Management of Lower Back Pain related to Lower Cross Syndrome (LCS)

Lower Cross Syndrome[edit | edit source]

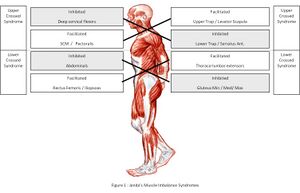

Lower Crossed Syndrome (LCS) is a musculoskeletal condition characterised by different patterns of muscular weakness (abdominals and gluteus maximus) and tightness (iliopsoas and spinal extensors) that connect the dorsal and ventral sides of the body [1]. In LCS there is overactivity and hence tightness of hip flexors and lumbar extensors, The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well. This imbalance results in an anterior tilt of the pelvis, increased flexion of the hips, and a compensatory hyper lordosis in the lumbar spine[2] .

The most common cause of LCS is a sedentary lifestyle. Sitting for prolonged periods can cause an imbalance between the muscles to develop. Due to prolonged sitting postures like sitting at a desk in school all day, the hip flexors become shortened or tight. This results in inhibition of gluteal activity. The lumbar lordosis increases due to the tight hip flexors [3] Ergonomics during work and ADL have a noted effect on onset development for LCS in people of all demographics. Multiple studies on Males, Females and Children present a prevalence of LCS, with 21% of school children between the ages 11-15 [4] developing the condition due to prolonged seating, thus shortening the hip flexors and weakening the abdominal muscles that are used to maintain correct posture [5]. Another study by study by Kale et al. in 2020[6] investigated the effects of these exercises on school children aged 11-15 who were diagnosed with Lower Crossed Syndrome by a certified practitioner. The students attended five weekly exercise sessions over two weeks. The exercises focused on specific muscles, stretching the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and erector spinae while strengthening the abdominal and gluteal muscles. Before and after the exercise interventions, the students were tested for hip flexor tightness and abdominal and gluteal muscle strength. The results showed a notable increase in the strength of abdominal and gluteal muscles, a reduction in muscle tension and increased muscle length. These findings support the effectiveness of stretching and strengthening exercises for treating LCS. However, the study was conducted on schoolchildren with a small sample size and a small intervention period, which limits the study to that specific population and represents the application of a short-term intervention.

Another study was conducted on female office workers, with similar findings, however the study presented patients with varying types of LCS (type A and B in the study, having varied negative effects on their craniovertebral angles and sagittal shoulder angles, which should be considered during assessment (as not to constrict observations to the lumbar region) [7]. Mechanical lower back ache presented corrected seated posture that would assist in male patients who present with LCS symptoms and work office jobs/seated jobs for prolonged periods of time, along with the common postures that lead to LCS and LBP [8].

Lower crossed syndrome can cause poor posture (aka postural dysfunction). This is because there is an imperfect relationship among various skeletal structures of the body, which may produce strain on the body’s supporting framework [9]. With faulty posture, the body is balanced less efficiently over its base of support. Therefore, any restriction, imbalance or misalignment of the musculoskeletal structures will have an adverse effect on the efficiency of movement [10]. One of the most common effects of bad posture is chronic back pain, usually because of disc degeneration, or simply from the excess pressure being endured by the spine. Disc degeneration happens when the discs between the vertebrates thin out and lose their cushioning. Moreover, as the spine and other bones change their position due to the long-term consequence of poor posture, the skeletal system begins to disrupt surrounding nerves. These pinched nerves can cause neurological issues, including shooting pain in the neck and other parts of the body. In the treatment of faulty posture five factors have to be considered: improvement of agility, improvement of mobility, re-acquisition of the ability to relax muscles, improvement in the strength of weak or relatively weak muscles and finally re-education of the postural reflex (the Bruegger’s exercise can be used for this) [11].

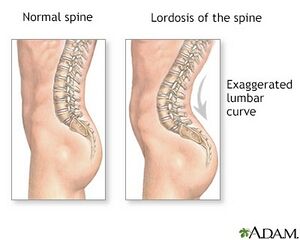

Another potential cause is overtraining certain parts of the body while undertraining others. For instance, if a person strengthens their hip flexors and back without focusing on their glutes and abdominals, this could lead to an imbalance. LCS can lead to excessive lumbar lordosis (swayback posture), contributing to low back pain and SI joint dysfunction. Gluteus muscles are inhibited with SI joint dysfunction with spasm of iliacus, piriformis, and QL (Pelvic shift) [12]. Specific postural changes such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external rotation of hip and knee hyperextension can occur. It also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: increased thoracic kyphosis and increased cervical lordosis [13].

