General Overview of Osteoarthritis for Rehabilitation Professionals: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

* Bouchard's nodes | * Bouchard's nodes | ||

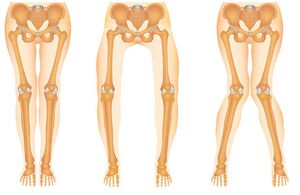

* genu varus/ valgus | * genu varus/ valgus | ||

<gallery widths="350px" heights="250px"> | |||

File:Anatomical Variations of the Knee - Genu Varum and Genu Valgum.jpg|Figure 1. From left to right: knee with normal alignment, genu varus and genu valgus. | |||

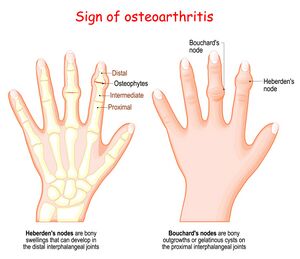

File:Heberden's and Bouchard's Nodes - Shutterstock - ID 1781524226.jpg|Figure 2. Heberden's and Bouchard's nodes. </gallery> | |||

== Osteoarthritis Management == | == Osteoarthritis Management == | ||

Revision as of 11:32, 13 May 2024

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic health condition. It can cause pain, decreased function, poor sleep, decreased mental health and reduced quality of life.[1][2] It is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and mortality.[3][4] General rehabilitation strategies for osteoarthritis include education, exercise and weight management. This page provides an overview of osteoarthritis, including epidemiology, risk factors and pathology, before considering diagnosis and management trends.

Definition[edit | edit source]

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) defines osteoarthritis as: “a disorder involving movable joints characterized by cell stress and extracellular matrix degradation initiated by micro- and macro-injury that activates maladaptive repair responses including pro-inflammatory pathways of innate immunity. The disease manifests first as a molecular derangement (abnormal joint tissue metabolism) followed by anatomic, and/or physiologic derangements (characterized by cartilage degradation, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, joint inflammation and loss of normal joint function), that can culminate in illness.”[5]

Key points:[6]

- osteoarthritis has traditionally been described as a degenerative cartilage disease, but our understanding has evolved and we know that there is a breakdown of the cartilage, as well as structural changes across the whole joint

- subchondral bone lesions precede cartilage degeneration

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that 240 million individuals have symptomatic osteoarthritis,[1] with a current prevalence rate of around 15%. This figure is expected to increase to 35% by 2030. This would make osteoarthritis the “single greatest cause of disability globally”.[7] Increased prevalence has been linked to our ageing populations and an increase in obesity and joint injuries.[7][8]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Known risk factors for osteoarthritis include ageing, obesity, acute trauma, chronic overload, gender and hormone profile, metabolic syndrome and genetic predisposition. However, osteoarthritis is not "the inevitable consequence of these factors [...and…] different risk factors may act together in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis".[7]

Ageing is characterised by progressive tissue loss and decreased organ function, and it "represents the single greatest risk factor for OA."[7]

Obesity is considered "the most prevalent preventable risk factor for developing osteoarthritis"[9]:

- previously obesity was considered a primary risk factor in knee osteoarthritis because of its impact on biomechanics, but it is now understood that it increases risk by altering metabolism and inflammation[9]

- obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in various joints, including the hand,[10] hip, knee, ankle and spine[9]

- obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in both males and females, but the effect size is greater in females[9]

Acute trauma / joint injury are considered "potent" risk factors for osteoarthritis.[1]

Chronic overload:

- various occupational ergonomic risk factors for osteoarthritis have been proposed, including force exertion, demanding postures, repetitive movements, hand-arm vibration, kneeling / squatting, lifting and climbing[11]

- these risk factors can increase the risk of developing knee or hip osteoarthritis compared to no exposure

- however, because the quality of evidence is currently low, there is "limited evidence of harmfulness"

- another systematic review found that physically demanding jobs (e.g. construction work, floor and bricklaying, fishing, farming, etc) are associated with increased risk of knee and hip osteoarthritis, and there may be a dose-response relationship[1]

