Postural Changes Affecting Voice Production: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

* There is a lack of consistency in the literature about which muscles are included in each chains<ref>Rosário JL. Understanding muscular chains – a review for clinical application of chain stretching exercises aimed to correct posture. EC Orthopaedics. 2017;5(6):209-34.</ref> | * There is a lack of consistency in the literature about which muscles are included in each chains<ref>Rosário JL. Understanding muscular chains – a review for clinical application of chain stretching exercises aimed to correct posture. EC Orthopaedics. 2017;5(6):209-34.</ref> | ||

* It is difficult to describe in a reliable way the relationships between body parts that are further apart. It is easier to assess the effect of retractions that are in closer proximity (e.g. neck - shoulder - head - larynx – mandible)<ref name=":0" /> | * It is difficult to describe in a reliable way the relationships between body parts that are further apart. It is easier to assess the effect of retractions that are in closer proximity (e.g. neck - shoulder - head - larynx – mandible)<ref name=":0" /> | ||

== Trauma and the Compensatory Mechanism == | |||

It is possible to understand postural compensation by comparing it to the processes that occur after trauma, such as an ankle sprain.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

=== Acute phase === | |||

* The traumatic event destabilises the system | |||

* There is pain and changes in the motor (e.g. gait) and postural patterns<ref name=":0" /> | |||

=== Post-acute phase === | |||

* Even without pain, postural changes occur during the acute phase | |||

* These changes need to be re-educated in order to avoid alterations in tension in the postural muscle chains<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Forward Head Position == | |||

Abnormal posture of the head at the cervical and scapular level can be associated with several postural anomalies. | |||

* Forward head posture is more pronounced in individuals with shoulder pain (associated with overuse syndrome of shoulders)<ref>Singla D, Veqar Z. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5659804/ Association between forward head, rounded shoulders, and increased thoracic kyphosis: a review of the literature]. ''J Chiropr Med''. 2017;16(3):220-9.</ref> | |||

* Shoulder injury can have a negative influence on neck alignment.<ref>Katsuura Y, Bruce J, Taylor S, Gullota L, Kim HJ. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7076593/#bibr5-2192568218822536 Overlapping, masquerading, and causative cervical spine and shoulder pathology: a systematic review]. ''Global Spine J''. 2020;10(2):195-208. </ref> There can be alterations in trapezius kinematics in patients who have neck pain and shoulder dysfunctions<ref name=":0" /> | |||

* Increasing thoracic kyphosis results in an increased retraction and anterior tilt of the scapula<ref name=":0" /><ref>Ludewig PM, Braman JP. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3010321/ Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation]. ''Man Ther''. 2011;16(1):33-39. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.08.004</ref> | |||

* Increasing thoracic kyphosis has also been associated with decreased posterior tilt of scapula and increased elevation<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | [[Category:Course Pages]] | ||

Revision as of 12:04, 7 June 2021

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There are a number of common postural changes that can affect function, pain and disability levels and voice production.

In older adults, the following postural features are commonly observed:[1]

- Increased thoracic kyphosis

- Reduction in intervertebral disc height

- Loss of bone mass

- Forward head position (i.e. anteposition)

- Retraction of muscle chains

- Reduced elasticity and strength

- Cartilage ossification in the larynx

These postural changes can have a significant impact on speech and swallowing function.[1] Examples include:

- Lordosis of the cervical spine inhibits laryngeal elevation and affects swallowing - postural rehabilitation may be beneficial to manage this[2]

- Ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament can lead to dysphagia - the extent of which is influenced by the thickness of osteophytes, cervical mobility, and cranio-cervical alignment[3]

When specific postural abnormalities are detected, it is important to determine if the client’s posture can be corrected, or if the postural condition is fixed.

