Female Athlete Triad and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

Original Editor - Wanda van Niekerk based on the course by Jennifer Bell

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

In recent years, there has been an upward trend in participation in women's sports. Efforts are made to engage women of all ages in sport and exercise and this is seen in the increase of female athletes being included in national teams at events such as the Olympic games.

The increased awareness of the female athlete as a unique population is highlighted in recent research. A woman's body responds differently to exercise than a male's body, yet much of the research informing sports medicine is based on studies investigating male participants. There are unique anatomical and physiological differences between sexes and this needs to be taken into consideration. It is crucial to understand the unique and individual considerations for the female athlete across all the various transitions in their lifespan. This is necessary for performance and the athlete's career.

Understanding the Female Developmental Process[edit | edit source]

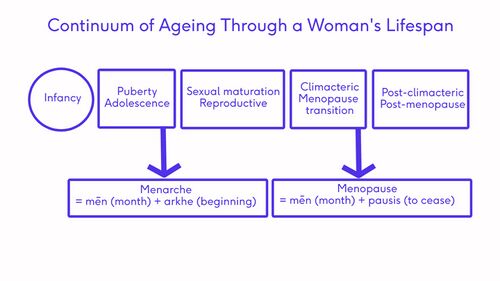

The diagram below depicts the transitions a female will pass through in an average life span. Common signs and symptoms for the onset of each of these transitions are listed below.

Puberty[edit | edit source]

- Puberty – transitional stage from childhood up to menarche[1][2]

- This happens to everyone, but menarche is unique to females.

- Other signs of puberty in females include:

- breast development

- pubic hair growth

- vaginal mucosal changes

- growth spurt

- increase in body odour

- oilier hair and skin

- Precocious puberty – when puberty happens before the age of 8 years in females and 9 years in males. Assessment by a physician is required when this occurs.[3]

Menarche[edit | edit source]

- Menarche occurs at the beginning of the reproductive stage and is marked by the first menstrual period. It occurs during the late stages of puberty, typically between the ages of 10 and 16.[4]

- Irregular menstrual cycle initially in the first two years of menstruation

- No menstruation or signs of puberty by the age of 15 requires further evaluation[5]

Menstruation[edit | edit source]

A menstrual period is defined as the monthly shedding of the functional layer (the endometrial lining) of the uterus.[6] The menstrual cycle lasts between 25 and 35 days and an "ideal" menstrual cycle is 28 days long. Day 1 is the menses (when the bleeding starts). The bleeding commonly lasts for 5 to 7 days. Menses is included in the follicular phase. After the cessation of bleeding, the endometrium starts to thicken until the egg is released (ovulation). The next phase is the luteal phase and during this phase, the egg can either be fertilised and implanted in the thickened endometrium. If the egg is not fertilised, the egg and the thickened part of the endometrium are broken down and expelled. This is the beginning of menses (day 1).

Review Female Anatomy: Female Genital Tract

Read more: Menarche to Menopause and Menstruation and Menstrual Rehab

Important definitions:

- Eumenorrhea - "normal" menstruation, the cycle lasts between 25 and 35 days, with typical bleeding lasting between 4 and 7 days and a loss of approximately 30 to 60 ml of blood[5]

- Oligomenorrhea - abnormal menstruation - extremely heavy flow, a period lasting for longer than 7 days and fluctuations in the length of cycles (can be longer or shorter cycles)[8]

- Amenorrhea- the absence of menarche onset

- Primary amenorrhea - non-menstruation cycle by the age of 16[9]

- Secondary amenorrhea - history of menstruation followed by 3 or more months without menstrual cycle in someone who was previously menstruating regularly or more than 6 months in someone who has irregular cycles[10]

Perimenopause[edit | edit source]

- Period of approximately 4 years leading up to menopause ("period prior to cessation of menses")[11]

- Increasing variability in length of menstrual cycle[12]

- Hormonal fluctuations[12]

- Hot flashes[12]

- Sleep disturbances[12]

- Mood changes[12]

- Vaginal dryness and painful sex[12]

Menopause[edit | edit source]

- The average age of menopause is 51.4 years old[5][12]