Gender and hormone profile: there are gender differences in osteoarthritis across all joints (the cervical spine is one potential exception)[1]

Joint deformities: previous variation in the shape of bones / joints has been associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.[1]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis is a "dynamic and complex process, involving inflammatory, mechanical, and metabolic factors that result in the inability of the articular surface to serve its function of absorbing and distributing the mechanical load through the joint that ultimately leads to joint destruction."[7]

Its exact pathological mechanisms are still unknown, but changes within the joint are due to an interplay between various tissues in the osteochondral complex (e.g. adipose tissue, synovial tissue, ligaments, tendons, muscles).[7]

Osteoarthritis is typically characterised by:[7][12]

- degradation / destruction of the articular cartilage

- surface irregularities

- osteophyte formation

- subchondral bone remodelling / thickening

- synovial inflammation

- secondary inflammation of periarticular structures

It is a "heterogeneous disease that impacts all component tissues of the articular joint organ."[7]

Please watch the following optional video if you want to learn more about the pathology of osteoarthritis:

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

The pathological changes and symptoms caused by osteoarthritis vary considerably in each person.[7] But typical signs and symptoms associated with osteoarthritis include:[7][12][14]

- decreased range of motion

- stiffness

- pain

- deformity

- crepitus

- decreased mobility and functional limitations

- reduced / loss of ability to engage in “valued activities”, including walking, dancing, etc

These clinical changes / signs might only start to appear towards the end of disease progression.[7]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis can be confirmed radiographically on x-ray. Radiographic findings include:[7][12][14]

- joint space narrowing

- osteophytes

- subchondral sclerosis

- cyst formation

- abnormalities of bone contour

- ankylosis

Clinical vs Radiographic Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Knee Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Radiographic knee osteoarthritis requires structural changes on x-ray while clinical knee osteoarthritis is diagnosed based on a patient’s symptoms and the clinical examination.[15] However, radiography "is disputed because structural findings appear relatively late in the course of the disease and symptoms are not always associated with the structural findings."[15]

Key clinical signs of knee osteoarthritis:[8]

- knee pain and at least three of the following:

- aged over 50 years

- more than 30 minutes of morning stiffness

- crepitus

- bony tenderness

- bony enlargement

- no palpable warmth

Hip Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis has traditionally been diagnosed based on radiographic features, like the Kellgren and Lawrence score, but many guidelines recommend against using radiography as a diagnostic tool.[16] However, there is also no validated diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis, despite a general focus on early diagnosis[16]

Key clinical signs:[8]

- hip pain and:

- less than or equal to 15 degrees of hip internal rotation

- less than or equal to 115 degrees of hip flexion

Or

- hip pain and:

- aged more than 50 years

- less than or equal to 60 minutes of morning stiffness

- pain on internal rotation

- less than or equal to 15 degrees of hip internal rotation

Spine Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

There are no specific clinical criteria for identifying spine osteoarthritis (e.g. pain, morning stiffness, painful / reduced range of motion), but there is a known link between these criteria and lumbar disc degeneration.[17]

Joint Deformities[edit | edit source]

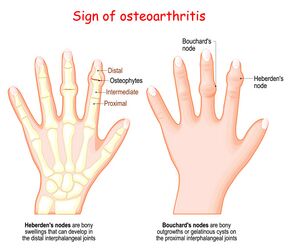

Specific joint deformities to look out for:[12]

- Heberden's nodes

- Bouchard's nodes

- genu varus/ valgus

- Anatomical Variations of the Knee - Genu Varum and Genu Valgum.jpg

Figure 1. From left to right: knee with normal alignment, genu varus and genu valgus.

