Huntington's Disease: Case Study

Original Editor - User:Max Handelman Top Contributors - Max Handelman, Matthew Petto, Brandon Macleod, Juno Kong, Wolf Dobrovetsky, Soren Hertz and Matthew Tadros

Abstract and Purpose[edit | edit source]

This case study was developed by Physiotherapy students (PT1) at Queen's University with the intention of increasing our knowledge of Huntington's Disease and neurological conditions as part of our PT858: Neuromotor Function II.

The purpose of this case study is to demonstrate an example of physiotherapy management for an individual in the early intermediate stage of Huntington’s Disease (HD), approximately 4 years post diagnosis. This case study illustrated a patient who presented with motor, emotional and cognitive impairments as a result of HD. Patient specific problems were noted and associated short and long term goals were developed to manage current symptoms as well as mitigate disease progression. Treatment for the patient included functional strengthening, aerobic endurance, and education. Referrals for other healthcare professionals such as clinical psychologist, occupational therapist, and speech language pathologist were noted in order to help manage the multi-faceted presentation of his disease beyond the scope of physical therapy. The study will help students gain a comprehensive understanding of typical clinical presentations, physiotherapy assessments, interventions, interdisciplinary management, and other relevant factors related to the disease.

Introduction to Huntington's Disease[edit | edit source]

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative disease that is progressive in nature. First described by George Huntington in 1872, HD typically has an adult onset with irreversible motor, affective, and cognitive symptoms over the duration of the disease. [1] The average age of diagnosis is 45, with the disease terminating in death after 17 years on average. [2] The current prevalence of HD in the Western hemisphere is 12 cases per 100,000 births; this may vary, as prevalence is as high as 700 cases per 100,000 births in Venezuela and significantly lower rates in Japan and Taiwan.[1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Huntington’s Disease is caused by a DNA error found in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene. It consists of a repeat of the CAG trinucleotide in the Huntington gene in the short arm of chromosome 4.[3][4][5] In HTT, there are typically 18 repeats of CAG while individuals with HD have 40 or more repeats.[1] Individuals with 40 or more repeats are guaranteed to develop HD symptoms and may even develop symptoms in childhood (Juvenile HD)[1]. Individuals with 36-39 CAG repeats have reduced penetrance and may develop symptoms later in life or not at all.[1]

Huntington’s Disease causes progressive degeneration of parts of the Basal Ganglia, specifically the caudate nucleus and the putamen.[4][6] Degeneration of this area can cause issues with coordinated movement, voluntary movement, and postural changes.[6]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

An individual diagnosed with HD typically presents with a triad of symptoms of chorea, dementia, and rigidity as the most common symptoms.[1]

In early stages of HD, individuals are still largely functional without any major deficits.[7] The most common deficits in early stages of manifested HD are diminished ability to perform rapid alternating movements, mild chorea, difficulty with voluntary movements, and abnormal eye movements.[7] Additionally, cognitive changes may be present such as issues with executive functioning and short-term memory.[7] Individuals with HD may experience difficulty planning their day, or may present with decreased processing speed.[6] Behavioral or psychiatric changes will often be prominent before any serious motor impairment develops [7]. The most common psychiatric symptom of HD is depression, however anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, suicidal tendencies and apathy have all been documented in the early stages.[6][1]

As the disease progresses towards middle stages, motor impairments may become more debilitating. Chorea becomes more limiting, causing issues with gait and activities of daily living (ADLs).[7] Another common motor feature often developed during the early to middle stages is dystonia, characterized by involuntary muscle contractions.[1] Peripheral symptoms that are common also include severe weight loss, osteoporosis, and atrophy of skeletal muscle due to the inability to control voluntary movement.[1] Cognitive declines in short-term memory and general processing speed will also be more apparent in this stage of HD.[1][7]

In the final stages of HD, the individual will require assistance in all aspects of living.[1][2][7] The individual is functionally incapacitated, and will have almost no voluntary movement.[7] Chorea may be severe, however it is often replaced with other symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity or dystonia.[2][7] Dysphagia, dysarthria, and incontinence are also characteristic seen in late-stage HD.[7][8] Psychiatric symptoms may become harder to diagnose due to the inability of the individual with HD to communicate.[1][2][7] The late stages of HD often involve preparing the individual for death, with their primary care being passed down to palliative care.[2]

Subjective Examination[edit | edit source]

Patient Profile and History of Present Illness (HPI)[edit | edit source]

Barry Johnson is a 38 year old male that has been diagnosed with Huntington’s Disease (HD). He was initially diagnosed 2 years ago following the onset of concerning symptoms including mood swings, social withdrawal, apathy, difficulty concentrating, memory lapses, general clumsiness. After meeting with his family doctor, Barry was referred to the neurologist which confirmed the diagnosis of HD. Mr. Johnson is currently in the early-intermediate stages of his disease, demonstrating difficulty with various motor activities including walking, trouble holding onto things, and other fine motor tasks. Barry is generally a happy person, but has been dealing with depressive episodes since the onset of his disease, as well as increased irritability and agitation. He also notes feeling a little more cloudy in his mind and forgetful of certain details regarding responsibilities at work and at home, which leads to him taking more time on what used to be simple tasks.

Past Medical History (PMHx)[edit | edit source]

N/a

Medications (Rx)[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson was prescribed 25 mg per day of Valium (Diazepam) by his doctor following the onset and increase in depressive symptoms as well as some initiation of chorea and dystonia. However, the combination of impaired gait, increasing chorea and emotional/cognitive dysfunction may indicate his medications need to be adjusted. [9]

Health Habits (HH)[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson does not smoke cigarettes or use recreational drugs. However, he does indulge in the occasional scotch or alcoholic drink on weekends.

