Injury Prevention in Sport

Original Editor - Wanda van Niekerk

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Physical activity and sports participation is encouraged by all health care professionals as it has numerous positive effects on a person's health. There is however, the significant burden of sport-related musculoskeletal injury, with the greatest risk being in the youth and young adult populations.[1] It is vital to incorporate primary injury prevention and make this a public health priority as this will have significant implications for reducing long-term consequences of musculoskeletal injuries, such as early post-traumatic osteoarthritis.[1]

The Importance of Sport Injury Prevention[edit | edit source]

One of the building blocks of a healthy lifestyle across the lifespan is physical activity and participation in sport and recreation is encouraged by all health care professionals. The sport-related injury burden is however significant and there is a need for research into the evaluation of injury prevention strategies in all sports across all ages.[2] The youth and young adult populations have the highest participation rates, but also the highest injury rates and sport is the leading cause of injury in youth.[3][4] Studies have shown that 20% of schoolchildren will miss at least one day of school per year due to sports injuries, and one in three youth seek medical attention for sports-related injuries per year. Even adults lose at least one day a year from work as a result of sport-related injury.[2][5] Sport is the the leading cause of all injuries in youth, but also has an impact on the adult population. Furthermore, the financial implications of sport-related injuries are huge. In Australia alone the direct cost of sport-related injury over a seven year period amounted to an estimated 265 million Australian dollars.[6] From these injury rates and high financial costs, it is clear that the injury-burden is significant and that there is a need to implement evidence-based injury prevention strategies to reduce the risk of injury in youth, and also across the lifespan. Lower extremity injuries are the highest overall burden of sport-related injury at 60%, of which 60% of these are ankle and knee joint injuries.[1]

Injuries in sport may also contribute to the rising burden of overweight and obesity in youth, with 8% of youth dropping out of sport per year because of injury or fear of injury.[7][8] This leads to a further decline in physical activity participation and this has negative implications (obesity, post-traumatic osteoarthritis) on future health. Reducing the significant burden of sport-related injury would have great impact on quality of life through the promotion of physical activity.[1]

Physical activity, sport and recreation is vital in youth and for all age groups to have a healthy lifestyle, to promote healthy growth and development, to prevent chronic disease and to reduce stress.These benefits from participation in sport and recreation has important implications for public health, but the injury risk must be balanced and addressed.[1]

Injury Prevention - A Systematic Approach[edit | edit source]

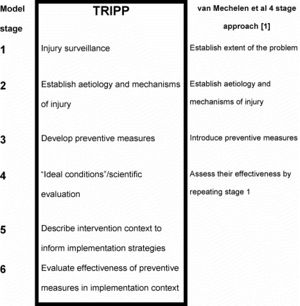

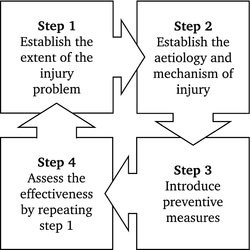

Van Mechelen (1992) proposed and developed the four-step model for injury prevention in sports and this model has been the foundation for the development and evaluation of injury prevention programs since it inception.[10] The model includes the following steps that may be followed in the prevention of sports injuries:

- Establishing the extent of injury in a specific population through surveillance systems

- Identifying the risk factors for injury in a specific population

- Development and validation of injury prevention strategies

- Evaluation of these injury prevention strategies by measuring the impact of the prevention strategy on the incidence of injuries using appropriate surveillance systems

Various study designs are used to investigate the effectiveness of injury prevention strategies, and although randomised controlled trials are the golden standard, it is not always possible or ethical, therefore less rigorous study designs such as quasi-experimental, cohort and case-control studies are also used. As a result there are usually inherent methodological limitations that do introduce bias and thus limits the interpretation of study findings to some extent.[11][12]

Emery and Pasanen (2019) states that: "The "best" injury prevention program is the one that can and will be adopted and sustained by athletes, coaches, and sporting bodies."[1] Injury prevention research has gained ground and is being used in real world settings. The challenge being to implement cost effective injury prevention strategies in real life circumstances.[13] One of the projects that addresses this challenge is the Translating Research into the Injury Prevention Practice (TRIPP) Framework.[14] The TRIPP framework is an extension of the Van Mechelen model and includes two additional steps that are necessary for the translation of the effectiveness of injury prevention strategies into real life practice.[14] The two additional steps include the understanding of the real world for which the specific intervention is being developed and the evaluation of this intervention in a real-world setting. Factors that should be considered when determining if an injury prevention program will be feasible in the real world may include:[14]

- the sport participants' age group

- the level of play

- type of sport

- organisational structure in which original intervention was evaluated.

