flexion with the forearms and wrists in neutral. The examiner leans the patient’s trunk posteriorly and passively elevated the shoulder girdle. This position is held for up to 3 minutes. The test is positive when paresthesia and/or numbness (release phenomenon) occurs, including reproduction of symptoms. (Hooper et. al., 2010 & Brismee et. al., 2004)<br>• Supraclavicular Pressure: the patient is seated with the arms at the side. The examiner places his fingers on the upper trapezius and thumb on the anterior scalene muscle near the first rib. Then the examiner squeezes the fingers and thumb together for 30 seconds. If there is a reproduction of pain or paresthesia the test is positive, this addresses compromise to brachial plexus through scalene triangles. (Hooper et al., 2010)<br>• Costoclavicular Maneuver: this test may be used for both neurological and vascular compromise. The patient brings his shoulders posteriorly and hyperflexes his chin. A decrease in symptoms means that the test is positive and that he neurogenic component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed. [24]<br>• Upper Limb Tension: These tests are designed to put stress on neurological structures of upper limb. The shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist and fingers are kept in specific position to put stress on particular nerve (nerve bias) and further modification in position of each joint is done as "sensitizer". (http://www.physio-pedia.com/Neurodynamic_Assessment)<br>• Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion: The test is performed with the patient in sitting. The cervical spine is passively and maximally rotated away from the side being tested. While maintaining this position, the spine is gently flexed as far as possible moving the ear toward the chest. A test is considered positive when the lateral flexion movement is blocked. | ||

Test Sensitivity Specificity LR+ LR- <br>Elevated Arm Stress 52-84% 30-100% 1.2-5.2 0.4-0.53 <br>Adson's 79% 74-100% 3.29 0.28 <br>Wright's 70-90% 29-53% 1.27-1.49 0.34-0.57 <br>Cyriax Release NT 77-97% NA NA <br>Supraclavicular Pressure NT 85-98% NA NA <br>Costoclavicular Maneuver NT 53-100% NA NA <br>Upper Limb Tension 90% 38% 1.5 0.3 <br>Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion 100% NT NA NA | |||

• Electrodiagnostic evaluation and imaging <br>Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are often helpful as components of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected TOS. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal decreased ulnar sensorial potentials, decreased median action potentials, normal or close to normal ulnar motor and median sensorial potentials (Huang and Zager 2004). Vascular TOS can be identified with venography and arteriography. <br>Besides the electrophysiological studies, imaging studies can provide useful information in the diagnosis of TOS. Cervical spine and chest x-rays are important in the identification of bony abnormalities (such as cervical ribs or a “peaked C7 transverse processes)<br><br> | |||

<br> | |||

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are often helpful as components of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected TOS. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal decreased ulnar sensorial potentials, decreased median action potentials, normal or close to normal ulnar motor and median sensorial potentials (Huang and Zager 2004). Vascular TOS can be identified with venography and arteriography. Besides the electrophysiological studies, imaging studies can provide useful information in the diagnosis of TOS. Cervical spine and chest x-rays are important in the identification of bony abnormalities (such as cervical ribs or a “peaked C7 transverse processes) | |||

== Medical Management <br> == | == Medical Management <br> == | ||

Revision as of 10:41, 18 June 2016

Original Editors - Chelsey Walker, Jacqueline Keller, Katie Schwarz, Jenny Nordin, Chris Slininger as part of the Texas State University Evidence-based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Alicia Fernandes

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

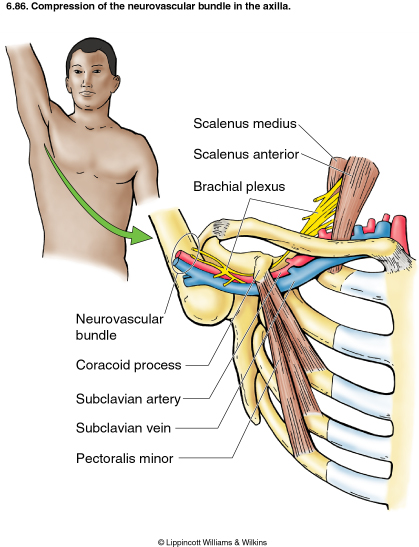

The term ‘thoracic outlet syndrome’ describes compression of the neurovascular structures as they exit through the thoracic outlet (cervicothoracobrachial region). The thoracic outlet is marked by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene posteriorly, and the first rib inferiorly. [25][26]

This condition has emerged as one of the most controversial topics in musculoskeletal medicine and rehabilitation [2]. This controversy extends to almost every aspect of the pathology including the definition, incidence, pathoanatomical contributions, diagnosis, and treatment.

