General Overview of Osteoarthritis for Rehabilitation Professionals: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Shala Cunningham|Shala Cunningham]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Shala Cunningham|Shala Cunningham]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic health condition. It can cause pain, decreased function, poor sleep, decreased mental health and reduced quality of life.<ref name=":0">Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. [https://www.oarsijournal.com/article/S1063-4584(21)00886-4/fulltext Epidemiology of osteoarthritis]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Feb;30(2):184-95. </ref><ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Improving care for osteoarthritis: the forgotten chronic disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/docs/2022/oarsi_infographic_for_policymakers_2022_final.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024). </ref> It is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and mortality.<ref>Constantino de Campos G, Mundi R, Whittington C, Toutounji MJ, Ngai W, Sheehan B. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1759720X20981219 Osteoarthritis, mobility-related comorbidities and mortality: an overview of meta-analyses]. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Dec 25;12:1759720X20981219. </ref><ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Is osteoarthritis a series disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/images/2020/oarsi-20-final-oa-infographic-_revised_copyright.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).</ref> | Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic health condition. It can cause pain, decreased function, poor sleep, decreased mental health and reduced quality of life.<ref name=":0">Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. [https://www.oarsijournal.com/article/S1063-4584(21)00886-4/fulltext Epidemiology of osteoarthritis]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Feb;30(2):184-95. </ref><ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Improving care for osteoarthritis: the forgotten chronic disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/docs/2022/oarsi_infographic_for_policymakers_2022_final.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024). </ref> It is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and mortality.<ref>Constantino de Campos G, Mundi R, Whittington C, Toutounji MJ, Ngai W, Sheehan B. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1759720X20981219 Osteoarthritis, mobility-related comorbidities and mortality: an overview of meta-analyses]. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Dec 25;12:1759720X20981219. </ref><ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Is osteoarthritis a series disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/images/2020/oarsi-20-final-oa-infographic-_revised_copyright.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).</ref> Conservative management strategies for osteoarthritis include education, exercise and weight management. This page provides an overview of osteoarthritis, including epidemiology, risk factors and pathology, before considering diagnosis and management trends. | ||

== Definition == | == Definition == | ||

<blockquote>The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) defines osteoarthritis as: “a disorder involving movable joints characterized by cell stress and extracellular matrix degradation initiated by micro- and macro-injury that activates maladaptive repair responses including pro-inflammatory pathways of innate immunity. The disease manifests first as a molecular derangement (abnormal joint tissue metabolism) followed by anatomic, and/or physiologic derangements (characterized by cartilage degradation, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, joint inflammation and loss of normal joint function), that can culminate in illness.”<ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Standardization of osteoarthritis definitions. Available from: https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions (last accessed 13 May 2024).</ref></blockquote>'''Key | <blockquote>The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) defines osteoarthritis as: “a disorder involving movable joints characterized by cell stress and extracellular matrix degradation initiated by micro- and macro-injury that activates maladaptive repair responses including pro-inflammatory pathways of innate immunity. The disease manifests first as a molecular derangement (abnormal joint tissue metabolism) followed by anatomic, and/or physiologic derangements (characterized by cartilage degradation, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, joint inflammation and loss of normal joint function), that can culminate in illness.”<ref>Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Standardization of osteoarthritis definitions. Available from: https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions (last accessed 13 May 2024).</ref></blockquote>'''Key point:'''<ref>Coaccioli S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Zis P, Rinonapoli G, Varrassi G. [https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/20/6013 Osteoarthritis: new insight on its pathophysiology]. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 12;11(20):6013. </ref> | ||

* osteoarthritis has traditionally been described as a degenerative cartilage disease, but our understanding has evolved and we know that there is a breakdown of the cartilage, as well as structural changes across the whole joint | * osteoarthritis has traditionally been described as a degenerative cartilage disease, but our understanding has evolved and we now know that there is a breakdown of the cartilage, as well as structural changes across the whole joint | ||

== Epidemiology == | == Epidemiology == | ||

According to the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, 595 million people had osteoarthritis in 2020 (i.e. 7.6% of the global population).<ref name=":9">GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10477960/ Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021]. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 Aug 21;5(9):e508-e522. </ref> This number has increased by 132.2% since 1990. These figures are expected to continue to increase. By 2050, cases of knee osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 74.9%, cases of hip osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 78.6%, cases of hand osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 48.6% and cases of other types of osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 95.1%.<ref name=":9" /> | |||

Increased prevalence has been linked to ''ageing'' populations and an increase in ''obesity'' and ''joint injuries''.<ref name=":1">He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, Ocasio-Nieves BD, Yocum L, Lin H, Tuan RS. [https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/9/8/194 Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: risk factors, regulatory pathways in chondrocytes, and experimental models]. Biology (Basel). 2020 Jul 29;9(8):194. </ref><ref name=":3">Van Doormaal MCM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Peter WF. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020 Dec;18(4):575-95. </ref> | |||

== Risk Factors == | == Risk Factors == | ||

Known risk factors for osteoarthritis include ageing, obesity, acute trauma, chronic overload, gender and hormone profile, metabolic syndrome, genetic predisposition<ref name=":1" /> and the gut-joint axis.<ref name=":8">Yunus MHM, Nordin A, Kamal H. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7696673/ Pathophysiological perspective of osteoarthritis]. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Nov 16;56(11):614. </ref> However, osteoarthritis is not "the inevitable consequence of these factors [...and…] different risk factors may act together in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis".<ref name=":1" /> | |||