Family History (FHx)[edit | edit source]

No previous family history of cancer, CVD, or any genetic disease.

Social History (SHx)[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson has been working in his family landscaping business for the last 10 years. While his job is largely focused on the management side of the business, he did engage in active gardening somewhat often to which he has been having more difficulty with as the disease has progressed. He currently employs other colleagues to do more of the hands-on work and has transitioned towards a more passive role in the head office. At home, Barry has been experiencing trouble with doing ADLs independently which includes: self cleansing, house chores, and navigating his 2 story home. He lives at home with his wife, Candice, and daughter, Anita in their two story home. He noted that he and his wife have been arguing more than they used to in their marriage. Aside from his semi-active landscaping job, Mr. Johnson used to be an avid soccer player, and regularly joined his friends on the weekends to play in a men's recreational league. While he is no longer playing, he tries to engage in some form of activity on 2 of his evenings during the week after work, which consists usually of walks outside without a gait aid with his daughter alongside. Additionally, Barry volunteered with the local minor soccer association as a house league coach 3 nights a week, but the progression of HD and functional and restrictions, alongside his increased self-consciousness of his condition, have reduced his ability to be involved all together.

Past Functional History (FnHx)[edit | edit source]

Prior to his diagnosis and onset of symptoms, Barry was a fully independent and active person. He was extremely active and hands-on in his work, doing chores in his home, as well participating in recreational activities on a weekly basis. He was fully independent in all ADLs and aspects of mobility. Up until initial consultation, Barry has not been using a gait aid to ambulate, however has experienced a number of trips and minor falls while at home and at work.

Current Functional Status (FnSt)[edit | edit source]

Barry has experienced a number of instances of instability in recent memory, including stumbling at work and at home. His motor function has been impaired as his chorea has become more pronounced at this stage of his disease progression, which has exacerbated his depression, making him feel more self conscious at work and in his personal life. Barry is not fully independent with mobility and ADLs at this point, and can not engage in his work and recreation as he used to. Barry definitely feels more fatigued with longer periods of activity than he used to.

Current Interventions[edit | edit source]

Barry is planning on attending physical therapy to manage his symptoms and improve his quality of life. He will also be attending counseling and support groups to help him cope with the emotional and psychological effects of the disease.

Goals[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson would like to sustain and or improve independence in his ADLs and balance during ambulation, as well as generally more as ease and comfort with the manifestation of the disease. Barry does not feel fully comfortable emotionally in social settings, and would like to learn to control his disease and learn compensatory strategies so that he can engage in social settings as much as possible.

Objective Examination[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

On observation, Mr Johnson appears to be sitting with an upright posture, consciously aware of the setting he is in. He does appear to have slight fidgets as if he is uncomfortable with the static sitting on the plinth. He has no noticeable atrophy of the the U/E and L/E

Muscle Strength Testing[edit | edit source]

MMTs for the U/E and L/E were tested in order to assess possibly strength deficits that might be resulting in Mr. Johnson’s impaired gripping ability as well as trouble with ambulation. Mr. Johnson displayed weakness/reduced grip strength bilaterally (3/5), as well as slightly decreased strength in the knee flexors and extensors (4/5). All other muscle groups were strong. These results allow for an intervention program to be designed to address specific deficits in strength as well as sustain others to prevent decline with disease progression.[10]

Balance[edit | edit source]

As addressed during intake, Barry deals with instability during ambulation. The Berg Balance Test was performed by the patient, as it has been shown to be valid and reliable in assessing this portion of deficit in people with HD. [11] Barry achieved a score of 32 on the test, indicating an increased risk for falls with HD.[12]

Gait[edit | edit source]

A general gait assessment was done with Mr. Johnson following his subjective examination. Gait was observed as the patient was walking into the consultation to try and see natural deficiencies, if any. Barry was most definitely unstable walking in and was not confident in walking through this new environment swiftly. As a result, the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test was performed, so that this motion again that was observed when getting up from the waiting room and coming to the plinth could be clinically documented. The TUG test has been well validated for improving physical functioning in people with manifest HD which is why it was used.[13] The test involved standing up from the chair, walking 3 m, turning around, and then returning to the chair. The test is done two times and the score is averaged. Barry completed the test in 14 secs, which indicated his risk for increased falls with HD.[12] In addition, the 10m walk test was performed to test the patients speed which seemed to be limited when entering the consultation. Patient had a 0.81 m/s speed, which was indicative of lower speeds for his age group and increased falls risk.[14]

Cognitive/Emotional/Mental State[edit | edit source]

Due to Mr. Johnson’s expression of some of the emotional and mental challenges that he experiences as a result of his disease, it was determined that it would be appropriate to use the SF-36 questionnaire to measure quality of life and level of participation. It was a quick form which was helpful to save time for other portions of the consultation, but had large validity and reliability for HD which is why it was used.[15] Barry scored a 47 on the test, indicating he is on the lower side of disability.

