The Role of the Physiotherapist in Learning Disabilities

Welcome to Contemporary and Emerging Issues in Physiotherapy Practice. This page is being developed by participants of a project to populate the Spinal Cord Injury section of Physiopedia.

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Catherine Speirs, Ting Hui Tan, Idris Al Balushi, Kerry Morris, Ioannis Dimitrios Valmas, Nicola carter, Rucha Gadgil, Kim Jackson, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Chee Wee Tan, Shaimaa Eldib, Ines Musabyemariya, Michelle Lee and WikiSysop

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

We are a group of 4th year BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy students at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. As part of our Contemporary and Emerging Issues in Physiotherapy Practice module, we have decided to complete an online learning resource. This resource is primarily aimed at senior physiotherapy students and newly qualified physiotherapists. This online wiki will explore the areas of communication and health literacy when working with patients who have learning disabilities. This resource will take approximately 10 hours to complete and will contribute to your CPD profile. Besides providing you with new information and researched evidence, there will be quizzes and opportunities for you to reflect.

In 2015, there were 27,218 adults with learning disabilities known to local authorities in Scotland[1]. Most people with learning disabilities have greater health needs than the general population. People with learning disabilities are more likely to experience mental illness and are more prone to chronic illnesses such as epilepsy, physical and sensory impairments. A systematic review carried out in the Netherlands discovered that people with learning disabilities are at an increased risk of fractures and musculoskeletal impairments[2]. 50-90% of people with learning disabilities also have communication difficulties[3].

Aims[edit | edit source]

The aims of this wiki are:

- To provide final year physiotherapy students and new graduates with an online learning resource which develops their knowledge of learning disabilities and the common associated conditions that may require physiotherapy interventions.

- To introduce final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified graduates to the skills and strategies which can be utilised within their practice to offer a more effective and comprehensive management of communication and health literacy to those with learning disabilities.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

By the end of this online activity you should be able to:

- Discuss the impact of learning disabilities on the person and their needs in relation to physiotherapy interventions.

- Critically appraise the evidence base and some of the key approaches surrounding communication and health literacy within learning disabilities.

- Summarise the characteristics of psychological impacts and the underlying neurophysiology of communication difficulties experienced by those with learning disabilities.

- Critically reflect upon the possible challenges faced by physiotherapists when communicating with people who have learning disabilities.

- Critically evaluate the role of the physiotherapist in the area of learning disabilities with reference to relevant literature.

- Formulate stronger patient-therapist relationship by applying these effective communication methods in the practice setting.

Learning styles[edit | edit source]

Different individuals have different learning styles, thus as part of our consideration for you to make the most of your learning through this wiki, various activities and resources will be included to cover the different learning types and styles.

Are you aware of the different learning styles and which best suits you?

If you are not aware of your ideal learning style but would be interested in finding out, you can fill in a short questionnaire here, which will take approximately 5 minutes. This will then reveal your ideal learning style and most suited learning methods, which would be useful to know, not only throughout this wiki, but also as part of your future learning.

The different learning styles are:

- Visual

- Aural/Auditory

- Read/write

- Kinesthetic

- Multimodality

Blooms Taxonomy[edit | edit source]

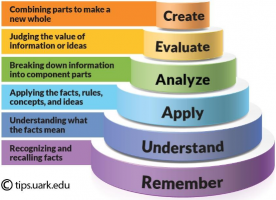

Blooms taxonomy uses a hierarchy to establish the different learning levels. Figure 1 demonstrates the pyramid structure and highlights that a foundation needs to be part of the learning process before this learning can be applied to everyday practices, and evaluations can be made.

Learning outcomes for this wiki have been based around Bloom's model, and the higher learning levels have been selected to be appropriate for final year students and newly qualified physiotherapists. This is to allow a deeper understanding of the topics covered and to be able to apply these to everyday situations.

Why is there a need for this Physiopedia page[edit | edit source]

- There is a gap in the literature.

- There is no current module in the BSc/MSc pre-reg courses on learning disabilities.

- Literacy and communication difficulties are experienced by many people with learning disabilities.

Activities Provided[edit | edit source]

There will be different activities provided throughout this resource which are aimed at the different learning types.

How this resource relates to the Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF)[edit | edit source]

The KSF is a competence framework that supports professional development and career progression for professionals working in the NHS. It ensures that staff are supported so that they can carry out their job effectively.This physiopedia page aims to address some of the core components of the KSF required of a Band 5 Physiotherapist. By completing this online resource it will help you to achieve some of the key indicators.

Here is a list of the key indicators that you will achieve in this wiki:

Communication:

- Improves the effectiveness of communication through communication skills.

- Constructively manages barriers to effective communication.

Personal and people development:

- Takes responsibility for own personal development and takes an active part in learning opportunities.

- Evaluates the effectiveness of learning opportunities and alerts others to benefits and problems.

Quality:

- Acts consistently with legislation, policies, procedures and other quality approaches and encourages others to do so.