'''Ageing''' is characterised by progressive tissue loss and decreased organ function, and it "represents the single greatest risk factor for OA"<ref name=":1" /> | '''Ageing''' is characterised by progressive tissue loss and decreased organ function, and it "represents the single greatest risk factor for OA."<ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Obesity''' is considered "the most prevalent '''preventable''' risk factor for developing osteoarthritis"<ref name=":2">Batushansky A, Zhu S, Komaravolu RK, South S, Mehta-D'souza P, Griffin TM. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1063458421008803 Fundamentals of OA. An initiative of osteoarthritis and cartilage. Obesity and metabolic factors in OA]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Apr;30(4):501-15. </ref>: | '''Obesity''' is considered "the most prevalent '''preventable''' risk factor for developing osteoarthritis"<ref name=":2">Batushansky A, Zhu S, Komaravolu RK, South S, Mehta-D'souza P, Griffin TM. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1063458421008803 Fundamentals of OA. An initiative of osteoarthritis and cartilage. Obesity and metabolic factors in OA]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Apr;30(4):501-15. </ref>: | ||

| Line 26: | Line 25: | ||

* obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in both males and females, but the effect size is greater in females<ref name=":2" /> | * obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in both males and females, but the effect size is greater in females<ref name=":2" /> | ||

'''Acute trauma / joint injury''' are considered "potent | '''Acute trauma / joint injury''' are considered "potent" risk factors for osteoarthritis.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''Chronic overload''': | '''Chronic overload''': | ||

* various occupational ergonomic risk factors for osteoarthritis have been proposed, including force exertion, demanding | * various occupational ergonomic risk factors for osteoarthritis have been proposed, including force exertion, demanding postures, repetitive movements, hand-arm vibration, kneeling / squatting, lifting and climbing<ref>Hulshof CTJ, Pega F, Neupane S, Colosio C, Daams JG, Kc P, et al. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412020323047 The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury]. Environ Int. 2021 May;150:106349. </ref> | ||

** these risk factors can increase the risk of developing knee or hip osteoarthritis compared to no exposure | ** these risk factors can increase the risk of developing knee or hip osteoarthritis compared to no exposure | ||

** however, because the quality of evidence is currently low, there is "limited evidence of harmfulness" | ** however, because the quality of evidence is currently low, there is "limited evidence of harmfulness" | ||

* another systematic review found that physically demanding jobs (e.g. construction work, floor and bricklaying, fishing, farming, etc) are associated with increased risk of knee and hip osteoarthritis, and there may be a dose-response relationship<ref name=":0" /> | * another systematic review found that physically demanding jobs (e.g. construction work, floor and bricklaying, fishing, farming, etc) are associated with increased risk of knee and hip osteoarthritis, and there may be a dose-response relationship<ref name=":0" /> | ||

'''Gender and hormone profile''': there are gender differences in osteoarthritis across all joints (the cervical spine is one potential exception)<ref name=":0" /> | '''Gender and hormone profile''': there are gender differences in osteoarthritis across all joints (the cervical spine is one potential exception)<ref name=":0" /> with females more likely to develop osteoarthritis.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

''' | '''Anatomic factors (joint deformities)''': the shape of a joint can impact the development of osteoarthritis<ref name=":8" /> and certain variations in the shape of bones / joints have been associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== Pathology == | == Pathology of Osteoarthritis == | ||

<blockquote>Osteoarthritis is a "dynamic and complex process, involving inflammatory, mechanical, and metabolic factors that result in the inability of the articular surface to serve its function of absorbing and distributing the mechanical load through the joint that ultimately leads to joint destruction."<ref name=":1" /></blockquote> | <blockquote>Osteoarthritis is a "dynamic and complex process, involving inflammatory, mechanical, and metabolic factors that result in the inability of the articular surface to serve its function of absorbing and distributing the mechanical load through the joint that ultimately leads to joint destruction."<ref name=":1" /></blockquote>Osteoarthritis is typically characterised by:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4">Cunningham S. Osteoarthritis Course. Plus, 2024.</ref> | ||

Osteoarthritis is typically characterised by:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4">Cunningham S. Osteoarthritis Course. Plus, 2024.</ref> | |||

* degradation / destruction of the articular cartilage | * degradation / destruction of the articular cartilage | ||

| Line 49: | Line 46: | ||

* synovial inflammation | * synovial inflammation | ||

* secondary inflammation of periarticular structures | * secondary inflammation of periarticular structures | ||

However, the exact pathological mechanisms of osteoarthritis are still unknown. Changes within the whole joint structure are believed to be due to an interplay between various tissues in the osteochondral complex (e.g. adipose tissue, synovial tissue, ligaments, tendons, muscles),<ref name=":1" /> and there is increasing evidence that low-grade, chronic inflammation plays a part in osteoarthritis.<ref>De Roover A, Escribano-Núñez A, Monteagudo S, Lories R. Fundamentals of osteoarthritis: Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2023 Oct;31(10):1303-11.</ref><blockquote>It is a "heterogeneous disease that impacts all component tissues of the articular joint organ."<ref name=":1" /></blockquote> | |||

Please watch the following optional video if you want to learn more about the pathology of osteoarthritis:{{#ev:youtube|sUOlmI-naFs|300}}<ref>Osmosis from Elsevier. Osteoarthritis - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUOlmI-naFs [last accessed 13/05/2024]</ref> | |||