LCS can also disrupt normal movement patterns of the lumbar spine and pelvis, leading to compensatory movements and increased stress on certain structures. Weakness in the gluteus maximus and abdominal muscles, which play key roles in stabilising the lumbar spine and pelvis, can result in increased load and strain on the lumbar spine during activities such as lifting, bending, and twisting. Over time, this increased load can contribute to degenerative changes in the lumbar spine, such as disc degeneration and facet joint arthritis, leading to chronic lower back pain (CLBP). Research suggests a strong association between LCS and its onset to Chronic Lower Back Pain (CLBP), emphasising the importance of accurate diagnosis and targeted intervention strategies. Addressing muscle tightness and weakness through targeted stretching, strengthening and postural re-education to help restore musculoskeletal balance and alleviate LBP[14].

Spinal Pathologies caused by LCS[edit | edit source]

Disc Herniation

Lumbar disc herniation is the rupture of the fibrous annulus (outer portion) of the intervertebral disc which progresses on to herniating the nucleus pulposus, the soft gel-like central portion of the disc that acts as a shock absorber providing stability in the spine [15]. The protrusion of the nucleus pulposus out of the disc leads to the compression of the spinal nerve and Cauda Equina resulting in an inflammatory response of the affected area [16]. Lumbar disc herniations are most commonly caused by trauma and aging [17]. An athlete with lower crossed syndrome who is a weight lifter with lower crossed syndrome will have a higher risk of a herniated disc. The sudden movement of lifting weight applied to that of an individual with muscle imbalance and lordosis which causes compression at the lumbar spine and discs will result in a higher risk of the disc to be damaged and cause herniation. This in relation to Lower Crossed Syndrome, the muscle imbalance contributes to stress on the spine and intervertebral discs . Tight hip flexor muscles and weak abdominal muscles lead to excessive lumbar lordosis. The curvature at the lower back and its function of load-bearing leads to increasing pressure on the lumbar disc [18]. The application of exercise for lower crossed syndrome can help to reduce stress of the discs at the lumbar spine especially.

Sciatica

Ropper and Zafonte (2015)[19] define Pain that radiates from the buttock downward along the course of the sciatic nerve. It mentions that the term "sciatica" has been used for a variety of back and leg symptoms, but the principal source is compression of a lumbar nerve root by disruption via soft tissue. Freiberg and Vinke (1934)[20] discuss sciatica as a symptom of pain that is attributed to a lesion of the lumbosacral part of the skeleton.

According to the same paper by Ropper and Zafonte (2015) [21]the symptoms of sciatica are as followed, pain that radiates from the buttock downward along the sciatic nerve. The pain may present as sharp pains or aching pains and these pains can radiate down the wither the middle or the lower buttock. This pain then may radiate across the thigh in cases in which the L5 nerve root is compressed and down the posterior aspect when the S1 is compressed. In most cases sciatica presents unilaterally. In cases where disk herniation, spondylolisthesis and lumbar stenosis are present and have occurred, lower back pain accompanies sciatica but is not a constant feature. Its very common for the upper sacroiliac joint to present with aching in the area surrounding the L5-S1.

A study by Falconer McGeorge and Begg (1948) [22]states that the mechanical causes of sciatica, involves a compression or disruption of the normal nervous system, specifically the sciatic nerve. When this occurs typically the nerve root undergoes a strain. There are different types of strains including angulating strains, which are the most commonly occurring kind, compressive and longitudinal strains. However, sciatica can happen via external factors such as piriformis syndrome in which the irritated piriformis muscle applies pressure onto the sciatic nerve causing a mechanical disruption. In a study by Sahu and Phansopkar (2021)[23], Lower-crossed syndrome is characterized by anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis and weak abdominal muscles as well as piriformis syndrome causing LBP. The anterior pelvic tilt caused by the characteristics of lower cross syndrome cause the hip saddle to sit more forward and the piriformis to then apply pressure on the nerve root. By addressing the root causes of LCS and prevent we can prevent the anterior pelvic tilt that cause piriformis syndrome. These include addressing the tight erector spinae, tight iliopsoas, inhibited gluteal and abdominals to ease compression off the sciatic nerve.

Risk factors for the development according to the paper by Parreira et al. (2018) [24]include poor general health such as sleeping and dieting, psychological stress and physical stress, prolonged sitting or walking were also discussed as contributing factors, sleep health in terms of positioning and quality. Exposure to physical stress were also mentioned as possible factors.

