Pre Pointe Assessment: Difference between revisions

Carin Hunter (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Carin Hunter|Carin Hunter]] based on the course by [https://members.physio-pedia.com/course_tutor/michelle-green-smerdon// Michelle Green-Smerdon]<br> '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Dance injuries associated with pointe work are highly prevalent within the dance community,<ref name=":0">Altmann C, Roberts J, Scharfbillig R, Jones S. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2019/00000023/00000001/art00006 Readiness for en pointe work in young ballet dancers are there proven screening tools and training protocols for a population at increased risk of injury?]. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2019 Mar 15;23(1):40-5.</ref> particularly in young dancers who are growing and, at the same time, having to learn motor patterns and technically demanding skills.<ref name=":1">Richardson M, Liederbach M, Sandow E. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2010/00000014/00000003/art00002 Functional criteria for assessing pointe-readiness.] Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2010 Sep 1;14(3):82-8.</ref> Pre-pointe assessments are used to determine whether a ballet dancer is safe to progress to dancing en pointe. This transition often occurs at around 12 years of age.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2">DeWolf A, McPherson A, Besong K, Hiller C, Docherty C. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2018/00000022/00000004/art00005 Quantitative measures utilized in determining pointe readiness in young ballet dancers.] Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2018 Dec 1;22(4):209-17.</ref> | |||

Basic evaluation protocols have not yet been standardised <ref>Cantergi D, Moraes LR, Loss JF. Applications of Biomechanics Analysis in Dance. InScientific Perspectives and Emerging Developments in Dance and the Performing Arts 2021 (pp. 25-44). IGI Global.</ref>, but attempts have been made to identify musculoskeletal variables between pre-pointe and novice pointe students to ascertain readiness.<ref name=":2" /> Previously, chronological age, years of dance training, ankle plantar flexion range, and correct execution of relevé were the only indicators of readiness. However, research suggests that a combination of a biomechanical assessment, and an assessment of the entire kinetic chain, muscle imbalance, compensation, and other postural issues is more useful to gauge safe and successful performance.<ref name=":1" /> Similarly, there is a lack of research regarding pre-pointe training programmes. While a programme is often introduced and is very beneficial, there is no gold standardised programme.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

There is much debate over who should complete the pre-pointe assessment for the dancer, but it is thought that a healthcare provider has the greatest influence over the pre-pointe assessment.<ref>Russell JA. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3871955/ Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives.] Open access journal of sports medicine. 2013;4:199.</ref> It has also been suggested that functional tests which examine core stability, strength and flexibility of the feet and ankles, lower extremity alignment and postural control may be adequate to determine when a dancer is ready to begin pointe work.<ref>Glumm SA. [https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/13992sbg5276 Functional Performance Criteria to Assess Pointe Readiness in Youth Ballet Dancers.]</ref> | |||

Please see the glossary at the bottom of this page for definitions of any unfamiliar ballet terms. | |||

=== General Criteria Used === | |||

# '''Age''' | |||

#* Dancers are often encouraged to start pointe work between 11 and 12 years of age. There is a large variation in musculoskeletal and motor development at this age. There are regular, rapid growth spurts which can heighten the risk of growth plate injuries<ref name=":7">Green-Smerdon M. Pre-Pointe Assessment Course. Plus. 2022.</ref> | |||

# '''Years of dance''' | |||

#* It is assumed that by 12 years of age, a dancer will have participated in at least 3 or 4 years of classical ballet training, and therefore, will have the necessary cognitive ability, strength, technique skill, alignment, coordination, bone development and motor control to begin pointe work<ref>McCormack MC, Bird H, de Medici A, Haddad F, Simmonds J. [https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/a-0798-3570 The physical attributes most required in professional ballet: a Delphi study.] Sports medicine international open. 2019 Jan;3(01):E1-5.</ref> | |||

# '''Injuries''' | |||

#* Dance students will compensate for newly acquired injuries, or injuries that have not fully healed | |||

# '''Relevé alignment and stability''' | |||

# '''Plié alignment and stability''' | |||

# '''Tendu''' | |||

#'''Upper body alignment and stability''' | |||

#'''Technique requirements and skill acquisition''' | |||

#*When assessing a dancer, commonly technique in carrying out certain movements is assessed. According to Meck,<ref>Meck C, Hess RA, Helldobler R, Roh J. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2004/00000008/00000002/art00001 Pre-pointe evaluation components used by dance schools]. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2004 Jun 1;8(2):37-42.</ref> the most valuable input with regards to requirements of technique were to focus of assessing a relevé, plié, and tendu. | |||