== Clinical Features == | == Clinical Features == | ||

The pathological changes and symptoms caused by osteoarthritis vary considerably in each person.<ref name=":1" /> But typical signs and symptoms associated with osteoarthritis include:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5">Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8225295/ Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review]. JAMA. 2021 Feb 9;325(6):568-78. </ref> | The pathological changes and symptoms caused by osteoarthritis vary considerably in each person.<ref name=":1" /> But typical signs and symptoms associated with osteoarthritis include:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5">Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8225295/ Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review]. JAMA. 2021 Feb 9;325(6):568-78. </ref><ref name=":10">Schiphof D, Runhaar J, Waarsing JH, van Spil WE, van Middelkoop M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. [https://www.oarsijournal.com/article/S1063-4584(18)30791-X/fulltext The clinical and radiographic course of early knee and hip osteoarthritis over 10 years in CHECK (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee)]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Oct;27(10):1491-1500.</ref> | ||

* decreased range of motion | * decreased range of motion | ||

| Line 61: | Line 59: | ||

* crepitus | * crepitus | ||

* decreased mobility and functional limitations | * decreased mobility and functional limitations | ||

* reduced / loss of ability to engage in “valued activities”, | * reduced / loss of ability to engage in “valued activities”, such as walking, sports, dancing, etc. | ||

* bony tenderness | |||

== Diagnosis == | == Diagnosis == | ||

Osteoarthritis can be confirmed radiographically on x-ray. Radiographic findings include:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> | Osteoarthritis can be confirmed radiographically on x-ray. Radiographic findings include:<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> | ||

| Line 73: | Line 69: | ||

* cyst formation | * cyst formation | ||

* abnormalities of bone contour | * abnormalities of bone contour | ||

* ankylosis | * ankylosis | ||

<blockquote>However, x-rays can "underestimate the joint tissue involvement in OA, since they only visualize a component of the condition including cartilage loss that result in joint space narrowing and bony changes that result in subchondral sclerosis, cysts, and osteophyte formation. Once these changes are apparent on radiographs, the condition has significantly advanced."<ref name=":8" /></blockquote> | |||

=== Clinical vs Radiographic Osteoarthritis === | === Clinical vs Radiographic Osteoarthritis === | ||

==== '''Knee Osteoarthritis''' ==== | ===== '''Knee Osteoarthritis''' ===== | ||

Radiographic knee osteoarthritis requires structural changes on x-ray while clinical knee osteoarthritis is diagnosed based on a patient’s symptoms and the clinical examination.<ref name=":6">Törnblom M, Bremander A, Aili K, Andersson MLE, Nilsdotter A, Haglund E. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/14/3/e081999 Development of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and the associations to radiographic changes and baseline variables in individuals with knee pain: a 2-year longitudinal study]. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 8;14(3):e081999.</ref> | Radiographic knee osteoarthritis requires structural changes on x-ray while clinical knee osteoarthritis is diagnosed based on a patient’s symptoms and the clinical examination.<ref name=":6">Törnblom M, Bremander A, Aili K, Andersson MLE, Nilsdotter A, Haglund E. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/14/3/e081999 Development of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and the associations to radiographic changes and baseline variables in individuals with knee pain: a 2-year longitudinal study]. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 8;14(3):e081999.</ref> Radiography "is disputed because structural findings appear relatively late in the course of the disease and symptoms are not always associated with the structural findings."<ref name=":6" /> | ||

There are different clinical classification criteria used to help identify individuals with osteoarthritis, including the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical classification criteria.<ref name=":11">Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1063458419312099 Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020 Feb;28(2):167-72.</ref> For more information on these criteria, please see [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1063458419312099 Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care].<ref name=":11" /> | |||

The following clinical criteria for knee osteoarthritis are based on the NICE guidelines:<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":12">National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management: NICE Guideline [NG226]. 2022. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226 [Accessed 14th May 2024].</ref> | |||

* aged ≥ 45 years | |||

* has movement-related joint pain | |||

** | * has no knee morning stiffness or has knee morning stiffness that lasts ≤ 30 minutes | ||

==== Hip Osteoarthritis ==== | ===== Hip Osteoarthritis ===== | ||

Hip osteoarthritis has traditionally been diagnosed based on radiographic features, like the Kellgren and Lawrence score, but many guidelines recommend against using radiography as a diagnostic tool.<ref name=":7">Runhaar J, Özbulut Ö, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA; CREDO expert group. [https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/60/11/5158/6134093?login=false Diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis: first steps, based on the CHECK study]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5158-64. </ref> | Hip osteoarthritis has traditionally been diagnosed based on radiographic features, like the Kellgren and Lawrence score, but many guidelines recommend against using radiography as a diagnostic tool.<ref name=":7">Runhaar J, Özbulut Ö, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA; CREDO expert group. [https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/60/11/5158/6134093?login=false Diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis: first steps, based on the CHECK study]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5158-64. </ref> While there is no validated diagnostic criteria for ''early'' hip osteoarthritis,<ref name=":7" /> the American College of Rheumatology clinical classification criteria for hip osteoarthritis are as follows:<ref>Altman R, Alarcón G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.1780340502 The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip]. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 May;34(5):505-14. </ref><ref name=":10" /> | ||

* hip pain in combination with: | |||

** <15° of hip internal rotation | |||

** erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of ≤45 mm/hour OR ≤115° of hip flexion (a hip flexion measurement is used if ESR is not obtained) | |||

'''Or''' | |||

* hip pain and: | |||

** aged >50 years | |||

** ≥15° of hip internal rotation | |||

** pain with internal rotation | |||

** ≤60 minutes of morning stiffness | |||

===== Spine Osteoarthritis ===== | |||

Specific clinical criteria for identifying spine osteoarthritis (e.g. pain, morning stiffness, painful / reduced range of motion) are not yet available, but there is a known link between these criteria and lumbar disc degeneration.<ref>Van den Berg R, Chiarotto A, Enthoven WT, de Schepper E, Oei EHG, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877065720301536 Clinical and radiographic features of spinal osteoarthritis predict long-term persistence and severity of back pain in older adults]. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022 Jan;65(1):101427. </ref> | |||