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is a degenerative condition of the spine, where facet joints can become displaced through degeneration of the vertebral discs [25]. This is a result of the ageing process, and the condition is common in adults where the discs have worn down and dried out. It can cause pinching of the various nerves that run down the spine and lead to tingling, pain or numbness down the leg. Lower cross syndrome is a relevant catalyst for this condition. The onset of increased lumbar lordosis through tight extensor muscles and hip flexors, can have a compressing effect on the already worn discs, while the weakened abdominal muscles offer little support to the stabilisation of the spine. This decreases the trunks integrity and allows for the facet movement to compromise the nervous system. By treating LCS, the patient will experience increased longevity of the vertebral column and slow down the onset of spondylolisthesis to improve quality of life and reduce onset of lower back pain.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Problem List

To aid an assessment, a clinician must obtain a comprehensive history focusing on the onset duration and characteristics of the patient's back pain. This can also assist in diagnosing chronic lower back pain (CLBP) where the pain persists for longer than 7-12 weeks [26]. Be sure to enquire about pain relief and aggravation factors in relation to the patients back pain, as well as any associated symptoms such as radiating pain or numbness. These fall into Red Flags in Spinal Conditions where a clinician would rule out spinal infection, Cauda equina, fracture and other malignancies. Explore the patients occupational lifestyle and activity related factors that may contribute to LCS and LBP such as All day living (ADL) activity and work related posture. Additionally, observe for avoidance factors due to Kinesiophobia, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and other Yellow flag related treatment that will be indicative of the patient’s condition and management procedure. These should be considered when providing exercise prescriptions to cater to the patient's specific needs for an optimal rehabilitation plan.

Continue the observational assessment with relevant clinical measurements, such as:

Observed muscle imbalance and mal-alignment, including excessive lumbar lordosis anterior pelvic tilt and altered movement patterns. (Insert Images – Lumbar lordosis, Anterior pelvic tilt, excessive cranial tilt).

Gait analysis – analyse the patient's gait to identify any abnormal movement patterns or compensations that may contribute to LCS and LBP. Increased anterior pelvic tilt causes greater knee flexion at the heel strike and mid stance. Anything >20 degrees is considered abnormal knee flexion when walking, as seen in the sagittal view when examining gait [27]. (Insert Image – Abnormal Knee Flexion)

Functional Movement Assessments – Use functional movement tests such as the Functional Movement Screen (FMS), to assess movement quality and identify dysfunctions that may predispose the patient to LCS and LBP where possible. May not be applicable for elderly or disabled patients[28].

Objective Outcome Measures – Incorporate validated outcome measures, such as the Oswestry Disability Index and a specific Visual Analog Scale (VAS) to quantify the severity of LBP during active and passive movement and monitoring of treatment progress.

Physical Examination

With consent, begin the physical examination by palpating relevant areas for tenderness and asses for myofascial trigger points in muscles commonly affected by LCS such as the hip flexors, lumbar extensors and iliopsoas. This will aid in assessing the severity of the patient’s condition and highlights the areas in need of more treatment.

Perform a thorough musculoskeletal examination to assess postural capability, range of motion, and muscle strength, to indicate any weaknesses and contributing factors to LCS that may be inducing lower back pain in the patient. Some specific and relevant special tests include:

•Thomas Test – Assess hip flexor tightness.

•Modified Thomas test – Evaluate hip flexor and rectus femoris flexibility.

•Lumbar range of motion – Measure flexion, extension, lateral flexion and rotation to identify movement restrictions. (Insert image – Rotational movement of lumbar)

•Muscle strength testing – assess strength of lumbar extensors, abdominals, hip flexors and gluteal muscles to identify weakness patterns, with Prone extension holds, plank, hip flexion and bi/unilateral glute bridges respectively. Remember to progress and regress exercises dependant on the patient and their inherent ability. (Insert images – muscle strength testing images)

It can be noted, that lower cross syndrome and its link to lower back pain can be occurrent in asymptomatic individuals, a study on screening for asymptomatic individuals provided evidence that women had an increased prevalence of lower cross syndrome without the symptoms of back pain than men, with a substantial difference in spinal extensor length, abdominal strength, bilateral gluteus maximus strength and iliopsoas length, with females more likely to develop weakening of these muscles (Priyanka, S. and Phansopkar, P. 2021) Identification of these factors is important in prevention of potential LBP by treating the mal-alignment before onset of pain occurs.