Another framework that has received increased attention in the context of sports injury prevention strategies is the Reach Efficiency Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework. It was originally developed to investigate the impact of health promotion interventions. It describes five steps to translate research into action:[15]

- reach the target population

- effectiveness or efficacy

- adoption by target audience

- implementation consistency and costs and adaptations made during delivery

- maintenance of intervention effects in individuals and over time

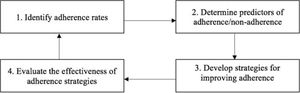

Multiple factors influence the adherence to an the implementation strategy that will maximise the effectiveness of a specific sport injury prevention program. It is necessary to create a good balance between evidence and real world implementation throughout the development and evaluation of the intervention, to alleviate problems of poor adherence.[1] Owoeye et al (2018) described the four key steps towards a more rigorous approach that may promote adherence to interventions.[16]

Sport Injury Prevention Programs[edit | edit source]

Sport injury prevention programs can reduce the number of injuries as well as the severity and extent of injuries.[18] The three areas where injury prevention in sport is focused on is:

- training strategies

- modification of sport rules and changes in policies

- equipment recommendations

Training strategies focus on modifiable intrinsic (athlete related) risk factors such as strength, endurance and balance through neuromuscular exercise interventions. Extrinsic (environmental) risk factors are targeted through rule modification and equipment strategies (e.g. body checking in youth ice hockey, ankle braces, cricketers wearing British Standard compliant helmets when batting, wicket keeping or fielding close to the batter.)

Neuromuscular training injury prevention programs[edit | edit source]

Prospective studies often investigate neuromuscular training injury prevention programs in team sports with attention toward amateur and elite athletes (adult and youth). These programs are often led by the coach or trainer, after a comprehensive training workshop by a physiotherapist or strength and conditioning coach with the relevant expertise.[1]

Neuromuscular injury prevention programs do reduce the risk of injury as seen in various studies.[18][19] In youth sports such as soccer, European handball and basketball, a 37% reduction in lower limb injury risk was reported.[20] Other studies investigating the protective effect of exercise interventions as methods to reduce the risk of injury, showed 37% reduction in overall injury risk and a 47% reduction in overuse injury risk. An even greater preventative effect is reported when neuromuscular injury prevention programs concentrated on proprioception, balance and strength.[21] No preventative effect is seen with intervention programs focused on stretching.

Neuromuscular injury prevention programs consist of exercises aimed to:[20]

- improve balance

- improve strength

- improve agility (coordination, cutting and landing techniques)

These programs are usually introduced as part of an extended warm-up program and include several neuromuscular training components such as:

- aerobic components

- balance

- strength

- agility

Levels of progression are included and participants progress as they see fit. These programs need to be feasible and fit in a real world sporting context (e.g. as part of the warm-up routine and with no added equipment required).

There is evidence that these types of injury prevention programs are successful in reducing injury risk in elite, adolescent and pediatric athletes. These findings have also been translated to more generalised populations with good effect. More research is needed to gain a further understanding of the adherence to and the maintenance of these types of programs.[1]

Examples of Neuromuscular Training Components[edit | edit source]

Aerobic Components[edit | edit source]

Agility Components[edit | edit source]

Strength Components[edit | edit source]

Balance Components[edit | edit source]

Sporting Rules and Policy Changes to Prevent Injuries[edit | edit source]

Rules and policies in sports are key in regulating the sport, but some of these rules and policies have been specifically developed and changed to reduce the risk of injury. Examples of evidence-informed policy and law changes are:

- Body checking in ice hockey: Disallowing body checking in all levels of play in 11- and 12 year old leagues, led to a 50% reduction in injury risk, and in older age groups in non-elite leagues led to a 54% reduction in injury risk.[28][29]

- World Rugby's Executive Committee has recently approved a package of law amendments to be trialed to prevent injury. One of the six laws to be further trialed includes the High Tackle Technique Warning. This law has been successfully trialed at the World Rugby U/20 Championship for the past two years and it showed a reduction of the incidence of concussion by 50%.[30]

- Cricketers are required to wear British Standard compliant helmets when batting, wicket keeping or fielding close to the batter.[31]

Further research is needed on the impact of rule and policy changes in sport to prevent injury.

Equipment Recommendations[edit | edit source]

The use of appropriate protective equipment may prevent musculoskeletal injury in sports. Such equipment may include taping, bracing and wrist guards.[1] Dizon et al investigated the protective effect of ankle taping and bracing in previously injured adults and youth athletes. The risk of an ankle sprain re-injury was reduced by 69% and 71% respectively.[32] However,taping or bracing is not a strategy for primary prevention in healthy populations with no previous history of ankle injury.

The use of wrist guards in snowboarding showed a significant protective effect in reducing the risk of wrist injuries, wrist fractures and wrist sprains.[33]

A combination of educational approaches (social media and legislation) may be a good way to promote the use of protective equipment where required.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Emery CA, Pasanen K. Current trends in sport injury prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Feb;33(1):3-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Conn JM, Annest JL, Gilchrist J. Sports and recreation related injury episodes in the US population. Inj Prev 2003;9:117-23.