===== Hand Osteoarthritis ===== | |||

The American College of Rheumatology criteria for osteoarthritis of the hand is as follows:<ref>Kloppenburg M, Stamm T, Watt I, Kainberger F, Cawston TE, Birrell FN, et al. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955144/#:~:text=Box%201%3A%20American%20College%20of,swelling%20in%20%E2%A9%BD2%20joints Research in hand osteoarthritis: time for reappraisal and demand for new strategies. An opinion paper]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Sep;66(9):1157-61. </ref> | |||

* | * hand pain, aching or stiffness on most days of the previous month, and three of the following four criteria: | ||

** | ** hard tissue enlargement of ≥ of 10 selected hand joints | ||

** | ** metacarpophalangeal joint swelling in ≤ joints | ||

** | ** enlargement of the hard tissue of ≥2 of the distal interphalangeal joints | ||

** | ** deformity of ≥1 of 10 selected hand joints | ||

==== | ===== Outcome Measures ===== | ||

There are | There are a range of outcome measures for osteoarthritis. Please see [[Osteoarthritis#Outcome Measures|here]] for more information. | ||

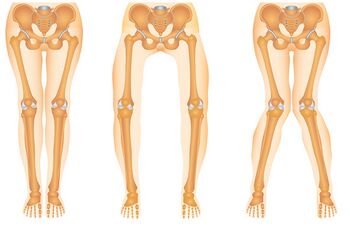

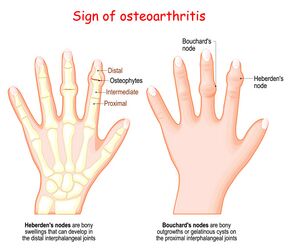

== Joint Deformities == | == Joint Deformities == | ||

| Line 116: | Line 119: | ||

* Bouchard's nodes | * Bouchard's nodes | ||

* genu varus/ valgus | * genu varus/ valgus | ||

<gallery widths="350px" heights="250px"> | |||

File:Anatomical Variatons of the Knee - Genu Varum and Genu Valgum.jpg|Figure 1. From left to right: knee with normal alignment, genu varus and genu valgus. | |||

File:Heberden's and Bouchard's Nodes - Shutterstock - ID 1781524226.jpg|Figure 2. Heberden's and Bouchard's nodes. </gallery> | |||

== Osteoarthritis Management == | |||

<blockquote>"Clinical guidelines for management of knee OA emphasise non-drug non-surgical strategies that focus on self-help and patient-driven options rather than clinician-delivered passive therapies."<ref name=":14">Hinman RS, Kimp AJ, Campbell PK, Russell T, Foster NE, Kasza J, et al. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7413018/ Technology versus tradition: a non-inferiority trial comparing video to face-to-face consultations with a physiotherapist for people with knee osteoarthritis. Protocol for the PEAK randomised controlled trial]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Aug 7;21(1):522.</ref></blockquote>General management goals include:<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* maintaining / gaining range of motion | |||

* increasing muscular support | |||

* decreasing joint stress | |||

* managing pain | |||

Medical management may include:<ref name=":4" /> | |||

* medication, including anti-inflammatories<ref name=":12" /> | |||

* weight management | |||

* intra-articular corticosteroid injections<ref name=":12" /> | |||

* surgical intervention (i.e. total joint replacement) | |||

** please note that the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) has "published moderate recommendations against using joint lavage and debridement as a treatment for symptomatic OA"<ref>Gress K, Charipova K, An D, Hasoon J, Kaye AD, Paladini A, et al. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1521689620300471 Treatment recommendations for chronic knee osteoarthritis]. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Sep;34(3):369-82. </ref> | |||

=== Physiotherapy Management === | |||

<blockquote>"The clinical effect of PT [physical therapy] on pain and disability in hip or knee OA is substantial, while its associated costs are low."<ref name=":3" /></blockquote>Key physiotherapy interventions for the hip and knee include patient education and exercise rehabilitation.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

===== Patient Education ===== | |||

Patient education topics might include:<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":12" /> | |||

* information about osteoarthritis | |||

* benefits of exercise and strengthening / healthy lifestyle / weight management (these conversations may vary depending on your scope of practice and may require referral to another health professional) | |||

* treatment options, as well as benefits and risks to ensure informed consent | |||

* if arthroplasty (joint replacement) is planned, physiotherapists might provide information on rehabilitation timeframes, assistive devices, benefits of prehabilitation (i.e. maintaining strength and fitness pre-operatively), post-operative considerations, lifestyle restrictions and any precautions that may be necessary | |||

===== Exercise Rehabilitation ===== | |||

Exercise rehabilitation should focus on joint-specific and general exercise / physical activity. Exercise programmes should be individualised for each person's goals, requirements and preferences. The following sections provide some general advice based on recent research for hip and knee osteoarthritis. | |||

'''Knee osteoarthritis''': A Cochrane review from 2015 looked at '''any''' land-based therapeutic exercise programmes for individuals with knee osteoarthritis, regardless of content, duration, frequency or intensity of the exercise programme, and found that: "any type of exercise programme that is performed regularly and is closely monitored can improve pain, physical function and quality of life related to knee OA in the short term."<ref>Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. [https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/24/1554 Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review]. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Dec;49(24):1554-7.</ref> | |||

'''Hip osteoarthritis:''' A 2014 Cochrane review also found that '''any''' "land‐based therapeutic exercise programmes can reduce pain and improve physical function among people with symptomatic hip OA."<ref>Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. [https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2/full Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 22;2014(4):CD007912. </ref> The programmes from the included studies were either performed independently or supervised.<ref>Poquet N, Williams M, Bennell KL. [https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/96/11/1689/2870028 Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip]. Phys Ther. 2016 Nov;96(11):1689-94. </ref> | |||