- Menopause is 12 months from the last menstrual cycle[13]

- Post-menopause is the rest of a woman's life after menstruation has ended[13]

- Female sex hormone levels such as oestrogen levels are significantly lower in post-menopause phase[14]

- Health issues to be aware of when women are going through menopause:

Female Athlete Triad[edit | edit source]

The female athlete triad refers to this interrelationship between the following components[18]:

- menstrual dysfunction

- low bone mineral density

- low energy availability (with or without disordered eating or an eating disorder)

Awareness of Clinical Picture[edit | edit source]

- Female engaging in high levels of exercise

- Low caloric intake

- Development of hypothalamic dysfunction

- Menstrual cycle changes

- Decrease in bone mineral density

- Bone stress injury

Energy availability directly affects menstrual cycle changes. Energy availability and menstrual cycle changes influence bone health. At one end of the spectrum is optimal health, where there is optimal energy availability, eumenorrhea and optimal bone health. At the other end of the spectrum is the severe presentation of the female athlete triad with low energy availability (this can be with or without an eating disorder), functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and osteoporosis. An athlete's diet and exercise behaviours influence which side of the spectrum they are leading towards.[19]

Please see Figure 1 in: 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: [19]

Male Athlete Triad[edit | edit source]

Recently, research has highlighted that the athlete triad also affects male athletes. The three health issues related in the male athlete triad are[20][21]:

- energy deficiency

- reproductive suppression

- poor bone health

Athletes at Risk of Energy Imbalance Issues[edit | edit source]

- Athletes taking part in aesthetic/leanness sports such as dancing, and gymnastics.

- Weight-class sports require an athlete to be a specific weight to compete, such as boxing, wrestling, and mixed martial arts.

- Gravitational sports where weighing less is an advantage for success such as cycling.

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)[edit | edit source]

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) is a relatively new syndrome, first introduced in 2014 by the International Olympic Committee.[23] It reflects an evolution of the female athlete triad concept. Similar to the female athlete triad, energy availability is the underlying cause of RED-S. Low energy availability negatively influences physiological processes and athlete performance. The RED-S concept includes the female athlete triad and it acknowledges that men may also be affected by low energy availability.

Definition of RED-S:

"impaired physiological functioning caused by relative energy deficiency, and includes but is not limited to impairments on metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis and cardiovascular health"[23]

Low Energy Availability (LEA)[edit | edit source]

With low energy availability, there is a discrepancy and inconsistency between an athlete's energy intake (nutrition) and energy expenditure during exercise. This results in the athlete having inadequate energy to support functions needed by the body to maintain optimal health and performance.[24] Low energy availability may be intentional or unintentional. It is important to recognise which form of LEA an athlete may present with as management differs.

- Intentional LEA - athlete intentionally restricts dietary intake to control body weight and/or composition. A complex management plan is necessary with a multidisciplinary team approach (this can include medical, nutritional and mental health support)[25]

- Unintentional LEA - athlete is not meeting the demands of the sport, often during periods of increased training or taking part in sports with high energy expenditure. Management may be easier in that athlete education on the nutritional demands of their training load may be sufficient to address the LEA.[25]

Health effects of RED-S or LEA[edit | edit source]

Table 1 summarises the health effects of low energy availability[24]:

| System | Effects |

|---|---|

| Endocrine |

|

| Menstrual function |

|

| Bone health |

|

| Metabolic |

|

| Cardiovascular | Studies have reported:

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Immunological |

|

| Psychological |

|

| Growth and Development |

|

| Sleep |

|

Disordered Eating and Eating Disorders[edit | edit source]

- Eating disorder - mental health condition

- Disordered eating - control of food intake, abnormal or incorrect beliefs about what the athlete should be eating

- Higher prevalence of disordered eating and eating disorders in sports that are weight-sensitive (gymnastics, dance, runners, boxing)[24]

- Disordered eating and eating disorders are multifactorial with culture, family, the individual and genetics playing a role.[24]

- Risk and trigger factors related to eating disorders include[24]:

- performance pressure

- sudden increase in training volume

- injury

- teammate modelling

- team weigh ins

- relationship with coach - high conflict and low support environment

- Disordered eating is influenced by[24]:

- perfectionism

- competitiveness

- pain tolerance

- perceived performance advantage of weight loss

Performance Implications of RED-S[edit | edit source]

| Performance Implications of RED-S |

|---|

|

Screening for RED-S and Female Athlete Triad[edit | edit source]

Menstrual issues

- Menstruation is a vital sign

- Investigate this in pre-participation screenings and any female athlete who presents for care[26]

- Screen for primary and secondary amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea and oligomenorrhea

- Remember, amenorrhea may indicate energy deficiency, may lead to osteoporosis and bone stress injuries. It may also be an indication that the athlete has an eating disorder.

- Screen for the use of contraceptive medication that may affect menstrual cycles

| Triad Concensus Panel Screening Questions[18] |

|---|

| Have you ever had a menstrual period? |

| How old were you when you had your first menstrual period? |

| When was your most recent menstrual period? |

| How many periods have you had in the past 12 months? |

| Are you presently taking any female hormones (oestrogen, progesterone, birth control pills)? |

| Do you worry about your weight? |

| Are you trying to or has anyone recommended that you gain or lose weight? |

| Are you on a special diet or do you avoid certain types of food or food groups? |

| Have you ever had an eating disorder? |

| Have you ever had a stress fracture? |

| Have you ever been told you have low bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis)? |

Nutritional Intake Problems

Common mistakes that athletes make include:

- decreasing overall intake

- increase in high fibre/high protein foods

- cutting out particular types or categories of food

- Screening questions:

- Are foods being enjoyed for pleasure?

- Is time set our each day for appropriate fuelling?

- Is there variety in food intake?

- Is there awareness of hunger signals?

- Is there an awareness of fullness?

Body weight

Screen for[5]:

- rapid decrease in body weight

- loss of more than 10 percent of body weight in 3 months

- loss of more than 5 percent of body weight in 1 month

- low percentage body fat

- less than 12 percent body fat in females

- less than 7 percent body fat in males

- expected weight and growth curves in paediatric and adolescent athletes

- body weight can be used as an estimate of low energy availability (LEA)

- BMI drops below 17. 5

- drop of body weight below 85% of their body weight

- greater than 10 percent loss of body weight in one month

Training changes

- understand an athlete's normal/usual training routine

- current training regime

- any increases in:

- duration

- intensity

- competitions

- frequency

Cultural and Social Determinants

- periods of fasting

- food culture

- food insecurity

- financial insecurity

Risk Assessment Tools[edit | edit source]

- Female Athlete Triad Cumulative Risk Assessment[19]

- Modified female athlete triad cumulative risk assessment for males

- RED-S Clinical Assessment Tool (RED-S CAT)[27]

- Low Energy Availability in Females Questionnaire (LEAF-Q)

Video on Updated Screening and Prevention of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport[28]

Prevention of RED-S[edit | edit source]

- Education and increased awareness are necessary among athletes and healthcare professionals, coaches, trainers, and managers[24]

- Female athletes have this notion that it is "normal" to have irregular menstrual cycles

- Peer-led support and educational programmes show promise and should be further developed. Recommendations are that these programmes[24]:

- are gender-specific

- involve family/partners

- target athletes, coaches and non-athletes

- Involvement of inter- or multidisciplinary team to support athletes

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lee HS. Why should we be concerned about early menarche?. Clinical and experimental pediatrics. 2021 Jan;64(1):26.

- ↑ Howard SR. Interpretation of reproductive hormones before, during and after the pubertal transition—Identifying health and disordered puberty. Clinical Endocrinology. 2021 Nov;95(5):702-15.

- ↑ Kota AS, Ejaz S. Precocious puberty. InStatPearls [internet] 2022 Jul 4. StatPearls publishing.

- ↑ Lacroix AE, Gondal H, Shumway KR, Langaker MD. Physiology, menarche. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 Mar 17. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Bell, J. Female Athlete Triad and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport. Plus, Course. 2023.