- Uses and maintains resources efficiently and effectively and encourages others to do so.

Equality and diversity:

- Recognises people’s rights and acts in accordance with legislation, policies and procedures.

- Acts in ways that:

- Respect diversity.

- View people as individuals.

Assessment and treatment planning:

- Selects appropriate assessment approaches, methods, techniques and equipment, in line with

- Individual needs and characteristics.

- Evidence of effectiveness.

- The resources available.

- Monitors individuals during assessments and takes the appropriate action in relation to any significant changes or possible risks.

- Evaluates assessment findings/results and takes appropriate action when there are issues.

- identifies individuals whose needs fall outside protocols / pathways / models and makes referrals to the appropriate practitioners with the necessary degree of urgency.

Understanding learning disabilities

[edit | edit source]

Prior to beginning this online resource, please take a moment to ask yourself these questions:

(TO INSERT REFLECTION HERE)

Also, please take a moment to reflect on your current knowledge and experience:

(TO INSERT TEST YOURSELF HERE)

Definition and diagnostic criteria for learning disabilities[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defined a learning disability as ‘‘a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is especially characterized by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e., cognitive, language, motor, and social abilities’’ (WHO 1992). However, this definition is outdated and implied the term ‘mental retardation’ which is deemed very offensive by many people today.

The current definition of a learning disability is defined by Valuing People, the 2001 White Paper report on the health and social care of people with learning disabilities.

“A learning disability includes the presence of:

- a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), with;

- a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning);

- which started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development.”

The terms used to describe a person with a learning disability has been changing since the 1970s, from people with mental sub-normality to mental handicap to eventually learning disability in the 1990s. In other countries such as the United States (US), the terms ‘intellectual disability’ and ‘mental retardation’ are used instead. Do note that in the US, the term learning disability is used to describe specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia, dyspraxia and dyscalculia.

Internationally, three criteria have to be met before a learning disability can be identified or diagnosed:

- Intellectual impairment (IQ<70);

- Social or adaptive dysfunction combined with IQ; and

- Early onset.

Watch the video below to know more about the meaning of learning disabilities:

Learning disability VS learning difficulty[edit | edit source]

Learning Disability ≠ Learning Difficulty

As mentioned earlier, different terminologies are used in different countries. It is important not to confuse learning disability with learning difficulty. In the UK, specific learning difficulties refers to conditions such as dyslexia, dyspraxia/developmental coordination disorder, dyscalculia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Specific learning difficulties affect the way information is learned and processed. It is a neurological condition rather than a psychological condition and it does not affect intelligence. A student may be diagnosed with a learning difficulty if there is a big gap between achievement and ability or there is lack of achievement for age and ability. Dyslexia is a difficulty that affects 10% of the population. Dyslexia affects the way a person processes information, they may have difficulty with memory, organisation and sequencing. Dyspraxia is a disorder that affects fine and gross motor skills in children and adults. Dyscalculia is a difficulty understanding maths concepts and symbols. Finally, ADHD is a disorder that affects attention. A person with ADHD may be restless, inattentive, impulsive, erratic and have inappropriate, unpredictable behaviour. They may appear unintentionally aggressive.

Prevalence and demographics of learning disabilities [edit | edit source]

Global: Higher prevalence for developing countries, women, and children from poorer households and ethnic minority groups, but specific data are difficult to secure. One-fifth of the estimated global total population (110-190 million people) experience significant disabilities. Globally, one in 160 children has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). 1991 prevalence estimates for children seven to ten years old are that two in 1000 children are identified with cerebral palsy and four in 1000 with moderate to profound intellectual disability (IQ<50).

https://www.healthandenvironment.org/what-we-know/health-diseases-and-disabilities/learning-and-developmental-disabilities-research-and-resources

Europe: In the European Union (15 countries) 1.1 to 1.5 million people have a severe learning disabilities and 2.3 to 2.7 million people have a mild learning disability. http://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Intellectual-Disability-in-Europe.pdf

United Kingdom: 1.5 million people in the UK are thought to have a learning disability (Foundation for people with learning disabilities, 2016)

England: In 2011, it was estimated that there were 1,191,000 people have learning disabilities. This includes 905,00 adults with learning disabilities, of whom, 189,000 were known to learning disability services (Emerson et al. 2011).

Scotland: In 2015 the Scottish Commission for Learning Disabilities (SCLD) reported the number of people with learning disabilities in Scotland. Collection of Learning Disabilities Statistics Scotland data was carried out by the ScotXed Team within the Scottish Government. This aimed to increase standardisation and improve the quality of the data. In 2015, there were 27,218 adults with learning disabilities known to local authorities. This equates to 6.1 people with learning disabilities per 1,000 adults in the general population. 4,617 adults were identified as being on the autism spectrum. 70% of these adults had a learning disability (SCLD, 2015).The images below represent the number of adults known to each local authority and the proportion of adults known to the NHS boards.