The following table provides a summary of Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type (FITT) principles for hip and knee osteoarthritis, based on recent research. Most of the information is adapted from Van Doormaal et al. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/msc.1492 A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis].<ref name=":3" /> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+Table 1. Frequency, Intensity, Time and Type (FITT) Principles for hip and knee osteoarthritis.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":13" /><ref name=":14" /> | |||

!FITT principle | |||

!Exercise recommendations | |||

|- | |||

|Frequency | |||

|Aim for at least 2 days per week of strengthening and 5 days of aerobic exercise | |||

* please note that for knee osteoarthritis, Husted et al.<ref name=":13">Husted RS, Troelsen A, Husted H, Grønfeldt BM, Thorborg K, Kallemose T, et al. K[https://www.oarsijournal.com/article/S1063-4584(22)00715-4/fulltext nee-extensor strength, symptoms, and need for surgery after two, four, or six exercise sessions/week using a home-based one-exercise program: a randomized dose-response trial of knee-extensor resistance exercise in patients eligible for knee replacement (the QUADX-1 trial)]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Jul;30(7):973-86. </ref> found that 2 sessions of strength training per week produce the same strength improvements as four or six sessions, but two sessions are better for pain and function (this may be due to the increased recovery time associated with two sessions compared to four or six) | |||

|- | |||

|Intensity | |||

|Muscle strength training: | |||

* aim for 60-80% of one repetition maximum (1RM) or 50-60% 1RM for individuals who aren't used to strength training | |||

* the PEAK (Physiotherapy Exercise and Physical Activity for Knee Osteoarthritis) study recommends that participants work hard or very hard<ref name=":14" /> | |||

* Van Doormaal et al.<ref name=":3" /> recommend: | |||

** 2-4 sets | |||

** 8-15 repetitions | |||

** 30-60 seconds rest between sets | |||

Aerobic training: | |||

* aim for more than 60% maximum heart rate (HRMax) or 40-60% for individuals who aren't used to aerobic exercise<ref name=":14" /> | |||

* slowly build up intensity | |||

* it is possible to use an activity tracker to establish a patient's baseline and build up from here<ref name=":14" /> | |||

|- | |||

|Type | |||

|Aim for a combination of strength, aerobic and functional training | |||

Strength exercises: | |||

* target large muscles around the knee and hip joints (e.g. knee extensors, hip abductors, knee flexors) | |||

** the strengthening exercises used in the PEAK study for knee osteoarthritis are listed [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7413018/table/Tab3/?report=objectonly here] | |||

* repeat on both sides | |||

* include functional exercises | |||

* the PEAK study for knee osteoarthritis recommends starting with three exercises (one quadriceps, one hip / gluteal, one hamstrings / gluteal), and increasing this to a maximum of six exercises in week two (two quadriceps, one hip / gluteal, one hamstrings / gluteal, one calf, one optional extra)<ref name=":14" /> | |||

Aerobic exercise: | |||

* low joint load exercises (e.g. walking, cycling, swimming, rowing, cross-trainer) | |||

Functional training: | |||

* focus on activities that a patient typically finds difficult in daily life (e.g. walking, stairs, transferring from sit to stand) | |||

Can also include balance, coordination, neuromuscular and range of motion exercises if indicated | |||

|- | |||

|Time | |||

| | |||

* 8-12 weeks of treatment, with one or more follow-up sessions (e.g. at 3 and 6 months post-treatment) | |||

* Encourage ongoing self-management and continued exercise | |||

|} | |||

The following videos include some ideas for exercises. The video on the left focuses on knee osteoarthritis and the video on the right demonstrates hip exercises. The strengthening exercises used in the PEAK study for knee osteoarthritis are listed [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7413018/table/Tab3/?report=objectonly here]. | |||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|Rl3OkKlftsI|250}} <div class="text-right"><ref>AskDoctorJo. Knee Osteoarthritis (OA) Stretches & Exercises - Ask Doctor Jo. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rl3OkKlftsI [last accessed 15/05/2023]</ref></div></div> | |||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|DrZw_G3trqU|250}} <div class="text-right"><ref>AskDoctorJo. Hip Arthritis Stretches & Exercises - Ask Doctor Jo. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrZw_G3trqU [last accessed 15/05/2024]</ref></div></div> | |||

</div> | |||

Key considerations for exercise rehabilitation:<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* include a warm-up / cool down | |||

* increase the intensity of training gradually (e.g. once per week) to the maximum level for the patient | |||

* reduce the intensity of the next session if joint pain increases after a workout and persists for more than 2 hours after | |||

* for patients who are untrained or limited by pain / mobility, start with short sessions (10 minutes or less) | |||

* offer alternatives to exercises | |||

===== Other Rehabilitation Interventions ===== | |||

Other interventions might include:<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":12" /> | |||

* manual therapy (should only be considered alongside therapeutic exercise<ref name=":12" />) | |||

* assistive mobility devices (e.g. walking sticks) for individuals with lower limb osteoarthritis | |||

* the NICE guidelines recommend against the routine use of insoles, braces, tape, splints or supports, unless:<ref name=":12" /> | |||

** there is evidence of joint instability or abnormal biomechanical loading AND | |||

** therapeutic exercise will not be effective or is not suitable without an aid or device being used AND | |||

** the aid or device will likely improve function / movement | |||

Please note that the NICE guidelines '''do not recommend''' the following treatments for individuals with osteoarthritis due to a lack of benefits:<ref name=":12" /> | |||

* acupuncture | |||

* transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) | |||

* ultrasound | |||

* interferential therapy | |||

* laser therapy | |||

* pulsed short-wave therapy | |||

* neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 01:11, 17 May 2024

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common chronic health condition. It can cause pain, decreased function, poor sleep, decreased mental health and reduced quality of life.[1][2] It is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and mortality.[3][4] Conservative management strategies for osteoarthritis include education, exercise and weight management. This page provides an overview of osteoarthritis, including epidemiology, risk factors and pathology, before considering diagnosis and management trends.

