General Overview of Rheumatoid Arthritis for Rehabilitation Professionals

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a “chronic inflammatory autoimmune systemic disease that usually presents with joint inflammation leading to pain, fatigue, and impaired physical functioning and work productivity, all of which negatively impact health-related quality of life.”[1]

RA commonly affects the hands, wrists, shoulders, elbows, knees, ankles and feet.[2] As it is a systemic condition, it can significantly affect a number of body systems, including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems.[2][3][4] Without adequate treatment, RA can cause long-term disability, pain and premature death.[5] [6] While pharmacological management is the mainstay treatment for RA,[5] rehabilitation professionals can play a role in the non-pharmacological management of this condition.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

RA affects around 1% of the global population,[3] and up to 3% of older persons.[5] It is 2-3 times more likely to occur in females.[6] However, with improving medical management, the severity, mortality and associated comorbidities appear to be decreasing.[7]

The peak age of onset of RA tends to be in younger populations (approx 30-60 years), although the exact age ranges given in the literature vary:[8][9]

- younger-onset RA is distinguished from elderly-onset RA (i.e. after 60 years) in the literature[8][10]

- Slobodin[11] notes that the peak age of onset of RA has increased

- in the 1930s, peak age was in individuals in their 30s

- by the 2010s, peak age was in individuals in their 50s or 60s

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

RA is a multifactorial disease that has been linked to various genetic, environmental and other factors:[3]

- genetic factors: the HLA-DRB1 alleles are linked with an increased risk of developing RA[12]

- certain environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals, such as:

- hormonal factors:[13]

- effects of oestrogen on immune function are believed to play a role in female predominance in RA

- other sex-related factors are probably involved as well

Clinical Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Common RA joint symptoms include:[2][14]

- symmetrical joint pain (wrists, fingers (MCP), knees, ankles, feet and upper cervical spine commonly affected)

- morning stiffness that lasts for more than one hour or stiffness after inactivity

- joints may feel warm and tender after more than one hour of inactivity

- loss of / limitations in range of motion

- deformity

Typical Joint Deformities[edit | edit source]

Cervical spine: the prevalence of atlantoaxial instability (AAI) in individuals with RA is 40-85%[15]

- hypermobility between C1 and C2

- transverse ligament laxity

- subluxation risk

- possible neurologic involvement

Hand:[14]

- swan neck deformity

- boutonniere deformity

- ulnar drift

- thumb metacarpophalangeal flexion with interphalangeal hyperextension

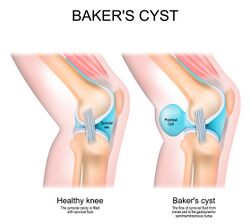

Knee:[14]

- genu valgus

- Baker cyst

Ankle / foot:[14]

- pronation

- hallux valgus

- claw toes

Other symptoms and extra-articular manifestations:[2][3][14][16]

- pulmonary issues (e.g. pleuritis, pleural effusions, pulmonary fibrosis, interstitial lung disease and arteritis[3])

- cardiac issues (e.g. atherosclerosis, arterial stiffness, coronary arteritis, congestive heart failure, valvular disease and fibrinous pericarditis[3])

- Felty’s syndrome (i.e. low white blood cell count, spleen enlargement and rheumatoid arthritis[17])

- dry eyes and mouth (Sjögren's syndrome)

- numbness, tingling, or burning sensation in the hands and feet

- sleep difficulties

- rheumatic nodules

- these occur more in individuals with seropositive RA with erosive disease[3] (see Pathophysiology section for information on seropositive / seronegative RA)

- fatigue

- reduced cognitive function

- sarcopenia

- osteoporosis

- vasculitis (can result in “skin manifestations, gastrointestinal complications, cardiac disease, and pulmonary manifestations”[3])

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

There are two main subtypes of RA:[16][18]

- seropositive RA:[18]

- autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), are present

- autoantibodies are present in 50% of individuals with early RA, and up to 80% of individuals with established RA

- ACPAs are present in around 67% of individuals with RA[16]

- seronegative RA[18]

Basic Overview of Rheumatoid Arthritis Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of RA is complex. The following points describe the pathophysiology of seropositive RA. Please note that patients can have different pathogenic pathways and cell lineages:[13][16][21][22]

- a genetically predisposed individual is exposed to an environmental trigger (e.g. smoking or infection) - this can cause disordered immunity

- disordered immunity may lead to the citrullination of some proteins - citrullination is when the amino acid arginine converts to citrulline[23]

- antigen-presenting cells recognise these modified proteins as foreign and transport them to lymph nodes and mucosal and lymphoid tissues, where they activate CD4+ T-helper cells

- this stimulates B-cells to proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells

- these plasma cells produce autoantibodies (i.e. ACPAs and rheumatoid factor)

- autoantibodies can then migrate to the joint synovium

- symmetrical swelling in the small joints is the “external reflection of synovial membrane inflammation following immune activation”[16]

- once in the synovium, autoantibodies start producing proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. interferon-gamma and interleukins)

- this causes macrophages, monocytes and synovial fibroblasts to release cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF alpha), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-1

- synovial fibroblasts then start to proliferate, which increases joint inflammation (i.e. synovial hyperplasia)

- proliferating synovial cells produce a pannus, which is a thickened, synovial membrane made of destructive granulation tissue

- this pannus causes the erosion of cartilage and bone

- activated synovial cells also produce proteases which break down cartilage

- inflammatory cytokines cause increased activity of osteoclasts (cells that break down bone) - there is also decreased activity of osteoblasts (cells that repair / form new bone)

- this leads to articular bone loss and osteoporosis

- ACPAs and RF form immune complexes that activate the complement system (an important part of the innate immune system[24]), which leads to chronic inflammation

- angiogenesis (i.e. the formation of new capillaries from existing vasculature[25]), occurs alongside chronic inflammation - this enables more inflammatory cells to travel to the joints

- this produces additional pro-inflammatory factors, which exacerbate existing processes

- as RA progresses, multiple joints on both sides of the body are affected

- inflammatory cytokines also spread to other parts of the body, causing extra-articular symptoms, such as

- vasculitis

- rheumatoid nodules

- protein breakdown in skeletal muscle

- RA can wax/wane, with various exacerbations (flares) and periods of remission[26]

This complex process is explained in detail in Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies[16] and in the following videos:

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

The following lab tests help in the diagnosis of seropositive RA:[14]

- rheumatoid factor

- around 80% of individuals with RA have rheumatoid factor

- around a 5% false positive rate

- anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP) test

Other tests include:[14]

- C-reactive protein (CRP): general inflammatory marker

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- relative activity of the disease process

- non-specific measure of inflammation

- complete blood count

- x-rays

- will not show early onset RA[30]

- during the later stages, the following may be evident on x-ray:

- irregular joint surfaces

- decreased joint space

- abnormal joint alignment

- synovial fluid analysis

- increased white blood cell count

- increased collagenase

- increased debris (proteins)

Diagnostic Criteria[edit | edit source]

1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for RA are as follows:[31]

- morning stiffness in and around joints that lasts for at least one hour

- soft tissue swelling of three or more joint areas

- swelling of the proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, or wrist joints

- symmetric swelling

- rheumatoid nodules

- presence of rheumatoid factor

- radiographic erosions and/or periarticular osteopenia in hand and/or wrist joints

The first four criteria must have been present for at least six weeks. In this system, rheumatoid arthritis = having four or more of the above criteria.[31]

While these criteria “are well accepted as providing the benchmark for disease definition”,[30] there are limitations because they are designed to differentiate individuals with established RA from other rheumatological conditions. They don’t, therefore, help identify individuals with early RA.[30]