Hypertension[edit | edit source]

One comorbidity that was screened in Mr. Johnson was for the presence of hypertension. Hypertension has been shown to be a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor that plays a role in the disease severity and progression in HD. It has been shown that patients with hypertension have worse cognitive function, higher depression scores, and more advanced motor progression over time. It also appears as though taking antihypertensive medication has less motor, cognitive, and functional impairment compared to those patients with untreated hypertension.[16]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Berg Balance Scale[edit | edit source]

The Berg Balance Scale (BBS) is a 14-item list used to determine an individual’s level of balance through several different balance tasks. Each item is scored on a five-point scale of 0 to 4, with 0 being the lowest level of balance and 4 being the highest level (Max score of 56 overall). Items of the BBS involve tasks in sitting and standing for static, transitional, and challenging dynamic positions. In a study by Quinn et al. (2013), the BBS and several other outcome measures were tested for reliability and minimal detectable change (MDC) for evaluating physical functioning in individuals across all stages of HD. Test-retest reliability of the BBS was found to be suitable (>0.90) for individuals across manifested stages of HD.[13] Furthermore, the BBS had a low MDC indicating a sensitive test. From having both high test-retest reliability and a low MDC, it can be inferred that the BBS is a valid and reliable test for measuring physical function levels in individuals with HD. This outcome measure specifically targets the ICF category of Body Structure and Function (Impairments), and will help to inform on the patients balance deficits.

Huntington's Disease Activities of Daily Living (HD-ADL) Scale[edit | edit source]

The Huntington's Disease Activities of Daily Living (HD-ADL) scale is a 17-item informant-completed instrument for rating adaptive functioning in Huntington's disease (HD) patients. Principal components factor analysis of the HD-ADL revealed four factors (General Functioning, Domestic Activities, Home Upkeep, and Family Relationships). The HD-ADL scores correlate with Shoulson and Fahn's total functional capacity (TFC) index (r = -0.89). The HD-ADL scale is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing adaptive function in HD patients. This scale is utilized by the informant who is familiar with the patient's level of functioning. The tool allows the clinician to obtain an indication of the severity of the patient's functional disability, as well as monitor therapeutic interventions. This outcome measure specifically targets the ICF category of Activity (Limitations), and will help to inform on the patients ability to perform ADLs and self hygiene.[17]

Short Form 36 (SF-36) Scale[edit | edit source]

SF-36: This patient questionnaire measures quality of life and level of participation. The 36 questions are grouped into 8 sub-scales (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health).[18] The SF-36 tool is an excellent measure for assessing QoL and participation for those with HD because of the far reaching inventory looking at many of the facets of life that are affected by the disease. As well, it has a robust construct validity and test-retest reliability which makes it highly useful for monitoring effects of disease throughout its course.[15] From a realistic standpoint, the SF-36 is a brief and quick measure to administer and, therefore, easier for patients at various stages of HD to fill out. This outcome measure specifically targets the ICF category of Participation (Restrictions), and will help to inform on the patients health related quality of life.

Problem List and Associated Short (STG) and Long Term (LTG) Goals[edit | edit source]

Body Structure and Function:[edit | edit source]

Problem List[edit | edit source]

- Cognitive deficits

- Psychosocial issues

- Chorea

- Pain

- Balance deficits

- Fine motor deficits

Goals[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson demonstrated balance deficits during the assessment, which can explain his initial reporting of difficulties with walking as well as general clumsiness. This is not unexpected for a patient diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, as progressive worsening of balance is a common sign associated with this condition.[19] Mr. Johnson received a score of 32 on the BBS which indicates an increased risk of falls.[12]

STG #1: By 6 weeks, Mr. Johnson will demonstrate an increase on his BBS scores equivalent to the minimal detectable change (MDC = 5) for individuals with middle-stage Huntington’s disease.[13]

LTG #1: By 12 weeks, Mr. Johnson will achieve a score greater than 40 on the BBS which is above the threshold that identifies fall risk for individuals with Huntington’s disease.[20]

Activity Limitations[edit | edit source]

Problem List[edit | edit source]

- Walking/mobility deficits → chorea causing involuntary and jerky movements

- Difficulty eating and drinking

- Preparing and cooking food

- Using the bathroom (toileting)

- Speaking

- Dressing

Goals[edit | edit source]

One of Mr. Johnson’s most problematic tasks is independently toileting, which he has been struggling with as the disease progresses. Specifically with symptoms such as chorea, dystonia and fine motor deficits, Barry has required assistance with performing many activities of daily living. One of the aspects of independently toileting that Barry struggles with is moving from standing to sitting, and vice versa. While performing the sit to stand movement, lack of postural control produces difficulty in performing the task in individuals with HD.[21]

STG #1: By 6 weeks, Mr. Johnson will demonstrate an increased score of at least 2.3 seconds (MCID) on the Five Times Sit to Stand Test.[22]

LTG #1: By 12 weeks, Mr. Johnson will be able to conduct all of the movements necessary to independently perform toileting in his home environment, as measured by a score of at least 6 on the toileting portion of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM).

As Mr. Johnson has progressed from early to mid-stage HD, his postural balance and stability, as well as coordination has decreased. The main structural impairments like chorea and dystonia have also worsened. This has resulted in Mr. Johnson recently experiencing a couple of falls and the need for the prescription of a gait aid. Mr. Johnson has been presenting with reduced gait speed, step length, cadence, and difficulty with turning.[23] Provision of gait aids can be difficult with HD patients, due to chorea, fine motor issues, dystonia and attentional issues.[23] Due to these difficulties with ambulation, Mr. Johnson is being prescribed a 4-wheeled walker (4WW) to improve gait speed and reduce falls risk.[24]

STG #1: By 2 months, Mr. Johnson will demonstrate increased gait speed while ambulating with a 4WW using the 10 Metre Walk Test. The patient will achieve a gait speed of 1.27 m/s, which would be a MDC based on the initial recorded gait speed.[14]

STG #2: By 3 months, Mr. Johnson will be able to safely ambulate 300m using a 4WW within 6 minutes as measured by the 6 Minute Walk Test.