The term ‘TOS’ does not specify the structure being compressed. Investigators namely identify two main categories of TOS: the vascular form (arterial or venous), which raises few diagnostic problems, and the neurological form, which occurs in more than 95-99% of all cases of TOS. Therefore the syndrome should be differentiated by using the terms arterial TOS (ATOS), venous TOS (VTOS) or neurogenic (NTOS). [25][26]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The first narrowing area is the most proximal and is named the interscalene triangle: This triangle is bordered by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene muscle posteriorly, and the medial surface of the first rib inferiorly. The presence of the scalene minimus muscle and the fact that both the anterior and middle scalene muscles have their insertion in the first rib (which can cause overlapping) can cause a narrow space and therefore compression . The brachial plexus and the subclavian artery pass through this space.

The second passageway is called the costoclavicular triangle which is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula. The subclavian vein, artery and plexus brachialis crosses this costoclavicular region and then further enters the subcoracoïd space. Just distal to the insterscalene triangle. Compression of these structures can occur as a result of congenital abnormalities, trauma to the first rib or clavicle, and structural changes in the subclavian muscle or the costocoracoid ligament.

The last passageway is called the subcoracoid or sub-pectoralis minor space: This last passageway is beneath the coracoid process just under the pectoralis minor tendon. The borders of the thoraco-coraco-pectoral space include the coracoid process superiorly, the pec minor anteriorly, and ribs 2-4 posteriorly. Shortening of the pectoralis minor can lead to a narrowing of this last space and therefore compression of the neurovascular structures during hyperabduction. [3][24][26]

Certain anatomical abnormalities can be potentially compromising to the thoracic outlet as well. These include the presence of a cervical rib, congenital soft tissue abnormalities, clavicular hypomobility [2], and functionally acquired anatomical changes [3]. Soft tissue abnormalities may create compression or tension loading of the neurovascular structures found within the thoracic outlet (such as hypertrophy , a broader middle scalene attachment on the 1st rib or fibrous bands that increase the stiffness,…).

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

TOS affects approximately 8% of the population and is 3-4 times as frequent In woman as in men between the age of 20 and 50 years. Females have less-developed muscles, a greater tendency for drooping shoulders owing to additional breast tissue, a narrowed thoracic outlet and an anatomical lower sternum, these factors change the angle between the scalene muscles and consequently cause a higher prevalence in women.[3][16] [24] The mean age of people effected with TOS is 30s-40s; it is rarely seen in children. Almost all cases of TOS (95-98%) affect the brachial plexus; the other 2-5% affecting vascular structures, such as the subclavian artery and vein.

There are several factors which can cause TOS: Cervical ribs are present in approximately 0.5-0.6% of the population, 50-80% of which are bilateral, and 10-20% produce symptoms; the female to male ratio is 2:1. Cervical ribs and the fibromuscular bands connected to them are the cause of most neural compression. [8] Fibrous bands are a more common cause of TOS than rib anomalies.

Congenital factors:

• Cervical rib[4][9][10]

• Prolonged transverse process

• Anomalous muscles

• Fibrous anomalies (transversocostal, costocostal)

• Abnormalities of the insertion of the scalene muscles [4]

• Fibrous muscular bands[4]

• Exostosis of the first rib

• Cervicodorsal scoliosis[11]

• Congenital uni- or bilateral elevated scapula

• Location of the A. or V. Subclavian in relation to the M. scalene anterior

Acquired conditions:

• Postural factors

• Dropped shoulder condition[4][12]

• Wrong work posture (standing or sitting without paying attention to the physiological curvature of the spine)

• Heavy mammaries

• Trauma[11]

• Clavicle fracture[4]

• Rib fracture[4]

• Hyperextension neck injury, whiplash[6][9]

• Repetitive stress injuries (repetitive injury most often form sitting at a keyboard for long hours)[6]

Muscular causes:

• Hypertrophy of the scalene muscles

• Decrease of the tonus of the M. trapezius, M. levator scapulae, M.rhomboids

• Shortening of the scalene muscles, M. trapezius, M. levator scapulae, pectoral muscles

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome vary from patient to patient due to the location of nerve and/or vessel involvement. Symptoms range from mild pain and sensory changes to limb threatening complications in severe cases.