2010 ACR/ EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Diagnostic Criteria for RA are as follows:[30]

- joint involvement: 1 large joint = 0; 2-10 large joints = 1; 1-3 small joints (with or without large joint involvement) = 2; 4-10 small joints (with or without large joint involvement) = 3; >10 joints (a least 1 small joint) = 5

- serology (at least one test result is needed for classification): negative rheumatoid factor and negative ACPA = 0; low-positive RF or low-positive ACPA = 2; high-positive RF or high-positive ACPA = 3

- acute-phase reactants (at least one test result is needed for classification): normal CRP and normal ESR = 0; abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR = 1

- duration of symptoms: < 6 weeks = 0; 6 or more weeks = 1

A score of 6 or more is required for an individual to be classified as having RA.[30]

Click here to see the 2010 ACR/ EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Diagnostic Criteria for RA in table form.

Treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis[edit | edit source]

There have been many developments in the treatment of RA in recent decades.[2] While the primary management is pharmacological, various non-pharmacological interventions also play a role, including patient education, exercise, physiotherapy and occupational therapy.[32]

Pharmacological Management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacological management aims to decrease join inflammation and inhibit disease progression.[14]

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDS)[edit | edit source]

“Early diagnosis and intervention with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) remain the cornerstone of treatment to control inflammation, prevent joint and organ damage, and reduce the risk of death.”

DMARDS include 1) conventional synthetic DMARDs (eg, methotrexate), 2) targeted synthetic DMARDs (eg, Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors), and 3) biological DMARDs (eg, anti-tumor necrosis factor [TNF] biologics or non-TNF biologics).

- low-dose methotrexate is the mainstay initial treatment for RA

- 25-40% of patients will experience significant improvements with methotrexate alone

- if patients have inadequate responses, other agents (e.g. JAK inhibitor or biological agent) can be introduced[13]

The following article provides a detailed discussion of DMARDs for RA: Current therapeutic options in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[32] The following optional videos provide a simple summary of DMARDs for RA:

Other Medications[edit | edit source]

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): e.g. ibuprofen, naproxen[14]

- decrease pain and improve function by decreasing acute inflammation

- may help with symptoms, but do not change the disease course in RA[35]

Corticosteroids: e.g. dexamethasone, cortisone[14]

- have a number of side effects

- may help reduce symptoms, but do not change the disease course in RA[35]

Non-pharmacological Management[edit | edit source]

“Despite the availability of effective medication, there is a substantial proportion of patients with persisting or recurring disease activity, with or without joint damage. Moreover, the evidence for an increased cardiovascular risk in patients with inflammatory joint diseases is growing. As a result, many patients are in need of additional, nonpharmacological treatment, including physical therapy.”[2]

While rehabilitation cannot influence the disease process of RA, it can help with function!

NICE[36] recommends that individuals with RA receive input from various members of the rehabilitation team, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, podiatry and psychology.

Exercise / Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

There is evidence that increasing physical activity levels / exercise can help with symptoms and reduce the impact of systemic manifestations of RA.[37] However, in general, people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are less active than healthy controls,[38] engaging in less physical activity than is recommended in international guidelines (especially in those aged <55 years).[39]

The following optional video will help you to learn more about exercise for rheumatoid arthritis. Key points from the video include:[40]

- all types of exercise produce similar benefits, so consider your patient’s preferences

- exercise must be individualised to suit the patient’s requirements (e.g. available time, interests, access to equipment, function, etc.)

- look at the current function and compare this to your patient's required function

- consider general physical activity levels alongside exercise plans

- include strength, range and cardiovascular components in an exercise plan

Peter et al.[2] produced a clinical practice guideline detailing the physiotherapy assessment and management of individuals with RA, which is available here: Clinical practice guideline for physical therapist management of people with rheumatoid arthritis.

