Tendinopathy Rehabilitation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

Despite recent advances in research tendinopathy rehab remains somewhat in its infancy. Our management of this condition is very different now than 10 years ago and 10 years from now will likely see different treatments again. There appears to be a bountiful supply of theoretical research but little in terms of high quality clinical trials. By this I mean that we have established a host of theories on tendon pathology, function and rehab but we have surprisingly few high quality studies proving clinically significant improvement from treatment. | |||

Peter Malliaras et al<ref>Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236048688_Achilles_and_Patellar_Tendinopathy_Loading_Programmes_A_Systematic_Review_Comparing_Clinical_Outcomes_and_Identifying_Potential_Mechanisms_for_Effectiveness Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness]. Sports Med. 2013 Apr;43(4):267-86.</ref> reviewed the literature recently on loading programmes for achilles and patellar tendinopathy (2 of the most common) and found a number of methodological flaws. Just 2 studies were deemed ‘high quality’, only 2 described adequate blinding and the majority did not use a validated outcome measure. They also found that around 45% of patients didn’t improve significantly with exercise programmes. So, while we can make some recommendations, there is still some way to go before we have conclusive evidence on tendinopathy rehab. | |||

The development of a rehabilitation plan for an individual presenting with confirmed symptomatic tendinopathy requires complex clinical reasoning, with reference to the pathoanatomical diagnosis. Tendon pathology and subsequent rehabilitation will vary considerably depending on the site of pathology; stage of the tendinopathy; functional assessment; activity status of the person; contributing issues throughout the kinetic chain; comorbidities; and concurrent presentations<ref name="Scott et al" />. | The development of a rehabilitation plan for an individual presenting with confirmed symptomatic tendinopathy requires complex clinical reasoning, with reference to the pathoanatomical diagnosis. Tendon pathology and subsequent rehabilitation will vary considerably depending on the site of pathology; stage of the tendinopathy; functional assessment; activity status of the person; contributing issues throughout the kinetic chain; comorbidities; and concurrent presentations<ref name="Scott et al" />. | ||

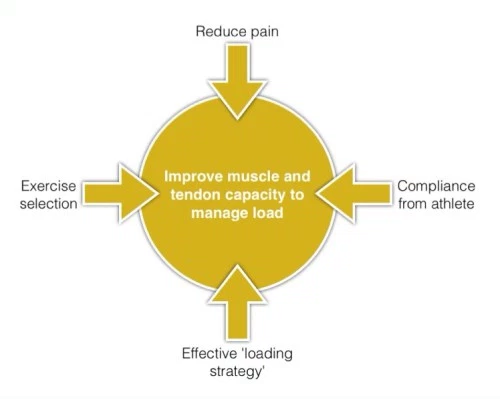

Our key goal in tendinopathy | There are many treatment options for tendinopathy and many factors to consider, it can be helpful to think of what our main treatment goal is and keep this in mind. Our key goal in tendinopathy rehab is improving the capacity of the tendon and muscle to manage load. Tendon and muscle function together as a musculotendinous unit – we need to consider this in rehab, not just the tendon.<ref name="Goon1">Goon T. Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1. Accessed online at [http://www.running-physio.com/tendinopathy1/ Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1] 30 Jan 2016</ref>. Each component of the rehabilitation programme, in particular loading, must be manipulated in relation to the nature, speed and magnitude of the forces applied to the muscle/tendon/bone unit in order to achieve the goals of the particular management phase without causing an exacerbation of the pathological state or pain<ref name="Scott et al">Alex Scott, Sean Docking, Bill Vicenzino, Håkan Alfredson, Johannes Zwerver, Kirsten Lundgreen, Oliver Finlay, Noel Pollock, Jill L Cook, Angela Fearon, Craig R Purdam, Alison Hoens, Jonathan D Rees, Thomas J Goetz, Patrik Danielson. [http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2013/04/11/bjsports-2013-092329.full.html Sports and exercise-related tendinopathies: a review of selected topical issues by participants of the second International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium (ISTS) Vancouver 2012]. Br J Sports Med doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092329</ref>. | ||