(TO INSERT 2 STATISTIC CHARTS HERE)

Different levels of learning disability[edit | edit source]

(TO INSERT LEVELS OF LEARNING DISABILITY HERE)

The term ‘learning disability’ is a very broad description for this group of individuals, with the threshold set at an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) of below 70 in the United Kingdom (UK). As such, terms such as profound, severe, moderate and mild are used in the UK to describe the different severity and levels of need which these individuals may have.

Profound: Individuals with an IQ score under 20, with severely limited understanding. They have difficulty communicating, require support with mobility and may need support with their behaviour. They may have multiple disabilities such as visual impairments, hearing impairments and difficulty with movement. They may also have extensive health needs, epilepsy and autism.

Severe: Individuals with an IQ score of 20-35. They often use basic words and gestures to communicate their needs. They may need a high level of support with activities of daily living. Some may have additional medical needs and require more support with mobility.

Moderate: Individuals with an IQ score of 35-50. They are able to communicate their day-to-day needs and wishes. They may need some assistance and guidance with their personal care and may require longer time to learn new skills.

Mild: Individuals with an IQ score of 50-70. They are able to hold a conversation and communicate their needs effectively. They are often independent in caring for themselves and have basic reading and writing skills. They may require support to understand complex ideas.

Factors resulting in learning disability[edit | edit source]

According to the British Institute for Learning Disabilities (2011), these are key factors of learning disability:

Chromosomal conditions: Chromosomes make up the genetic blueprint for humans. Everyone has 46 chromosomes in their cells. Abnormality in their chromosomes can result in a learning disability. Such conditions include Down’s Syndrome, Fragile-X syndrome, Williams Syndrome, Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome and Prader-Willi Syndrome.

Maternal factors: Infections such as Cytomegalovirus and Toxoplasmosis, factors such as diet deficiencies and excessive alcohol consumption during pregnancy can cause learning disability in the unborn child.

Metabolic disorders: A person’s metabolism controls all the chemical reactions in the body. Certain conditions affecting metabolism can result in a learning disability. For example, Phenylketonuria is a disorder that increases the levels of a substance called Phenylalanine in the blood. Phenylalanine is an amino acid which is normally obtained through the diet. If untreated the abnormally high levels of phenylalanine can cause severe learning disabilities.

Events during birth: A learning disability can occur if a baby’s oxygen supply is disrupted during labour, if a child is born extremely premature or becomes very ill after birth.

Events after birth: Some childhood infections such as encephalitis and meningitis can cause learning disabilities. A severe head injury can also cause a learning disability.

Common associated conditions[edit | edit source]

For the purpose of this online learning resource, Down’s Syndrome, Autism and Cerebral Palsy will be explored.

Down’s Syndrome

Down’s Syndrome occurs when there are three copies of chromosome 21 in the cells of the body. This is also known as trisomy 21. Having three copies of chromosome 21 disrupts the normal course of development and causes the characteristics of Down’s Syndrome and the associated health risks. Strong associations have been found between maternal socioeconomic status, maternal age and chromosome 21-nondisjunction, the cause of 95% of Down syndrome cases. There are three types of Down Syndrome: Trisomy 21 (95%), Translocation (4%) and Mosaic (1%). It is said that 750 babies are born with Down’s Syndrome each year in the UK. People with Down’s syndrome have distinct facial features such as a flat face, a small broad nose, upward slanting eyes and a large tongue, as well as common physical traits of low muscle tone, small stature and a single deep crease across the center of the palm. People with Down’s Syndrome have a higher risk of developing respiratory conditions, leukemia, heart defects, gastrointestinal obstruction, hearing loss and eye abnormalities. People with Down’s syndrome can have a moderate to severe learning disability and often develop much slower than their peers. They may also face communication difficulties, for example stuttering (Jackson et al 2014), which will be explored in later parts of the wiki.

https://www.healthandenvironment.org/what-we-know/health-diseases-and-disabilities/learning-and-developmental-disabilities-research-and-resources

Here is a video describing Down’s syndrome:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ze_6VWwLtOE

Autism

Autism is a lifelong developmental disability. In the UK, it affects 700,000 people, that is more than 1 in a 100. It is known as a spectrum condition as it affects people differently and to varying degrees. Some people with autism will lead independent lives while others will need lifelong support. Some people have a learning disability (44%-55%) while others have average to above average intelligence. Some people also have mental health issues and other health conditions.

People with autism report that the world is a very overwhelming place for them. They find it difficult to understand and relate to other people. This makes it difficult for them to take part in everyday activities and social situations. It is a condition that cannot be cured. Autism is defined as affecting social communication and social interaction.

Social communication

People with autism have difficulties with interpreting verbal and non-verbal language, tone of voice and gestures. They have a literal understanding of language. They may find it difficult to understand facial expressions and jokes and sarcasm. Some people with autism may not speak while others may have limited speech. They may use alternate methods of communication such as sign language and symbols.

Social interaction

This means that people with autism have difficulty ‘reading’ other people. They may appear insensitive, not seek comfort from other people, prefer time alone when overloaded by other people and appear to behave strangely. It may be hard for people with autism to make friends.