Principals of Exercise Prescription[edit | edit source]

Janda's Approach identifies and addresses the body's muscular imbalances and dysfunctional movement patterns. In treating muscular imbalances, including lower crossed syndrome, treatments should be prescribed according to Janda's four points. Those include restoring muscle balance, addressing and correcting posture and biomechanical issues, improving muscular endurance to prevent compensatory movements from fatigue, and finally, increasing neuromuscular control and coordination. All these covered in the form of manual therapy, education and exercise. This Approach offers a precise and targeted treatment once patterns and symptoms of Lower Crossed syndrome are identified (Page and Frank, 2002). Expanding on muscle balance, the exercises should align with Janda’s theory, aiming to correct the specific muscles. In this case, it focuses on strengthening weak muscles (gluteus maximus and abdominals) and stretching tight muscles (hip flexors and lumbar extensors). Exercise prescription must be specific to the individual’s needs (Whilemore, 1974). For lower crossed syndrome, exercises must target affected muscles and address posture. Janda’s approach can improve risk and condition of spinal conditions such as disc herniations. Strengthening the abdominals and stretching tight hip flexors can help relieve disc pressure, encouraging the healing process.

A study by Rajalaxmi et al. (2020) investigated the efficacy of Janda's Approach and Bruegger's Exercise in Lower Cross Syndrome and how it impacts the quality of life. The experimental study took three months, with 30 participants separated into two groups. One receives Janda's Approach, and the other receives Bruegger's exercise. The data was measured using a Goniometer, Visual Analog Scale, and SF-12 Scale. The research findings highlight that both interventions decreased pain and increased range of motion, improving functional activity significantly from before applying interventions. However, the result shows that Janda's Approach has a better result and outcome than Bruegger's exercise.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Strengthening

A systematic review by Mehta and Sharma (2022) reviewing treatment strategies for concluded that strengthening exercise is an efficient treatment for lower cross syndrome.

Plank

Abdelraouf et al., 2016 defined poor trunk control during everyday activities as a proposed contributing factor to lower back pain. Individuals with LBP have also been shown to exhibit decreased whole-body stabilisation and lumbar position sense compared to asymptomatic individuals. Core stability interventions have been demonstrated to be effective in changing spinal muscle recruitment, therefore improving core stability and decreasing lower back pain (Abdelraouf and Abdel-Aziem, 2016). The plank is a great abdominal and core exercise that can fix lower cross syndrome. It works the rectus abdominis and the other core muscles, including the abs. This exercise can have positive effects in supporting the active capabilities of muscles located along the spine. To perform a plank, you should assume a position with the shoulders and elbows flexed at 90°; maintain a straight, strong line from head to toes with no lowering of the hips and keep the neck in a neutral position. You are also required to keep their elbows directly beneath their shoulders, while ensuring there is no rounding of the shoulders or elevation of scapula off the thorax. Finally, you should contract your core musculature and gluteal muscles slightly to remain stable, while maintaining normal breathing patterns (Byrne, et al. 2014). Beginners should hold the position for at least 20 seconds. As you get more comfortable, hold it for as long as you can without compromising your form.

Step Ups

Jeong et al. (2015) suggests that gluteal muscles are essential to rehabilitating lower back pain, a common byproduct of LCS, because they are crucial in the stabilisation of the lumbar pelvic area. The gluteus maximus muscle, when contracted, helps to create a locking mechanism that provides stability to the sacroiliac joint. This stability prevents excessive movement that otherwise would cause pressure on the joints and disks between the vertebral prominences, SIJ, ultimately leading to back pain. Having strength in the gluteal muscles would also benefit the lumbar segmental stability which would lead to pressure from the L5-S1 resulting in lower back pain.