Osteoarthritis Management[edit | edit source]

General management goals include:[12]

- maintaining / gaining range of motion

- increasing muscular support

- decreasing joint stress

- managing pain

Medical management may include:[12]

- medication, including anti-inflammatories, acetaminophen (paracetamol)

- encouraging weight loss

- surgical intervention (arthroscopy vs total joint replacements, etc)

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

"The clinical effect of PT [physical therapy] on pain and disability in hip or knee OA is substantial, while its associated costs are low."[8]

Key physiotherapy interventions for the hip and knee include patient education and exercise rehabilitation.[8]

Patient education topics include:[8]

- information about osteoarthritis and its potential consequences

- benefits of exercise / healthy lifestyle

- treatment options

- if arthroplasty (joint replacement) is planned, education should provide information about the surgery, rehabilitation timeframes, assistive devices, benefits of prehabilitation (i.e. maintaining strength and fitness pre-operatively), post-operative considerations, lifestyle restrictions and any precautions that may be necessary

Exercise rehabilitation should focus on joint-specific and general exercises that are individualised for each person's goals, requirements and preferences.

The following table summarises key Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type (FITT) principles for hip and knee osteoarthritis. It is adapted from Van Doormaal et al. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis.[8]

| FITT principle | Exercise recommendations |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Aim for at least 2 days per week of strengthening and 5 days of aerobic exercise |

| Intensity | Muscle strength training:

Aerobic training:

|

| Type | Aim for a combination of strength, aerobic and functional training

Strength exercises:

Aerobic exercise:

Functional training:

Can also include balance, coordination, neuromuscular and range of motion exercises if indicated |

| Time |

|

Key considerations for exercise rehabilitation:

- include a warm-up / cool down

- increase the intensity of training gradually (e.g. once per week) to the maximum level for the patient

- reduce the intensity of the next session if joint pain increases after a workout and persists for more than 2 hours after

- for patients who are untrained or limited by pain / mobility, start with short sessions (10 minutes or less)

- offer alternatives to exercises

- vary the number of sets, repetitions, intensity, duration of each session, type of exercise, rests, etc in consultation with the patient

Other interventions to consider:

- mobilisations

- assistive devices

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Feb;30(2):184-95.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Improving care for osteoarthritis: the forgotten chronic disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/docs/2022/oarsi_infographic_for_policymakers_2022_final.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Constantino de Campos G, Mundi R, Whittington C, Toutounji MJ, Ngai W, Sheehan B. Osteoarthritis, mobility-related comorbidities and mortality: an overview of meta-analyses. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Dec 25;12:1759720X20981219.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Is osteoarthritis a series disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/images/2020/oarsi-20-final-oa-infographic-_revised_copyright.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Standardization of osteoarthritis definitions. Available from: https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Coaccioli S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Zis P, Rinonapoli G, Varrassi G. Osteoarthritis: new insight on its pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 12;11(20):6013.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, Ocasio-Nieves BD, Yocum L, Lin H, Tuan RS. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: risk factors, regulatory pathways in chondrocytes, and experimental models. Biology (Basel). 2020 Jul 29;9(8):194.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Van Doormaal MCM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Peter WF. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020 Dec;18(4):575-95.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Batushansky A, Zhu S, Komaravolu RK, South S, Mehta-D'souza P, Griffin TM. Fundamentals of OA. An initiative of osteoarthritis and cartilage. Obesity and metabolic factors in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Apr;30(4):501-15.

- ↑ Plotz B, Bomfim F, Sohail MA, Samuels J. Current epidemiology and risk factors for the development of hand osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021 Jul 3;23(8):61.

- ↑ Hulshof CTJ, Pega F, Neupane S, Colosio C, Daams JG, Kc P, et al. The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2021 May;150:106349.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Cunningham S. Osteoarthritis Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ Osmosis from Elsevier. Osteoarthritis - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUOlmI-naFs [last accessed 13/05/2024]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Feb 9;325(6):568-78.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Törnblom M, Bremander A, Aili K, Andersson MLE, Nilsdotter A, Haglund E. Development of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and the associations to radiographic changes and baseline variables in individuals with knee pain: a 2-year longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 8;14(3):e081999.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Runhaar J, Özbulut Ö, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA; CREDO expert group. Diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis: first steps, based on the CHECK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5158-64.

- ↑ Van den Berg R, Chiarotto A, Enthoven WT, de Schepper E, Oei EHG, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Clinical and radiographic features of spinal osteoarthritis predict long-term persistence and severity of back pain in older adults. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022 Jan;65(1):101427.