Patients with thoracic outlet syndrome will most likely present pain anywhere between the neck, face and occipital region or into the chest, shoulder and upper extremity and paresthesia in upper extremity. The patient may also complain of altered or absent sensation, weakness, fatigue, a feeling of heaviness in the arm and hand. The skin can also be blotchy or discolored. A different temperature can also be observed.

Signs and symptoms are typically worse when the arm is abducted overhead and externally rotated with the head rotated to the same or the opposite side. As a result activities such as overhead throwing, serving a tennis ball, painting a ceiling, driving, or typing may exacerbate symptoms. [21][23]

When the upper plexus (C5,6,7) is involved there is pain in the side of the neck and this pain may radiate to the ear and face. Often the pain radiates from the ear posteriorly to the rhomboids and anteriorly over the clavicle and pectoralis regions. The pain may move laterally down the radial nerve area. Headaches are not uncommon when the upper plexus is involved.

Patients with lower plexus (C8,T1) involvement typically have symptoms which are present in the anterior and posterior shoulder region and radiate down the ulnar side of the forearm into the hand, the ring and small fingers. [24][2]

There are four categories of thoracic outlet syndrome and each presents with unique signs and symptoms (see Table 1). Typically TOS does not follow a dermatomal or myotomal pattern unless there is nerve root involvement, which will be important in determining your PT diagnosis and planning your treatment [2][3].

| Arterial TOS | Venous TOS | True TOS | Disputed Neurogenic TOS |

|

|

|

|

Compressors* - a patient that experiences symptoms throughout the daytime while using prolonged postures resulting in increased tension or compression of the thoracic outlet

Releasers* - a patient that experiences a release phenomenon (release of tension or compression to thoracic outlet) that often awakes them at night

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Due the it's variability, TOS can be difficult to tease out from other pathologies with similar presentations. A thorough history and evaluation must be done to determine if the patient’s symptoms are truly TOS. The following pathologies are common differential diagnosis for TOS[13][14]:

• Carpal tunnel syndrome

• De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

• Lateral epicondylitis

• Medial epicondylitis

• Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS I or II).

• Horner’s Syndrome

• Raynaud’s disease

• Cervical disease (especially discogenic)

• Brachial plexus trauma

• Systemic disorders: inflammatory disease, esophageal or cardiac disease

• Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis (UEDVT), Paget-Schroetter syndrome

• Rotator cuff pathology

• Glenohumeral joint instability

• Nerve root involvement

• Malignancies (local tumours)

• Chest pain, angina

• Vasculitis

• Thoracic 4 syndrome

• Sympathetic-mediated pain

Systematic causes of brachial plexus pain include:

• Pancoast’s Syndrome

• Radiation induced brachial plexopathy

• Parsonage Turner Syndrome [2][3]

There are conditions that can coexist with TOS. It is important to identify these conditions because they should be treated separately. These associated conditions include:

• carpal tunnel syndrome

• peripheral neuropathies (like ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow, shoulder tendinitis and impingement syndrome)

• fibromyalgia of the shoulder and neck muscles

• cervical disc disease (like cervical spondylosis and herniated cervical disk)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

DASH (Disability of Arm Shoulder and Hand)

SPADI (Shoulder Pain And Disability Index)

NPRS (Numeric Pain Rating Scale)

Examination

[edit | edit source]

The following includes common examination findings seen with TOS that should be evaluated; however, this is not an all-inclusive list and examination should be individualized to the patient.

History[15]

• Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs/symptoms have affected his/her function.