#*The requirement of sufficient ankle plantar flexion range of motion is essential for pointe work | |||

== Strength Testing == | |||

==== Intrinsic Muscle Strength ==== | |||

When a dancer moves to full pointe, the intrinsic muscles of the foot work 2.5 to 3 times harder than the other muscles in the foot.<ref>Barreau X, Gil C, Thoreux P. [https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-60752-7_110 Ballet. Injury and Health Risk Management in Sports] 2020 (pp. 725-731). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.</ref> Because of the repetitive nature of ballet, chronic fatigue of the muscles which cross the joints of the foot are a major factor in injuries associated with pointe work.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

==== Lower Extremity Strength and Neuromuscular Control ==== | |||

When assessing lower extremity strength, it is important to look at the kinetic chain as a whole. This is because the kinetics of the lower limb are largely dependent on pelvis and trunk stability. To gain stability of the pelvis and trunk, a dancer needs to activate their core muscles. This helps provide them with the control needed to execute the necessary movements.<ref>Willson JD, Dougherty CP, Ireland ML, Davis IM. [https://journals.lww.com/jaaos/Abstract/2005/09000/Core_Stability_and_Its_Relationship_to_Lower.5.aspx Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury.] JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005 Sep 1;13(5):316-25.</ref> | |||

In single-leg stance, a dancer relies heavily on their hip abductor and external rotator muscles to maintain a level pelvis. This becomes increasingly challenging when the base of support is further decreased (i.e. when rising up onto pointe). Compensations can be seen further up the kinetic chain in the form of increased postural sway. This can also increase a dancer's risk of inversion sprains.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

== Evidence-Based Tests == | |||

While there is no gold standard, certain evidence-based tests may give an idea of pointe readiness and are recommended in a pre-pointe assessment.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

The '''single leg heel rise test''' can provide an objective measure of plantar flexion strength and it can be used to help determine a dancer’s readiness for pointe training. Performing 25 single leg heel rises is considered normal for human gait.<ref>Hébert-Losier K, Wessman C, Alricsson M, Svantesson U. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031940617300226 Updated reliability and normative values for the standing heel-rise test in healthy adults.] Physiotherapy. 2017 Dec 1;103(4):446-52.</ref> <ref>Thomas KS. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2003/00000007/00000004/art00002 Functional eleve performance as it applies to heel-rises in performance-level collegiate dancers.] Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2003 Dec 15;7(4):115-20.</ref> | |||

DeWolf et al.<ref name=":2" /> also advise that 15 continuous '''single-leg relevés''' and 2 cycles of the '''airplane test''' should be considered "cut-off levels" when performing pre-pointe assessments. | |||

Evaluating dynamic motor control, such as controlling alignment during ballet specific tasks, can also be useful in the pre-pointe assessment.<ref name=":3" /> The '''airplane test''', '''topple test''' and '''sauté test''' were able to distinguish between dancers of varying levels (i.e. pre-pointe, beginner pointe and intermediate pointe) and may be useful for determining pointe readiness.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | |||

and | The '''relevé endurance test''' and the '''airplane tes'''t can both be used to distinguish between pre-pointe and pointe dancers.<ref name=":2" /> These tests also discriminated between dancers of different skill levels, integrating both technique and physical ability.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

==== 1. “Airplane” Test <ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3">Richardson M, Liederbach M, Sandow E. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2010/00000014/00000003/art00002 Functional criteria for assessing pointe-readiness.] Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2010 Sep 1;14(3):82-8.</ref><ref name=":4">Hewitt S, Mangum M, Tyo B, Nicks C. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2016/00000020/00000004/art00003 Fitness testing to determine pointe readiness in ballet dancers.] Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2016 Dec 15;20(4):162-7.</ref><ref name=":6">Batalden L. [https://www.proquest.com/openview/d70eb2979a20a874508323e2a67e1fed/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=5425112 Pointe-Readiness Screening and Exercise for the Young Studio Dancer.] Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2020;32(1):48-50.</ref> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To measure control of the lower extremities, core and balance. Hewitt et al.<ref name=":4" /> have found that this test is a useful way of determining a dancer's ability to hold their pelvis in a neutral position. | |||