Definition[edit | edit source]

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) defines osteoarthritis as: “a disorder involving movable joints characterized by cell stress and extracellular matrix degradation initiated by micro- and macro-injury that activates maladaptive repair responses including pro-inflammatory pathways of innate immunity. The disease manifests first as a molecular derangement (abnormal joint tissue metabolism) followed by anatomic, and/or physiologic derangements (characterized by cartilage degradation, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, joint inflammation and loss of normal joint function), that can culminate in illness.”[5]

Key point:[6]

- osteoarthritis has traditionally been described as a degenerative cartilage disease, but our understanding has evolved and we now know that there is a breakdown of the cartilage, as well as structural changes across the whole joint

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

According to the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, 595 million people had osteoarthritis in 2020 (i.e. 7.6% of the global population).[7] This number has increased by 132.2% since 1990. These figures are expected to continue to increase. By 2050, cases of knee osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 74.9%, cases of hip osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 78.6%, cases of hand osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 48.6% and cases of other types of osteoarthritis are projected to increase by 95.1%.[7]

Increased prevalence has been linked to ageing populations and an increase in obesity and joint injuries.[8][9]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Known risk factors for osteoarthritis include ageing, obesity, acute trauma, chronic overload, gender and hormone profile, metabolic syndrome, genetic predisposition[8] and the gut-joint axis.[10] However, osteoarthritis is not "the inevitable consequence of these factors [...and…] different risk factors may act together in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis".[8]

Ageing is characterised by progressive tissue loss and decreased organ function, and it "represents the single greatest risk factor for OA."[8]

Obesity is considered "the most prevalent preventable risk factor for developing osteoarthritis"[11]:

- previously obesity was considered a primary risk factor in knee osteoarthritis because of its impact on biomechanics, but it is now understood that it increases risk by altering metabolism and inflammation[11]

- obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in various joints, including the hand,[12] hip, knee, ankle and spine[11]

- obesity increases the risk of osteoarthritis in both males and females, but the effect size is greater in females[11]

Acute trauma / joint injury are considered "potent" risk factors for osteoarthritis.[1]

Chronic overload:

- various occupational ergonomic risk factors for osteoarthritis have been proposed, including force exertion, demanding postures, repetitive movements, hand-arm vibration, kneeling / squatting, lifting and climbing[13]

- these risk factors can increase the risk of developing knee or hip osteoarthritis compared to no exposure

- however, because the quality of evidence is currently low, there is "limited evidence of harmfulness"

- another systematic review found that physically demanding jobs (e.g. construction work, floor and bricklaying, fishing, farming, etc) are associated with increased risk of knee and hip osteoarthritis, and there may be a dose-response relationship[1]

Gender and hormone profile: there are gender differences in osteoarthritis across all joints (the cervical spine is one potential exception)[1] with females more likely to develop osteoarthritis.[14]

Anatomic factors (joint deformities): the shape of a joint can impact the development of osteoarthritis[10] and certain variations in the shape of bones / joints have been associated with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.[1]

Pathology of Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis is a "dynamic and complex process, involving inflammatory, mechanical, and metabolic factors that result in the inability of the articular surface to serve its function of absorbing and distributing the mechanical load through the joint that ultimately leads to joint destruction."[8]

Osteoarthritis is typically characterised by:[8][14]

- degradation / destruction of the articular cartilage

- surface irregularities

- osteophyte formation

- subchondral bone remodelling / thickening

- synovial inflammation

- secondary inflammation of periarticular structures

However, the exact pathological mechanisms of osteoarthritis are still unknown. Changes within the whole joint structure are believed to be due to an interplay between various tissues in the osteochondral complex (e.g. adipose tissue, synovial tissue, ligaments, tendons, muscles),[8] and there is increasing evidence that low-grade, chronic inflammation plays a part in osteoarthritis.[15]

It is a "heterogeneous disease that impacts all component tissues of the articular joint organ."[8]

Please watch the following optional video if you want to learn more about the pathology of osteoarthritis:

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

The pathological changes and symptoms caused by osteoarthritis vary considerably in each person.[8] But typical signs and symptoms associated with osteoarthritis include:[8][14][17][18]

- decreased range of motion

- stiffness

- pain

- deformity

- crepitus

- decreased mobility and functional limitations

- reduced / loss of ability to engage in “valued activities”, such as walking, sports, dancing, etc.