- Type of symptoms

- Location and amplitude of symptoms

- Irritability of symptoms

- Onset and development over time

- Aggravating/alleviating factors

- Disability

Physical Examination[15][16]

• Observation

- Posture

- Cyanosis

- Edema

- Paleness

- Atrophy

• Palpation

- Temperature changes

- Supraclavicular fossa

- Scalene muscles (tenderness)

- Trapezius muscle (tenderness)

• Neurological Screen

• MMT & Flexibility of following muscles:

- Scalene

- Pectoralis major/minor

- Levator scapulae

- Sternocleidomastoid

- Serratus anterior

Special Tests[2][16]

• Elevated Arm Stress/ Roos test: the patient has arms at 90° abduction and the therapist puts downwards pressure on the scapula as the patient opens and closes the fingers. If the TOS symptoms are reproduced within 90 seconds, the test is positive. [24]

• Adson's: the patient is asked to rotate the head and elevate the chin toward the affected side. If the radial pulse on the side is absent or decreased then the test is positive, showing the vascular component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed by the scalene muscle or cervical rib. [24]

• Wright's: the patient’s arm is hyper abducted. If there is a decrease or absence of a pulse on one side then the test is positive, showing the axillary artery is compressed by the pectoralis minor muscle or coracoid process due to stretching of the neurovascular bundle. [24]

• Cyriax Release: the patient is seated or standing. The examiner stands behind patient and grasps under the forearms, holding the elbows at 80 degrees of flexion with the forearms and wrists in neutral. The examiner leans the patient’s trunk posteriorly and passively elevated the shoulder girdle. This position is held for up to 3 minutes. The test is positive when paresthesia and/or numbness (release phenomenon) occurs, including reproduction of symptoms. (Hooper et. al., 2010 & Brismee et. al., 2004)

• Supraclavicular Pressure: the patient is seated with the arms at the side. The examiner places his fingers on the upper trapezius and thumb on the anterior scalene muscle near the first rib. Then the examiner squeezes the fingers and thumb together for 30 seconds. If there is a reproduction of pain or paresthesia the test is positive, this addresses compromise to brachial plexus through scalene triangles. (Hooper et al., 2010)

• Costoclavicular Maneuver: this test may be used for both neurological and vascular compromise. The patient brings his shoulders posteriorly and hyperflexes his chin. A decrease in symptoms means that the test is positive and that he neurogenic component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed. [24]

• Upper Limb Tension: These tests are designed to put stress on neurological structures of upper limb. The shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist and fingers are kept in specific position to put stress on particular nerve (nerve bias) and further modification in position of each joint is done as "sensitizer". (http://www.physio-pedia.com/Neurodynamic_Assessment)

• Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion: The test is performed with the patient in sitting. The cervical spine is passively and maximally rotated away from the side being tested. While maintaining this position, the spine is gently flexed as far as possible moving the ear toward the chest. A test is considered positive when the lateral flexion movement is blocked.

Test Sensitivity Specificity LR+ LR-

Elevated Arm Stress 52-84% 30-100% 1.2-5.2 0.4-0.53

Adson's 79% 74-100% 3.29 0.28

Wright's 70-90% 29-53% 1.27-1.49 0.34-0.57

Cyriax Release NT 77-97% NA NA

Supraclavicular Pressure NT 85-98% NA NA

Costoclavicular Maneuver NT 53-100% NA NA

Upper Limb Tension 90% 38% 1.5 0.3

Cervical Rotation Lateral Flexion 100% NT NA NA

• Electrodiagnostic evaluation and imaging

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are often helpful as components of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected TOS. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal decreased ulnar sensorial potentials, decreased median action potentials, normal or close to normal ulnar motor and median sensorial potentials (Huang and Zager 2004). Vascular TOS can be identified with venography and arteriography.

Besides the electrophysiological studies, imaging studies can provide useful information in the diagnosis of TOS. Cervical spine and chest x-rays are important in the identification of bony abnormalities (such as cervical ribs or a “peaked C7 transverse processes)

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been prescribed to reduce pain and inflammation. Botulinum injections to the anterior and middle scalenes have also found to temporarily reduce pain and spasm from neurovascular compression, further research is needed because there are discrepancies in the literature. Surgical management of TOS should only be considered after conservative treatment has been proven ineffective.

