The Flag System

Original Editor - The Open Physio project.

Top Contributors - Admin, Faye Underwood, Rachael Lowe, Scott Buxton, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Venus Pagare, Adam Vallely Farrell, Luke Dinan, Claire Knott, Amanda Ager, Jess Bell and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Yellow flags are psychosocial indicators suggesting increased risk of progression to long-term distress, disability and pain.

A biopsychosocial assessment should seek to identify the following:

- Bio (pathology)

- Psycho (psychological distress, fear/avoidance beliefs, current coping methods and attribution)

- Social (work issues, family circumstances and benefits/economics)

Key predictors include:

- The belief that pain is harmful or severely disabling

- Fear-avoidance behaviour (avoiding activity because of fear of pain)

- Low mood and social withdrawal

- Expectation that passive treatment rather than active participation will help

Assessing for yellow flags[edit | edit source]

While performing a Yellow Flag assessment, the following should be acknowledged:

- Attitudes/Beliefs – What does the patient think to be the problem and do they have a positive or negative attitude to the pain and potential treatment?

- Behaviour – Has the patient changed their behaviour to the pain? Have they reduced activity or compensating for certain movements. Early signs of catastrophising and fear-avoidance?

- Compensation – Are they awaiting a claim due to a potential accident? Is this placing unnecessary stress on their life? .

- Diagnosis/Treatment – Has the language that has been used had an effect on patient thoughts? Have they had previous treatment for the pain before, and was there a conflicting diagnosis? This could cause the patient to over-think the issue, leading to catastrophising and fear-avoidance.

- Emotions – Does the patient have any underlying emotional issues that could lead to an increased potential for chronic pain? Collect a thorough background on their psychological history.

- Family – How are the patient’s family reacting to their injury? Are they being under-supportive or over-supportive, both of which can effect the patient’s concept of their pain

- Work – Are they currently off work? Financial issues could potentially arise? What are the patient’s thoughts about their working environment?

Clinical Assessment of Psychosocial Yellow Flags[1]

Fear-Avoidance Model[edit | edit source]

Another psychological issue associated with chronic pain is catastrophizing, which is outlined through the Fear Avoidance Model.

Fear is the emotional reaction to a specific, identifiable and immediate threat, such as a dangerous injury [2]. Fear may protect the individual from impeding danger as it instigates the defensive behaviour that is associated with the fight or flight response [3].

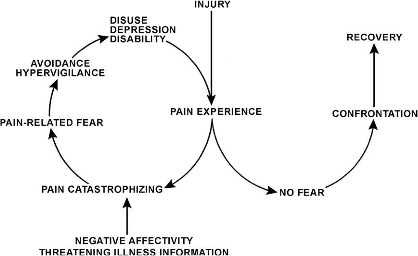

The Fear-Avoidance Model was designed to identify and explain why chronic low back pain problems, and associated disability, develop in members of the population suffering from an onset of low back pain [4]. This model indicates that a person suffering from pain will undergo one of two different pathways (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Fear Avoidance Model [5]

This shows that when pain/injury occurs, people will take the path of continuing their independence without negative thoughts of the pain they are suffering from, therefore leading them to accept that they have this pain that ultimately accumulates to a faster recovery. In contrast to this, a cycle can be initiated if the pain is misinterpreted in a catastrophising manner. It has been recognised that these thoughts can lead on to pain-related fear and associated safety seeking behaviours, such as avoidance. However, this could cause the pain to become worse and enter a chronic phase due to the disuse and disability. This in turn can lower the threshold at which the person will experience pain.

Treating yellow flags[edit | edit source]

The early treatment of patients at risk of developing chronic pain has been found to be effective at preventing long-term disability and chronicity.

Stepped care approach[edit | edit source]

People with pain require:

- a rationale for returning to activity

- an appropriate strategy to manage their symptoms

- a safe environment to engage in physical exercise to restore confidence in movement

- the opportunity and encouragement to return to normal physical activity

In addressing the factors above, the difference between treatment and rehabilitation becomes clearer but must still take into account the barriers to rehabilitation. These are the non-physical or clinical factors that are important to determine recovery and failure to address them can lead to a suboptimal outcome, no matter how technically good you are as a clinician (Waddell & Watson, 2004).

Von Korff and Moore (2001) advocate a stepped care approach, evident in the following table:

| 1. | Most patients who are at the acute stage | Identify and address the common worries of patients with back pain using simple, symptomatic measures. Provide information and advice to encourage the resumption of ordinary activities. |

| 2. |

The substantial minority of patients who do not resume ordinary activities by 3-6 weeks with simple advice. |

Provide brief, structured interventions that help patients to identify obstacles to recovery, set functional goals and develop plans to achieve them. Provide support for physical exercise and return to ordinary activities |

| 3. | The small minority of patients who have persisting disability in work or family life and who require more intensive intervention. | Address dysfunctional beliefs and behaviour. Provide a progressive exercise or graded activity programme. Enable and support patients to return to ordinary activities. |

Cognitive behavioural approach[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a method that can help manage problems by changing the way patients would think and behave. It is not designed to remove any problems but help manage them in a positive manner [6] [7].

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1nq_IKqRo1llVnYIIPGbnRvZqENaXadrWD-KrqOcvO7U6PZkS9|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kendall, N A S, Linton, S J & Main, C J (1997). Guide to Assessing Psycho-social Yellow Flags in Acute Low Back Pain: Risk Factors for Long-Term Disability and Work Loss. Accident Compensation Corporation and the New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington, New Zealand. (Oct, 2004 Edition).

- ↑ Rachman, S., 1998. Anxiety. Psychological Press: Hove

- ↑ Cannon, W. B., 1929. Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage: an account of recent researches into the functions of emotional excitement. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York

- ↑ Leeuw, M., Goossens, E.J.B., Linton, S., Crombez, G., Boersma, K., Vlaeyen, J., 2007. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 30(1): 77-94

- ↑ www.psychomaticmedicine.org (2014) Fear Avoidance Model (photograph). Available at: http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/cgi/content-nw/full/67/5/783/F117 (Accessed 11th January 2014)

- ↑ Beck, J., 1995. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Guildford Press: New York

- ↑ NHS Choices, 2012. Cognitive behavioural therapy. [online] Available at: <http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cognitive-behavioural-therapy/Pages/Introduction.aspx [Accessed 8th Jan 2014]