Page and frank (2007) states that Janda’s approach states that once peripheral balance is restored muscle balance must be addressed, Janda’s emphasises that firing patterns of muscle are more crucial to rehabilitation than strength of muscles, the muscle must be able to contract quickly in contraction with other muscles. This opposes the use of isometric strengthening therefore a concentric approach was selected. Step ups are a unilateral exercise that involves placing a leg onto a raised surface such as a step, stool or bench. Then with the other leg push the rest of your body up through and up onto the step and bring your feet together. The lead legs knee should be bent at 90 degrees before stepping through and push through the heel of the foot to reach the top of the box. Then with the lead foot come back down off of the step and repeat. The exercise engages the core, glute max, gastrocnemius, soleus quads and adductor magnus. In order to progress the exercise, you can introduce weight in the form of dumbbells to increase force required by the engaged muscle. Place the dumbbell on the side that the lead leg is on. Other factors that can be adjusted are the height of the step, this can be done for regressing and progressing. To progress increase the height as there is a greater range of movement required to step through and the opposite effect for a regression, shortening the box would make the exercise easier. Another progression directly related to LCS s the addition or of proprioception training. Page and frank (2007) state that once muscular imbalance is addressed Janda appeals for the increase of proprioceptive input into CNS. Therefore, by having the patient close their eyes as a progression we can address this part of rehabilitation. A study systematic review by Neto et al. (2020) assessing gluteus maximus activation during common strength and hypertrophy exercise, they highlighted step up as the exercise that elicited very high levels of GMax activity. They used MVIC, maximum voluntary isometric strength, as a value to measure this and step ups ranked the highest with a MVIC value % if 125, the next highest being hip thrusts at 75%. Lee and Jo (2016) states that MVIC is a very high reliability objective measure to assess muscle strength, further validating the suggestion of Neto et al. (2020) using step us as an exercise for glute maximus strengthening.

Flexibility

As mentioned before lower cross syndrome presents a case of muscular tightness (iliopsoas and erector spinae) around the lower back region. Therefore, when prescribing stretching exercises, they should target iliopsoas and erector spinae muscles. A study by Khan et al in 2022 assessed the effect of stretching and in managing lower back pain. A randomised control trial consisting of two groups, one control group and one undertaking a stretching exercise programme over the course of 4 weeks, twice a week. Outcomes of the results were measured using a numeric pain rating scale, Oswestry disability index (lower back function) and inclinometer and goniometer (Muscle length). The study findings showed before and after stretching interventions, significant differences in muscle length of the iliopsoas, hamstring, rectus femoris and erector spinae. Stretching increased Range of movement as well as decreased pain and disability in patients with Lower Cross Syndrome. Other studies have demonstrated the relationship of Disc herniation to the range of movement, function, and muscle movement (Ozturk and Aylanc, 2020). Therefore stretching exercises that focus on the inhibited muscles in Lower Crossed Syndrome can improve Disc herniation symptoms.

Kneeling Hip Flexor stretch

The kneeling hip flexor stretch improves the mobility of the hip flexor muscles (iliacus, psoas major, rectus femoris, and sartorius). It involves kneeling on one knee while bringing the opposite foot forward into a lunge position and then gently leaning forward to stretch the muscles at the front of the hip. The stretch is held for 15-30 seconds and repeated 2 to 4 times (Wilkins, 2006). To progress to a deeper stretch, increase the depth of the lunge by stepping further out with the leading foot and lowering the hips towards the ground. Or alternatively, hold onto the ankle of the leg that is behind you to lengthen the stretch through the distal muscle tendons. An elevated surface, such as a step at the front foot, can also increase stretch intensity. To reduce the difficulty of the exercise, shortening the distance between the knee and the leading foot can reduce the intensity of the stretch. The stability of the stretch can be increased by performing it beside a wall or chair to provide support for balance. Finally, to modify the exercise for those with knee pain symptoms, the stretch can be adjusted from kneeling to a standing hip flexor stretch instead.

In a study by Soholt in 2019, results of a modified single-leg squat and a half kneeling hip flexor stretch applied to a runner with lower crossed syndrome for six weeks showed a decrease in anterior pelvic tilt angle, an increase in strength at the gluteus Medius and gluteus maximus, and improved movement quality. Findings show that the two combinations of exercises can effectively improve movement quality and signs of lower crossed syndrome in runners. A further study of a wider population would be suggested in the future. Tight hip flexors, especially iliopsoas muscles, can lead to increased lumbar lordosis (Jorgenson,1993) and also an increase in pelvic tilt. This curvature is factored into causing more significant pressure on the lumbar discs, further contributing to lumbar spine disc herniation and discomfort (Chun et al., 2017). Therefore, the benefits of kneeling hip flexor stretch targeting the iliopsoas muscles and other hip flexor muscles can help to relieve compression and tightness in the lower back, which may help to mitigate the symptoms associated with Disc herniation. This can also be targeted towards Non-specific Lower Back pain especially with its relation to hip flexors tightness (Hatefi et al, 2021).