People with autism may also have repetitive behaviours and specific routines. As the world is an unpredictable place for autistic people they tend to have a daily routine so they know what they are going to do every day. For example, they may want to travel to school/work the same way every day or eat the same meal for breakfast every day. Some autistic people have a highly-focused interest which starts from an early age. These can change or be lifelong. Some examples include, music computer games, train, movie or books. Finally, some people with autism may be hyper- or hypo-sensitive to sound, taste, touch, smells, lights, colours, pain or temperature. This can cause anxiety or on the other hand they may be fascinated by certain lights or colours.

This short video illustrates the world from the view of a person with autism. Can you make it to the end? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lr4_dOorquQ

Here are two videos describing autism and the impact it has on individuals:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_HGUyk5U_j8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d4G0HTIUBlI

Cerebral Palsy

The Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (Cans 2000) defines cerebral palsy (CP) as:

“A group of permanent and non-progressive disorders of movement and posture caused by a central nervous lesion, damage or dysfunction originating early in life.”

CP is thought to occur in 2 to 3 per 1000 live births (Teckin 2015). It is an incurable neurological condition that is caused by trauma to the brain or complications that occur before, during or shortly after birth. CP primarily affects mobility and coordination, but may cause intellectual disabilities in severe cases, as well as an inability to speak. Severe cases are usually diagnosed by the age of two, while milder manifestations may not be diagnosed until a child is 5 years old.

Most symptoms of CP, such as impairments to cognition, speech and movement, are difficult to recognise until a child is of age to learn how to speak and walk. Other common symptoms include seizures, and impaired bladder and bowel control. Learning disabilities in CP patients can be complicated by the fact that CP symptoms include vision, hearing and communication impairments, which can make it difficult for them to express themselves and for others to know whether the patient comprehends the information.

Early intervention before a child turns 3 can help with the learning disabilities associated with the condition.

http://www.unitednationalcerebralpalsylawyer.com/education/learning/

Evidence has shown that 2% of the CP population has learning disability and the number is steadily increasing (Xenitidis K et al 2000). This may be due to higher survival rate in preterm babies, thus CP and learning disability are more highly represented (Aspray TJ et al. 1999). This is supported by Colvin et al. 2004, where evidence showed that babies of 20-32 week gestation have significantly higher risk of both cerebral palsy and learning disability. A systematic review carried out by Odding et al. (2009) revealed that 23-44% of the CP population have a cognitive impairment and 30-41% with a severe impairment (IQ<50).

http://www.essay.uk.com/free-essays/medicine/cerebral-palsy-nursing.php

There are four types of CP, each differently defined based on their symptoms:

- Spastic CP: The most prevalent form, accounting for 70-80% of the cases, and are caused by complications in brain-to-nerve-to-muscle communication. These patients are hypertonic and have stiff, jerky movements. They may also develop joint contractures and deformities.

- Dyskinetic CP: This accounts for 25% of the cases and is caused by damage to the basal ganglia. These patients have slow, involuntary, purposeless movements.

- Ataxic CP: This accounts for 5-10% of the cases and is caused by damage to the cerebellum. These patients usually have all 4 limbs and trunk affected, and are hypotonic with poor balance and coordination, and intention tremor.

- Mixed CP: This accounts for 10% of the cases, and is a combination of 2 or more types of CP. These patients usually have stiff and involuntary movements, and low muscle tone, caused by injury to both the pyramidal and extrapyramidal areas of the brain.

http://www.cerebralpalsysource.com/Types_of_CP/index.html

Impact of learning disability on the person and physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

There is a wide spectrum of orthopaedic problems with learning disability, some as a result of the underlying condition and some others due to accidents.

Individuals with learning disability (LD) are exposed to higher risk of injuries more than the general population. It has been shown in Denmark, US and Australia that adults with learning disability are at higher risk of death compared to general public (Janet F. et al 2014). These include deaths from accidents, falls, burns, drug toxicity and choking (Durvasula., 2002). Finlyson et al (2014) carried out a study to investigate injuries in 511 adults affected by LD in the UK for 12 months and the result showed that they were twice likely to get injured more than others; with falls found to be the most common reason of injury (accounting 55% of all injuries).

In addition, people affected by learning disability are slower in learning certain skills than others and therefore need more assistance in several aspects of their lives. This is influenced by the severity of the disability which varies from mild to profound (FB foundation website).

Researches have indicated the increased prevalence of psychiatric disorders among people with learning disabilities compared to general population. According to WHO, the prevalence of psychiatric and behavioural disorders is at least three times greater in learning disability individuals in comparison to unaffected population (Rennie J., 2007). These disorders include:

- Affective (mood) disorders: depressive episodes, recurrent depressive disorder, cyclothymia, manic episodes, bipolar affective disorders and persistent mood disorder.

- Anxiety, stress related disorders: phobic anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders.

- Stress related disorders: The people affected with learning disability are more vulnerable to physical, sexual and emotional abuse, therefore more likely to complain of stress-related disorders.

