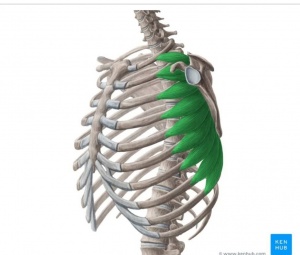

Serratus Anterior

Original Editor - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Kholoud Abd Elghany, Kim Jackson, Joao Costa, Lilian Ashraf, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher and Oyemi SilloIntroduction[edit | edit source]

The serratus anterior is a fan-shaped muscle that originates on the superolateral surfaces of the first to eighth or ninth ribs at the lateral wall of the thorax and inserts along the superior angle, medial border, and inferior angle of the scapula. Its main part lies deep under the scapula and the pectoral muscles.[1]

- It acts on the scapula and is the prime mover in both scapular protraction and scapular upward rotation.

- Is a key scapular stabilizer, keeping the shoulder blades against the ribcage when at rest and during movement.[2].

Image 1: Serratus Anterior.

Watch this comprehensive Kenhub 3 minute video

Origin[edit | edit source]

It originates on the top lateral surface of the eight or nine upper ribs. [3] It then wraps posteromedially around the ribcage, passing beneath the scapula to insert on the underside of the scapula on its medial border.

As the muscle extends from the ribs, it is divided by tendinous septa into nine finger-like groupings of muscle fibers called “digitations.”

- The fibers run obliquely (to varying degrees) between these septa, forming a multipennate muscle architecture.

- Upper three digitations are termed the superior fibers , lower six digitations are termed the inferior fibers.

- The lowest four digitations of the serratus anterior interdigitate with the fibers of the external oblique.

Image 2: The anterior part of the lower fibers are visible on the persons with low body fat percentages

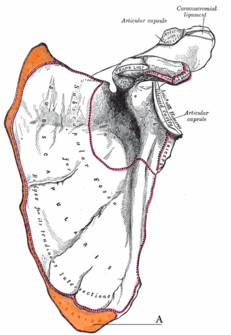

Insertion[edit | edit source]

It inserts on the front border of the scapula.[3] The muscle is divided into three parts :

- Upper / Superior : 1st to 2nd rib → superior angle of scapula.

- Middle / Intermedius : 2nd to 3rd rib → medial border of scapula.

- Lower / Inferior : 4th to 9th rib → medial border and inferior angle of scapula. It is the most powerful and prominent part.[4]

Image 3: Insertional area of SA on scapula.

Nerve and Blood Supply[edit | edit source]

- The long thoracic nerve, which arises from C5 to C7 nerve roots of the brachial plexus.[1]

- Lateral thoracic artery, the superior thoracic artery and the thoracodorsal artery.[1]

Function[edit | edit source]

The main actions are protraction and upward rotation of the scapulothoracic joint.[5]

It’s also a key scapular stabilizer, keeping the shoulder blades against the ribcage when at rest and during movement. It also acts with the upper and lower fibers of the trapezius muscle to sustain upward rotation of the scapula, which allows for overhead arm movement[1]. See Dynamic Stabilisers of the Shoulder Complex and Scapulohumeral Rhythm.

When the shoulder blade is in fixed position the accessory inspiratory muscles (used in respiratory distress) are activated e.g breathing after a sprint, person with emphysema. The serratus anterior lifts the ribcage and thus supports breathing.[4]The other accessory inspiratory muscles include sternocleidomastoid, scalene muscles, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, trapezius, latissimus dorsi, erector spinae, iliocostalis lumborum, quadratus lumborum[6]

Image 4: The serratus anterior is also known as the “boxer’s muscle,” as it is largely responsible for the protraction of the scapula which occurs when throwing a punch.

Clinical Relevance[edit | edit source]

Scapular Winging[edit | edit source]

Dysfunction of the serratus anterior muscle is from the causes of scapular winging. Weakness of the serrratus anterior muscle, leads to the unopposed action of the glenohumeral abductors which result in scapula downwards rotation, inwards rotation and anterior tilt during shoulder abduction and flexion. If this position is maintained it’d lead to adaptive shortening of the pectoralis minor muscle resulting in more scapular anterior tilt and inwards rotation. Explaining the scapular “winging” posture associated with weak serratus anterior.[7]

The most common cause of scapular winging is injury to the long thoracic nerve, leading to serratus anterior palsy. The long thoracic nerve descends across the lateral thoracic wall, making it susceptible to injury during anterolateral thorax surgeries . Other causes of isolated serratus anteiro palsy are traumas, strenrous work, athletics, anesthesia, infection and idiopathic causes. Neuropraxia of the long thoracic nerve could result from compression or stretch injuries.