- bony tenderness

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis can be confirmed radiographically on x-ray. Radiographic findings include:[8][14][17]

- joint space narrowing

- osteophytes

- subchondral sclerosis

- cyst formation

- abnormalities of bone contour

- ankylosis

However, x-rays can "underestimate the joint tissue involvement in OA, since they only visualize a component of the condition including cartilage loss that result in joint space narrowing and bony changes that result in subchondral sclerosis, cysts, and osteophyte formation. Once these changes are apparent on radiographs, the condition has significantly advanced."[10]

Clinical vs Radiographic Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Knee Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Radiographic knee osteoarthritis requires structural changes on x-ray while clinical knee osteoarthritis is diagnosed based on a patient’s symptoms and the clinical examination.[19] Radiography "is disputed because structural findings appear relatively late in the course of the disease and symptoms are not always associated with the structural findings."[19]

There are different clinical classification criteria used to help identify individuals with osteoarthritis, including the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical classification criteria.[20] For more information on these criteria, please see Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care.[20]

The following clinical criteria for knee osteoarthritis are based on the NICE guidelines:[20][21]

- aged ≥ 45 years

- has movement-related joint pain

- has no knee morning stiffness or has knee morning stiffness that lasts ≤ 30 minutes

Hip Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis has traditionally been diagnosed based on radiographic features, like the Kellgren and Lawrence score, but many guidelines recommend against using radiography as a diagnostic tool.[22] While there is no validated diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis,[22] the American College of Rheumatology clinical classification criteria for hip osteoarthritis are as follows:[23][18]

- hip pain in combination with:

- <15° of hip internal rotation

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of ≤45 mm/hour OR ≤115° of hip flexion (a hip flexion measurement is used if ESR is not obtained)

Or

- hip pain and:

- aged >50 years

- ≥15° of hip internal rotation

- pain with internal rotation

- ≤60 minutes of morning stiffness

Spine Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Specific clinical criteria for identifying spine osteoarthritis (e.g. pain, morning stiffness, painful / reduced range of motion) are not yet available, but there is a known link between these criteria and lumbar disc degeneration.[24]

Hand Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

The American College of Rheumatology criteria for osteoarthritis of the hand is as follows:[25]

- hand pain, aching or stiffness on most days of the previous month, and three of the following four criteria:

- hard tissue enlargement of ≥ of 10 selected hand joints

- metacarpophalangeal joint swelling in ≤ joints

- enlargement of the hard tissue of ≥2 of the distal interphalangeal joints

- deformity of ≥1 of 10 selected hand joints

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are a range of outcome measures for osteoarthritis. Please see here for more information.

Joint Deformities[edit | edit source]

Specific joint deformities to look out for:[14]

- Heberden's nodes

- Bouchard's nodes

- genu varus/ valgus

Osteoarthritis Management[edit | edit source]

"Clinical guidelines for management of knee OA emphasise non-drug non-surgical strategies that focus on self-help and patient-driven options rather than clinician-delivered passive therapies."[26]

General management goals include:[14]

- maintaining / gaining range of motion

- increasing muscular support

- decreasing joint stress

- managing pain

Medical management may include:[14]

- medication, including anti-inflammatories[21]

- weight management

- intra-articular corticosteroid injections[21]

- surgical intervention (i.e. total joint replacement)

- please note that the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) has "published moderate recommendations against using joint lavage and debridement as a treatment for symptomatic OA"[27]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

"The clinical effect of PT [physical therapy] on pain and disability in hip or knee OA is substantial, while its associated costs are low."[9]

Key physiotherapy interventions for the hip and knee include patient education and exercise rehabilitation.[9]

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

Patient education topics might include:[9][21]

- information about osteoarthritis

- benefits of exercise and strengthening / healthy lifestyle / weight management (these conversations may vary depending on your scope of practice and may require referral to another health professional)

- treatment options, as well as benefits and risks to ensure informed consent

- if arthroplasty (joint replacement) is planned, physiotherapists might provide information on rehabilitation timeframes, assistive devices, benefits of prehabilitation (i.e. maintaining strength and fitness pre-operatively), post-operative considerations, lifestyle restrictions and any precautions that may be necessary

Exercise Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Exercise rehabilitation should focus on joint-specific and general exercise / physical activity. Exercise programmes should be individualised for each person's goals, requirements and preferences. The following sections provide some general advice based on recent research for hip and knee osteoarthritis.

Knee osteoarthritis: A Cochrane review from 2015 looked at any land-based therapeutic exercise programmes for individuals with knee osteoarthritis, regardless of content, duration, frequency or intensity of the exercise programme, and found that: "any type of exercise programme that is performed regularly and is closely monitored can improve pain, physical function and quality of life related to knee OA in the short term."[28]

Hip osteoarthritis: A 2014 Cochrane review also found that any "land‐based therapeutic exercise programmes can reduce pain and improve physical function among people with symptomatic hip OA."[29] The programmes from the included studies were either performed independently or supervised.[30]

The following table provides a summary of Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type (FITT) principles for hip and knee osteoarthritis, based on recent research. Most of the information is adapted from Van Doormaal et al. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis.[9]

| FITT principle | Exercise recommendations |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Aim for at least 2 days per week of strengthening and 5 days of aerobic exercise

|

| Intensity | Muscle strength training:

Aerobic training: |

| Type | Aim for a combination of strength, aerobic and functional training

Strength exercises:

Aerobic exercise:

Functional training:

Can also include balance, coordination, neuromuscular and range of motion exercises if indicated |

| Time |

|

The following videos include some ideas for exercises. The video on the left focuses on knee osteoarthritis and the video on the right demonstrates hip exercises. The strengthening exercises used in the PEAK study for knee osteoarthritis are listed here.

