The Os Trigonum Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (73 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors ''' | '''Original Editors - '''[[User:Gaelle De Coster|Gaelle De Coster]] | ||

''' | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Definition/Description == | ||

[[Image:Os trigonum 1.png|thumb|right|292x246px|Sagittal T1-weighted MR image in plantar flexion showing the “nutcracker-phenomenon”. The os trigonum together with surrounding soft tissues are wedged between talus, calcaneus and tibia.]] | |||

The Os Trigonum Syndrome refers to pain posterior of the ankle and reduced plantarflexion caused by “the nutcracker-phenomenon”. When an os trigonum is present, this accessory ossicle together with surrounding soft tissues can become wedged between the tibia, talus and calcaneus. This can lead to inflammation of the involved structures. <ref name="p3">Physioroom. Os Trigonum Syndrome in Depth. http://www.physioroom.com/injuries/ankle_and_foot/os_trigonum_full.php (accessed 21 November 2011).</ref><ref name="p0">J. A. Russell, D.W. Kruse, Y.I. Koutedakis, I. M. Mcewan, M. A. Wyon Pathoanatomy of Posterior Ankle Impingement in Ballet Dancers. Clinical Anatomy 2010; 23:613–621</ref><ref name="p8">M. Nyska, G. Mann Unstable Ankle. Leeds: Human Kinetics Publishers, 2002.</ref> | |||

The os trigonum syndrome can also be named the symptomatic os trigonum, the talar compression syndrome or posterior tibial talar impingement syndrome.<ref name="p5">D. Karasick, M. E. Schweitzer The OsTrigonum Syndrome: Imaging Features. AJR 1996; 166:125-129</ref> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

== | Embryologically, the body of the talus and the posterior talar process are separate ossification centers. Between the 7th and the 13th year of life, the posterior talar process appears as a separate ossicle: the os trigonum. Normally, within a year of its appearance, it fuses with the talus, but about 7% of the adult population has still this os trigonum. It can be present unilaterally or bilaterally, with smooth or serrated margins. The os trigonum is usually seen as an individual bone, but can also exist of two or more pieces. It is less than 1cm in size, but this can vary. <ref name="p8" /><ref name="p1">J. Zeichen, E. Schratt, U. Bosch, H. Thermann Das Os-trigonum-syndrom. Unfallchirurg 1999; 102:320±323</ref> <ref name="p5" /> | ||

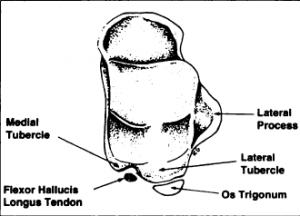

[[Image:Os trigonum 6.png|thumb|left|Superior view of talus]] | |||

= | The os trigonum is usually triangular with an anterior, inferior and posterior surface. The anterior surface connects with the lateral tubercle by cartilaginous synchondrosis. The inferior side may articulate with the calcaneus. The posterior surface is nonarticular, but is used as a point of attachment for capsuloligamentous structures. The os trigonum may also be round or oval. <ref name="p5" /> | ||

The | The flexor hallucis longus tendon is situated medial to the os trigonum, in the sulcus between the medial and lateral tubercle.<ref name="p5" /><br> | ||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

There are three mechanisms for the development of an os trigonum: | |||

= | #fusion failure of an ossification center | ||

#fracture of the posterior margin of the tibia | |||

#fracture of the posterior process of the talus.<ref name="p9">W. Albisetti, M. Ometti, V. Pascale, O. De Bartolomeo Clinical Evaluation and Treatment of Posterior Impingement in Dancers. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008; 88:349–354.</ref><br> | |||

The presence of an os trigonum isn’t sufficient to create the syndrome. It must be combined with a traumatic event. <ref name="p8" /> | |||

The os trigonum syndrome can be caused by overuse or trauma. When it’s due to overuse, it’s mostly found by ballet dancers and runners. The forceful plantar flexion that happens during an “en pointe” or “demi-pointe” position, as well as by running downhill, produces compression on the posterior aspect of the ankle joint. In cause of a trauma, the os trigonum can be displaced by forced plantarflexion. <ref name="p8" /> | |||

Soft tissue structures, including the ankle joint capsule and surrounding ligaments, may react by forming a hypertrophic mass. <ref name="p5" /><ref name="p0" /> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