However, limb-threatening complications of vascular TOS have been indicated for surgical intervention. Surgery to treat thoracic outlet syndrome, may be performed using several different approaches, including: transaxillary approach, supraclavicular approach and infraclavicular approach.

- Transaxillary approach. The first rib forms the common denominator for all causes of nerve and artery compression in this region, so that its removal generally improves symptoms. Surgeon makes an incision in the chest to access the first rib, divide the muscles in front of the rib and remove a portion of the first rib to relieve compression, without disturbing the nerves or blood vessels.

- Supraclavicular approach has been advocated to perform first rib resection and scalenectomy, a safe and effective procedure, characterized by a shorter operative time and having a complication rate lower or comparable to that of transaxillary first rib resection. This approach repairs compressed blood vessels. The surgeon makes an incision just under the neck to expose the brachial plexus region. Then he looks for signs of trauma or muscles contributing to compression near the first rib. The first rib may be removed if necessary to relieve compression.

- Infraclavicular approach. In this approach, the surgeon makes an incision under the collarbone and across the chest. This procedure may be used to treat compressed veins that require extensive repair.

Neurogenic TOS: Surgical decompression should be considered for those with true neurological signs or symptoms. These include weakness, wasting of the hand intrinsic muscles, and conduction velocity less than 60 m/sec. The first rib can be a major contributor to TOS. There is controversy, however, regarding the necessity of a complete resection to reduce the chance of reattachment of the scalenes, scar tissue development, or bony growth of the remaining tissue. In addition to the first rib, cervical ribs are removed, scalenectomies can be performed, and fibrous bands can be excised.

Arterial TOS: Decompression can include cervical and/or first rib removal and scalene muscle revision. The subclavian can then be inspected for degeneration, dilation, or aneurysm. Saphenous vein graft or synthetic prosthesis can then be used if necessary.

Venous TOS: Thrombolytic therapy is the first line of treatment for these patients. Because of the risk of recurrence, many recommend removal of the first rib is necessary even when thrombolytic therapy completely opened the vein. The results of a study show that infraclavicular approach is a safe and effective treatment for acute VTOS. They had no brachial plexus or phrenic nerve injuries.Angioplasty can then be used to treat those with venous stenosis.

In venous or arterial TOS, medication can be administered to dissolve blood clots prior to thoracic outlet compression. It may also be to conduct a procedure to remove a clot from the vein or artery or repair the vein or artery prior to thoracic outlet decompression.

Some larger-chested women have sagging shoulders that increase pressure on the neurovascular structures in the thoracic outlet. A supportive bra with wide and posterior-crossing straps can help reduce tension. Extreme cases may resort to breast-reduction surgery to relieve TOS and other biomechanical problems.

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Conservative management should be the first strategy to treat TOS since this seems to be effective at decreasing symptoms, facilitating return to work and improving function, but yet a few studies have evaluated the optimal exercise program as well as the difference between a conservative management and no treatment.[36] Level of evidence 1A Conservative management includes physical therapy, which focuses on patient education, paincontrol, range of motion, nerve gliding techniques, strengthening and stretching. [37] Level of evidence 2A

Physical Therapy (pre-operative)

The primary purpose is to treat the patient’s TOS with out resorting to surgery.

Stage 1:

The goal of this initial stage is for the patient to decrease and obtain control of his/her symptoms resulting from TOS.

Early treatment will focus on symptom reduction before addressing biomechanical corrections. Cervical traction in combination with a hot pack and light exercise may reduce pain and irritable symptoms for some acute patients.[2]

Patient Education:

Avoidance: identify activities, postures, and actions that exacerbate symptoms in order to avoid them.[3]

Sleep positions: avoid arm abduction and overhead positions. Patients that wake up at night from pain are considered “releasers”. Some patients who can’t control positioning may need arm or leg sleeves to pin down. These patients should sleep on their uninvolved side or in supine with supportive pillows under the arms[2]

Prognosis: TOS process (with and with out treatment) and potential prognosis to encourage compliance with HEP and activity modifications[2]

Address the patient’s breathing techniques as the scalenes and other accessory muscles often compensate to elevate the ribcage during inspiration. Encouraging diaphragmatic breathing will lessen the work load on already overused or tight scalenes and can possibly reduce symptoms. Since exercise and vigorous aerobic activity promote heavy breathing, the patient should take caution to not exacerbate his/her symptoms.[2]

Stage 2:

Once the patient has control of his/her symptoms, the patient can move to this stage of treatment. The goal of this stage is to directly address the tissues that create structural limitations of motion and compression. Expect to exacerbate the patient’s symptoms a little, but it should not last past the treatment session.