LTG #1: By 6 months, Mr. Johnson will be able to maintain the use of a 4WW with no reported falls and ability to ambulate safely within the community. Patient will report falls and perception of falls risk using the Fall Risk Assessment Tool.

3) Participation Restrictions:[edit | edit source]

Problem List[edit | edit source]

- Reduced ability to aid family in ADLs

- Symptoms of depression and anxiety due to decreased participation in daily activities resulting in social isolation/withdrawal

- Physical and psychosocial restrictions to volunteering

- Increasing caregiver burden on family as disease progresses

Goals[edit | edit source]

As Mr. Johnson is within the early-intermediate stage of HD, his functional deficits are not restricting him from completing his day-to-day tasks with his family’s landscaping company, and have restricted his limits to completing hands-on work. Additionally, he has begun to have issues with ADLs, resulting in anxiety/depression and overall withdrawal from ADLs in general. One of the participation restrictions that weighs on him most heavily would be his self-implicated reduction in volunteering with his local soccer association as a coach for minor soccer league teams, as he feels his physical symptoms and increased self-consciousness of presentation of HD will hinder his ability to be involved with coaching at all

STG #3: Within 12 weeks, improve SF-36 score by the 5 points overall through implementation of group aerobic, anaerobic and gaiting training[25]

LTG #3: Within 6 months, return to 50% of his volunteering/coach capacity with the soccer club (prior to onset of physical and psychosocial HD symptoms), up to 3 days/week

Clinical Impression (Diagnosis and Prognosis)[edit | edit source]

Mr. Johnson is a 38-year-old male, who was diagnosed with an intermediate stage of Huntington’s Disease 4 years ago following the onset of concerning symptoms such as cognition, focus, and general motor clumsiness, which led to his referral for physiotherapy by his primary physician. Mr. Johnson presents with increased error/clumsiness/difficulty during continuous tasks such as walking, and trouble with discrete tasks with fine-motor skills such as gripping and holding things. As well, Mr. Johnson demonstrates signs of chorea and decreased coordination, which is apparent in his job as a gardener, and now manager. Mr. Johnson is likely experiencing these deficits in cognition and motor function as a result of atrophy to the striatum, leading to hyperkinesia. Mr. Johnson has been limited in his ability to do tasks required for work as well as general quality of life and self care. While he is not completely independent, Mr. Johnson is likely to progress on a declining curve of function with his HD diagnosis. Due to the nature of his disease, Mr. Johnson will be closely monitored as falls risks, weakness, emotional volatility, cognitive decline are all possible disease outcomes that can affect the patient. Mr. Johnson deals with emotional trauma associated with his diagnosis and chorea, which is a negative factor for his prognosis. However, aside from his diagnosis, Mr. Johnson is an otherwise healthy male with relevant comorbidities, which is a large positive prognostic factor for his ability to mitigate the progression of the disease and engage in prehabilitation/physiotherapy. While Mr. Johnson will not be cured from HD, he is most definitely an eligible candidate for PT, which will help reduce the impact of the disease by ensuring strength, tone, balance, functional mobility, and ability to perform ADLs in a compensatory manner are mastered. Mr. Johnson will be fitted for a 4 wheeled walker to assist with his imbalance and risk of falls. Mr. Johnson will continue with out-patient rehab on a regular basis until further notice and change in condition and or abilities.

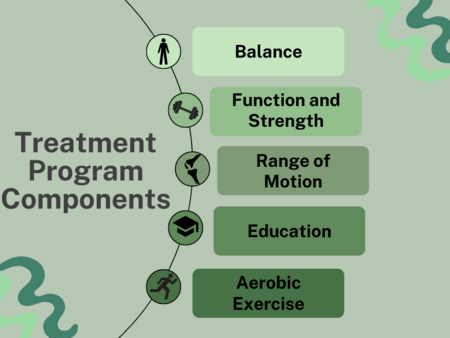

Treatment Plan for Identified Goals[edit | edit source]

The table below is the 12-week treatment plan designed for Mr. Johnson, with each part of the intervention curated to impact his body function, activity, and participation goals set out for physiotherapy. Below the table is the justification for the inclusion of types of exercise and how they are beneficial for Barry, and for others with early-middle stage HD.

| Type | Exercises | Frequency | Intensity | Time | Progression | Target of Intervention |

| Aerobic (within community gym environment)[25] | Stationary cycle | 1x/ week | 65% of age-predicted max HR or RPE of 4-6 | 20 minutes | Increase by 5 minutes as comfortable (reduced RPE) up to 30 minutes | Increase exercise endurance and capacity |

| Anaerobic (within a community gym environment)[25] | Leg press, leg extension, lateral pull down, hamstring curl, calf raises | 1x/ week | 60% of 1-RM for each exercise | 1 sets, 10 reps, | Increase to at least 2 sets, 8-12 reps, 2 minute rest between sets | Increase functional strength and reduce impairment due to reduced conditioning |

| Walking Program (from home)[25] | Gait training regiment with walker | 1x/ week | 4 on RPE | 10 minutes | Increase by 5-minute increments as comfortable (reduced RPE) | Increased gait speed, ambulatory distance |

| Balance (from home)[20] |

|

3x/week | Low to moderate |

|

|

Improve balance |

| Upper and Lower Extremity Range of Motion (ROM) | Stretching at major joints (shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, knee, ankle) | Ideally everyday | Until stretch or discomfort | 30 seconds, twice a day, 3-4 times/week | Progress into deeper stretch as tolerated | Help maintain ROM as disease and weakness progress, and mobility decreases |

In the situation of an adverse event occurring throughout this treatment plan, such as a fall, the exercise volume being too great (as this could be a concern for this population), or unresolving fatigue, there would have to be consultation with Barry about his symptoms and perceived exertion throughout his exercise sessions, and a regression within the effort that he is exerting. Possible modifications that could be made might include increased time for rest, changes to the exercise itself, and reductions in frequency, intensity or volume. An open discussion where Barry is empowered to be involved in the decision-making of his own care would help Barry feel less fatigued (which could attribute to less falls if he is not tired) and more confident in his ability to exercise 3 times a week. Furthermore, Barry would be reassured that such events are to be expected and that improvement rarely occurs in a linear fashion.