- ↑ Critchley HO, Maybin JA, Armstrong GM, Williams AR. Physiology of the endometrium and regulation of menstruation. Physiological reviews. 2020 Apr 29.

- ↑ Zero to Finals. Understanding the Menstrual Cycle. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Lt9I5LrWZw[last accessed 25/04/2023]

- ↑ Riaz Y, Parekh U. Oligomenorrhea. InStatPearls [Internet] 2021 Dec 28. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Gasner A, Rehman A. Primary Amenorrhea. InStatPearls [Internet] 2021 Sep 8. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Gibson ME, Fleming N, Zuijdwijk C, Dumont T. Where have the periods gone? The evaluation and management of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology. 2020 Jan;12(Suppl 1):18.

- ↑ Ulin M, Ali M, Chaudhry ZT, Al-Hendy A, Yang Q. Uterine fibroids in menopause and perimenopause. Menopause (New York, NY). 2020 Feb;27(2):238.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Talaulikar V. Menopause transition: Physiology and symptoms. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2022 Mar 16.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ambikairajah A, Walsh E, Cherbuin N. A review of menopause nomenclature. Reproductive health. 2022 Dec;19(1):1-5.

- ↑ Hyvärinen M, Juppi HK, Taskinen S, Karppinen JE, Karvinen S, Tammelin TH, Kovanen V, Aukee P, Kujala UM, Rantalainen T, Sipilä S. Metabolic health, menopause, and physical activity—a 4-year follow-up study. International Journal of Obesity. 2022 Mar;46(3):544-54.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Davis SR, Baber RJ. Treating menopause—MHT and beyond. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2022 Aug;18(8):490-502.

- ↑ National Institute of Aging. What is Menopause? Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=af-356SbCkY [last accessed 28/4/2023]

- ↑ National Institute of Aging. What are the Signs and Symptoms of Menopause? Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nMdn6EI6WA [last accessed 28/04/2023]

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Joy E, De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Misra M, Williams NI, Mallinson RJ, Gibbs JC, Olmsted M, Goolsby M, Matheson G, Barrack M. 2014 female athlete triad coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad. Current sports medicine reports. 2014 Jul 1;13(4):219-32.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, Misra M, Williams NI, Mallinson RJ, Gibbs JC, Olmsted M, Goolsby M, Matheson G, Panel E. 2014 female athlete triad coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Feb 1;48(4):289-.

- ↑ Nattiv A, De Souza MJ, Koltun KJ, Misra M, Kussman A, Williams NI, Barrack MT, Kraus E, Joy E, Fredericson M. The male athlete triad—a consensus statement from the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part 1: Definition and Scientific Basis. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):335-48.

- ↑ Fredericson M, Kussman A, Misra M, Barrack MT, De Souza MJ, Kraus E, Koltun KJ, Williams NI, Joy E, Nattiv A. The Male Athlete Triad—A Consensus Statement From the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part II: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return-To-Play. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):349-66.

- ↑ Vivo Phys - Evan Matthews. Female Athlete Triad and Male Athlete Triad. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93yJMK52Nyc [last accessed 28/04/2023]

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, Meyer N, Sherman R, Steffen K, Budgett R, Ljungqvist A. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the female athlete triad—relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Apr 1;48(7):491-7.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Ackerman KE, Blauwet C, Constantini N, Lebrun C, Lundy B, Melin A, Meyer N, Sherman R. International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism. 2018 Jul 1;28(4):316-31.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Torres-McGehee TM, Emerson DM, Pritchett K, Moore EM, Smith AB, Uriegas NA. Energy availability with or without eating disorder risk in collegiate female athletes and performing artists. Journal of athletic training. 2021 Sep 1;56(9):993-1002.

- ↑ Warrick A, Faustin M, Waite B. Comparison of female athlete Triad (Triad) and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): A review of low energy availability, multidisciplinary awareness, screening tools and education. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports. 2020 Dec;8:373-84.

- ↑ Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, Meyer N, Sherman R, Steffen K, Budgett R, Ljungqvist A. The IOC relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool (RED-S CAT). British journal of sports medicine. 2015 Apr 14.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:9