Muscular avulsion of the serratus anterior muscle is from the less recognized causes of scapular winging.[8]

Subacromial Impingement[edit | edit source]

Weakness of the serratus anterior leads to altered line of pull of the rotator cuff muscle which could increase the risk of subacromial impingement syndrome.

Also, serratus anterior is needed for scapula upward rotation. posterior tilt and, to a lesser extent, external rotation of the scapula which may increase or maintain the volume of the subacromial space reducing the likelihood of subacromial impingement.[7]

Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome (SAMPS) And Trigger Points[edit | edit source]

Chronic chest pain of noncardiac origin is a heterogeneous disorder, and myofascial pain syndrome is often an overlooked cause that can affect a single muscle or several functional muscle units; it is characterized by taut bands, commonly described as trigger points. The syndrome includes a constellation of symptoms one of which is pain overlying the fifth to seventh ribs in the midaxillary line. Referred pain may radiate toward the anterior chest wall, the medial aspect of the arm, and finally, toward the ring and little finger on the ipsilateral side . The pain of SAMPS can be intermittent or constant. The serratus mainly contributes to :

- Pain between shoulder blades

- Golfers elbow pain

- Rib pain

- Arm pain[9]

Differential Diagnosis

Intercostal Nerve Neuralgia

It can be differentiated through palpation. In SAMPS , palpation of trigger points will produce the pain that occurs spontaneously. In intercostal neuralgia , palpation will not produce pain or referred pain because the pain of intercostal neuralgia is situated along a dermatome.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

The serratus anterior muscle is very thin and covers the side of the ribcage.

- You can feel it by putting your hand just below the arm pit.

- It also helps to experience how your ribs feel, so that you can distinguish the ribs and this thin and superficial muscle.

- To do so, just feel the first ribs under your nipple.

- Now you will be able to distinguish the muscle from the ribs.

Muscle Test[edit | edit source]

The 3 tests below can be used to examine the serratus anterior muscle weakness and scapula winging

- Serratus Anterior Strength Test or Push Out Test is used to examine the serratus anterior muscle weakness and scapula winging. [10]

- Shoulder abduction test. Therapist applies a downwards resisting force against the scapular plane abduction of the shoulder at about 120–130° and against upward rotation of the scapula. A weak serratus anterior would result in the patient failing to resist the therapist’s force resulting in the shoulder breaking into adduction and the scapula can't rotate upwards significantly. [7]

- In the third test the patient is in a seated or supine position, with his arm flexed 90-100 degrees and his elbow fully extended. The therapist resists the maximally protracting force by the patient. In case of serratus anterior muscle weakness the patient’s scapula is pushed into a retracted and internally rotated position leading to scapular winging appearance.[7]See video below.

Exercises for Activating Serratus Anterior[edit | edit source]

Dynamic hug

Serratus anterior punch

Wall slide tasks[7]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, thorax, serratus anterior muscles. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531457/ (accessed 9.1.2022)

- ↑ King of the gym Serratus anterior Available:https://www.kingofthegym.com/serratus-anterior/ (accessed 9.1.2022)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://www.healthline.com/human-body-maps/serratus-anterior-muscle#2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M. Schünke/E. Schulte/U. Schumacher: Prometheus – LernAtlas der Anatomie – Allgemeine Anatomie und Bewegungssystem, 2.Auflage, Thieme Verlag (2007), S.294-295 J. E. Muscolino: The muscular system manual – The skeletal muscles of the human body, 2.Auflage, Elsevier Mosby (2005), S.214-217 P. Berlit: Klinische Neurologie, 3.Auflage, Springer Verlag (2011), S.345 [1]

- ↑ Richard D. Gray’s anatomy for students.

- ↑ Ken hub Anatomy of breathing Available:https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/anatomy-of-breathing (accessed 9.1.2022)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Neumann DA, Camargo PR. Kinesiologic considerations for targeting activation of scapulothoracic muscles-part 1: serratus anterior. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2019 Nov 1;23(6):459-66.

- ↑ Didesch JT, Tang P. Anatomy, etiology, and management of scapular winging. The Journal of hand surgery. 2019 Apr 1;44(4):321-30.

- ↑ Calais-German, Blandine. Anatomy of Movement. Seattle: Eastland Press, 1993. Print Davies, Clair, and Davies, Amber. The Trigger Point Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide For Pain Relief. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc., Print Simons, David G., Lois S. Simons, and Janet G. Travell. Travell & Simons’ Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1999. Print. Schünke, Michael., Schulte, Erik, and Schumacher, Udo. Prometheus: Lernatlas der Anatomie. Stuttgart/New York: Georg Thieme Verlag, 2007. Print [2]

- ↑ David J. Magee. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 6th edition. Elsevier. 2014.