Balance[edit | edit source]

Functional exercises focusing on altering the base of support during the performance of upper extremity movements will help improve Barry’s scores on the BBS.[20][26] Activities will incorporate reaching, stepping to applied perturbations, as well as a throwing and catching activity.[27] As Barry progresses through his exercise intervention, progression will occur by going from a wide to narrow base of support, static to dynamic balance exercises, and from low to high centre of gravity.[27]

Function and Strength[edit | edit source]

Functional and strengthening exercises will assist Barry in achieving goals regarding balance, activities of daily living like toileting and walking, and returning to volunteering/coaching. When performing the functional training activities (ex. Sit to Stand), guidelines recommend the patient perform part-task movements by breaking down the entire movement into components.[27] As the patient becomes more independent and skilled in performing certain components, later stages of the movement can be added, and the task can be practiced in a more holistic manner. Verbal and/or auditory cues and compensatory strategies can also be used for the functional tasks as strategies for completing the functional task.[27] In combination with aerobic exercise, strengthening exercise can improve Barry’s exercise capacity and performance as he transitions to the middle stages of Huntington’s Disease.[26]

Range of Motion Exercises[edit | edit source]

Active and passive range of motion exercises can primarily assist Barry with performing functional activities of daily living, balance and postural stability and returning to the activities he enjoys with a reduced falls risk (coaching, volunteering, etc.). These exercises should be performed to try and diminish the limitations in movement caused by the patient’s dystonia, which will ultimately assist him in achieving his goals.[27]

Education[edit | edit source]

Providing education to both Barry and his family will assist him in the process of achieving his goals. Providing Barry with general health promotion and importance of movement education will ensure that he continually performs exercise to progress towards his goals, and will also address his fear of movement.[27] Barry should also receive education on the specific functional, strength, balance, ROM, and aerobic exercises he will be performing to ensure they are completed in an effective and safe manner. Furthermore, progressions and regressions for specific exercises will be taught to ensure the intensity of activities match his capabilities. Education regarding timing of exercise completion on a daily basis will be provided to optimize Barry’s exercise performance and minimize the fatigue experienced.[27] This type of education will allow Barry to have more energy to perform his activities of daily living and participate in hobbies. Finally, education will be provided to Barry’s family regarding guarding and assistance techniques during ambulation. Assistance from family members will ultimately reduce Barry’s falls risk and allow him to focus more on technique and speed/distance of ambulation.[27]

Aerobic Exercise[edit | edit source]

Aerobic exercises will be beneficial to Barry as they will help to improve his endurance of activity and overall exercise capacity. This would be a preventative measure for him as he is already beginning to feel fatigued when completing ADLs and other activities (such as coaching), so by improving his capacity, it will allow him to become more involved with these activities again. With regards to the walking program and its addition to aerobic exercise, the use of a metronome for pacing would be beneficial in step initiation, bigger steps, faster speed, and gait symmetry, all of which contribute to improved gait. Additionally, deep breathing exercises are a great addition while completing these exercises as it aids in respiratory function.[27]

Addressing Participation Restrictions[edit | edit source]

To help address Mr. Johnson’s increased feeling of self-consciousness due to his physical symptoms of HD, a community-based exercise program may be a holistic way to target the physical and psychosocial factors withholding him from having a good quality of life, and progress him towards participating in his volunteering duties with the minor soccer association again in a comfortable capacity for him. A 12-week community-based exercise program for individuals with early-middle stage HD has been shown to have high adherence, medium size effects to mobility and cognition, as well as improved scores within the mental component summary of the SF-36 [25] (which weighs the mental health factors of the score such as vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and emotional well-being more positively), all of which benefit Barry in physical and psychosocial domains. Overall, a 12-week program completed 3-5 days a week that included aerobic and resistive exercises was safe and feasible for those with HD.

Assistive Technology to Treatment Plan[edit | edit source]

Innovative technology mediated tools can be practically implemented alongside an intervention plan for patients with HD to complement and even enhance the approach.[28] Barry Johnson, a 38-year old male, presents with difficulty with various motor tasks, bilateral chorea, decreased coordination, difficulty ambulating, gripping, and holding. These symptoms directly impact Barry’s quality of life, as he often feels self-conscious, would ultimately lead him to physiotherapy to manage these symptoms.

