The Road to Writing and Moving in Early and Middle Childhood

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, Tarina van der Stockt, Wanda van Niekerk and Cindy John-Chu

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Postural control begins in the brain and ends in the hand or foot. Typically, by the age of 7 years, postural control should be consolidated and automatic and children will be “writing ready” and “sport ready”.[1] However, some children may not develop this postural control for a number of reasons, including:[1]

- They may be too floppy or bendy - i.e. they have low connective tissue tone with underlying weaknesses, even if they are sporty. This may be caused by conditions such as:

- Benign joint hypermobility syndrome

- Marfan syndrome

- Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

- The Beighton Scale is used to measure hypermobility[2]

- Lack of practice, which leads to muscle weakness

- An inability to concentrate on one specific activity

- A child’s temperament

- Too shy

- Too nervous

- Gives up easily

- Children who have different brain development, which affects their ability to learn from everyday experiences - i.e. children who do not learn by “doing”

Learning Through Play[edit | edit source]

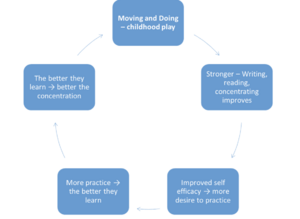

As is shown in Figure 1, children typically experience by “doing” things. The more “doing”, the more learning. The more “doing”, the stronger their muscles get. Strong muscles and exercise are good for writing, reading, concentrating and exercising. Exercise is also good for happiness, health, friendships.

The Building Blocks of Learning[edit | edit source]

Children develop motor competence in their early years (i.e. up until 5 years old). These fundamental motor skills enable children to go onto develop specialised movement and sport skills[3] - these skills have been associated with physical activity both in childhood and adulthood.[4]

Based on the research by Ayres[5] and Stock Kranowitz,[6] early learning can be broken down into four levels:[1]

Level One - Primary Sensory Systems[edit | edit source]

- Infant

- 0 to 3 months

- Taking in sound, taste, vision, touch and smell

- This phase starts in the womb

Level Two - Sensory Motor Skills[edit | edit source]

- Baby to toddler

- 3 to 24 months

- Develop independent movement

- Gains body awareness and motor planning

Level Three - Perceptual Motor Skills[edit | edit source]

- 2 to 4 years old

- Speech and language

- Auditory and visual discrimination

- Eye hand coordination

- Purposeful activity

Level Four - Academic and Sport Readiness[edit | edit source]

- 5 to 7 years old

- Specialisation and automation

- Organised behaviour, postural control

- Self-esteem and self-control

When Learning and Sport go Wrong[edit | edit source]

Some children may not be ready for sports or academic learning as early as others. These children may have the following characteristics:[1]

- Poor concentration

- Fidgeting

- Inactivity / withdrawing from playground activity / sport

- Poor pencil grip

- Low academic confidence

- Physical and muscular coping strategies:

- The strong child

- The floppy child

- Pain

Ensuring that a child engages in the cycle of doing, learning and practising can help him / her to achieve writing and sport readiness:[1]

- Encourage playful learning

- Be prepared for more teaching and more practice to help a child master a skill

- Instill “grit” through understanding

- Sitting should be comfortable

- Foot support (i.e. footstool, height adjustable chair)

- If on the floor, consider how the child is sitting - alignment, midline orientation / focus of attention, static propping or weight collapsing?

- Wobble / fidget?

- Allow lots of movement

- Do not have children sitting still for more than 20 minutes (in Grade / Year 1)

- Have movement breaks:

- Send the child out on errands

- Try programmes such as Straighten Up UK Programme

- Movement plays an important part in sitting: “a school in which movement is supported and encouraged has a positive effect on the learning ability and attentiveness of the children” (Dr Dieter Breitheckerxi)[9]

- Incorporate “anti-gravity” creative play into daily routine.

