Paediatric Lower Extremity Torsional Conditions

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Paediatric lower extremity and gait concerns are common reasons for visits to paediatricians and therapy services.[1][2][3][4][5] They can account for up to 16% of all new paediatric orthopaedic surgeon referrals.[6] Parents commonly worry about in- or out-toeing or that their child might be delayed in meeting developmental milestones because of lower extremity or gait conditions.[1] [2][4] In-toeing typically resolves with skeletal maturity. However, out-toeing can be a more persistent condition.[6] It is, therefore, important that rehabilitation professionals understand typical and atypical lower extremity development and when to initiate a referral to a paediatrician or orthopaedic surgeon.

Torsion of the lower extremity can be the "summation of anatomic axial (transverse) plane tilt or twist between the ends of the bones, capsular laxity or tightness, and muscular control during growth."[2]

This article summarises the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and assessment of lower extremity torsional conditions and basic interventions.

Torsional Conditions[edit | edit source]

Femoral Torsion[edit | edit source]

In newborns, internal femoral torsion of up to 40° can be considered typical. External femoral torsion can also be prominent and considered typical at birth.[7]

Special topic: what is the difference between femoral torsion and femoral version?[edit | edit source]

Version and torsion are not identical conditions, but they may both occur at the same time.[3][8]

Torsion is a "structural, osseous state of twist in a bone along its longitudinal axis."[8]

- Femoral antetorsion (medial femoral torsion): when the femur has a medial twist of the distal-on-proximal ends.

- Femoral retrotorsion (lateral femoral torsion): a deformity that ranges from a lack of typical femoral medial torsion to a true lateral twist of the distal-on-proximal ends of the femur.

Version describes "a position in space relative to a plane"[8] of motion and refers to the rotation of the neck of the femur in relation to the femoral condyles at the level of the knee.[3]

- Femoral anteversion: decreased angle between the neck of the femur and the femoral condyles. Normal anteversion of the femoral neck is approximately 15°. Femoral anteversion is more common than femoral retroversion.[3]

- Femoral retroversion: increased angle between the neck of the femur and the femoral condyles.[3]

Tibial Torsion[edit | edit source]

- Internal tibial torsion is common in children aged under four years old.

- It typically presents as internal rotation of the tibia and in-toeing gait.

- It often resolves spontaneously by four years of age; less than 1% of torsional deformities fail to resolve in childhood.

- Tibial torsions (especially external tibial torsion) are often associated with (1) increased incidence of knee osteoarthritis later in life and (2) increased incidence of osteochondritis dissecans. They can also be a predisposing factor for (3) Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in male athletes.[3]

What is the Source of the Rotation?[edit | edit source]

Some mild in-toeing and out-toeing can occur in typically developing children. Therefore, it is important to differentiate between typical and atypical as part of the lower extremity assessment. If in- or out-toeing is found to be atypical, the next step is to determine which components of the lower extremity are the source of the torsional condition and intervene at that level.[3]

Components that can contribute to in-toeing:

- femoral anteversion

- internal tibial rotation

- metatarsus adductus

Components that can contribute to out-toeing:

- external rotation contractures of the hip

- femoral retroversion (rare)

- external tibial rotation

- calcaneovalgus

Rehabilitation Examination for Torsional Conditions[edit | edit source]

Past Medical History[edit | edit source]

The evaluation / subjective interview for torsional conditions is similar to those for most lower extremity orthopaedic concerns.[3] It should cover the following areas:

- child's birth history (premature versus full term)

- orthopaedic or neurological concerns

- developmental milestone history or concerns

- child's age when in or out-toeing was first observed

- significant family history, especially torsional or orthopaedic conditions

- previous interventions

- the child's common sleeping and sitting positions

- when the child started to walk independently and how long they have been walking

Clinical pearl: can a child's sitting and sleeping positions exacerbate torsional conditions?[edit | edit source]

Literature reviews have identified certain "myths in pediatric orthopedics" surrounding topics such as in and out-toeing, W-sitting, and toe-walking. These are common positions/conditions and can be examples of normal variations in growth and development in young children.[9] Honig et al.[9] note the following:

- "Femoral and tibial torsion typically improve in the first 10–14 years of life."[9]

- "W-sitting is a comfortable seating position for children with femoral anteversion[3] [9] and increased internal hip rotation. W-sitting does not cause hip dysplasia, nor is there evidence to support the concern that it may cause future functional deficits."[9]