A technology mediated tool could be the use of assistive robotics. In this specific, it is clear that Barry has difficulties with motor tasks and movement, as do most patients with HD. Assistive robotics can help Barry to be physically and socially active, ultimately allowing him to perform activities independently and improve overall quality of life.[29] As previously mentioned, Mr. Johnson has difficulty ambulating and shows signs of chorea, making it difficult for fine-motor movements as well as gripping and holding. As a result, his ADL’s are highly impacted, including his job as a landscaper and office manager. Assistive robotics can provide support when performing these daily activities that might otherwise be too difficult. Specifically, robotic arms and grippers might be helpful in Mr. Johnson’s case to allow him to do tasks such as cooking, cleaning, dressing, etc. Another specific example of an assistive device that would be beneficial in Mr. Johnson’s case would be an exoskeleton.[29] This device has been shown to improve mobility and independence in those with neurodegenerative disorders, and may mitigate the negative health effects of a sedentary lifestyle. Various other uses of an exoskeleton include, encouraging physical activity, early rehabilitation, and supporting daily living tasks in home and community settings.[30] For this reason, as the disease progresses into the more severe and later stages, we believe that Barry would greatly benefit from the use of an exoskeleton.

A variety of challenges may arise when incorporating this assistive technology in clinical practice. As one would assume there may be some difficulties implementing an assistive robotic device in practice. First, it is important to consider the issue of cost and healthcare workload when dealing with these devices.[31] These technologies may be expensive, which may limit access in a clinical setting. Several studies have highlighted that the maintenance, cleaning and repair of exoskeletons can lead to additional costs as well. It is also important to consider time consumption and training that are required to administer assistive devices. The knowledge and proficiency needed to use an exoskeleton is critical, which ultimately means that using one will increase the workload of already inundated staff and increase healthcare costs needed to provide this education.[31] Some ways to mitigate this challenge could be to research funding opportunities. Options such as research grant programs, government agencies, and private foundations may help with the barrier of cost. Insurance coverage, non-profit organizations, buying used devices, are all options to mitigate this barrier to assistive robotic devices. To mitigate healthcare workload, it is vital to develop clear and concise training materials to avoid unnecessary time wasted. Efficient and effective training to patients and healthcare staff is extremely important. Another potential method would be the training of a core group of specialists who can provide ongoing training to help reduce time and resources required to train users.

Another challenge with the implementation of assistive technology and robotics is the device adaptability to the user. Adaptivity refers to the ability of devices to adjust to variations in their surroundings, such as user behavior, circumstances, personal choices, or external factors. These devices require contextual information alongside a model of the user to ensure the correct adaption process. This is often viewed as a machine learning problem.[29] Therefore, it might be difficult for wearable assistive robots to deal with the level of changes that might be expected in outdoor environments and may not accurately capture the complexities or diversity of many use cases. There are ways to mitigate these problems, namely hybrid solutions. Hybrid solutions utilize initial knowledge to form templates or detect initial activities, while any recently detected activities are saved for subsequent labeling, which may involve the user's active involvement.[29] Although there are various barriers with the incorporation of assistive robotic devices in practice, it is possible to mitigate these barriers if the problem is approached correctly.

Interdisciplinary Care Team: Management and Referrals[edit | edit source]

Clinical Psychologist[edit | edit source]

It is strongly recommended that Mr. Johnson be referred to a clinical psychologist, as he is exhibiting symptoms that strongly align with the expertise of this healthcare profession. Mr. Johnson has been experiencing depression, irritability, and agitation since the onset of his diagnosis of HD, as well as increased marital issues and forgetfulness. These issues fall objectively within the scope of practice of clinical psychologists, and their expertise would be valuable in helping Mr. Johnson manage his symptoms and improve his overall quality of life.[32] A clinical psychologist may provide many services to Barry, including psychological assessments, psychotherapy, and cognitive-behavioral interventions.[32] They can also provide support and guidance to Mr. Johnson’s family members and caregivers, who may be struggling with the challenges of the disease.

Referral to clinical psychologist:

I strongly recommend that Mr. Johnson attend your services due to his symptoms of depression, irritability, agitation, forgetfulness, and marital issues. It should be noted that Mr. Johnson was prescribed 25 mg of Valium (Diazepam) per day following the onset of HD and increase in depressive symptoms as well as some initiation of chorea and dystonia. Reassessment of Mr. Johnson’s diagnosis of depression and other surrounding medical issues are indicated. It is also asked that you consider Mr. Johnson’s family members and caregivers, who may also be struggling with the challenge of the disease. It is my recommendation that Mr. Johnson is referred to a clinical psychologist who has experience working with individuals with HD, and can help coordinate care between the various healthcare providers involved in his treatment.

Occupational Therapist[edit | edit source]

It is recommended that Mr. Johnson be referred to an Occupational Therapist (OT). It was noted that Mr. Johnson often feels cloudy in thought, sometimes even forgetful when taking care of personal and work-related responsibilities. These signs are indicative of cognitive decline, which can be assessed by an OT. An OT can also work alongside Mr. Johnson to develop strategies and adaptations that will allow him to continue to participate in his job, social life, and daily activities despite his HD symptoms.[27] The OT can provide access to home care services, potentially visiting Mr. Johnson’s home to assess his accessibility. They can provide services that ensure this is a comfortable environment for him to live and progress with his disease. They can also provide training and education to Mr. Johnson’s family members and caregivers on how to best support him in his daily activities.[27] By addressing these aspects of Mr. Johnson’s condition, he can hopefully improve his overall quality of life.