- Practice sitting

- Build up to 20 minutes

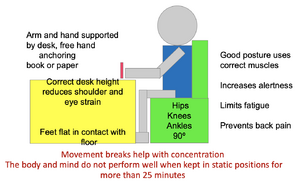

- Sit right then write (see Figure 2)

Sitting in the Classroom and at Home[edit | edit source]

If a child is not coping, it can be useful to consider how this child sits and breathes while writing. If a child is hunched over a desk, head in arms, it can lead to:

- Comments such as

- “I don’t want to do my homework”

- “It’s boring”

- “I am tired”

- Fidgeting

- Slumping

- Twisting

- Poor attention to a task

Possible solutions to these issues include:

- Adjusting the height of the chair

- It is possible to use common household items to do this such as hot water bottles, cushions, yellow pages, or with a height adjustable chair

- Raising the work surface or using an inclined sloping surface

- Feet should be placed flat on floor

- Avoid hooking feet around chairs

- Size matters (e.g. desk and chair height)[9]

- When selecting furniture in schools, age and height are often not considered, so the furniture is too big or too small, which can lead to discomfort, restlessness and, thus, affect learning

- It is possible to use wedge cushions or footstools to address size issues[1]

- Writing slopes

- Enable children to keep their hand under the line of writing

- Position and height of the desk need to work for the child. Consider in particular the set up for:[1]

- Left handed children (see below)

- Tall children

- Short children

- It can be beneficial to invest in a “homework chair” - examples include the: Sit Right, Enzi, Stokke and Ergochair

- Teach left handers letter formation by standing besides them and holding pencil in your left hand:[1]

- Position the paper to the left of the child’s midline

- Angle the paper, so that it lies parallel to the child’s forearm – close to 45 degrees

- Encourage left handed children to learn how to position the paper themselves

- To ensure correct positioning of the paper, tape an outline on the writing surface to indicate where the paper should be

- The child should grip far enough from the point to see what he or she is writing, and not smear what he or she has written

- Mark a line on the pencil to remind the child where to grip, or place a pencil grip at the appropriate spot

- Remind the child to grip the writing tool gently so as to not cause hand fatigue

- Writing large letters at first helps children learn to relax their grip - as children gain fine motor control, they will naturally reduce the size of their writing

- The wrist should be almost straight, not bent

- The hand should always be below the writing line and never cross the midline

For preschoolers, it is important to avoid W-sitting. Instead, aim for alignment with wedges and cushions and encouraging positions such as:[1]

- Kneeling

- All fours

- Playing in high kneeling

Children should also be encouraged to eat with good alignment - i.e. feet supported and a stable base.[1]

See Table 1 for drawing and playing ideas to help children become reading and writing ready and to develop good writing skills.

| Good Writing Skills | Reading and Writing Ready |

|---|---|

| Cross the midline | Sand / mud play |

| Painting | Spaghetti / string play |

| Chalk | Playdough |

| Use an upright surface | Shaving foam |

| Stick page down | Blackboards |

| Use thicker crayons | Cut out cardboard letters |

| Draw lying on your back |

The following are some practical ideas for “doing”:[1]

- Find activities that a child can “excel” at and not be the odd one out

- Group children according to ability, not age

- Facilitate independence in activities of daily living

- Buttoning

- Dressing

- Changing for PE

- Getting school bag ready

- Break down activities step by step and have a 3 step plan for each activity

- Give your children extra time

- Wake up early

- School bag choice

- Get children to exercise - consider how much is needed

- Make time for attention: yours and theirs

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Guidelines for physical activity are discussed in more detail here. Recommended daily activity:[10][11]

- 60 minutes per day for school aged children

- 120 mins for preschoolers

Recommended screen time guidelines:[10]

- No screen time access for children under the age of 2 years

- 1 to 2 hours of educational screen time for children aged 2 to 5 years

- Maximum of 2 hours screen time for children aged over 6 years

Importance of Promoting Movement[edit | edit source]

While questions remain about how physical activity can best be incorporated in schools (e.g. activity breaks vs active lessons),[12] it is important to promote movement in children for the following reasons:[1]