- ↑ Emery CA, Tyreman H. Sport participation, sport injury, risk factors and sport safety practices in Calgary and area junior high Schools. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;14:439-44.

- ↑ Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH, McAllister JR. A survey of sport participation, sport injury and sport safety practices in adolescents. Clin J Sport Med 2006;16:20-26.

- ↑ Emery C. Risk factors for injury in child and adolescent sport: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:256e68

- ↑ Finch CF, Kemp JL, Clapperton AJ. The incidence and burden of hospital-treated sports related injury in people aged 15+ years in Victoria, Australia, 2004 - 2010: a future epidemic of osteoarthritis? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:1138e43.

- ↑ de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for schoolaged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:660-7.

- ↑ Grimmer KA, Jones D, Williams J. Prevalence of adolescent injury from recreational exercise: an Australian perspective. J Adolesc Health 2000;27:1-6.

- ↑ Von Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Med 1992;14:82-99.

- ↑ Von Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. A review of concepts. Sports Med 1992;14:82-99.

- ↑ Emery CA. In: Verhagen E, van Mechelen W, editors. Research designs for evaluation studies in research methods in sport medicine. Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 169 - 80.

- ↑ Page P. Research Designs in Sports Physical Therapy. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Oct; 7(5): 482–492.

- ↑ Timpka T, Ekstrand J, Svanström L. From sports injury prevention to safety promotion in sports. Sports Med 2006;36:733-45.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Finch C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:3-9.

- ↑ O'Brien J, Finch C. The implementation of injury prevention exercise programmes in team ball sport: a systematic review employing the RE-AIM framework. Sports Med 2014;44:1305-18.

- ↑ Owoeye OBA, McKay CD, Verhagen EALM, Emery CA. Advancing adherence research in sport injury prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Sep;52(17):1078-1079.

- ↑ Owoeye OBA, McKay CD, Verhagen EALM, Emery CA. Advancing adherence research in sport injury prevention. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Sep;52(17):1078-1079.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Emery CA, Roy TO, Whittaker JL, Nettel-Aguirre A, Mechelen W. Neuromuscular training injury prevention strategies in youth sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:865-70.

- ↑ Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:871-7.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hübscher M, Zech A, Pfeifer K, Hänsel F, Vogt L, Banzer W. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:413-21.

- ↑ Owoeye OBA, Palacios-Derflingher LM, Emery CA. Prevention of ankle sprain injuries in youth soccer and basketball: effectiveness of a neuromuscular training program and examining risk factors. Clin J Sport Med 2018;28:325-31.

- ↑ The Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia. Ready, Set, Prevent, Injury Prevention Program - The Warm-up - CHOP (1 of 4). Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xETe5_NnCWQ [last accessed 03 January 2020]

- ↑ Medstar Health.Agility Exercise for ACL: Lateral Shuffle. Published on 24 October 2013. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iBmvPEWt5og[last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ Medstar Health. Agility Exercise for ACL: Grapevine. Published on 24 October 2013. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWavy_f2sVY. [last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Ready, Set, Prevent, Injury Prevention Program - Strengthening, Phase One and Two - CHOP (3 of 4). Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Nee7qDSnVc&t=10s [last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Ready, Set, Prevent, Injury Prevention Program - The Plyometrics, Phase One and Two - CHOP (4 of 4) Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDm3zvPKcS0&t=18s[last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ Duke Health. Balance Training with Duke Sports Medicine. Published on 22 June 2010. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W8o_nOymwOU.[last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ Black AM, Hagel BE, Palacios-Derflingher L, Schneider KJ, Emery CA. The risk of injury associated with body checking among Pee Wee ice hockey players: an evaluation of hockey Canada's national body checking policy change. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1767-72.

- ↑ Emery CA, Palacios-Derflingher L, Eliason P, Black AM, Krolikowski M, Spencer N, et al. Evaluation of body checking policy in Bantam ice hockey players: a multivariable analysis. Clin J Sport Med 2018;28-48.

- ↑ SA Rugby. World Rugby approves law trials to further injury-prevention. Published on 2 August 2019. Available from https://www.sarugby.co.za/en/articles/2019/08/08/World-Rugby-approves-new-law-trials [last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ Sports Legal. The prevention of head injuries in cricket: will new regulations help? Published on 26 January 2017. Available from https://www.sports.legal/2017/01/the-prevention-of-head-injuries-in-cricket-will-new-regulations-help/. [last accessed 3 January 2020]

- ↑ Dizon JMR, Reyes JJB. A systematic review on the effectiveness of external ankle supports in the prevention of inversion ankle sprains among elite and recreational players. J Sci Med Sports Exerc 2010;13:309-17.

- ↑ Russell K, Hagel B, Francescutti LH. The effect of wrist guards on wrist and arm injuries among snowboarders: a systematic review. Clin J Sport Med 2011;17:145-50.