Speech Language Pathologist[edit | edit source]

It is recommended that Mr. Johnson be referred to a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP). Mr. Johnson’s reported cognitive symptoms such as feeling cloudy in thought and forgetfulness may indicate possible language and communication difficulties. Moreover, persons with HD often have and or develop speech, language, and communication disabilities.[27] This neurodegenerative disorder will, at some point, change an individual’s ability to speak clearly, understand language, and communicate effectively. An SLP can conduct a comprehensive evaluation of Mr. Johnson’s language, communication, and cognitive abilities to determine if there are any underlying deficits that may be impacting his ability to communicate effectively.[33] Additionally, an SLP can provide therapy to address any identified deficits and help Mr. Johnson improve his overall communication and cognitive function.[33]

Discussion[edit | edit source]

Our case study presented Barry Johnson, a fictional 38-year old male who was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease (HD). Current, Mr. Johnson is in the early intermediate stages of the disease, hallmarked by his increased chorea, depression, cognitive decline, and gait instability. During the subjective assessment, knowledge on his current symptoms, activity limitations, social engagement, and relevant health habits pertaining to HD were obtained. Mr. Johnson clearly outlined his intention for seeking out physical therapy, as well as the goals he wanted to achieve with treatment. On objective assessment, Mr. Johnson was assessed for his strength using MMTs, balance using the Berg Balance Scale, gait using the Timed-Up and Go and Gait Speed tests, Emotional and Cognitive status using the SF-36, and last screened for hypertension as a critical comorbidity that can exacerbate symptoms and disease severity. Mr. Johnson scored mid to poor ranges on all tests, indicating increased weakness, moderate falls risk, impaired ability to engage in ADLs and social contexts of life, as well as cognitive and emotional decline.

A treatment plan was devised for Mr. Johnson in order to target deficits across all domains. The treatment looked to both increase clinical measures such as strength, balance, and aerobic capacity, as well as client-centered functional outcomes such as increased ability to perform ADLs, increased independence and confidence in social and work-related contexts. The developed treatment plan not only targets multiple domains of the ICF and current areas of difficulty for Mr. Johnson, but was developed in a way to attenuate inevitable disease progression and ensure long lasting quality of life and functional independence. Designing a treatment plan for individuals with HD should be highly individualized, as each patient provides a unique clinical presentation and personal goals. Furthermore, multiple assistive technologies such as wearable robotics and exoskeletons and other interdisciplinary health care workers (i.e. occupational therapist, speech-language pathologist, and clinical psychologist) were identified to supplement the physiotherapy treatment. While physiotherapy can provide an immense amount of support to Mr. Johnson and his diagnosis of HD, working alongside other professionals will only increase its effectiveness, especially as the disease inevitably progresses.

The current focus of physiotherapy for patients with HD continues to change as the field of research continues to gain more knowledge about the pathophysiology and disease presentation. Treatment focusing on balance, gait, aerobic capacity, and strength help the patient maintain physical function and mobility, which then directly allows the patient to maintain a level of indepence, ability to engage in activities of daily living, and enable improved self-confidence and self-efficacy. While there is currently no cure for HD, physiotherapy treatment supplemented with support from an interdisciplinary healthcare team and other assistive technologies can help patients effectively manage its symptoms and enable the patient to function with a quality of life.[34] Further research is needed to identify the effects of the disease and innovative therapeutic interventions that can help attenuate disease progression.

Multiple Choice Questions[edit | edit source]

1. Which of the following are not part of the typical triad of clinical findings for Huntington’s Disease?

a) Chorea

b) Dementia

c) Rigidity

d) Freezing of Gait

2. Which of the following outcome measures would be useful in an objective assessment of Huntington’s Disease

a) Berg Balance Scale (BBS)

b) Huntington's Disease Activities of Daily Living (HD-ADL) Scale

c) Short Form 36 (SF-36)

d) 2 of the above

e) All of the above

3. Which of the following statements regarding treatment planning for Huntington’s Disease is false?

a) Anaerobic training is contraindicated for individuals with Huntington’s disease as it exacerbates symptoms and accelerates disease progression

b) The use of a metronome for pacing of gait would be beneficial in step initiation, bigger steps, faster speed, and gait symmetry

c) ROM exercises should be performed to try and diminish the limitations in movement caused by the patient’s dystonia

d) All of the above are true

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Ghosh R, Tabrizi SJ. Clinical Features of Huntington’s Disease. Polyglutamine Disorders. 2018;1049:1–28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Entry - #143100 - HUNTINGTON DISEASE; HD - OMIM [Internet]. www.omim.org. 2022 [cited 2023 May 12]. Available from: https://www.omim.org/entry/143100#editHistory

- ↑ McColgan P, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. European Journal of Neurology. 2017 Sep 22;25(1):24–34.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cepeda C, Tong X. Huntington’s disease: From basic science to therapeutics. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics [Internet]. 2018 Mar 26 [cited 2021 Feb 18];24(4):247–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489829/?log

- ↑ Chouksey A, Pandey E. Phenotypic Variability in Huntington’s Disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23(2):153–4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Matz OC, Spocter M. The Effect of Huntington’s Disease on the Basal Nuclei: A Review. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Apr 25;14(4). Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/91576-the-effect-of-huntingtons-disease-on-the-basal-nuclei-a-review

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Kirkwood SC, Su JL, Conneally PM, Foroud T. Progression of Symptoms in the Early and Middle Stages of Huntington Disease. Archives of Neurology [Internet]. 2001 Feb 1;58(2):273. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/article-abstract/778574

- ↑ Nance MA, Sanders G. Characteristics of individuals with Huntington disease in long-term care. Movement Disorders. 1996 Sep;11(5):542–8.