However, positions like W-sitting can exacerbate femoral anteversion for a small percentage of patients. This is due to the ground reaction forces created by this position. This is a significant factor to consider because, in the early modelling stages of development, the hip is "being modelled based on these ground reaction forces".[3]

A referral is warranted if the patient exhibits moderate to severe deformity, lack of resolution or worsening with time, pain, or functional impairments.[9][5]

Physical Assessment[edit | edit source]

The general assessment should include:[3]

- range of motion (ROM) testing

- strength testing

- tone assessment

- balance testing

- gait analysis and functional movement assessment

- general appearance of the limb to rule out concerns beyond orthopaedic issues, such as muscle atrophy, oedema, erythema, or a difference in temperature between the lower limbs

When assessing for sources of torsional conditions, it is important to consider factors that could affect the alignment of the lower quarter.[3]

Foot progression angle (FPA): the angular difference between the axis of the foot and the line of progression during gait (see image).[3]

- In-toeing is expressed as a negative value

- Out-toeing is expressed as a positive value

- FPA is variable during infancy

- Mean value in children: +10° (range -3 to +2-)

- Severity of in-toeing in children:

- mild: −5° to −10°

- moderate: −10° to −15°

- severe: more than −15°

Femoral version: rotation of the neck of the femur in relation to the femoral condyles at the level of the knee. At times, femoral version is combined with femoral torsion (a physical torsion or twist in the shaft of the femur). Femoral torsion will also cause a change in the angle between the neck of the femur and the femoral condyles.[3]

- Craig's test: also known as the Trochanteric Prominence Angle Test. Craig's test is a passive test that is used to measure femoral anteversion or forward torsion of the femoral neck.[10] Craig's test is described in detail here.

Hip rotation range of motion [3]

- Lateral hip rotation (LHR): also known as external rotation of the hip. Femoral retroversion is indicated by increased external rotation compared to internal rotation.

- Medial hip rotation (MHR): also known as internal rotation of the hip. Femoral anteversion is indicated by increased internal rotation compared to external rotation.

Thigh-foot angle (TFA): a means to measure tibial torsion.[3]

- To measure internal or external tibial torsion, the patient is positioned in prone lying with their knees flexed to 90° and foot resting in its natural position. The TFA is measured between the line bisecting the posterior thigh and another line bisecting the foot:[11]

- normal TFA is between 0° to 30°

- external tibial torsion is a TFA of more than 30°

- internal tibial torsion is a TFA of less than 0°

Transmalleolar axis (TMA): another way to measure tibial torsion.[3]

- To measure internal or external tibial torsion, the patient is positioned in prone lying with their knees flexed to 90°. Their ankle is in neutral, and the sole of their foot is parallel to the floor. The TMA is measured between the line bisecting the longitudinal axis of the thigh and the line perpendicular to the axis between the most prominent portions of the medial and lateral malleolus.[12]

Forefoot alignment[3]: there is a significant relationship between the forefoot angle and the positioning of the rearfoot. The relationship of the forefoot to rearfoot is measured to quantify forefoot varus or forefoot valgus.[13]

- To measure the relationship, the patient is positioned in prone lying with figure ‘4’ position for the non-examined lower extremity, the patient's foot is place in subtalar neutral. Forefoot alignment is measured by placing the stationary arm of a goniometer perpendicular to an imaginary line bisecting calcaneus with the fulcrum on the point bisecting calcaneus. The movable arm of the goniometer is placed parallel to an imaginary line passing through metatarsal heads.

- Forefoot angle of 0° is considered neutral

- Positive degree is forefoot varus

- Negative degree is forefoot valgus[13]

Other Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

- X-ray imaging

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Bone scans

- Laboratory tests such as blood work[3]

Treatment Options for Torsional Conditions[edit | edit source]

Femoral Anteversion Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

Bracing with strapping and compression:

- e.g. TheraTogs

- Can improve gait quality when wearing the device, but there is a lack of evidence-based support. Carryover and consistency with wearing the device outside the clinic are vital for long-time positive outcomes.

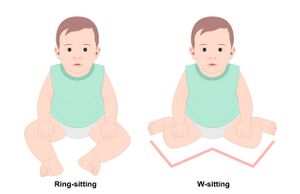

Encourage ring-sitting and avoid/discourage W-sitting. Ring-sitting is similar to tailor sitting (or criss-cross sitting). In both positions, the child is sitting supported on their backside, hips ABDucted and externally rotated, knees flexed to bring their feet toward each other. This creates a wide and stable base of support in sitting. Ring-sitting involves the feet facing or touching on their plantar surfaces, while tailor sitting has the feet crossed one over the other.