Structured Posture[edit | edit source]

Structured posture describes postural disorders where there are underlying morphological abnormalities in the bone / soft tissues. Examples of a structured posture are:[4]

- Idiopathic scoliosis

- Scheuermann juvenile kyphosis

- Congenital vertebral malformation

- Sequels of spine osteomyelitis

- Spondylolisthesis

These conditions are more clinically significant as they are less flexible and can only be modified with difficulty.[1] They require a specific diagnosis and management.[4]

Non-Structured Posture[edit | edit source]

A non-structured posture is modifiable with the help of the therapist.[1] Individuals with non-structured postures may have similar clinical features as those with structural abnormalities.[4] For instance, scheuermann's disease is often mistaken for adolescent postural kyphosis, so it is necessary to differentiate the two conditions based on the physical examination and radiographic analysis.[5]

Antalgic Posture[edit | edit source]

Antalgic postures are technically modifiable but, if corrected, the patient complains of pain.[1]

Compensatory Posture[edit | edit source]

Compensatory postures can be actively and passively corrected, but the patient does not tend to stay in the corrected position. NB If the cause of the compensation is not treated, the postural destabilisation will return in time.[1]

When observing patients, it is important to compare the patient's posture with "normal" posture.

Common Non-Structural Postures[edit | edit source]

Side View[edit | edit source]

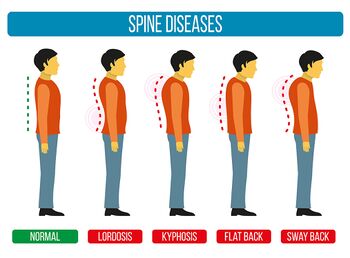

Common postural deformities can be viewed from the side, as is seen in Figure 1.

Lordotic Posture:[4]

- Increased lumbar lordosis

- Increased pelvic anteversion (anterior tilt), which leads to increased hip flexion

- Knees may be hyperextended, which causes plantar flexion at the ankle

- The head line runs posteriorly to the lumbar vertebral bodies, and anteriorly to the knee joint axis

- Increased thoracic

- Head protraction

- Flattened or reversed lower cervical lordosis, with increased upper cervical lordosis

- Protraction of the shoulders

- Pronounced abdomen

- There may be deformation of the rib cage, which can affect inspiration

- There may be anteversion of the pelvis

- There may be cervical osteophytosis (i.e. the formation of bone spurs) and possible stress at the upper part of the oesophagus and dysphagia

- The head line is anteriorly to the thoracic spine, lumbar vertebral bodies, and hip and knee joint axis

- Loss of lumbar lordosis

- Flattened lower part of thoracic kyphosis, but increased upper thoracic region

- Potentially kyphotisation at the cervico-thoracic junction

- There may be a forward head position

- Either neutral pelvis or decreased anterior tilt

- Retraction of the hamstring muscles

- The head line and the base line usually overlap and pass anteriorly to the lumbar vertebral bodies and posterior to the hip joint axis. The head may be shifted anteriorly to the base line.

- Anterior pelvic shift

- Thoracic kyphosis, which extends into the upper lumbar spine

- Shorter lumbar lordosis

- Normal or slightly decreased anterior pelvic tilt

- The dorsal spine is displaced posteriorly while the head and pelvis are anterior to the plumb line

It is possible to observe changes in a client's posture during swallowing, phonation / singing. These changes will provide the therapist with information about patterns and compensatory movements.[1] If active correction is possible, while maintaining the correct posture it is advisable to encourage re-education techniques.[1] If active corrections are not easy or limited, it is advisable to treat the patient with passive manual techniques, elongation of retracted muscle chains and manual therapy.[1]

Posterior View[edit | edit source]

Four specific conditions related to the ascending or descending syndrome can be observed from a posterior view.[1]

Ascending postural syndrome:[1]

- Head and shoulder are in line with the plumb line

- Pelvis is displaced

Descending postural syndrome:[1]

- Head and shoulder are displaced

- Pelvis is central

Mixed ascending and descending postural syndrome:[1]

- The upper part is displaced in one direction and the lower part is displaced to the opposite side

Non-harmonic postural syndrome:[1]