A load-dependent, persistent pain between the Achilles tendon and the peroneal tendons is the first indicator of the syndrome. Stiffness, weakness and swelling can also be observed in this zone. The second main symptom is a decrease in plantarflexion compared with the unaffected ankle. In some cases the bony prominence may be palpable.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p9" /><ref name="p3" /><ref name="p7">T. H. Berquist Imaging of the Foot and Ankle. 2010</ref> | |||

< | Eversion or inversion movements may cause discomfort. Pain at the posterior aspect of the ankle will be experienced by plantarflexion of the foot or dorsiflexion of the great toe.<ref name="p5" /><ref name="p2">D. R. Tollafield, L. M. Merriman Clinical skills in treating the foot. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.</ref> | ||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

The following diagnosis must be considered: | |||

< | *Tendinitis flexor hallucis longus<ref name="p8" />;*Tarsal tunnel syndrome<ref name="p8" />;*Subtalar pathology<ref name="p8" />;*Achilles tendinopathy<ref name="p1" />;*Peroneal tendinopathy<ref name="p1" />;*Achilles tendon bursitis<ref name="p1" />;*Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. <ref name="p1" /> | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

*Lateral X-ray<ref name="p2" />, possibly weight-bearing, with the foot in full plantarflexion.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

*CT-scan<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p1" /> | |||

*MRI is the preferable technique<ref name="p5" /> for establishing the presence<ref name="p6">D. B. Thordarson Foot and Ankle. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.</ref> and the size of the ossicle<ref name="p2" />, coexisting pathologies and soft tissue and bone damage.<ref name="p9" /> Flexion/extension MRI gives information about the mobility of the os trigonum.<ref name="p5" /> | |||

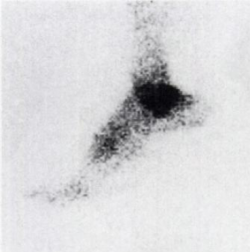

*Technetium bone scan<ref name="p9" /><ref name="p1" /><ref name="p6" /> shows increased uptake in the region of the os trigonum. | |||

{| | |||

|- | |||

| [[Image:Os trigonum 4.png|thumb|left|222x299px|lateral x-ray of foot showing os trigonum]] | |||

| [[Image:Os trigonum 3.png|thumb|left|250x252px|Technetium bone scan]] | |||

|} | |||

== Examination == | |||

== | On posterolateral palpation, between the Achilles tendon and peroneal tendons, pain and swelling may be noticed.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /><ref name="p8" /> | ||

The passive forced plantarflexion test: It should be executed with repetitive quick and passive hyperplantarflexion movements in a neutral position, possibly with exo- or endorotation movement on the point of maximal plantarflexion. Thereby grinds the ossicle between tibia and calcaneus.<ref name="p8" /><br> | |||

== | == Medical Management == | ||

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication or corticosteroid injections are used to reduce soft tissue inflammation.<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p3" /><ref name="p8" /><br>In case of fracture, a below-knee cast is used for 4-6weeks.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

== | If symptoms persist, surgery is applied. (high evidence, all studies mention good results.)<br>This involves the removal of the os trigonum. Postoperatively we apply a plaster cast for 5days. Hereafter physiotherapy is started for 4-8 weeks. Afterwards full sports activities can be resumed. It will take up to 6 months until full recovery.<ref name="p3" /><ref name="p8" /><br> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

< | Rest, ice, massage and ultrasound treatment will reduce inflammation.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2" /><ref name="p8" /> | ||

< | Isometric and eccentric exercises to strengthen and stretch the lower-leg muscles are used in a physiotherapeutic treatment.<ref name="p9" /> | ||

= | Also exercises to improve deep muscle action during plantarflexion are designated. The deep muscles of the lower leg, such as tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus and the peroneals are the opposites of the M.gastrocnemius. By using the deep muscles, the talus is shifted forward during plantarflexion, what will reduce the impact of the os trigonum on the posterior tibia, contrary to using the M.gastrocnemius, which results in lifting the calcaneus and compression of the os trigonum.<ref name="p9" /> | ||