Methods such as soft tissue manipulation and manual techniques can improve flexibility around the thoracic outlet. Joint mobilizations include the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, scapulothoracic, first rib, and cervical spine joints. A combination of these methods during treatment will increase the thoracic outlet space and relieve compression on the neurovascular structures. Nerve mobilization techniques such as sliding and tensioning will address the patient’s neural tension involvement.[3]

- Stretch: levator scapulae, the scalenes, pectoralis minor and major

- Strengthen for endurance: rhomboids, serratus anterior, lower & middle traps, other observed postural weaknesses

- Mobilizations [3][1][2]:

- 1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space

- Note: 1st rib mobility may irritate some patients

- Sternoclavicular jt

- Acromioclavicular jt

- Glenohumeral jt in anterior, posterior, inferior directions with arm elevation

- Cervical ROM

- 1st Rib mobility: to increase costocervical space

- Taping: some patients with severe symptoms respond to additional taping, adhesive bandages or braces that elevate and retract the shoulder girdle.[1]

- HEP[4]:

- Emphasize posture

- 1st rib self-mobilizations with a towel

- Additional endurance strengthening and stretches dosed by time

First Rib Mobilization: Patient seated. Thin sheet strap positioned around first rib. Pull strap towards opposite hip. Neck retracted, contralateral lateral flexion, and ipsilateral rotation. Ipsilateral head rotation emphasizes scalene stretch. Contralateral rotation emphasizes rib mobilization.

First Rib Mobilization: Patient seated. Thin sheet strap positioned around first rib. Pull strap towards opposite hip. Neck retracted, contralateral lateral flexion, and ipsilateral rotation. Ipsilateral head rotation emphasizes scalene stretch. Contralateral rotation emphasizes rib mobilization.

Posterior Glenohumeral Glide with Arm Flexion: Patient supine. Mobilizing hand contacts proximal humerus avoiding corocoid process. Force is directed posterolaterally (direction of thumb).

Posterior Glenohumeral Glide with Arm Flexion: Patient supine. Mobilizing hand contacts proximal humerus avoiding corocoid process. Force is directed posterolaterally (direction of thumb).

Post-Op Physical Therapy[3]

If a patient does require surgery, then physical therapy should follow immediately to prevent scar tissue and return the patient to full function.

Physical therapy typically lasts 3 months, with sessions 2-3x week.

Daily stretching for 2yrs to prevent scar contraction[3]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Journal Of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(2):74-83.

Hooper T, Denton J, McGalliard M, Brismée J, Sizer P. Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. June 2010;18(3):132-138.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

TOS can present in numerous ways due to the variety of tissues that can be involved (arteries, veins, nervous, and muscular tissue) and the different anatomical sites in which compression or entrapment can occur. In general, treatment for TOS should initially begin conservatively according to a literature review by Vanti et al, however, firm conclusions cannot be drawn from this review due to the lack of high quality evidence [1]. Conservative treatment seems to be effective at reducing symptoms, improving function, and facilitating return to work when compared to surgery.6 Higher quality studies are needed to compare conservative treatment to surgery, and even no treatment at all [1]. Physical therapy can assist patients given a TOS diagnosis utilizing an impairment-based approach, addressing muscle imbalances and postural changes that these patients commonly present with.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 1

This presentation was created by Walt Lingerfelt, Fellow in training at Evidence in Motion. Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 1 / View the presentation |

|

Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 2

This presentation was created by Walt Lingerfelt, Fellow in training at Evidence in Motion. Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 2 / View the presentation |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedVanti - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedhooper - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedgodges - ↑ Lindgren K. Thoracic outlet syndrome. International Musculoskeletal Medicine. March 2010;32(1):17-24. Accessed November 2, 2011.