- All sectors (head, shoulders and pelvis) are displaced to the same side

- This is a more common presentation after trauma

Muscle Chains[edit | edit source]

These postural syndromes are caused by abnormalities in muscle or myofascial chains. It is proposed that muscles do not function as independent units, but rather they are part of a "tensegrity-like, body-wide network, with fascial struc- tures acting as linking components.”[6] Muscle chains are the functional anatomical expression of neuromuscular control and they:[1]

- Induce movement

- Facilitate cross movement

- Transmit mechanical tension to the postural system

Because the postural system has to compensate to maintain a static position or to support dynamic movement, muscle chains are part of the proprioceptive system.[1]

Proprioceptors (e.g. muscle spindles, golgi tendon organs) inform the upper control centres about the state of the body (e.g. limb position and movement, sense of tension or force, balance or effort[7]). They facilitate complex movement, but also cause remote compensations.[1]

Limitations:

- There is a lack of consistency in the literature about which muscles are included in each chains[8]

- It is difficult to describe in a reliable way the relationships between body parts that are further apart. It is easier to assess the effect of retractions that are in closer proximity (e.g. neck - shoulder - head - larynx – mandible)[1]

Trauma and the Compensatory Mechanism[edit | edit source]

It is possible to understand postural compensation by comparing it to the processes that occur after trauma, such as an ankle sprain.[1]

Acute phase[edit | edit source]

- The traumatic event destabilises the system

- There is pain and changes in the motor (e.g. gait) and postural patterns[1]

Post-acute phase[edit | edit source]

- Even without pain, postural changes occur during the acute phase

- These changes need to be re-educated in order to avoid alterations in tension in the postural muscle chains[1]

Forward Head Position[edit | edit source]

Abnormal posture of the head at the cervical and scapular level can be associated with several postural anomalies.

- Forward head posture is more pronounced in individuals with shoulder pain (associated with overuse syndrome of shoulders)[9]

- Shoulder injury can have a negative influence on neck alignment.[10] There can be alterations in trapezius kinematics in patients who have neck pain and shoulder dysfunctions[1]

- Increasing thoracic kyphosis results in an increased retraction and anterior tilt of the scapula[1][11]

- Increasing thoracic kyphosis has also been associated with decreased posterior tilt of scapula and increased elevation[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 Banfi M. Postural Principles Useful in Speech Therapy. Physioplus. 2021.

- ↑ Sato K, Chitose SI, Sato K, Sato F, Ono T, Umeno H. Dysphagia precipitated by cervical lordosis in the aged. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020:145561320946644.

- ↑ Nishimura H, Endo K, Aihara T, Murata K, Suzuki H, Matsuoka Y et al. Risk factors of dysphagia in patients with ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2020;28(3):2309499020960564.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Czaprowski D, Stoliński Ł, Tyrakowski M, Kozinoga M, Kotwicki T. Non-structural misalignments of body posture in the sagittal plane. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018;13:6.

- ↑ Horn SR, Poorman GW, Tishelman JC, Bortz CA, Segreto FA, Moon JY et al. Trends in treatment of scheuermann kyphosis: A study of 1,070 cases from 2003 to 2012. Spine Deform. 2019;7(1):100-106.

- ↑ Wilke J, Krause F, Vogt L, Banzer W. What Is evidence-based about myofascial chains: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):454-61.

- ↑ Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1651-97.

- ↑ Rosário JL. Understanding muscular chains – a review for clinical application of chain stretching exercises aimed to correct posture. EC Orthopaedics. 2017;5(6):209-34.

- ↑ Singla D, Veqar Z. Association between forward head, rounded shoulders, and increased thoracic kyphosis: a review of the literature. J Chiropr Med. 2017;16(3):220-9.

- ↑ Katsuura Y, Bruce J, Taylor S, Gullota L, Kim HJ. Overlapping, masquerading, and causative cervical spine and shoulder pathology: a systematic review. Global Spine J. 2020;10(2):195-208.

- ↑ Ludewig PM, Braman JP. Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 2011;16(1):33-39. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.08.004