Surgical correction: femoral denotation osteotomy is considered if significant femoral anteversion is still present in children aged 10 to 14 years. This is a highly invasive surgery and should only be considered if the child is tripping a lot, having falls, if there are safety concerns, if the child is unable to keep up with their peers, has severe hip and / or knee pain, or is showing signs of femoral acetabular impingement.

Tibial Torsion Treatment[edit | edit source]

Tibial torsion can occur as part of typical development, but a small percentage of children do not improve, which can result in significant functional deficits.[3]

Oberservation: as most cases of tibial torsion resolve spontaneously by the age of four years.

Splinting and/or bracing: if internal tibial torsion is persistant after 18 months of age, could consider trying orthotics or shoes for around six months.[3]

- Friedman counter splint: a dynamic splint consisting of a belt around the posterior heels which allows for motion in all planes except internal rotation.[14]

- Denis Browne bar: a bar is attached to the soles of the child's shoes. It is used to treat metatarsus adductus, convex pes planovalgus, and positional abnormalities of the leg.[14]

- Wheaton brace: similar in appearance to an ankle foot orthosis (AFO), but it has a medial flare to abduct the forefoot. It can be used as an alternative to serial casting for the treatment of metatarsus adductus.[14]

Surgical correction: external rotational osteotomy of the tibia and fibula. Surgical management can be indicated for children who are aged more than six to eight years and who have functional issues and a thigh-foot angle of more than 15°.[3]

Optional Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

- Biomechanical Assessment of Foot and Ankle

- Craig's Test

- Gait Development in the Growing Child

- Gross Motor Milestones in Infants 0-14 Months

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kahf H, Kesbeh Y, van Baarsel E, Patel V, Alonzo N. Approach to pediatric rotational limb deformities. Orthopedic Reviews. 2019 Sep 9;11(3).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 BMJ Best Practice. Torsion of the Lower Limb in Children. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/748 (accessed 14/October/2023).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 Eskay K. Paediatric Physiotherapy Programme. Paediatric Lower Extremity Torsional Conditions Course. Plus, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cao LA, Wimberly L. When to Be Concerned About Abnormal Gait: Toe Walking, In-Toeing, Out-Toeing, Bowlegs, and Knock-Knees. Pediatric Annals. 2022 Sep 1;51(9):e340-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kainz H, Mindler GT, Kranzl A. Influence of femoral anteversion angle and neck-shaft angle on muscle forces and joint loading during walking. Plos one. 2023 Oct 12;18(10):e0291458.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Chandrananth J, Hannan R, Bouton D, Raney E, Sienko S, Do P, Bauer JP. The Effects of Lower Extremity Rotational Malalignment on Pediatric Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement and Information System (PROMIS) Scores. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2022 Sep;42(8):e889.

- ↑ Merck Manual. Femoral Torsion (Twisting). Available from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/congenital-craniofacial-and-musculoskeletal-abnormalities/femoral-torsion-twisting (accessed 24 October 2023).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Cusick BD, Stuberg WA. Assessment of lower-extremity alignment in the transverse plane: implications for management of children with neuromotor dysfunction. Physical therapy. 1992 Jan 1;72(1):3-15.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Honig EL, Haeberle HS, Kehoe CM, Dodwell ER. Pediatric orthopedic mythbusters: the truth about flexible flatfeet, tibial and femoral torsion, W-sitting, and idiopathic toe-walking. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2021 Feb 1;33(1):105-13.

- ↑ Scorcelletti M, Reeves ND, Rittweger J, Ireland A. Femoral anteversion: significance and measurement.Journal of Anatomy. 2020 Nov;237(5):811-26.

- ↑ Stuberg W, Temme J, Kaplan P, Clarke A, Fuchs R. Measurement of tibial torsion and thigh-foot angle using goniometry and computed tomography. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1991 Nov 1;272:208-12.

- ↑ Lee SH, Chung CY, Park MS, Choi IH, Cho TJ. Tibial torsion in cerebral palsy: validity and reliability of measurement. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2009 Aug;467:2098-104.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Buchanan KR, Davis I. The relationship between forefoot, midfoot, and rearfoot static alignment in pain-free individuals. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2005 Sep;35(9):559-66.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Musculoskeletal Key. Pediatrics. Available from: https://musculoskeletalkey.com/pediatrics-8/ (accessed 25 October 2023).