. | '''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer stands with feet parallel on one leg. They bend over at the waist and extend the non-support leg backwards, until the leg and the trunk are parallel to the floor. In this position, the dancer is facing down towards the floor. Here, they lift their arms beside their torso in the shape of a “T.” Once the torso and leg are parallel with the floor, the dancer bends their supporting leg. At the same time, while keeping the trunk and non-support leg parallel to the floor, they bring their arms down towards the floor (elbows extended) until the fingertips make contact with the floor in front of their face. The dancer then extends their knee and arms to return to the starting position. The test is stopped if the dancer moves their supporting foot, falls out of the position, or chooses to stop. The number of completed repetitions on both sides are added together for a total score.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' Test both right and left sides. | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' An attempt is considered unsuccessful when there is pelvic drop, hip adduction, hip internal rotation, knee valgus, or foot pronation during the movement.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|huzr00t9aAU}} | |||

==== 2. Sauté Test <ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To evaluate dynamic trunk control and the alignment of the lower limb.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer begins in coupé derriere. Their gesturing leg and standing leg are turned out and they place their hands on their hips or across their chest. The dancer jumps into the air and must achieve the following:<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* | * Neutral pelvis | ||

* The | * Upright / stable trunk | ||

* | * Straight standing leg in the air | ||

* Pointed standing foot in the air | |||

* The leg holding the coupé must not move | |||

* Their landing into plié must be controlled (i.e. they roll through the foot from toe to ball to heel) | |||

Participants in the study by Hewitt et al.<ref name=":4" /> attempted as many as 16 sautés on each leg. They added scores from the right and left sides together to find the total score. A pass was a minimum of 8/16 correctly performed jumps.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' The single leg sauté test should not follow the single leg heel raise test as both tests primarily evaluate calf muscle strength.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' Slow motion analysis is necessary to assess all the criteria required to pass the test.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":4" /> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|Q6NmwsfqbEM}} | |||

==== 3. “Topple” Test<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To assess a dancer’s ability to perform one clean pirouette.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' A "clean" pirouette is defined as:<ref name=":4" /> | |||

#A proper beginning placement (i.e. square hips, the majority of weight is on the forefoot, a turned out position, the pelvis is centred, and the dancer has strong arms) | |||

#The dancer brings their leg up into passé in one count | |||

#The supporting leg is straightened | |||

#The dancer turns their torso in "one piece" | |||

#The dancer's arms are "strong" and must be properly placed | |||

#The dancer demonstrates a quick spot | |||

#The landing must be controlled | |||

In the Hewitt et al.<ref name=":4" /> study, one point was given for each criterion that was met. The best pirouette on each leg was given a score and a total score was given based on the scores from the right and left legs.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' Dancers in the study by Hewitt et al.<ref name=":4" /> were given three attempts to complete the pirouette on each leg. | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' The tests should be recorded, so that videos can be replayed in slow motion for a more precise analysis.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|GDoFnUXd86c}} | |||

==== 4. Pencil Test – Plantar Flexion ROM<ref name=":3" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To determine the overall plantar flexion of the ankle-foot complex.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer is positioned in long-sitting. A straight-edge level or a pencil is placed on the top of their dorsal talar neck. A dancer passes this test if they achieve sufficient plantar flexion (i.e. 90 degrees or more). This is achieved when the straight-edge clears the distal end of the tibia, just proximal to the malleoli.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' A hypermobile individual will perform well in this test.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' It is important to correct excessive rounding of the foot.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

==== 5. Single Leg Heel Raise Test <ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To determine the endurance of the calf musculature.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer stands on one leg. They hold their other leg in a parallel coupé. The dancer is asked to perform as many relevés without plié as they can to a beat of 120 beats per minute (i.e. 30 heel raises per minute). The test is ended if the dancer can no longer keep up with the beat or if they choose to stop. The test is also stopped if a dancer completes 75 relevés. Each side is tested and the total number of relevés are added together.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

This test can also be performed as follows: Posterior calf strength is measured by counting the number of parallel single-leg heel raises that the dancer can perform while maintaining the pre-test relevé height on a straight leg. A “pass” for this test has been defined as performing 20 or more heel raises.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' Batalden<ref name=":6" /> notes that at least 90 degrees of plantar flexion is needed for the subtalar joint to lock en pointe, thus helping to avoid ankle ligament injuries. In their testing, Batalden<ref name=":6" /> included dorsiflexion "with a standard of 15°". | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' For 5 to 8 year olds, the mean number of repetitions in the heel raise test has been found to be 15.2 repetitions. The mean number of repetitions in 9 to 12 year olds is 27.7.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|CSHfBTXf484}} | |||