- Personality disorders: The prevalence of diagnosed personality disorders in learning disability individuals has varied from 22% to 92%, showing that majority of the learning disability population are presenting with personality disorders such as paranoia, schizoid, antisocial, anxious and dependent personality disorders.

- Dementia: The prevalence of people with Down Syndrome is in the same level as the general population over the age of 65 but in Down Syndrome, dementia appears in earlier age. This explains the impact of learning disability on occurrence of dementia (Rennie J., 2007).

Health risks of people with learning disabilities:

- Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of death in people with learning disabilities (14-20%).

- Respiratory disease is much higher in people with learning disabilities and is thought to be leading cause of death (46%-52%).

- The prevalence of dementia is much higher in people with learning disabilities compared to the general population.

- Epilepsy is thought to be 20 times higher in people with learning disabilities. Uncontrolled epilepsy can have a negative effect on a person’s quality of life and mortality.

- Sensory impairments: people with learning disabilities are 8-200 times more likely to have a vision impairment and 40% are reported to have a hearing impairment compared to the general population.

- Physical impairments: Adults who are non-mobile have an increased mortality rate than if they were mobile. A study in the Netherlands reported that people with learning disabilities are 14 times more likely to have a musculoskeletal condition.

- People with learning disabilities are also at an increased risk of oral health problems, dysphagia, diabetes, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, constipation and endocrine disorders (Emerson and Baines 2010).

- People with learning disabilities have personal health risks such as:

- Less than 10% of adults in supported living eat a balanced diet.

- >80% of adults with learning disabilities engage in levels of physical activity below the Department of Healths minimum recommendation.

- People with learning disabilities are more likely to be either underweight or overweight/obese (Emerson and Baines 2010).

Obstacles within health system[edit | edit source]

People with learning disabilities have poorer health than people without disabilities, and to an extent, this is avoidable. People with learning disabilities face inequalities from early life, and this includes barriers in accessing timely, appropriate and effective health care.

People with learning disabilities have shorter life expectancy and an increased risk of early death compared to the general population. The causes of mortality in people with moderate to severe learning disabilities is three times higher than the general population (Tyrer and McGrother 2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19694898

A range of organisational barriers to accessing healthcare services have been identified, these include:

- Lack of services.

- Physical barriers.

- Failure by healthcare professional to make adjustments for people with regard to literacy and communication difficulties.

- ‘Diagnostic overshadowing’ – where symptoms of physical ill health are mistaken or attributed to a person’s behavioural problem.

- Negative attitude of healthcare staff towards people with learning disabilities (Emerson and Baines 2010).

(TO INSERT QUIZ HERE)

Role of the physiotherapist

[edit | edit source]

Introduction to the role[edit | edit source]

Mainstream or specialist physiotherapy services[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy assessment[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

24-hour postural care[edit | edit source]

Falls prevention[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity promotion[edit | edit source]

Education[edit | edit source]

Reflection[edit | edit source]

Communication

[edit | edit source]

Definition of communication[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier, 50 to 90% of the people with learning difficulties have communication difficulties (Chadwick & Jolliffe, 2009, Veselinova, 2012, and Jackson et al., 2014). According to Chadwick and Jolliffe in 2009, communication is defined as “a mutual interactive process involving adaptation by both the communicative partners”. It is not just a pure transaction of information, but also relationships can be formed and build up in the process (Higgs et al., 2009).

Language is a complex form of communication that involves written or spoken words to convey ideas and symbolise objects. Reading, writing, drawing, speaking, listening, adjusting one’s tone of voice, making eye contact are all involved on communication. Communication involves ‘expression’ and ‘comprehension’ with each aspect being related to a specific neural network.

Physiology of brain and how it affects communication[edit | edit source]

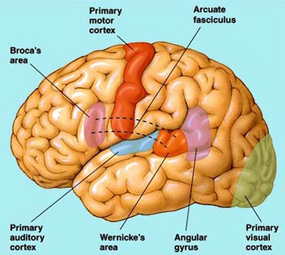

The language centres are located in the left hemisphere in approximately 95% of human beings. Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area are located in the left hemisphere of the brain.

Broca’s area is known as the motor-speech area and it is located adjacent to the precentral gyrus of the motor cortex in the frontal lobes. This area controls the movements required for articulation, facial expression and phonation.

Wernicke’s area includes the auditory comprehension centre. It lies in the posterior superior temporal lobe near the auditory cortex. It plays a role in understanding both spoken and written messages as well as being able to formulate coherent speech. Commands generated in Wernicke’s area are transferred via a fibre tract called the arcuate fasciculus to Broca’s area. Wernicke’s area receives input from both the visual cortex and the auditory cortex.

Types of communication difficulties[edit | edit source]

Aphasia

Damage to the language centres of the brain can result in aphasia. Aphasia can affect expression and comprehension of speech, reading and writing, gesture and the use of language. There are 3 types of aphasia - expressive, receptive and global.