The Strengthening And Stretching for Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand (SARAH) programme is considered a clinically effective and cost-effective adjunct treatment to improving hand function in individuals with RA.[41][42] More information on this programme is available here and in the following video:

Other Non-pharmacological Interventions[edit | edit source]

- Patient education (relevant at all stages of the disease course)[44] [2][14]

- include information on RA and the importance of exercise and a healthy lifestyle

- strategies to reduce disability (within your specific scope of practice) - e.g. distributing load, using assistive devices

- support the patient to be physically active but distribute energy over the day / week based on fatigue

- acknowledge and address barriers to exercise / physical activity

- barriers can include a lack of knowledge, lack of social support, pain, fatigue, fear that exercise will damage joints, etc.

- Joint protection[14]

- avoid positions of deformity

- adopt the most stable positions

- avoid repetitive tasks

- Energy conservation

- consider systemic complications, e.g. reduced cardiovascular function

- Assistive devices

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

- Peter WF, Swart NM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapist management of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther. 2021 Aug 1;101(8):pzab127.

- Majnik J, Császár-Nagy N, Böcskei G, Bender T, Nagy G. Non-pharmacological treatment in difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Aug 29;9:991677. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.991677. PMID: 36106320; PMCID: PMC9465607.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management: NICE guideline [NG100]. 2018 (updated 2020).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Küçükdeveci AA, Turan BK, Arienti C, Negrini S. Overview of Cochrane Systematic Reviews of rehabilitation interventions for persons with rheumatoid arthritis: a mapping synthesis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2023 Apr;59(2):259-69.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Peter WF, Swart NM, Meerhoff GA, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapist management of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther. 2021 Aug 1;101(8):pzab127.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Radu AF, Bungau SG. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Cells. 2021 Oct 23;10(11):2857.

- ↑ Metsios GS, Kitas GD. Physical activity, exercise and rheumatoid arthritis: Effectiveness, mechanisms and implementation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Oct;32(5):669-82.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Turk MA, Liu Y, Pope JE. Non-pharmacological interventions in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2023 Jun;22(6):103323.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis, 1990-2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 Sep 25;5(10):e594-e610.

- ↑ Finckh A, Gilbert B, Hodkinson B, Bae SC, Thomas R, Deane KD, et al. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022 Oct;18(10):591-602.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Yazici Y, Paget SA. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000 Aug;26(3):517-26.

- ↑ Bullock J, Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM, Ahmed SS, Do DP, Ansari RA, Ahmed J. Rheumatoid arthritis: A brief overview of the treatment. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(6):501-7.

- ↑ Pavlov-Dolijanovic S, Bogojevic M, Nozica-Radulovic T, Radunovic G, Mujovic N. Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis: characteristics and treatment options. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 Oct 23;59(10):1878.

- ↑ Slobodin G. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Slobodin G, Shoenfeld Y, editors. Rheumatic Disease in Geriatrics. Springer, Cham, 2020.

- ↑ Chauhan K, Jandu JS, Brent LH, et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis. [Updated 2023 May 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441999/

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Gravallese EM, Firestein GS. Rheumatoid arthritis - common origins, divergent mechanisms. N Engl J Med. 2023 Feb 9;388(6):529-42.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 Cunningham S. Rheumatoid Arthritis Course. Physiopedia Plus, 2024.

- ↑ Cunningham S. Upper cervical instability associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. J Man Manip Ther. 2016 Jul;24(3):151-7.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 Guo Q, Wang Y, Xu D, Nossent J, Pavlos NJ, Xu J. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res. 2018 Apr 27;6:15.

- ↑ Arthritis Society Canada. Felty's syndrome. Available from: https://arthritis.ca/about-arthritis/arthritis-types-(a-z)/types/felty-s-syndrome (last accessed 22 May 2024).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Volkov M, van Schie KA, van der Woude D. Autoantibodies and B cells: The ABC of rheumatoid arthritis pathophysiology. Immunol Rev. 2020 Mar;294(1):148-63.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Carbonell-Bobadilla N, Soto-Fajardo C, Amezcua-Guerra LM, Batres-Marroquín AB, Vargas T, et al. Patients with seronegative rheumatoid arthritis have a different phenotype than seropositive patients: A clinical and ultrasound study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Aug 16;9:978351.