==== 6. Double Leg Lower Test<ref name=":3" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To objectively evaluate abdominal strength.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer lies supine. Their pelvis is in a neutral position and both legs are flexed to 90 degrees at the hips, so that they are perpendicular to the testing surface. While keeping both knees extended, the dancer is asked to slower lower their legs to the testing surface. The assessor looks at pelvis stability and records the angle of the legs when the pelvis begins to tilt anteriorly. A strength grade is given based on this angle.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' This test is recorded as a pass if this angle is 45 degrees or less.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' Watch for any biomechanical compensations further up the body.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

==== 7. Modified “Romberg” Test<ref name=":3" /><ref>Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Hoffman HJ, Sklare DA, Schubert MC. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3190311/ The modified Romberg Balance Test: normative data in US adults.] Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2011 Oct;32(8):1309.</ref><ref name=":5">Ani KU, Ibikunle PO, Nwosu CC, Ani NC. [https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jmrp/jdms/2021/00000025/00000004/art00001 Are the Current Balance Screening Tests in Dance Medicine Specific Enough for Tracking the Effectiveness of Balance-Related Injury Rehabilitation in Dancers?] A Scoping Review. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2021 Dec 15;25(4):217-30.</ref>==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To determine proprioception and falls risk.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer stands in a single-leg parallel stance. They cross their arms and close their eyes. A dancer passes this test if they can maintain this position for more than 30 seconds without: opening their eyes, touching the non-support foot down, or moving their stance foot.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

Please click on the link for more information on the [[Romberg Test]]. | |||

==== 8. Timed Plank Test<ref name=":4" /> ==== | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To assess core endurance and the ability to maintain a neutral pelvis position.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' The dancer starts in a full plank position on their hands and toes. They must achieve proper pelvic alignment before the test can start. The assessor times how long the dancer can hold this position. The test ends when the dancer can no longer hold the pelvis in the correct position or drops to their knees. It is also stopped after five minutes.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

'''<u>Note</u>:''' Being able to keep the core still while maintaining a neutral pelvis is important for control and balance during barre and centre work.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

==== 9. Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT)<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":5" />==== | |||

[[File:SEBT.png|right|frameless]] | |||

'''<u>Aim</u>:''' To measure dynamic balance.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

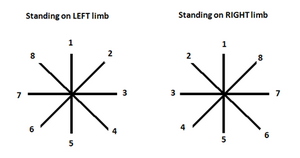

'''<u>Instruction</u>:''' There are two versions of this test commonly used, both have links to pages describing the tests further. This course refers to a test known as the "[[Y Balance Test]]", in which the individual, balances on one leg and touches 3 different points on the floor with the non-weightbearing foot. The second test is referred to as the [[Star Excursion Balance Test|Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT)]], as pictured along side. in this test four strips of athletic tape are cut (each strip is 6-8 feet long). Two pieces are used to create a '+' while the other two strips are used to create an 'x', which is positioned on top of the '+', thus forming a star shape. Each strip must be separated by a 45 degree angle.<ref name=":8">Olmsted LC, Carcia CR, Hertel J, Shultz SJ. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC164384/ Efficacy of the star excursion balance tests in detecting reach deficits in subjects with chronic ankle instability.] Journal of athletic training. 2002 Oct;37(4):501.</ref> During the SEBT, the aim is to maintain single-leg stance while reaching the contralateral leg as far as possible along the points of the star.<ref name=":8" /><ref>Plisky PJ, Gorman PP, Butler RJ, Kiesel KB, Underwood FB, Elkins B. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2953327/ The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test.] North American journal of sports physical therapy: NAJSPT. 2009 May;4(2):92.</ref> | |||

'''<u>Remember</u>:''' Complete the test in all required directions. | |||

==== Guidelines from the International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS)<ref name=":9">Weiss DS, Rist RA, Grossman G. [https://iadms.org/media/5779/iadms-resource-paper-guidelines-for-initiating-pointe-training.pdf Guidelines for Initiating Pointe Training.] Journal of Dance Medicine ci Science• Volunae. 2009;13(3):91.</ref>==== | |||