- Expressive aphasia is when a person has difficulty translating their ideas into meaningful sounds which results in non-fluent speech. It is associated with damage in Broca’s area.

- Receptive aphasia is associated with damage in Wernicke’s area. People with receptive aphasia have difficulty in the comprehension of language.

- Global aphasia occurs where there is widespread brain damage including lesions in the left hemisphere. This results in impairment of both expressive and receptive language functions. There are also a range of other neurological signs such as hemianopia, hemiplegia, visual impairments, auditory impairments, attention and memory impairments and other cognitive impairments.

Dysarthria

Dysarthria refers to difficulty with executing speech. There are five sub-systems that are required in the coordination of speech. These include respiration, phonation, articulation, resonance and prosody. Weakness in any of these systems or incoordination of these systems can cause dysarthria.

Apraxia of Speech

This is an inability to programme speech movements. It is an impairment in the ability to coordinate the timing, force production and sequencing of movements for the production of speech.

Comprehension impairments

- A person may not understand some or all of the instructions that are given to them.

- A person’s non-verbal communication may suggest that they understand what you are saying but in fact they may not understand what you are saying. A person may mirror you, such that if you smile and nod they may do the same and they may also mirror your body language too.

Expressive impairments

Some people may have difficulty finding their words which will affect the way they answer your questions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IyV1v-nib38

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hp4PW17U_h8

Impact of communication difficulties[edit | edit source]

Difficulty in communication can lower one’s self-esteem and result in low moods which will further impair communication (Jackson et al., 2014). This may result in “diagnostic overshadowing”, where people with learning disabilities are often misunderstood as having challenging behaviour when it is in fact their way of trying to communicate (Kingston & Bailey, 2009), and hence they are less likely to have chances to express their views (Lewer & Harding, 2013).

Barriers to communication[edit | edit source]

People with learning disability have limited vocabulary (Godsell & Scarborough, 2006, and Sperotto, 2016), problems expressing themselves (Godsell & Scarborough, 2006, and Chadwick & Jolliffe, 2009) and comprehending verbal and written information (Chadwick & Jolliffe, 2009). They may also feel apprehensive and stressed meeting strangers in new environments.

Types of barriers:

http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/business-communication/4-different-types-of-barriers-to-effective-communication/1004/ http://managementstudyguide.com/communication_barriers.htm#

http://www.skillsyouneed.com/ips/barriers-communication.html

Language/Cultural/Perceptual Differences

- Different languages/tongues

- Unfamiliar accents

- Use of jargon

- Multiple meanings of a word - easy to misinterpret

Psychological/Emotional

- Difficulty expressing emotions

- Low self-esteem

- Personal taboo topics

- Poor mood - less receptive to communication

Physical disabilities

- Hearing problems

- Speech difficulties

- Visual problems

- Limited memory space - information overload, poor retention of information

Attitudinal

- Inattention

- Resistance to change

- Lack of motivation

- Unwilling to communicate

Distractions

- Louds noises

- Bright lightings

- Crowded area

Strategies/methods/tools for effective communication[edit | edit source]

When speaking to people with learning disabilities, easy and simplified language should be used at a slow comfortable pace to promote positive interactions, but it should not appear supercilious (Veselinova, 2012).

Common subtle indicators of pain you can watch out for include changes in behaviour, noise level, body language or facial expressions and holding the part of the body that hurts (Beacroft & Dodd, 2011).

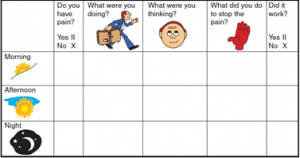

In 2009, Kingston and Bailey recommended tools such as the “pain diary” (Figure 1), which is “a tick chart designed for the person with a learning disability to complete”, as well as the “pain story” (Figure 2), which is “a templated designed to help individuals talk about their pain” and “included aspects of a person’s history, their previous experiences of pain, and the current influences upon their behaviour”. These simple tools with pictures and symbols have been found to enhance communication and assessment, as they not only “help with identifying the location, type, severity and duration of pain” (Beacroft & Dodd, 2011), but also allowed people with learning disabilities the opportunity and freedom to talk and describe their pain, and it is highly reassuring for them when the health professionals like physiotherapists are able to understand and believe their words (Kingston & Bailey, 2009).

For those with more complex communication difficulties, there are “augmentative and alternative communication strategies (AACs)” (Godsell & Scarborough, 2006) that physiotherapists can use, such as “Makaton, British sign language, braille and the use of assistive technology” (Veselinova, 2012). Makaton is a language programme that uses signs and symbols to help people communicate (Let’s Talk Makaton, 2016). The signs and symbols are used in spoken word order and help develop the communication skills of the person (Let’s Talk Makaton, 2016). Furthermore, according to the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists in 2006, “manual signing continues to be used as an intervention strategy” for the people with learning disabilities (Chadwick & Jolliffe, 2009), thus if physiotherapists are able to pick up simple signing, it will greatly aid in their communication with their clients with learning disabilities.