[[Image:Management of tendinopathy.png|center]] | |||

== Rehabilitation Progression == | == Rehabilitation Progression == | ||

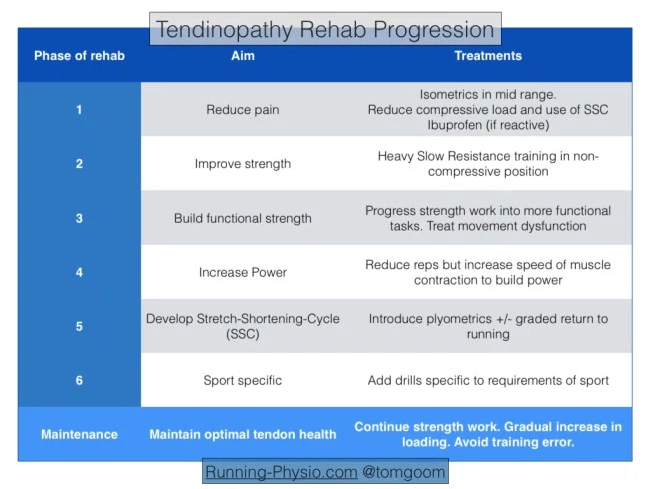

Goon<ref name="Goon1" /><ref name="Goon2">Goon T. Tendinopathy – functional rehab. Accessed online at [http://www.running-physio.com/tendinopathy2/ Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1] 30 Jan 2016</ref> suggests considering | The aim of any rehabiitation strategy is to progress from pain to performance. Goon<ref name="Goon1" /><ref name="Goon2">Goon T. Tendinopathy – functional rehab. Accessed online at [http://www.running-physio.com/tendinopathy2/ Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1] 30 Jan 2016</ref> suggests considering this in phases: | ||

[[Image:Tendinopathy rehab progression.png|center]] | [[Image:Tendinopathy rehab progression.png|center]] | ||

| Line 18: | Line 24: | ||

=== Phase 1 - reduce pain<br> === | === Phase 1 - reduce pain<br> === | ||

The first aim with managing tendinopathy is often to reduce pain. It is usually the most troubling complaint for a patient and pain in the tendon can lead to reduced activity in the muscle it’s attached to. Henriksen et al<ref>Henriksen M, Aaboe J, Graven-Nielsen T, Bliddal H, Langberg H. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20542970 Motor responses to experimental Achilles tendon pain]. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Apr;45(5):393-8.</ref> tested the effect of experimentally induced achilles tendon pain. They found that tendon pain causes “widespread and reduced motor responses with functional effects on the ground reaction force“. | |||

Pain will often be more severe during a reactive tendinopathy. Typically the tendon swells in response to an increase in load. This has been described in more detail in our previous piece linked above. In short phase 1 is essentially about reducing pain in a reactive tendon (whether this is truly reactive or a reactive response on top of an underlying degenerate tendon). | |||

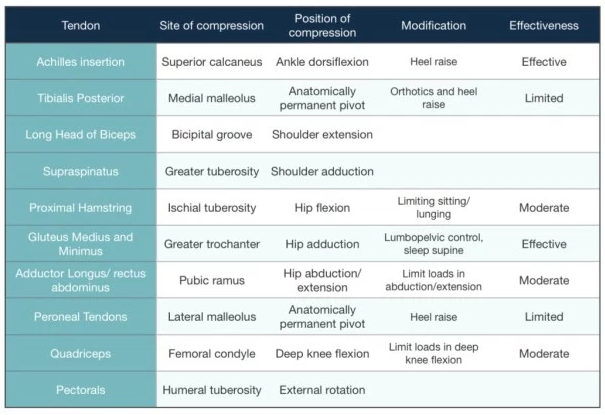

Key to reducing pain is managing the load on the tendon: | |||

#Avoid activities that place a compressive load on the tendon, usually this is any activity that would involve stretching the effected muscle or direct tendon compression. | #Avoid activities that place a compressive load on the tendon, usually this is any activity that would involve stretching the effected muscle or direct tendon compression.<br><br>[[Image:Tendon compression.png|center]]<br> | ||

#Cut out activities that involve the Stretch-Shortening-Cycle (SSC) which occurs when the tendon has to behave a like a spring, stretching then shortening to store and then release energy. | #Cut out activities that involve the Stretch-Shortening-Cycle (SSC) which occurs when the tendon has to behave a like a spring, stretching then shortening to store and then release energy. | ||