The IADMS provides the following guidelines for when to begin pointe training:<ref name=":9" /> | |||

#"Not before age 12. | |||

#If the student is not anatomically sound (e.g., insufficient ankle and foot plantar flexion range of motion; poor lower extremity alignment), do not allow pointe work. | |||

#If she is not truly pre-professional, discourage pointe training. | |||

#If she has weak trunk and pelvic (“core”) muscles or weak legs, delay pointe work (and consider implementing a strengthening program). | |||

#If the student is hypermobile in the feet and ankles, delay pointe work (and consider implementing a strengthening program). | |||

#If ballet classes are only once a week, discourage pointe training. | |||

#If ballet classes are twice a week, and none of the above applies, begin in the fourth year of training." | |||

== Ballet Terms Explained == | |||

{{pdf|PAglossary.pdf|Glossary of Ballet Terms}} | |||

== References == | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | [[Category:Course Pages]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Foot - Assessment and Examination]] | ||

[[Category:Ankle - Assessment and Examination]] | |||

[[Category:Ankle]] | |||

[[Category:Foot]] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:05, 22 January 2023

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dance injuries associated with pointe work are highly prevalent within the dance community,[1] particularly in young dancers who are growing and, at the same time, having to learn motor patterns and technically demanding skills.[2] Pre-pointe assessments are used to determine whether a ballet dancer is safe to progress to dancing en pointe. This transition often occurs at around 12 years of age.[1][2][3]

Basic evaluation protocols have not yet been standardised [4], but attempts have been made to identify musculoskeletal variables between pre-pointe and novice pointe students to ascertain readiness.[3] Previously, chronological age, years of dance training, ankle plantar flexion range, and correct execution of relevé were the only indicators of readiness. However, research suggests that a combination of a biomechanical assessment, and an assessment of the entire kinetic chain, muscle imbalance, compensation, and other postural issues is more useful to gauge safe and successful performance.[2] Similarly, there is a lack of research regarding pre-pointe training programmes. While a programme is often introduced and is very beneficial, there is no gold standardised programme.[5]

There is much debate over who should complete the pre-pointe assessment for the dancer, but it is thought that a healthcare provider has the greatest influence over the pre-pointe assessment.[6] It has also been suggested that functional tests which examine core stability, strength and flexibility of the feet and ankles, lower extremity alignment and postural control may be adequate to determine when a dancer is ready to begin pointe work.[7]

Please see the glossary at the bottom of this page for definitions of any unfamiliar ballet terms.

General Criteria Used[edit | edit source]

- Age

- Dancers are often encouraged to start pointe work between 11 and 12 years of age. There is a large variation in musculoskeletal and motor development at this age. There are regular, rapid growth spurts which can heighten the risk of growth plate injuries[5]

- Years of dance

- It is assumed that by 12 years of age, a dancer will have participated in at least 3 or 4 years of classical ballet training, and therefore, will have the necessary cognitive ability, strength, technique skill, alignment, coordination, bone development and motor control to begin pointe work[8]

- Injuries

- Dance students will compensate for newly acquired injuries, or injuries that have not fully healed

- Relevé alignment and stability

- Plié alignment and stability

- Tendu

- Upper body alignment and stability

- Technique requirements and skill acquisition

- When assessing a dancer, commonly technique in carrying out certain movements is assessed. According to Meck,[9] the most valuable input with regards to requirements of technique were to focus of assessing a relevé, plié, and tendu.

- The requirement of sufficient ankle plantar flexion range of motion is essential for pointe work

Strength Testing[edit | edit source]

Intrinsic Muscle Strength[edit | edit source]

When a dancer moves to full pointe, the intrinsic muscles of the foot work 2.5 to 3 times harder than the other muscles in the foot.[10] Because of the repetitive nature of ballet, chronic fatigue of the muscles which cross the joints of the foot are a major factor in injuries associated with pointe work.[5]

Lower Extremity Strength and Neuromuscular Control[edit | edit source]

When assessing lower extremity strength, it is important to look at the kinetic chain as a whole. This is because the kinetics of the lower limb are largely dependent on pelvis and trunk stability. To gain stability of the pelvis and trunk, a dancer needs to activate their core muscles. This helps provide them with the control needed to execute the necessary movements.[11]