<u>[[Image:Os trigonum 5.png|left|800x216px]]</u> | |||

= | <u>Fig. 5</u>: Strengthening of the deep muscles. Performing demipointe (2) and en pointe (3) while holding the calcaneus in place with the hands. Knee flexion at 90° to prevent contraction of the M.gastrocnemius.<ref name="p9" /> | ||

Also, proprioceptive exercises on a tilt board are applied to correct malalignments of the lower limb.<ref name="p9" /><br>All of these exercises were found in only one study of 11 dancers with a posterior ankle impingement including 6 cases with an os trigonum. Nine of them had good results with these exercises, the other two ones underwent surgical excision.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

= | According to a recent systematic review, physiotherapeutic interventions have positive effects in several domains, including pain, ROM, and functional status, having a potential role in the treatment of ballet dancers after injuries. However, the small evidence base and methodological limitation of this review calls for a cautious approach while considering the physiotherapy options for managing injuries in a ballet dancer.<ref>Skwiot M, Śliwiński Z, Żurawski A, Śliwiński G. [https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0253437 Effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for injury in ballet dancers: A systematic review]. PLoS one. 2021 Jun 24;16(6):e0253437.</ref> | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 98: | Line 95: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project | [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Primary Contact]] | |||

[[Category:Syndromes]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:29, 16 July 2021

Original Editors - Gaelle De Coster

Top Contributors - Gaelle De Coster, Admin, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Claire Knott, Rachael Lowe, Wanda van Niekerk, 127.0.0.1 and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

The Os Trigonum Syndrome refers to pain posterior of the ankle and reduced plantarflexion caused by “the nutcracker-phenomenon”. When an os trigonum is present, this accessory ossicle together with surrounding soft tissues can become wedged between the tibia, talus and calcaneus. This can lead to inflammation of the involved structures. [1][2][3]

The os trigonum syndrome can also be named the symptomatic os trigonum, the talar compression syndrome or posterior tibial talar impingement syndrome.[4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Embryologically, the body of the talus and the posterior talar process are separate ossification centers. Between the 7th and the 13th year of life, the posterior talar process appears as a separate ossicle: the os trigonum. Normally, within a year of its appearance, it fuses with the talus, but about 7% of the adult population has still this os trigonum. It can be present unilaterally or bilaterally, with smooth or serrated margins. The os trigonum is usually seen as an individual bone, but can also exist of two or more pieces. It is less than 1cm in size, but this can vary. [3][5] [4]

The os trigonum is usually triangular with an anterior, inferior and posterior surface. The anterior surface connects with the lateral tubercle by cartilaginous synchondrosis. The inferior side may articulate with the calcaneus. The posterior surface is nonarticular, but is used as a point of attachment for capsuloligamentous structures. The os trigonum may also be round or oval. [4]

The flexor hallucis longus tendon is situated medial to the os trigonum, in the sulcus between the medial and lateral tubercle.[4]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are three mechanisms for the development of an os trigonum:

- fusion failure of an ossification center

- fracture of the posterior margin of the tibia

- fracture of the posterior process of the talus.[6]

The presence of an os trigonum isn’t sufficient to create the syndrome. It must be combined with a traumatic event. [3]

The os trigonum syndrome can be caused by overuse or trauma. When it’s due to overuse, it’s mostly found by ballet dancers and runners. The forceful plantar flexion that happens during an “en pointe” or “demi-pointe” position, as well as by running downhill, produces compression on the posterior aspect of the ankle joint. In cause of a trauma, the os trigonum can be displaced by forced plantarflexion. [3]

Soft tissue structures, including the ankle joint capsule and surrounding ligaments, may react by forming a hypertrophic mass. [4][2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

A load-dependent, persistent pain between the Achilles tendon and the peroneal tendons is the first indicator of the syndrome. Stiffness, weakness and swelling can also be observed in this zone. The second main symptom is a decrease in plantarflexion compared with the unaffected ankle. In some cases the bony prominence may be palpable.[5][6][1][7]

Eversion or inversion movements may cause discomfort. Pain at the posterior aspect of the ankle will be experienced by plantarflexion of the foot or dorsiflexion of the great toe.[4][8]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following diagnosis must be considered:

- Tendinitis flexor hallucis longus[3];*Tarsal tunnel syndrome[3];*Subtalar pathology[3];*Achilles tendinopathy[5];*Peroneal tendinopathy[5];*Achilles tendon bursitis[5];*Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. [5]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Lateral X-ray[8], possibly weight-bearing, with the foot in full plantarflexion.[6]

- CT-scan[8][5]

- MRI is the preferable technique[4] for establishing the presence[9] and the size of the ossicle[8], coexisting pathologies and soft tissue and bone damage.[6] Flexion/extension MRI gives information about the mobility of the os trigonum.[4]

- Technetium bone scan[6][5][9] shows increased uptake in the region of the os trigonum.