Inclusive Communication

Inclusive communication is a means of sharing information so that everybody can understand it. For service providers, it means that you understand that people understand and express themselves in different ways. Inclusive communication refers to:

- Written information

- Face to face

- Telephone

- Online information

Inclusive communication aims to ensure that people with communication support needs are able to live independently, access services easily and are able to participate in the wider community.

A person with communication support needs may need support with understanding, expressing themselves and interacting with others. As physiotherapists we need to use other methods of communication so that our patients understand what we are saying to them and are able to express themselves.

A person with communication support need may:

- Avoid services completely.

- Not turn up for an appointment.

- Respond only to some advice given or nodding their head as though they understand.

- Ask lots of repeated questions.

- Give irrelevant, rambling or unclear sentences.

- Have challenging behaviours.

- Appear bored or unable to maintain attention.

- Have difficulty describing feelings or events, may be explained in sentences that do not make sense.

- Express very strong emotions that may seem inappropriate to the situation such as anger or frustration (The Scottish Government 2011)

- (TO INSERT COMMUNICATION FORUM SCOTLAND DIAGRAM HERE)

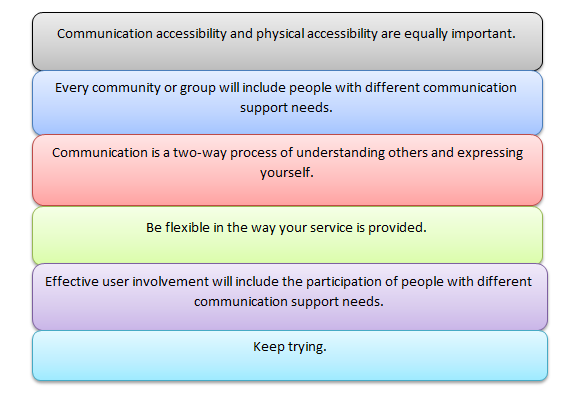

The six principles of inclusive communication are:

Acquiring informed consent[edit | edit source]

It is imperative to always acquire informed consent from the patients before commencing assessments or treatments. Informed consent is defined as: ‘an individual is always presumed to be competent, or to have mental capacity to enter into a particular transaction, until the contrary is proved’ (Law Society – BMA 1995). Therefore, you should bear in mind that no one, even the parents, can consent to or refuse treatment on behalf of another adult who lacks capacity to consent. Some people will never be able to make decisions, but judgement must not be made until all practicable steps have been taken to help the patient. You must only regard a patient as lacking capacity once it is clear that after all appropriate help and support, they cannot understand, retain, use or weigh up the information needed to make that decision, or communicate their wishes.

Therefore, consent can be waived, but only under certain conditions:

- To preserve life, health or well being of the person e.g. in emergency situations

- If the patient is being held under the Mental Health Act

- It is agreed during a formal ‘Best Interests’ meeting (a multidisciplinary meeting including all professionals/ carers/family/patient involved in the care of the patient) that a particular intervention was in accordance with best practice, which includes best medical interests and the patient’s general being, wishes, and needs.

Who can give informed consent? Individuals who received an understandable explanation of the following:

- What will happen and why it is necessary in very simple terms

- The benefits and risks of the treatment and what alternatives are available

- What will happen if the patient does not consent, and

- Being able to retain what you have discussed with them and able to make a decision

Never ever coerce a patient into making decisions, just because you believe that the patient should have the treatment. If controversial circumstances are involved, decisions around best interests should be made via the court.

To find out whether the individual has the capacity to give informed consent, it is essential to:

- Elicit what skills or knowledge the patient may require to exercise capacity

- Find out what support and information the patient requires to achieve capacity, and

- Involve someone who knows the patient well and their level of communication

What does capacity to give informed consent mean?

Capacity refers to the ability to use and understand information to make a particular decision at a particular time, and can vary in the same person for different decisions. Understanding depends on cognitive abilities, effective communication and accessible information. A person with capacity has the right to refuse treatment, whereas in the case of an adult who lacks capacity, the health professional has a duty to provide treatment and care in the best interests of that adult, even if the person does not agree.

Where the patient has never been competent, relatives, carers and friends may be best placed to advise on the patient's needs and preferences. It is good practice to consult with people close to the patient to gain agreement unless the person had good reasons that they would not wish those people to be consulted, or the situation is urgent. If an incompetent patient has clearly indicated in the past, while competent, that they would refuse treatment in certain circumstances (an 'advance refusal'), and those circumstances arise, you must abide by that refusal.

http://www.dvh.nhs.uk/for-patients-and-visitors/learning-disabilities/consent/

http://www.gmc-uk.org/learningdisabilities/237.aspx http://www.intellectualdisability.info/how-to-guides/articles/consent-and-people-with-intellectual-disabilities-the-basics

Someone with severe learning disability is thought to be unable to make a decision if they can't:

- understand information about the decision

- remember that information

- use that information to make a decision

- communicate their decision by talking, using sign language or by any other means

http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Consent-to-treatment/Pages/Capacity.aspx