- ↑ NEJM Group. What Is Rheumatoid Arthritis? | NEJM. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e_NZk8nFSPA (last accessed 23 May 2024).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 NEJM Group. What Is Rheumatoid Arthritis? | NEJM. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e_NZk8nFSPA [last accessed 23/05/2025]

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Osmosis from Elsevier. Rheumatoid arthritis - causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EB5zxdAQGzU [last accessed 23/05/2024]

- ↑ Gazitt T, Lood C, Elkon KB. Citrullination in rheumatoid arthritis-a process promoted by neutrophil lysis? Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2016 Oct 31;7(4):e0027.

- ↑ Holers VM, Banda NK. Complement in the initiation and evolution of rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2018 May 28;9:1057.

- ↑ Elshabrawy HA, Chen Z, Volin MV, Ravella S, Virupannavar S, Shahrara S. The pathogenic role of angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Angiogenesis. 2015 Oct;18(4):433-48.

- ↑ Orange DE, Yao V, Sawicka K, Fak J, Frank MO, Parveen S, et al. RNA identification of PRIME cells predicting rheumatoid arthritis flares. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 16;383(3):218-28.

- ↑ Melbourne Pathology. Anti-CCP Insight – March 2019. Available from: https://www.mps.com.au/media/6479/mp_insight_anti-ccp_final-in-house-march-19.pdf (last accessed 8 June 2024).

- ↑ Cho J, Pyo JY, Fadriquela A, Uh Y, Lee JH. Comparison of the analytical and clinical performances of four anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody assays for diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021 Feb;40(2):565-573.

- ↑ Zhu JN, Nie LY, Lu XY, Wu HX. Meta-analysis: compared with anti-CCP and rheumatoid factor, could anti-MCV be the next biomarker in the rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019 Oct 25;57(11):1668-79.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2569-81.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Mar;31(3):315-24.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Köhler BM, Günther J, Kaudewitz D, Lorenz HM. Current therapeutic options in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Med. 2019 Jun 28;8(7):938.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Rheumatology. Rheumatoid Arthritis - Treatment | Johns Hopkins. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kDbztlKXKM [last accessed 23/05/2024]

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Rheumatology. Treatment Options for Rheumatoid Arthritis | Johns Hopkins Rheumatology. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSOhxIJCV-o [last accessed 23/05/2024]

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center. Rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Available from: https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/rheumatoid-arthritis/ra-treatment/ (last accessed 25 May 2024).

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management: NICE guideline [NG100]. 2018 (updated 2020). Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100/ [accessed 24 May 2024].

- ↑ Metsios GS, Kitas GD. Physical activity, exercise and rheumatoid arthritis: Effectiveness, mechanisms and implementation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Oct;32(5):669-82.

- ↑ Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, et al. 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Sep;77(9):1251-60.

- ↑ Lange E, Kucharski D, Svedlund S, Svensson K, Bertholds G, Gjertsson I, Mannerkorpi K. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Jan;71(1):61-70.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 The Rheumatology Physio. Exercise and rheumatoid arthritis webinar. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdtXacpfBg8 [last accessed 25 May 2024].

- ↑ NDORMS. SARAH Implementation. Available from: https://www.ndorms.ox.ac.uk/rrio/sarah-implementation (last accessed 24 May 2024).

- ↑ Lamb SE, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, Adams J, Dosanjh S, Dritsaki M, et al. Exercises to improve function of the rheumatoid hand (SARAH): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jan 31;385(9966):421-9.

- ↑ British Society for Rheumatology. Hand exercises for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1pNhMkJHhg [last accessed 24/05/2024]

- ↑ Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, Andersen L, Bode C, Boström C, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jun;74(6):954-62.