Examination [edit | edit source]

On posterolateral palpation, between the Achilles tendon and peroneal tendons, pain and swelling may be noticed.[5][7][3]

The passive forced plantarflexion test: It should be executed with repetitive quick and passive hyperplantarflexion movements in a neutral position, possibly with exo- or endorotation movement on the point of maximal plantarflexion. Thereby grinds the ossicle between tibia and calcaneus.[3]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication or corticosteroid injections are used to reduce soft tissue inflammation.[8][1][3]

In case of fracture, a below-knee cast is used for 4-6weeks.[8]

If symptoms persist, surgery is applied. (high evidence, all studies mention good results.)

This involves the removal of the os trigonum. Postoperatively we apply a plaster cast for 5days. Hereafter physiotherapy is started for 4-8 weeks. Afterwards full sports activities can be resumed. It will take up to 6 months until full recovery.[1][3]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Rest, ice, massage and ultrasound treatment will reduce inflammation.[5][8][3]

Isometric and eccentric exercises to strengthen and stretch the lower-leg muscles are used in a physiotherapeutic treatment.[6]

Also exercises to improve deep muscle action during plantarflexion are designated. The deep muscles of the lower leg, such as tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus and the peroneals are the opposites of the M.gastrocnemius. By using the deep muscles, the talus is shifted forward during plantarflexion, what will reduce the impact of the os trigonum on the posterior tibia, contrary to using the M.gastrocnemius, which results in lifting the calcaneus and compression of the os trigonum.[6]

Fig. 5: Strengthening of the deep muscles. Performing demipointe (2) and en pointe (3) while holding the calcaneus in place with the hands. Knee flexion at 90° to prevent contraction of the M.gastrocnemius.[6]

Also, proprioceptive exercises on a tilt board are applied to correct malalignments of the lower limb.[6]

All of these exercises were found in only one study of 11 dancers with a posterior ankle impingement including 6 cases with an os trigonum. Nine of them had good results with these exercises, the other two ones underwent surgical excision.[6]

According to a recent systematic review, physiotherapeutic interventions have positive effects in several domains, including pain, ROM, and functional status, having a potential role in the treatment of ballet dancers after injuries. However, the small evidence base and methodological limitation of this review calls for a cautious approach while considering the physiotherapy options for managing injuries in a ballet dancer.[10]

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Physioroom. Os Trigonum Syndrome in Depth. http://www.physioroom.com/injuries/ankle_and_foot/os_trigonum_full.php (accessed 21 November 2011).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 J. A. Russell, D.W. Kruse, Y.I. Koutedakis, I. M. Mcewan, M. A. Wyon Pathoanatomy of Posterior Ankle Impingement in Ballet Dancers. Clinical Anatomy 2010; 23:613–621

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 M. Nyska, G. Mann Unstable Ankle. Leeds: Human Kinetics Publishers, 2002.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 D. Karasick, M. E. Schweitzer The OsTrigonum Syndrome: Imaging Features. AJR 1996; 166:125-129

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 J. Zeichen, E. Schratt, U. Bosch, H. Thermann Das Os-trigonum-syndrom. Unfallchirurg 1999; 102:320±323

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 W. Albisetti, M. Ometti, V. Pascale, O. De Bartolomeo Clinical Evaluation and Treatment of Posterior Impingement in Dancers. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008; 88:349–354.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 T. H. Berquist Imaging of the Foot and Ankle. 2010

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 D. R. Tollafield, L. M. Merriman Clinical skills in treating the foot. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 D. B. Thordarson Foot and Ankle. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

- ↑ Skwiot M, Śliwiński Z, Żurawski A, Śliwiński G. Effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for injury in ballet dancers: A systematic review. PLoS one. 2021 Jun 24;16(6):e0253437.