Zellweger Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

The incidence of ZSDs is estimated to be 1 in 50.000 newborns in the United States.<ref>Steinberg SJ, Dodt G, Raymond GV, Braverman NE, Moser AB, Moser HW. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925443912000932 Peroxisome biogenesis disorders.] Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2006 Dec 1;1763(12):1733-48.</ref> It is presumed that ZSDs occur worldwide, but the incidence may differ between regions. For example, the incidence of (classic) Zellweger syndrome in the French-Canadian region of Quebec was estimated to be 1 in 12 [18]. A much lower incidence is reported in Japan, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 500.000 births [19]. More accurate incidence data about ZSDs will become available in the near future, since newborn screening for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy | The incidence of ZSDs is estimated to be 1 in 50.000 newborns in the United States.<ref>Steinberg SJ, Dodt G, Raymond GV, Braverman NE, Moser AB, Moser HW. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925443912000932 Peroxisome biogenesis disorders.] Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2006 Dec 1;1763(12):1733-48.</ref> It is presumed that ZSDs occur worldwide, but the incidence may differ between regions. For example, the incidence of (classic) Zellweger syndrome in the French-Canadian region of Quebec was estimated to be 1 in 12 [18]. A much lower incidence is reported in Japan, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 500.000 births [19]. More accurate incidence data about ZSDs will become available in the near future, since newborn screening for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy | ||

== | == Clinical Features == | ||

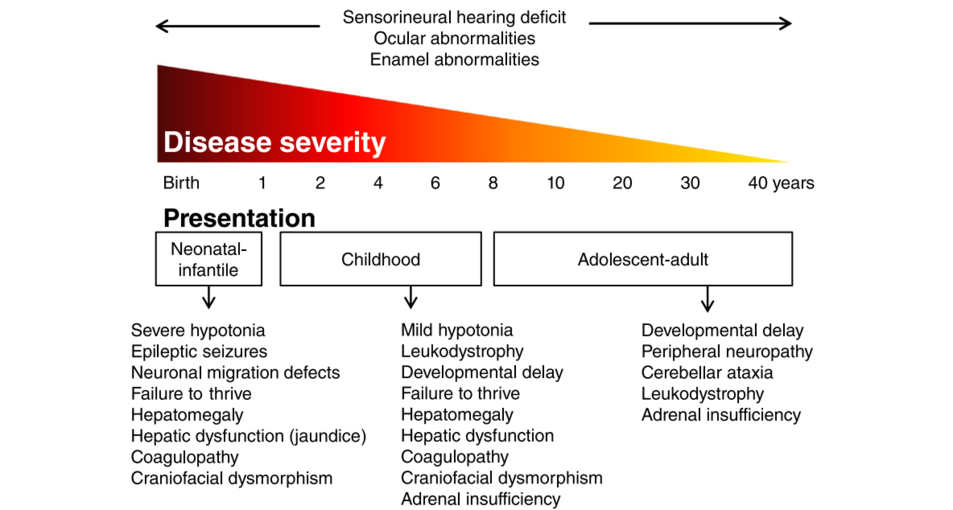

Patients with a ZSD can roughly be divided into three groups according to the age of presentation: the neonatal, infantile presentation, the childhood presentation and an adolescent-adult (late) presentation. | |||

===== Neonatal-Infantile Presentation ===== | |||

ZSD patients within this group typically present in the neonatal period with hepatic dysfunction and profound hypotonia resulting in prolonged jaundice and feeding difficulties. Epileptic seizures are usually present in these patients. Characteristic dysmorphic features can usually be found, of which the facial dysmorphic signs are most evident (Fig. 2a). Sensorineural deafness and ocular abnormalities like retinopathy, cataracts and glaucoma are typical but not always recognized at first presenta�tion. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show neocortical dysplasia (especially perisylvian polymicro�gyria), generalized decrease in white matter volume, delayed myelination, bilaterial ventricular dilatation and germinolytic cysts [23]. Neonatal onset leukodystrophy is rarely described [25]. Calcific stippling (chondrodys�plasia punctata) may be present, especially in the knees and hips. The neonatal-infantile presentation grossly resembles what was originally described as classic ZS. Prognosis is poor and survival is usually not beyond the first year of life. | |||

[[File:Screenshot 2023-11-26 074734.png|center|frameless|953x953px|Overview of zellweger spectrum disorders]] | |||

===== Childhood Presentation ===== | |||

These patients show a more varied symptomatology than ZSD patients with a neonatal-infantile presentation. Presentation usually involves delayed developmental milestone achievement. Ocular abnormalities comprise retinitis pigmentosa, cataract and glaucoma, often leading to early blindness and tun�nel vision. | |||