(TO INSERT QUIZ HERE)

Health literacy

[edit | edit source]

Definition of health literacy[edit | edit source]

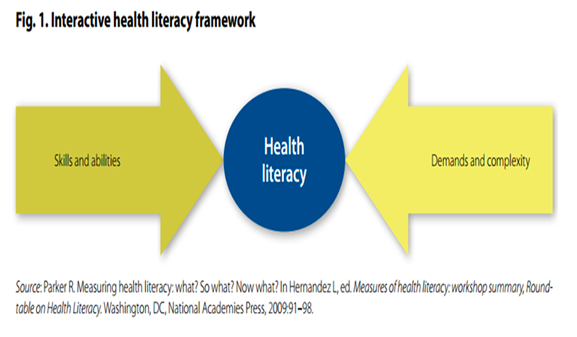

<u</u>Health literacy has many definitions released since the first definition introduced by the Council on Scientific Affairs for the American Medical Association (1). The World Health Organization in collaboration with the European Health Literacy Consortium (2) developed and released the following definition: “Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people’s knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise and apply health information in order to make judgements and take decisions in everyday life concerning health care, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course”.

The European Health Literacy Consortium based their research for the determination of the health literacy terminology on the European Health Literacy Survey. This model was based on the medical and public health views of health literacy and the data were collected through the analysis of 17 peer-reviewed definitions and systematic literature reviews analysis.

It relates to a range of communications including, written, spoken and visual, as identified by NHS (3). As per European Health Literacy Consortium (2) the main purpose of health literacy is “to promote health care through accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health-related information within health care”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lK4FCCMcC1A

The need for health literacy[edit | edit source]

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (4) estimated that 16% of the adult world population, lack even the basic literacy skills.

According to Doyle et al. (5) communicating health information is a core skill required by all healthcare professionals. In order for the information provided to be useful, it is critical that the recipients are able to understand the information they are given.

Part of the difficulties with communication that people with learning disabilities may face include an inability to understand speech, writing and symbols. This will make any situation within healthcare difficult but it especially applies when providing information or giving instructions to patients, noted by Chinn (6).

People working within health and social care usually respond well when patients have poor health literacy. However, as per Scottish Government (7), a patient’s health literacy needs is not always evident and professionals can make false assumptions. NHS (3) recognized that improving people’s understanding is important as when our health literacy needs are not met, the safety, effectiveness and person-centeredness of our care is undermined. The Patient Rights (Scotland) Act (8) states that the needs of patients should be considered, patients should be encouraged to be involved with decision making, and information should be provided in a way that patients can understand. It is suggested that (7, 9):

- Low health literacy has been linked to poor health behaviors and outcomes, independent of other socio-demographic factors.

- Health behaviors and outcomes associated with poor health literacy

- Reduced health-related knowledge

- Poor self-management skills

- Poor communication between healthcare professional and patients leading to reduced involvement when making decisions

- Increased risk of developing comorbidities

- Non-adherence to medication due to difficulty understanding instructions

- Lower self-reported health status

- Find it harder to access appropriate services

- Reduced use of preventive healthcare services

- Increased risk of hospitalization and longer inpatient stays

- Increased healthcare cost

Health literacy in numbers[edit | edit source]

<uWithin Scotland, 26.7% of people have occasional difficulties with day-to-day reading and numeracy, and 3.6% will have severe constraints (7).

Those with intellectual disabilities face a range of challenges with communication; between 50-90% are estimated to have significant difficulties with communicating (6). This makes communication with healthcare professionals difficult and can affect their ability to make informed decisions.

Taking a closer look in (10):

According to the graph more advanced countries like Netherlands have a high percentage of education which affects positively the health literacy numbers compared to other European countries, e.g. Bulgaria, with less educated citizens. The classification of the education of each country is based on the International Standard Classification of Education.

Internationally the statistics about health literacy are higher in countries with better quality of life, e.g. Western countries, reaching up to 97% compared to countries with less or no quality of life, where the percentage of health literacy can drop down to 50% or even less, given in diagram below (11).

National and international actions[edit | edit source]

Techniques and tools/strategies[edit | edit source]

Impact of disability on general population[edit | edit source]

Policies and guidelines

[edit | edit source]

Case study

[edit | edit source]

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Scottish Commission for Learning Disabilities. Learning disability statistics scotland, 2015. SCLD: Glasgow, 2016.fckLRhttp://www.scld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/2015-Learning-Disability-Statistics-Scotland-report-1.pdf (accessed 2 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Jansen DEMC, Krol B, Goothroff W, Post D. People with intellectual disability and their health problems: a review of comparative studies. Journal of intellectual disability research. 2004:48;2;93-102. Available from:http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00483.x/epdf (accessed 18 Jan 2017).

- ↑ Chadwick DD, Jolliffe J. A pilot investigation into the efficacy of a signing training strategy for staff working with adults with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2009,37:1; 34–42.