#Isometric exercises can help to reduce pain<ref name="Rio1">Ebonie Rio, Dawson Kidgell, Craig Purdam, Jamie Gaida, G Lorimer Moseley, Alan J Pearce, Jill Cook. [http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/19/1277.abstract?cited-by=yes&amp;legid=bjsports;49/19/1277 Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy]. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1277–1283.</ref><ref name="Rio2">Mathijs van Arka, Jill L. Cookb, Sean I. Dockingb, Johannes Zwervera, James E. Gaidab, Inge van den Akker-Scheeka, Ebonie Riob. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1440244015002315 Do isometric and isotonic exercise programs reduce pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy in-season? A randomised clinical trial]. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, available online 7 December 2015</ref>. These exercises should be done in a position where there is no tendon compression, usually in the mid-range of the muscle. | #Isometric exercises can help to reduce pain<ref name="Rio1">Ebonie Rio, Dawson Kidgell, Craig Purdam, Jamie Gaida, G Lorimer Moseley, Alan J Pearce, Jill Cook. [http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/19/1277.abstract?cited-by=yes&amp;amp;legid=bjsports;49/19/1277 Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy]. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1277–1283.</ref><ref name="Rio2">Mathijs van Arka, Jill L. Cookb, Sean I. Dockingb, Johannes Zwervera, James E. Gaidab, Inge van den Akker-Scheeka, Ebonie Riob. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1440244015002315 Do isometric and isotonic exercise programs reduce pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy in-season? A randomised clinical trial]. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, available online 7 December 2015</ref>. These exercises should be done in a position where there is no tendon compression, usually in the mid-range of the muscle. They can be repeated several times a day, utilising 40-60 s holds, 4-5 times, to reduce pain and maintain some muscle capacity and tendon load. In highly irritable tendons, a bilateral exercise, shorter holding time and fewer repetitions per day may be indicated<ref>J L Cook, C R Purdam. [http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2013/05/09/bjsports-2012-092078.abstract The challenge of managing tendinopathy in competing athletes]. Cook JL, | ||

Purdam CR. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:506-509</ref>. | |||

#Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen can be used to help to reduce the reactive response. | #Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen can be used to help to reduce the reactive response. | ||

=== Phase 2 - improve stength === | === Phase 2 - improve stength === | ||

Once pain has settled you can progress to phase 2 and work on strength. Research has focused on tendinopathy loading programmes that generally fit within 3 categories eccentric, combined or heavy slow resistance training. Goon<ref name="Goon1" /> summarises the evidence for lower limb strength programmes: | Once pain has settled you can progress to phase 2 and work on strength. Strength is the ability to produce force and in this context we are aiming to improve the muscle and tendon’s ability to produce force and manage load. Muscle and tendon respond to load but it is thought that repetitive loading, such as walking or running, is unlikely to stimulate significant adaptive changes. Instead '''heavy load''' is needed to promote changes in muscle and tendon that improve their load capacity. Strength is an essential building block for muscle function, without adequate strength muscle will have poor power and endurance. | ||

There are a number of options available to us in terms of exercise prescription, there is no recipe for this. It will depend on levels of pain and areas of weakness, patient goals and requirements of their sport. The question is how much strength is needed? In general we aim to achieve equal strength left and right and this can be measured using 10 rep max (10RM – maximum weight you can lift 10 times). | |||

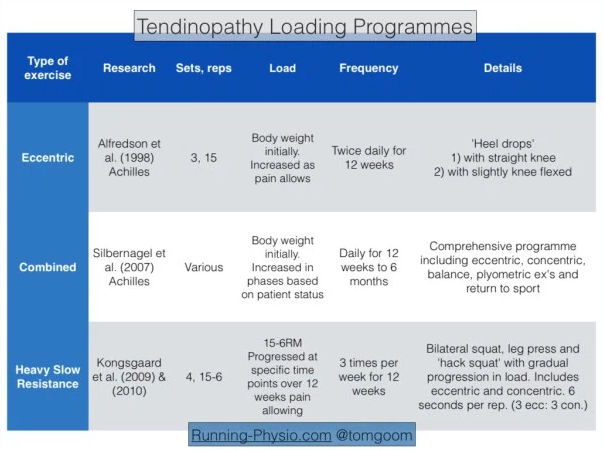

Research has focused on tendinopathy loading programmes that generally fit within 3 categories eccentric, combined or heavy slow resistance training. Goon<ref name="Goon1" /> summarises the evidence for lower limb strength programmes: | |||

[[Image:Tendinopathy Loading programmes.png|center]]<span style="font-size: 13.28px; line-height: 19.92px;">For this phase of rehab you are aiming to achieve strength changes by exercising with sufficient load in a a muscle’s mid-range position. Avoid exercising with heavy loads in positions where there is likely to be tendon compression</span><span style="font-size: 13.28px; line-height: 19.92px;">. Following research by Alfredson et al<ref>Håkan Alfredson, Tom Pietilä, Per Jonsson and Ronny Lorentzon. [http://yaroslavvb.com/papers/alfredson-heavy.pdf Heavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For the Treatment of Chronic Achilles Tendinosis]. Am J Sports Med 1998 26: 360</ref>. eccentric exercises have been considered the gold standard for many years. More recently research has demonstrated the importance of also including the concentric phase of exercises with heavy slow resistance training<ref name="Gaida">Gaida JE1, Cook J. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23531972 Treatment options for patellar tendinopathy: critical review]. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011 Sep-Oct;10(5):255-70.</ref>.</span> | |||