Sensorineural deafness is almost always present and usually discovered by auditory screening programs. Hepatomegaly and hepatic dysfunction with coagulopathy, elevated transaminases and (history of ) hyperbilirubinemia are common. Some patients develop epileptic seizures. Craniofacial dysmorphic features are generally less pronounced than in the neonatal-infantile group. | |||

Renal calcium oxalate stones and adrenal insufficiency may develop. Early-onset progres�sive leukodystrophy may occur, leading to loss of acquired skills and milestones in some individuals. The progressive demyelination is diffuse and affects the cerebrum, midbrain and cerebellum with involvement of the hilus of the dentate nucleus and the peridentate white matter. | |||

Sequential imaging in three ZSD patients showed that the earliest abnormalities related to demyelination were consistently seen in the hilus of the dentate nucleus and superior cerebellar peduncles, chronologically followed by the cerebellar white matter, brainstem tracts, parieto-occipital white matter, splenium of the corpus callosum and eventually involvement of the whole of the cerebral white matter. | |||

A small subgroup of patients develop a relatively late-onset white matter disease, but no patients with late-onset rapid progressive white matter disease after the age of five have been reported. Prognosis depends on what organ systems are primarily affected (i.e. liver) and the occurrence of progressive cerebral demyelination, but life expectancy is decreased and most patients die before adolescence. | |||

===== Adolescent-Adult Presentation ===== | |||

Symptoms in this group are less severe, and diagnosis can be in late child- or even adulthood. Ocular abnormalities and a sensorineural hearing deficit are the most consistent symptoms. Craniofacial dysmorphic features can be present, but may also be completely absent. | |||

Developmental delay is highly variable and some patients may have normal intelligence. Daily functioning ranges from completely independent to 24 h care. It is important to emphasize that primary adrenal insufficiency is common and is probably under diagnosed. In addition to some degree of developmental delay, other neurological abnormalities are usually also present: | |||

* signs of peripheral neuropathy, | |||

* cerebellar ataxia and | |||

* pyramidal tract signs. | |||

The clinical course is usually slowly progressive, although the disease may remain stable for many years. Slowly progressive, clinically silent leukoencephalopathy is common, but MRI may be normal in other cases. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 09:10, 26 November 2023

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Ayodeji Mark-Adewunmi

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Zellweger syndrome is a rare congenital disorder characterized by the reduction or absence of functional peroxisomes in the cells of an individual.[1] It is one of a family of disorders called Zellweger spectrum disorders which are leukodystrophies. Zellweger syndrome is named after Hans Zellweger (1909–1990), a Swiss-American pediatrician, a professor of pediatrics and genetics at the University of Iowa who researched this disorder.

Zellweger spectrum disorder, also known as cerebrohepatorenal syndrome, is a rare inherited disorder characterized by the absence/reduction of functional peroxisomes in cells, which are essential for beta-oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids. It is autosomal recessive in inheritance, and the spectrum of the disease includes Zellweger syndrome (ZS), neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy (NALD), infantile Refsum disease (IRD), and rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata type 1 (RCDP1) depending on the phenotype and severity.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Zellweger syndrome is the result of a mutation in any of the 12 PEX genes. Most cases of Zellweger syndrome are due to a mutation in the PEX1 gene. These genes control peroxisomes, which are needed for normal cell function.

ZSDs are caused by mutations in one of the 13 different PEX genes. PEX genes encode proteins called peroxins and are involved in either peroxisome formation, peroxisomal protein import, or both. As a consequence, mutations in PEX genes cause a deficiency of functional peroxisomes.[3] Cells from ZSD patients either entirely lack functional peroxisomes, or cells can show a reduced number of functional peroxisomes or a mosaic pattern (i.e. a mixed population of cells with functional peroxisomes and cells without). Peroxisomes are involved in many anabolic and catabolic metabolic processes, like biosynthesis of ether phospholipids and bile acids, α- and β-oxidation of fatty acids and the detoxification of glyoxylate and reactive oxygen species. Dysfunctional peroxisomes therefore cause biochemical abnormalities in tissues, but also in readily available materials like plasma and urine.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of ZSDs is estimated to be 1 in 50.000 newborns in the United States.[4] It is presumed that ZSDs occur worldwide, but the incidence may differ between regions. For example, the incidence of (classic) Zellweger syndrome in the French-Canadian region of Quebec was estimated to be 1 in 12 [18]. A much lower incidence is reported in Japan, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 500.000 births [19]. More accurate incidence data about ZSDs will become available in the near future, since newborn screening for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

Patients with a ZSD can roughly be divided into three groups according to the age of presentation: the neonatal, infantile presentation, the childhood presentation and an adolescent-adult (late) presentation.