Lumbar METs

Muscle Energy Technique is a form of therapy that consists of muscle isotonic and isometric contraction followed by a gentle stretch engaging specific muscles that help to promote muscle lengthening and improvement of range of movement. As mentioned earlier in the study by Khan et al., MET is seen in other studies to be more effective than static stretching for treating shortened muscles (Magnusson et al., 1996). Khan et al. found that MET is more effective than a static lumbar stretch (not to discredit the efficacy of static stretching), with signs of more excellent range of movement, reduced pain, and improved function for people with lower crossed syndrome. In a systematic review, MET is also examined by (Franke et al., 2015) as an effective treatment for non-specific back pain. This shows that the application of MET can improve lower crossed syndrome and function, pain and range of movement with Non-specific lower back pain.

To apply MET in patients with Lower Crossed syndrome, the psoas major muscles and erector spinae muscles will be targeted as these are the muscles shortened to characterise Lower Crossed syndrome. It is performed with a therapist to support the patient in the seated pike position. Pressure is applied at the upper thoracic region of the back for greater leverage in performing the stretch, while the patient sits on a stable surface with their legs fully extended (see image). The patient should resist the pressure applied by the therapist for 5-7 seconds, beginning at 20% of their strength and gradually increasing this as the METs continue (Chaitow, 2013) repeating as the length of the muscle gradually increases.

Limitations to this intervention occur when a patient as no access to a therapist to conduct the METS, in this case the patient should ask a family or friend to assist them with the guidance displayed on this page. Should the patient for any reason have no access to external pressure, they may conduct the lumbar extensor stretch simply by reaching as far down their extended legs with their hands as possible and hold the stretch for 15-30 seconds and repeated 2 to 4 times (Wilkins, 2006).

Mobility - Bruegger’s Exercise

Also known as the “relief position,” focuses on reversing the tendencies of a slumping or slouched posture. The exercise is named after its developer, Alois Brugger, a Swiss neurologist of the 20th century, whose work focuses on repetitive strain injuries. To assume the relief position, sit at the very edge of your chair, without relying on the seat back for support. Hold your head high in the air, with a slight arch in the neck. Open your legs outward until your feet rest slightly to your sides, each foot facing outward slightly. Gently arch your back so that your belly can fully relax and your weight shifts onto your feet and your legs. Your pelvis should tilt forward and your breastbone should tilt up, toward the ceiling. Let your arms relax and turn them outward, with your palms facing up (Afzel, et al. 2022). This postural exercise should be done for 10 seconds every 20 minutes while seated. It can be incorporated into sit to standing, walking, and lifting. Over time you should experience the sensation of sitting and standing straighter and more naturally. When this occurs, improved posture will become more automatic and second nature. In a study exploring the effect of Bruegger’s exercise and spinal manipulation on chronic low back pain in association with lower crossed syndrome, results showed that Bruegger’s exercise, spinal manipulation and the combination of Bruegger’s exercise and spinal manipulation are effective treatment protocols

Additional Intervention[edit | edit source]

Addressing lower cross syndrome involves an approach that focuses on restoring muscle balance, improved joint mobility and enhancement of core strength and stability. While traditional physical therapy techniques such as stretching and strengthening exercises are essential components of recovery, additional research-based interventions such as Yoga, Pilates and group exercise sessions can offer unique benefits in managing LCS and alleviating lower back pain.

Yoga

Yoga is a mind-body practice that combines physical postures, breathing techniques and meditation to promote overall health and well-being. In the context of LCS, yoga can be particularly beneficial due to its emphasis on flexibility, strength and postural awareness. A systematic review presented evidence of long term improvement on lower back pain across randomised control trials involving 967 patients with CLBP and stronger evidence of pain management in acute cases of intervention in CLBP patients (Cramer, H. 2013). Certain yoga poses, such as Cat-Cow, Bridge pose, and Childs Pose, target the muscles involved in LCS, helping to release tightness in the hip flexors and lumbar extensors while strengthening the abdominal muscles and promoting proper pelvic-spinal alignment and reducing potential for disc compression due to muscle tightness. Additionally, the focus on breath awareness and relaxation techniques in yoga can help to reduce stress and tension, which are often associated with chronic lower back pain, the relaxational effects of yoga can reduce these psychological factors that contribute to LBP (Smith, C. 2007). (Insert images – Cat-Cow, Bridge Pose, Childs Pose)