<span style="font-size: 13.28px; line-height: 19.92px;">Heavy Slow Resistance training (HSR) has emerged more recently as another exercise option. Gaida and Cook<ref name="Gaida" /> discuss HSR and eccentric exercise briefly in their 2011 paper on patellar tendinopathy. They note there are pros and cons of each approach; eccentric work is often prescribed as a high frequency exercise – with Alfredson’s work recommending 3 x 15 reps of 2 exercises done twice per day. HSR by contrast is usually done 2-3 times per week but in many cases will require access to gym equipment.</span> | |||

HSR involves using high loads – approx. 70-85% of 1RM (1RM – 1 repetition maximum – refers to the maximal weight you can lift once with good technique). Determining 1RM is difficult, especially in patients with pain so it can be approximated. 80% of 1RM is roughly equal to 8RM i.e. the maximal weight you can lift 8 times with good technique. | |||

<br> | |||

== Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | == Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | ||

Revision as of 09:21, 31 January 2016

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Admin, Rachael Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Rucha Gadgil, Wanda van Niekerk, Lucinda hampton, Robin Tacchetti, 127.0.0.1, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami and Claire Knott

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Despite recent advances in research tendinopathy rehab remains somewhat in its infancy. Our management of this condition is very different now than 10 years ago and 10 years from now will likely see different treatments again. There appears to be a bountiful supply of theoretical research but little in terms of high quality clinical trials. By this I mean that we have established a host of theories on tendon pathology, function and rehab but we have surprisingly few high quality studies proving clinically significant improvement from treatment.

Peter Malliaras et al[1] reviewed the literature recently on loading programmes for achilles and patellar tendinopathy (2 of the most common) and found a number of methodological flaws. Just 2 studies were deemed ‘high quality’, only 2 described adequate blinding and the majority did not use a validated outcome measure. They also found that around 45% of patients didn’t improve significantly with exercise programmes. So, while we can make some recommendations, there is still some way to go before we have conclusive evidence on tendinopathy rehab.

The development of a rehabilitation plan for an individual presenting with confirmed symptomatic tendinopathy requires complex clinical reasoning, with reference to the pathoanatomical diagnosis. Tendon pathology and subsequent rehabilitation will vary considerably depending on the site of pathology; stage of the tendinopathy; functional assessment; activity status of the person; contributing issues throughout the kinetic chain; comorbidities; and concurrent presentations[2].

There are many treatment options for tendinopathy and many factors to consider, it can be helpful to think of what our main treatment goal is and keep this in mind. Our key goal in tendinopathy rehab is improving the capacity of the tendon and muscle to manage load. Tendon and muscle function together as a musculotendinous unit – we need to consider this in rehab, not just the tendon.[3]. Each component of the rehabilitation programme, in particular loading, must be manipulated in relation to the nature, speed and magnitude of the forces applied to the muscle/tendon/bone unit in order to achieve the goals of the particular management phase without causing an exacerbation of the pathological state or pain[2].

Rehabilitation Progression[edit | edit source]

The aim of any rehabiitation strategy is to progress from pain to performance. Goon[3][4] suggests considering this in phases:

Phase 1 - reduce pain

[edit | edit source]

The first aim with managing tendinopathy is often to reduce pain. It is usually the most troubling complaint for a patient and pain in the tendon can lead to reduced activity in the muscle it’s attached to. Henriksen et al[5] tested the effect of experimentally induced achilles tendon pain. They found that tendon pain causes “widespread and reduced motor responses with functional effects on the ground reaction force“.

Pain will often be more severe during a reactive tendinopathy. Typically the tendon swells in response to an increase in load. This has been described in more detail in our previous piece linked above. In short phase 1 is essentially about reducing pain in a reactive tendon (whether this is truly reactive or a reactive response on top of an underlying degenerate tendon).

Key to reducing pain is managing the load on the tendon:

- Avoid activities that place a compressive load on the tendon, usually this is any activity that would involve stretching the effected muscle or direct tendon compression.

- Cut out activities that involve the Stretch-Shortening-Cycle (SSC) which occurs when the tendon has to behave a like a spring, stretching then shortening to store and then release energy.