Neonatal-Infantile Presentation[edit | edit source]

ZSD patients within this group typically present in the neonatal period with hepatic dysfunction and profound hypotonia resulting in prolonged jaundice and feeding difficulties. Epileptic seizures are usually present in these patients. Characteristic dysmorphic features can usually be found, of which the facial dysmorphic signs are most evident (Fig. 2a). Sensorineural deafness and ocular abnormalities like retinopathy, cataracts and glaucoma are typical but not always recognized at first presenta�tion. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show neocortical dysplasia (especially perisylvian polymicro�gyria), generalized decrease in white matter volume, delayed myelination, bilaterial ventricular dilatation and germinolytic cysts [23]. Neonatal onset leukodystrophy is rarely described [25]. Calcific stippling (chondrodys�plasia punctata) may be present, especially in the knees and hips. The neonatal-infantile presentation grossly resembles what was originally described as classic ZS. Prognosis is poor and survival is usually not beyond the first year of life.

Childhood Presentation[edit | edit source]

These patients show a more varied symptomatology than ZSD patients with a neonatal-infantile presentation. Presentation usually involves delayed developmental milestone achievement. Ocular abnormalities comprise retinitis pigmentosa, cataract and glaucoma, often leading to early blindness and tun�nel vision.

Sensorineural deafness is almost always present and usually discovered by auditory screening programs. Hepatomegaly and hepatic dysfunction with coagulopathy, elevated transaminases and (history of ) hyperbilirubinemia are common. Some patients develop epileptic seizures. Craniofacial dysmorphic features are generally less pronounced than in the neonatal-infantile group.

Renal calcium oxalate stones and adrenal insufficiency may develop. Early-onset progres�sive leukodystrophy may occur, leading to loss of acquired skills and milestones in some individuals. The progressive demyelination is diffuse and affects the cerebrum, midbrain and cerebellum with involvement of the hilus of the dentate nucleus and the peridentate white matter.

Sequential imaging in three ZSD patients showed that the earliest abnormalities related to demyelination were consistently seen in the hilus of the dentate nucleus and superior cerebellar peduncles, chronologically followed by the cerebellar white matter, brainstem tracts, parieto-occipital white matter, splenium of the corpus callosum and eventually involvement of the whole of the cerebral white matter.

A small subgroup of patients develop a relatively late-onset white matter disease, but no patients with late-onset rapid progressive white matter disease after the age of five have been reported. Prognosis depends on what organ systems are primarily affected (i.e. liver) and the occurrence of progressive cerebral demyelination, but life expectancy is decreased and most patients die before adolescence.

Adolescent-Adult Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms in this group are less severe, and diagnosis can be in late child- or even adulthood. Ocular abnormalities and a sensorineural hearing deficit are the most consistent symptoms. Craniofacial dysmorphic features can be present, but may also be completely absent.

Developmental delay is highly variable and some patients may have normal intelligence. Daily functioning ranges from completely independent to 24 h care. It is important to emphasize that primary adrenal insufficiency is common and is probably under diagnosed. In addition to some degree of developmental delay, other neurological abnormalities are usually also present:

- signs of peripheral neuropathy,

- cerebellar ataxia and

- pyramidal tract signs.

The clinical course is usually slowly progressive, although the disease may remain stable for many years. Slowly progressive, clinically silent leukoencephalopathy is common, but MRI may be normal in other cases.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Brul S, Westerveld A, Strijland A, Wanders RJ, Schram AW, Heymans HS, Schutgens RB, Van Den Bosch H, Tager JM. Genetic heterogeneity in the cerebrohepatorenal (Zellweger) syndrome and other inherited disorders with a generalized impairment of peroxisomal functions. A study using complementation analysis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1988 Jun 1;81(6):1710-5.

- ↑ Powers JM, Tummons RC, Caviness Jr VS, Moser AB, Moser HW. Structural and chemical alterations in the cerebral maldevelopment of fetal cerebro-hepato-renal (Zellweger) syndrome. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 1989 May 1;48(3):270-89.

- ↑ Waterham HR, Ebberink MS. Genetics and molecular basis of human peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2012 Sep 1;1822(9):1430-41.

- ↑ Steinberg SJ, Dodt G, Raymond GV, Braverman NE, Moser AB, Moser HW. Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2006 Dec 1;1763(12):1733-48.