- ↑ Videnovic A. Treatment of Huntington disease [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2013 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3677041/

- ↑ Quinn L;Kegelmeyer D;Kloos A;Rao AK;Busse M;Fritz NE; Clinical recommendations to guide Physical Therapy Practice for Huntington disease [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31907286/

- ↑ Busse M, Quinn L, Khalil H, McEwan K, the Outcome Measures Subgroup of the European Huntington’s Disease Network. Optimising mobility outcome measures in Huntington’s disease [Internet]. IOS Press; 2014 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-140091

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Busse ME, Wiles CM, Rosser AE. Mobility and falls in people with Huntington’s disease [Internet]. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2009 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.147793

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Quinn L, Khalil H, Dawes H, Fritz NE, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos AD, et al. Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change of Physical Performance Measures in Individuals With Pre-manifest and Manifest Huntington Disease. Physical Therapy. 2013 Mar 21;93(7):942–56.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Moore JL, Potter K, Blankshain K, Kaplan SL, OʼDwyer LC, Sullivan JE. A Core Set of Outcome Measures for Adults With Neurologic Conditions Undergoing Rehabilitation. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2018 Jun;42(3):1. Available from: https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/a-core-set-of-outcome-measures-for-adults-with-neurologic-conditi

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ho AK, Robbins AOG, Walters SJ, Kaptoge S, Sahakian BJ, Barker RA. Health-related quality of life in Huntington’s disease: a comparison of two generic instruments, SF-36 and SIP. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society [Internet]. 2004 Nov 1 [cited 2023 May 11];19(11):1341–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15389986/

- ↑ Stevenson JJ, Rosser AE, Hart E, Murphy K. Hypertension, antihypertensive use and the delayed‐onset of Huntington ... [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://movementdisorders.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/mds.27976

- ↑ Bylsma FW, Rothlind JC, Hall ML, Folstein SE, Brandt J. Assessment of adaptive functioning in huntington’s disease. Movement Disorders. 1993 Jan 1;8(2):183–90.

- ↑ FACTSHEETS FOR HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS: Physiotherapy Outcome Measures in Huntington Disease [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.huntingtonsociety.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/PysioTherapy_outcome_measures_health_prof_FS.pdf

- ↑ Cruickshank TM, Reyes AP, Penailillo LE, Pulverenti T, Bartlett DM, Zaenker P, Blazevich AJ, Newton RU, Thompson JA, Lo J, Ziman MR. Effects of multidisciplinary therapy on physical function in Huntington's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2018 Dec;138(6):500-7.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Khalil H, Quinn L, van Deursen R, Dawes H, Playle R, Rosser A, Busse M. What effect does a structured home-based exercise programme have on people with Huntington’s disease? A randomized, controlled pilot study. Clinical rehabilitation. 2013 Jul;27(7):646-58.

- ↑ Panzera R, Salomonczyk D, Pirogovosky E, Simmons R, Goldstein J, Corey-Bloom J, Gilbert PE. Postural deficits in Huntington's disease when performing motor skills involved in daily living. Gait & posture. 2011 Mar 1;33(3):457-61.

- ↑ Meretta BM, Whitney SL, Marchetti GF, Sparto PJ, Muirhead RJ. The five times sit to stand test: responsiveness to change and concurrent validity in adults undergoing vestibular rehabilitation. Journal of Vestibular Research. 2006 Jan 1;16(4-5):233-43.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Bilney B, Pearce A. Rehabilitation of Huntington’s disease. Rehabilitation in movement disorders. 2013 May 23:162.

- ↑ Kloos AD, Kegelmeyer DA, White SE, Kostyk SK. The impact of different types of assistive devices on gait measures and safety in Huntington's disease. PloS one. 2012 Feb 17;7(2):e30903.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Busse M, Quinn L, Debono K, Jones K, Collett J, Playle R, et al. A randomized feasibility study of a 12-week community-based exercise program for people with Huntington’s disease. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2013 Dec;37(4):149–58.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Fritz N, Rao AK, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos A, Busse M, Hartel L, et al. Physical Therapy and Exercise Interventions in Huntington’s Disease: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. J Huntingtons Dis [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 May 11];6(3):217. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5676854/

- ↑ 27.00 27.01 27.02 27.03 27.04 27.05 27.06 27.07 27.08 27.09 27.10 27.11 Quinn L, Busse M. Physiotherapy clinical guidelines for Huntington’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2012 Feb;2(1):21–31.

- ↑ Brose SW, Weber DJ, Salatin BA, Grindle GG, Wang H, Vazquez JJ, Cooper RA. The role of assistive robotics in the lives of persons with disability. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2010 Jun 1;89(6):509-21.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Martinez-Hernandez U, Metcalfe B, Assaf T, Jabban L, Male J, Zhang D. Wearable assistive robotics: A perspective on current challenges and future trends. Sensors. 2021 Oct 12;21(20):6751.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Fernández A, Lobo-Prat J, Font-Llagunes JM. Systematic review on wearable lower-limb exoskeletons for gait training in neuromuscular impairments. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2021 Dec;18(1):1-21.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hung L, Liu C, Woldum E, Au-Yeung A, Berndt A, Wallsworth C, Horne N, Gregorio M, Mann J, Chaudhury H. The benefits of and barriers to using a social robot PARO in care settings: a scoping review. BMC geriatrics. 2019 Dec;19:1-0.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rosenblatt A, Ranen NG, Nance MA, Paulsen JS. A Physician’s Guide to the Management of Huntington’s Disease. Huntington’s Disease Society of America, New York. 1999.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Grimstvedt TN, Miller JU, Van Walsem MR, Feragen KJ. Speech and language difficulties in Huntington's disease: A qualitative study of patients’ and professional caregivers’ experiences. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2021 Mar;56(2):330-45.

- ↑ Novak MJ, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease. Bmj. 2010 Jun 30;340.