In single-leg stance, a dancer relies heavily on their hip abductor and external rotator muscles to maintain a level pelvis. This becomes increasingly challenging when the base of support is further decreased (i.e. when rising up onto pointe). Compensations can be seen further up the kinetic chain in the form of increased postural sway. This can also increase a dancer's risk of inversion sprains.[5]

Evidence-Based Tests[edit | edit source]

While there is no gold standard, certain evidence-based tests may give an idea of pointe readiness and are recommended in a pre-pointe assessment.[5]

The single leg heel rise test can provide an objective measure of plantar flexion strength and it can be used to help determine a dancer’s readiness for pointe training. Performing 25 single leg heel rises is considered normal for human gait.[12] [13]

DeWolf et al.[3] also advise that 15 continuous single-leg relevés and 2 cycles of the airplane test should be considered "cut-off levels" when performing pre-pointe assessments.

Evaluating dynamic motor control, such as controlling alignment during ballet specific tasks, can also be useful in the pre-pointe assessment.[14] The airplane test, topple test and sauté test were able to distinguish between dancers of varying levels (i.e. pre-pointe, beginner pointe and intermediate pointe) and may be useful for determining pointe readiness.[3][14][15]

The relevé endurance test and the airplane test can both be used to distinguish between pre-pointe and pointe dancers.[3] These tests also discriminated between dancers of different skill levels, integrating both technique and physical ability.[3][14][15]

1. “Airplane” Test [3][14][15][16][edit | edit source]

Aim: To measure control of the lower extremities, core and balance. Hewitt et al.[15] have found that this test is a useful way of determining a dancer's ability to hold their pelvis in a neutral position.

Instruction: The dancer stands with feet parallel on one leg. They bend over at the waist and extend the non-support leg backwards, until the leg and the trunk are parallel to the floor. In this position, the dancer is facing down towards the floor. Here, they lift their arms beside their torso in the shape of a “T.” Once the torso and leg are parallel with the floor, the dancer bends their supporting leg. At the same time, while keeping the trunk and non-support leg parallel to the floor, they bring their arms down towards the floor (elbows extended) until the fingertips make contact with the floor in front of their face. The dancer then extends their knee and arms to return to the starting position. The test is stopped if the dancer moves their supporting foot, falls out of the position, or chooses to stop. The number of completed repetitions on both sides are added together for a total score.[15]

Remember: Test both right and left sides.

Note: An attempt is considered unsuccessful when there is pelvic drop, hip adduction, hip internal rotation, knee valgus, or foot pronation during the movement.[15]

2. Sauté Test [14][15][16][edit | edit source]

Aim: To evaluate dynamic trunk control and the alignment of the lower limb.[15]

Instruction: The dancer begins in coupé derriere. Their gesturing leg and standing leg are turned out and they place their hands on their hips or across their chest. The dancer jumps into the air and must achieve the following:[15]

- Neutral pelvis

- Upright / stable trunk

- Straight standing leg in the air

- Pointed standing foot in the air

- The leg holding the coupé must not move

- Their landing into plié must be controlled (i.e. they roll through the foot from toe to ball to heel)

Participants in the study by Hewitt et al.[15] attempted as many as 16 sautés on each leg. They added scores from the right and left sides together to find the total score. A pass was a minimum of 8/16 correctly performed jumps.[15]

Remember: The single leg sauté test should not follow the single leg heel raise test as both tests primarily evaluate calf muscle strength.[5]

Note: Slow motion analysis is necessary to assess all the criteria required to pass the test.[5][15]

3. “Topple” Test[14][15][16][edit | edit source]

Aim: To assess a dancer’s ability to perform one clean pirouette.[15]

Instruction: A "clean" pirouette is defined as:[15]

- A proper beginning placement (i.e. square hips, the majority of weight is on the forefoot, a turned out position, the pelvis is centred, and the dancer has strong arms)

- The dancer brings their leg up into passé in one count

- The supporting leg is straightened

- The dancer turns their torso in "one piece"

- The dancer's arms are "strong" and must be properly placed

- The dancer demonstrates a quick spot

- The landing must be controlled

In the Hewitt et al.[15] study, one point was given for each criterion that was met. The best pirouette on each leg was given a score and a total score was given based on the scores from the right and left legs.[15]

Remember: Dancers in the study by Hewitt et al.[15] were given three attempts to complete the pirouette on each leg.