- Isometric exercises can help to reduce pain[6][7]. These exercises should be done in a position where there is no tendon compression, usually in the mid-range of the muscle. They can be repeated several times a day, utilising 40-60 s holds, 4-5 times, to reduce pain and maintain some muscle capacity and tendon load. In highly irritable tendons, a bilateral exercise, shorter holding time and fewer repetitions per day may be indicated[8].

- Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen can be used to help to reduce the reactive response.

Phase 2 - improve stength[edit | edit source]

Once pain has settled you can progress to phase 2 and work on strength. Strength is the ability to produce force and in this context we are aiming to improve the muscle and tendon’s ability to produce force and manage load. Muscle and tendon respond to load but it is thought that repetitive loading, such as walking or running, is unlikely to stimulate significant adaptive changes. Instead heavy load is needed to promote changes in muscle and tendon that improve their load capacity. Strength is an essential building block for muscle function, without adequate strength muscle will have poor power and endurance.

There are a number of options available to us in terms of exercise prescription, there is no recipe for this. It will depend on levels of pain and areas of weakness, patient goals and requirements of their sport. The question is how much strength is needed? In general we aim to achieve equal strength left and right and this can be measured using 10 rep max (10RM – maximum weight you can lift 10 times).

Research has focused on tendinopathy loading programmes that generally fit within 3 categories eccentric, combined or heavy slow resistance training. Goon[3] summarises the evidence for lower limb strength programmes:

For this phase of rehab you are aiming to achieve strength changes by exercising with sufficient load in a a muscle’s mid-range position. Avoid exercising with heavy loads in positions where there is likely to be tendon compression. Following research by Alfredson et al[9]. eccentric exercises have been considered the gold standard for many years. More recently research has demonstrated the importance of also including the concentric phase of exercises with heavy slow resistance training[10].

Heavy Slow Resistance training (HSR) has emerged more recently as another exercise option. Gaida and Cook[10] discuss HSR and eccentric exercise briefly in their 2011 paper on patellar tendinopathy. They note there are pros and cons of each approach; eccentric work is often prescribed as a high frequency exercise – with Alfredson’s work recommending 3 x 15 reps of 2 exercises done twice per day. HSR by contrast is usually done 2-3 times per week but in many cases will require access to gym equipment.

HSR involves using high loads – approx. 70-85% of 1RM (1RM – 1 repetition maximum – refers to the maximal weight you can lift once with good technique). Determining 1RM is difficult, especially in patients with pain so it can be approximated. 80% of 1RM is roughly equal to 8RM i.e. the maximal weight you can lift 8 times with good technique.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med. 2013 Apr;43(4):267-86.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Alex Scott, Sean Docking, Bill Vicenzino, Håkan Alfredson, Johannes Zwerver, Kirsten Lundgreen, Oliver Finlay, Noel Pollock, Jill L Cook, Angela Fearon, Craig R Purdam, Alison Hoens, Jonathan D Rees, Thomas J Goetz, Patrik Danielson. Sports and exercise-related tendinopathies: a review of selected topical issues by participants of the second International Scientific Tendinopathy Symposium (ISTS) Vancouver 2012. Br J Sports Med doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092329

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Goon T. Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1. Accessed online at Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1 30 Jan 2016

- ↑ Goon T. Tendinopathy – functional rehab. Accessed online at Tendinopathy – rehab progression – part 1 30 Jan 2016

- ↑ Henriksen M, Aaboe J, Graven-Nielsen T, Bliddal H, Langberg H. Motor responses to experimental Achilles tendon pain. Br J Sports Med. 2011 Apr;45(5):393-8.

- ↑ Ebonie Rio, Dawson Kidgell, Craig Purdam, Jamie Gaida, G Lorimer Moseley, Alan J Pearce, Jill Cook. Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1277–1283.

- ↑ Mathijs van Arka, Jill L. Cookb, Sean I. Dockingb, Johannes Zwervera, James E. Gaidab, Inge van den Akker-Scheeka, Ebonie Riob. Do isometric and isotonic exercise programs reduce pain in athletes with patellar tendinopathy in-season? A randomised clinical trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, available online 7 December 2015

- ↑ J L Cook, C R Purdam. The challenge of managing tendinopathy in competing athletes. Cook JL, Purdam CR. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:506-509

- ↑ Håkan Alfredson, Tom Pietilä, Per Jonsson and Ronny Lorentzon. Heavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For the Treatment of Chronic Achilles Tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 1998 26: 360

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gaida JE1, Cook J. Treatment options for patellar tendinopathy: critical review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011 Sep-Oct;10(5):255-70.