Key considerations for exercise rehabilitation:[9]

- include a warm-up / cool down

- increase the intensity of training gradually (e.g. once per week) to the maximum level for the patient

- reduce the intensity of the next session if joint pain increases after a workout and persists for more than 2 hours after

- for patients who are untrained or limited by pain / mobility, start with short sessions (10 minutes or less)

- offer alternatives to exercises

Other Rehabilitation Interventions[edit | edit source]

Other interventions might include:[14][21]

- manual therapy (should only be considered alongside therapeutic exercise[21])

- assistive mobility devices (e.g. walking sticks) for individuals with lower limb osteoarthritis

- the NICE guidelines recommend against the routine use of insoles, braces, tape, splints or supports, unless:[21]

- there is evidence of joint instability or abnormal biomechanical loading AND

- therapeutic exercise will not be effective or is not suitable without an aid or device being used AND

- the aid or device will likely improve function / movement

Please note that the NICE guidelines do not recommend the following treatments for individuals with osteoarthritis due to a lack of benefits:[21]

- acupuncture

- transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- ultrasound

- interferential therapy

- laser therapy

- pulsed short-wave therapy

- neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Feb;30(2):184-95.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Improving care for osteoarthritis: the forgotten chronic disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/docs/2022/oarsi_infographic_for_policymakers_2022_final.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Constantino de Campos G, Mundi R, Whittington C, Toutounji MJ, Ngai W, Sheehan B. Osteoarthritis, mobility-related comorbidities and mortality: an overview of meta-analyses. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Dec 25;12:1759720X20981219.

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Is osteoarthritis a series disease infographic. Available from: https://oarsi.org/sites/oarsi/files/images/2020/oarsi-20-final-oa-infographic-_revised_copyright.pdf (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). Standardization of osteoarthritis definitions. Available from: https://oarsi.org/research/standardization-osteoarthritis-definitions (last accessed 13 May 2024).

- ↑ Coaccioli S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Zis P, Rinonapoli G, Varrassi G. Osteoarthritis: new insight on its pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 12;11(20):6013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 Aug 21;5(9):e508-e522.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, Ocasio-Nieves BD, Yocum L, Lin H, Tuan RS. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: risk factors, regulatory pathways in chondrocytes, and experimental models. Biology (Basel). 2020 Jul 29;9(8):194.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Van Doormaal MCM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Peter WF. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020 Dec;18(4):575-95.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Yunus MHM, Nordin A, Kamal H. Pathophysiological perspective of osteoarthritis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Nov 16;56(11):614.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Batushansky A, Zhu S, Komaravolu RK, South S, Mehta-D'souza P, Griffin TM. Fundamentals of OA. An initiative of osteoarthritis and cartilage. Obesity and metabolic factors in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Apr;30(4):501-15.

- ↑ Plotz B, Bomfim F, Sohail MA, Samuels J. Current epidemiology and risk factors for the development of hand osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021 Jul 3;23(8):61.

- ↑ Hulshof CTJ, Pega F, Neupane S, Colosio C, Daams JG, Kc P, et al. The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int. 2021 May;150:106349.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 Cunningham S. Osteoarthritis Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ De Roover A, Escribano-Núñez A, Monteagudo S, Lories R. Fundamentals of osteoarthritis: Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2023 Oct;31(10):1303-11.

- ↑ Osmosis from Elsevier. Osteoarthritis - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUOlmI-naFs [last accessed 13/05/2024]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2021 Feb 9;325(6):568-78.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Schiphof D, Runhaar J, Waarsing JH, van Spil WE, van Middelkoop M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. The clinical and radiographic course of early knee and hip osteoarthritis over 10 years in CHECK (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Oct;27(10):1491-1500.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Törnblom M, Bremander A, Aili K, Andersson MLE, Nilsdotter A, Haglund E. Development of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and the associations to radiographic changes and baseline variables in individuals with knee pain: a 2-year longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 8;14(3):e081999.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020 Feb;28(2):167-72.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management: NICE Guideline [NG226]. 2022. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226 [Accessed 14th May 2024].

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Runhaar J, Özbulut Ö, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA; CREDO expert group. Diagnostic criteria for early hip osteoarthritis: first steps, based on the CHECK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5158-64.

- ↑ Altman R, Alarcón G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 May;34(5):505-14.

- ↑ Van den Berg R, Chiarotto A, Enthoven WT, de Schepper E, Oei EHG, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Clinical and radiographic features of spinal osteoarthritis predict long-term persistence and severity of back pain in older adults. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022 Jan;65(1):101427.

- ↑ Kloppenburg M, Stamm T, Watt I, Kainberger F, Cawston TE, Birrell FN, et al. Research in hand osteoarthritis: time for reappraisal and demand for new strategies. An opinion paper. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Sep;66(9):1157-61.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Hinman RS, Kimp AJ, Campbell PK, Russell T, Foster NE, Kasza J, et al. Technology versus tradition: a non-inferiority trial comparing video to face-to-face consultations with a physiotherapist for people with knee osteoarthritis. Protocol for the PEAK randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Aug 7;21(1):522.

- ↑ Gress K, Charipova K, An D, Hasoon J, Kaye AD, Paladini A, et al. Treatment recommendations for chronic knee osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Sep;34(3):369-82.

- ↑ Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Dec;49(24):1554-7.

- ↑ Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 22;2014(4):CD007912.

- ↑ Poquet N, Williams M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Phys Ther. 2016 Nov;96(11):1689-94.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Husted RS, Troelsen A, Husted H, Grønfeldt BM, Thorborg K, Kallemose T, et al. Knee-extensor strength, symptoms, and need for surgery after two, four, or six exercise sessions/week using a home-based one-exercise program: a randomized dose-response trial of knee-extensor resistance exercise in patients eligible for knee replacement (the QUADX-1 trial). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022 Jul;30(7):973-86.

- ↑ AskDoctorJo. Knee Osteoarthritis (OA) Stretches & Exercises - Ask Doctor Jo. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rl3OkKlftsI [last accessed 15/05/2023]

- ↑ AskDoctorJo. Hip Arthritis Stretches & Exercises - Ask Doctor Jo. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrZw_G3trqU [last accessed 15/05/2024]