Pilates

Pilates is A system of exercises developed by Joseph Pilates, emphasising core strength, flexibility and body awareness (Muscolino, J. 2004). Pilates exercises typically involve controlled movements performed on a mat or specialised equipment, such as the reformer or Cadillac. In the context of LCS, Pilates can be effective in targeting the deep stabilising muscles of the core, including the transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles (Lee, K. 2021), which play a crucial role in maintaining pelvic and spinal alignment. By strengthening these muscles and improving body awareness, Pilates can help correct postural imbalances associated with LCS and alleviate lower back pain. Rahimi et al. studied in 2022 the effects of Pilates exercises on the function of the Upper and Lower Extremities of middle-aged women with lower cross syndrome for 6 weeks. The program was conducted 3 times a week for 30 minutes. The outcome measures were evaluated using the Davies, side, and square hop tests. The use of Pilates showed signs of improved performance in the outcome measures and comparison to the control group. The study further found that the increase in abdominal muscle strength further proved the improvement in women with Lower Cross Syndrome. However, the study had its limitations, including the age and gender of the participants, the exclusion of injured people, and others that were uncontrollable, such as the participants' nutritional status and the subjects' psychological conditions (interest and motivation). A similar study should be conducted on elderly patients to assess the interventions applicability with people in a reduced ability demographic.

Group Exercise Sessions

Group exercise sessions, such as fitness classes or group training programs, offer a supportive and motivating environment for individuals with LCS to engage in structured physical activity. These sessions often incorporate a variety of exercises targeting different muscle groups, including cardiovascular, strength and flexibility exercises. ESCAPE-Pain (Hurley, M. and Thompson, F., 2024), a community based rehabilitation programme catering to the elderly, suffering from chronic and arthritic knee/hip pain provided economic and social value to the demographic, encouraging involvement in rehabilitation while improving mental health and objective physical function (p < 0.0001). The intervention helped the average individual save >£300 which would have been spent on national/private healthcare. When conducted by a professional, the study had high participant retention rates and positive outcomes in treating arthritic pain. Rheumatoid based arthritic pain is also prevalent in over 2 million patients in the USA (Vu-Nguyen et al., 2004). This inflammatory condition of the spine could be positively affected by a LCS focussed group exercise session, mimicking the model and conditions of ESCAPE-Pain to support patients suffering from lower back pain by preventing and treating the onset of inflammatory responses caused by rheumatoid arthritis by promoting a healthier lifestyle and improved immune function through exercise. Participating in group exercise sessions not only provides a well rounded workout but also encourages social interaction and accountability, which can enhance adherence to an exercise program. Instructors can modify exercises to accommodate individuals with LCS and provide guidance on proper technique and form to prevent injury and maximise benefits.

Further Education[edit | edit source]

It is important to educate patients predisposed to increased risk of attaining LCS to prevent its occurrence. If lower crossed syndrome remains untreated, it can result in obesity and low back pain in future. Sedentary behaviour may contribute to anxiety and depression and has been shown to be a risk factor for certain cardiovascular diseases. It is also linked to high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol levels. Sitting too much can also cause a decrease in skeletal muscle mass (Kale, et al. 2020)

Biomechanic expert, Stuart McGill, wrote a paper on the biomechanical implications of current practice in ADL and the clinic causing typical lower back pain. While he touches on the acute cases of trauma or high force activity that causes tissue damage, he emphasises on repeated sub-failure loads that lead to tissue fatigue and failure on the Nth repetition of load (or box lift, as an ADL example, prevalent in the ordinary patient) (McGill, S., 1997). The induction of stress over a repeated sustained period with spinal flexion in action, increases a sustained load can cause progressive reduction in the margins for safety. Prolonged stooped posture, much like that of the common office worker loads the posterior ligaments of the spine, encouraging the gradual tissue failure, leading to increased risk for disc herniation and all forms of spinal tissue injury (LBP). Recommendations for postural improvement and biomechanical correction are encouraged to promote more muscular involvement in ADL to protect the spine from compromission.

Reference List[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Sahu, P. and Phansopkar, P. (2021) Screening for lower cross syndrome in asymptomatic individuals. J Med Pharm Allied Sci, 10(6), 3894-3898.

- ↑ Physiopedia contributors. (2022) Lower Crossed Syndrome. Physiopedia, [online]. Available at https://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php?title=Lower_Crossed_Syndrome&oldid=323323 [Accessed: 18 March, 2024].

- ↑ Dhanani, S., & Shah, D. T. (2014). A survey on prevalence of lower crossed syndrome in young females. IJPSH, 1, 2249-5738

- ↑ Kale, S. S., Gijare, S. (2019) prevalence of lower crossed syndrome in school going children of age 11-15 years. IJPOT, 13(2): 176-179

- ↑ Rakholiya, P. A., Makwana, P. P., and Kakkad, A. (2019) To Compare the Activity of Scapular Upward Rotators during Isometric Shoulder Flexion with Forward Vs Neutral Head Posture in Normal Healthy Individuals. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther-An Int J, 13(2), 126.