- Child gets stronger muscles- less fidgeting

- Relieves tight muscles- less aches and pains

- Playing and exercising helps the brain to grow and work

- Fitness may improve reading and maths scores

- Exercise training helps children to concentrate

- Movement and standing in the classroom promote concentration and focus and enhance health outcomes[13][14]

- Enhances executive control processes and other cognitive tasks / performance[15][16]

- Increased PE time (and associated decrease in academic time) does not cause a decline in academic performance[17]

Practical Ideas to Encourage Movement[edit | edit source]

- Leg balance

- Jumping

- Hopping

- Hopscotch

- Running, hiking, walking

- Leg strengthening

- Stretches/Active mobilisation/Yoga

- Sensory activities-examples

- Ball exercises - ball skills and core work

- Teach child to skip

- Teach child to ride a bike

- Teach child to do handstands and cartwheels

- Talk about posture

- Introduce healthy eating habits[1]

The “I Can” Attitude[edit | edit source]

A child needs a sense of self efficacy and agency to engage in challenging tasks. The following strategies can help to enhance a child’s intrinsic motivation:[1]

- Set SMART goals for children

- Parenting strategies

- Choose praise, reward effort and be specific with praise

- Acknowledge / validate and explain discomfort

- “I can see you find sitting still very hard”

- “The burning feeling in your legs is a sign that your muscles are getting stronger”

- “Being out of breathe means that your heart is working very hard and you are getting fitter”

- “I can see that this is tricky for you”

- Support children to manage themselves independently

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Prowse T. The Social, Cognitive and Emotional Development of Children - The Road to Writing and Moving Course. Physioplus, 2021.

- ↑ Simmonds J. Generalized joint hypermobility: a timely population study and proposal for Beighton cut-offs. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(11):1832-3.

- ↑ Barnett L, Hnatiuk J, Salmon J, Hesketh K. Modifiable factors which predict children’s gross motor competence: a prospective cohort study. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2019;16(1):129.

- ↑ Collins H, Booth JN, Duncan A, Fawkner S. The effect of resistance training interventions on fundamental movement skills in youth: a meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2019;5(1):17.

- ↑ Ayres AJ. Sensory integration and the child: Understanding hidden sensory challenges. United States: Western Psychological Services, 2005.

- ↑ Stock Kranowitz C. Out of Sync Child. Available from: https://out-of-sync-child.com (accessed 4 August 2021).

- ↑ Stanford Alumni. Developing a Growth Mindset with Carol Dweck. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiiEeMN7vbQ [last accessed 4/8/2021]

- ↑ Publicasity. Straighten Up UK!. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jioiv5AJtk4 [last accessed 4/8/2021]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 FIRA. Safe seats of learning. Hertfordshire: FIRA International Ltd. 2008

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 World Health Organsation. Physical activity. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed 2 August 2021).

- ↑ Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:1451-62.

- ↑ Donnelly JE, Hillman CH, Castelli D, Etnier JL, Lee S, Tomporowski P et al. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1197-222.

- ↑ Benden ME, Zhao H, Jeffrey CE, Wendel ML, Blake JJ. The evaluation of the impact of a stand-biased desk on energy expenditure and physical activity for elementary school students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(9):9361-75.

- ↑ Hinckson E, Salmon J, Benden M, Clemes SA, Sudholz B, Barber SE et al. Standing classrooms: research and lessons learned from around the world. Sports Med. 2016;46, 977–87.

- ↑ Sibley B, Etnier J. The relationship between physical activity and cognition in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2003;15(3):243-56.

- ↑ Tomporowski PD, Davis CL, Miller PH, Naglieri JA. Exercise and children's intelligence, cognition, and academic achievement. Educ Psychol Rev. 2008;20(2):111-31.

- ↑ Ahamed Y, Macdonald H, Reed K, Naylor PJ, Liu-Ambrose T, McKay H. School-based physical activity does not compromise children's academic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(2):371-6.