Note: The tests should be recorded, so that videos can be replayed in slow motion for a more precise analysis.[15]

4. Pencil Test – Plantar Flexion ROM[14][edit | edit source]

Aim: To determine the overall plantar flexion of the ankle-foot complex.[14]

Instruction: The dancer is positioned in long-sitting. A straight-edge level or a pencil is placed on the top of their dorsal talar neck. A dancer passes this test if they achieve sufficient plantar flexion (i.e. 90 degrees or more). This is achieved when the straight-edge clears the distal end of the tibia, just proximal to the malleoli.[14]

Remember: A hypermobile individual will perform well in this test.[5]

Note: It is important to correct excessive rounding of the foot.[5]

5. Single Leg Heel Raise Test [3][14][15][16][edit | edit source]

Aim: To determine the endurance of the calf musculature.[14]

Instruction: The dancer stands on one leg. They hold their other leg in a parallel coupé. The dancer is asked to perform as many relevés without plié as they can to a beat of 120 beats per minute (i.e. 30 heel raises per minute). The test is ended if the dancer can no longer keep up with the beat or if they choose to stop. The test is also stopped if a dancer completes 75 relevés. Each side is tested and the total number of relevés are added together.[15]

This test can also be performed as follows: Posterior calf strength is measured by counting the number of parallel single-leg heel raises that the dancer can perform while maintaining the pre-test relevé height on a straight leg. A “pass” for this test has been defined as performing 20 or more heel raises.[2]

Remember: Batalden[16] notes that at least 90 degrees of plantar flexion is needed for the subtalar joint to lock en pointe, thus helping to avoid ankle ligament injuries. In their testing, Batalden[16] included dorsiflexion "with a standard of 15°".

Note: For 5 to 8 year olds, the mean number of repetitions in the heel raise test has been found to be 15.2 repetitions. The mean number of repetitions in 9 to 12 year olds is 27.7.[16]

6. Double Leg Lower Test[14][edit | edit source]

Aim: To objectively evaluate abdominal strength.[14]

Instruction: The dancer lies supine. Their pelvis is in a neutral position and both legs are flexed to 90 degrees at the hips, so that they are perpendicular to the testing surface. While keeping both knees extended, the dancer is asked to slower lower their legs to the testing surface. The assessor looks at pelvis stability and records the angle of the legs when the pelvis begins to tilt anteriorly. A strength grade is given based on this angle.[14]

Remember: This test is recorded as a pass if this angle is 45 degrees or less.[14]

Note: Watch for any biomechanical compensations further up the body.[5]

7. Modified “Romberg” Test[14][17][18][edit | edit source]

Aim: To determine proprioception and falls risk.[5]

Instruction: The dancer stands in a single-leg parallel stance. They cross their arms and close their eyes. A dancer passes this test if they can maintain this position for more than 30 seconds without: opening their eyes, touching the non-support foot down, or moving their stance foot.[14]

Please click on the link for more information on the Romberg Test.

8. Timed Plank Test[15][edit | edit source]

Aim: To assess core endurance and the ability to maintain a neutral pelvis position.[15]

Instruction: The dancer starts in a full plank position on their hands and toes. They must achieve proper pelvic alignment before the test can start. The assessor times how long the dancer can hold this position. The test ends when the dancer can no longer hold the pelvis in the correct position or drops to their knees. It is also stopped after five minutes.[15]

Note: Being able to keep the core still while maintaining a neutral pelvis is important for control and balance during barre and centre work.[15]

9. Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT)[3][18][edit | edit source]

Aim: To measure dynamic balance.[3]

Instruction: There are two versions of this test commonly used, both have links to pages describing the tests further. This course refers to a test known as the "Y Balance Test", in which the individual, balances on one leg and touches 3 different points on the floor with the non-weightbearing foot. The second test is referred to as the Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT), as pictured along side. in this test four strips of athletic tape are cut (each strip is 6-8 feet long). Two pieces are used to create a '+' while the other two strips are used to create an 'x', which is positioned on top of the '+', thus forming a star shape. Each strip must be separated by a 45 degree angle.[19] During the SEBT, the aim is to maintain single-leg stance while reaching the contralateral leg as far as possible along the points of the star.[19][20]

Remember: Complete the test in all required directions.