- ↑ Kale, S.S., Jadhav, A., Yadav, T. and Bathia, K. (2020) Effect of stretching and strengthening exercises (Janda’s Approach) in school going children with lower crossed syndrome. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 11(5), 466-471.

- ↑ Puagprakong, P., Kanjanasilanont, A., Sornkaew, K. and Brady, W. S. (2022) The Effects of Lower Crossed Syndrome on Upper Body Posture during Sitting in Female Office Workers. Muscles, Ligaments & Tendons Journal, 12(4).

- ↑ Paikera, M., Barve, L. and Dubey, S. (2018) Mechanical Low Backache. International Journal of Trend In Scientific Research and Development, 2(6), 2456-6470.

- ↑ Isherwood, L., Britnell, N., Candido, G., and Watson, L. (2005) Postural health in women: the role of physiotherapy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can, 27(5), 493-500.

- ↑ Fowler, K., and Kravitz, L. (2011) The perils of poor posture. Idea Fitness Journal, 8(4).

- ↑ Burt, H. A. (1950). Effects of Faulty Posture. President's Address

- ↑ Sharma, V., & Kaur, J. (2017). Effect of core strengthening with pelvic proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on trunk, balance, gait, and function in chronic stroke. Journal of exercise rehabilitation, 13(2), 200.

- ↑ Ishida, H., Hirose, R. and Watanabe, S. (2012) Comparison of changes in the contraction of the lateral abdominal muscles between the abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre and breath held at the maximum expiratory level. Manual therapy, 17(5), 427-431.

- ↑ Nourbakhsh,M., Arabloo, A. M. and Salavati, M. (2006) The Relationship Between Pelvic Cross Syndrome and Chronic Low Back Pain. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 4(19), 119-128.

- ↑ Nedresky, D., Reddy, V. and Singh, G. (2023) Anatomy, Back, Nucleus Pulposus. StatPearls.

- ↑ Yu, P., Mao, F., Chen, J., Ma, X., Dai, Y., Liu, G. and Liu, J. (2022) Characteristics and mechanisms of resorption in lumbar disc herniation. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 24(1), 205.

- ↑ Nedresky, D., Reddy, V. and Singh, G. (2023) Anatomy, Back, Nucleus Pulposus. StatPearls.

- ↑ Gao, K., Zhang, J., Lai, J., Liu, W., Lyu, H., W., Lin, Z. and Cao, Y. (2019) Correlation between cervical lordosis and cervical disc herniation in young patients with neck pain. Medicine, 98(31).

- ↑ Ropper, A. H., & Zafonte, R. D. (2015). Sciatica. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(13), 1240-1248.

- ↑ Freiberg, A. H. and Vinke, T. H. (1934) Sciatica and the sacro-iliac joint. JBJS, 16(1), 126-136.

- ↑ Ropper, A. H., & Zafonte, R. D. (2015). Sciatica. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(13), 1240-1248.

- ↑ Falconer, M. A., McGeorge, M. and Begg, A. C. (1948) Observations on the cause and mechanism of symptom-production in sciatica and low-back pain. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 11(1), 13.

- ↑ Sahu, P. and Phansopkar, P. (2021) Screening for lower cross syndrome in asymptomatic individuals. J Med Pharm Allied Sci, 10(6), 3894-3898

- ↑ Parreira, P., Maher, C. G., Steffens, D., Hancock, M. J. and Ferreira, M. L. (2018) Risk factors for low back pain and sciatica: an umbrella review. The spine journal, 18(9), 1715-1721.

- ↑ Newman, P. H., & Stone, K. H. (1963). The etiology of spondylolisthesis. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery British Volume, 45(1), 39-59.

- ↑ Andersson, G. B. (1999) Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. The lancet, 354(9178), 581-585.

- ↑ Mock, M. and Sweeting, K. (2007) Gait and posture - assessment in general practice. Australian Family Physician, 36(6), 398–401, 404–405.

- ↑ Marquez, V. B., Medeiros, T. M., de Souza Stigger, F., Nakamura, F. Y. and Baroni, B. M. (2017) The Functional Movement Screen in elite young soccer players between 14 and 20 years: Composite score, individual-test scores and asymmetries. International journal of sports physical therapy, 12(6), 977.