Guidelines from the International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS)[21][edit | edit source]

The IADMS provides the following guidelines for when to begin pointe training:[21]

- "Not before age 12.

- If the student is not anatomically sound (e.g., insufficient ankle and foot plantar flexion range of motion; poor lower extremity alignment), do not allow pointe work.

- If she is not truly pre-professional, discourage pointe training.

- If she has weak trunk and pelvic (“core”) muscles or weak legs, delay pointe work (and consider implementing a strengthening program).

- If the student is hypermobile in the feet and ankles, delay pointe work (and consider implementing a strengthening program).

- If ballet classes are only once a week, discourage pointe training.

- If ballet classes are twice a week, and none of the above applies, begin in the fourth year of training."

Ballet Terms Explained[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Altmann C, Roberts J, Scharfbillig R, Jones S. Readiness for en pointe work in young ballet dancers are there proven screening tools and training protocols for a population at increased risk of injury?. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2019 Mar 15;23(1):40-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Richardson M, Liederbach M, Sandow E. Functional criteria for assessing pointe-readiness. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2010 Sep 1;14(3):82-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 DeWolf A, McPherson A, Besong K, Hiller C, Docherty C. Quantitative measures utilized in determining pointe readiness in young ballet dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2018 Dec 1;22(4):209-17.

- ↑ Cantergi D, Moraes LR, Loss JF. Applications of Biomechanics Analysis in Dance. InScientific Perspectives and Emerging Developments in Dance and the Performing Arts 2021 (pp. 25-44). IGI Global.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Green-Smerdon M. Pre-Pointe Assessment Course. Plus. 2022.

- ↑ Russell JA. Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives. Open access journal of sports medicine. 2013;4:199.

- ↑ Glumm SA. Functional Performance Criteria to Assess Pointe Readiness in Youth Ballet Dancers.

- ↑ McCormack MC, Bird H, de Medici A, Haddad F, Simmonds J. The physical attributes most required in professional ballet: a Delphi study. Sports medicine international open. 2019 Jan;3(01):E1-5.

- ↑ Meck C, Hess RA, Helldobler R, Roh J. Pre-pointe evaluation components used by dance schools. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2004 Jun 1;8(2):37-42.

- ↑ Barreau X, Gil C, Thoreux P. Ballet. Injury and Health Risk Management in Sports 2020 (pp. 725-731). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- ↑ Willson JD, Dougherty CP, Ireland ML, Davis IM. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005 Sep 1;13(5):316-25.

- ↑ Hébert-Losier K, Wessman C, Alricsson M, Svantesson U. Updated reliability and normative values for the standing heel-rise test in healthy adults. Physiotherapy. 2017 Dec 1;103(4):446-52.

- ↑ Thomas KS. Functional eleve performance as it applies to heel-rises in performance-level collegiate dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2003 Dec 15;7(4):115-20.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 Richardson M, Liederbach M, Sandow E. Functional criteria for assessing pointe-readiness. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2010 Sep 1;14(3):82-8.

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 15.17 15.18 15.19 15.20 15.21 15.22 15.23 15.24 Hewitt S, Mangum M, Tyo B, Nicks C. Fitness testing to determine pointe readiness in ballet dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2016 Dec 15;20(4):162-7.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Batalden L. Pointe-Readiness Screening and Exercise for the Young Studio Dancer. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2020;32(1):48-50.

- ↑ Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Hoffman HJ, Sklare DA, Schubert MC. The modified Romberg Balance Test: normative data in US adults. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2011 Oct;32(8):1309.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ani KU, Ibikunle PO, Nwosu CC, Ani NC. Are the Current Balance Screening Tests in Dance Medicine Specific Enough for Tracking the Effectiveness of Balance-Related Injury Rehabilitation in Dancers? A Scoping Review. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2021 Dec 15;25(4):217-30.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Olmsted LC, Carcia CR, Hertel J, Shultz SJ. Efficacy of the star excursion balance tests in detecting reach deficits in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training. 2002 Oct;37(4):501.

- ↑ Plisky PJ, Gorman PP, Butler RJ, Kiesel KB, Underwood FB, Elkins B. The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. North American journal of sports physical therapy: NAJSPT. 2009 May;4(2):92.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Weiss DS, Rist RA, Grossman G. Guidelines for Initiating Pointe Training. Journal of Dance Medicine ci Science• Volunae. 2009;13(3):91.