Positioning

Original Editors - Naomi O'Reilly and Stacey Schiurring

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Stacy Schiurring and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Moving and positioning lie within the broader context of manual handling and is a key aspect of patient care for rehabilitation professionals. Optimum positioning is a good starting point to maximise the benefit of other interventions, such as bed exercises and breathing exercises; it can also assist rest and mobility, thereby facilitating recovery, enhancing function and preventing secondary complications. [1] [2] However, although it is important, it must not be seen in isolation and is just one aspect of patient management where the overall goal is to optimise independence.[3]

In medical terms, ‘position’ relates to body position or posture,[4] thus positioning involves placing the patient into a specific static alignment, which can involve their entire body, or just a single body part or limb, which involves patient handling, transporting or supporting a load (i.e., lifting, lowering, pushing, pulling, carrying or moving) by using hands, bodily force and/or mechanical devices. [5] Positioning can be achieved either;

- actively by the patient, meaning they are able to move under their own volition, or

- passively, where the patient is placed into a specific position with assistance of one or more other persons. [6]

Positioning has the potential to redistribute pressure and shear forces, and subsequently prevent the internal tissue deformation, tissue ischaemia, and irreversible tissue damage that causes pressure injuries[7] but a major challenge to positioning is trying to place a dynamic body into a prolonged static position.[6] The human body was made for movement, it does not tolerate prolonged periods of immobilisation well. This means the positioning must be comfortable and allow the patient to reposition as needed, while maintaining the purpose behind the positioning. It is essential to frequently evaluate the effect that positioning is having on the individual to ensure that the intervention is helping to achieve the desired result or goal. [8] Consider whether the positioning procedure is being clinically effective and, where possible, is evidence based.

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The purpose and indications for therapeutic positioning vary depending on the patient population being treated,[9][10][11][12][13] but is typically indicated for patients who have difficulty moving or require periods of rest when normal function is impaired. Patients should always be encouraged to move themselves where possible, but where assistance is required they should to do as much of the movement as they can themselves.[14]

Comfort and Pain[edit | edit source]

Several studies have investigated the effect of different positioning strategies on patient comfort and pain. Use of pressure-relieving surfaces, such as self-adjusting technology (SAT), air and low-air loss mattresses and alternating pressure mattresses are associated with improved patient comfort in hospital settings. [15] Position change from supine to a semi-seated position in patients after trans-femoral coronary angiography with groin and back pain is effective and safe for reduction of pain without increasing vascular complications. [16] Similarly back pain was also decreased with positioning into standard fowler's position with head of bed elevated to 45–60° without causing any vascular complications following percutaneous coronary intervention. [17]

Postural Alignment for Optimal Function[edit | edit source]

Positioning plays a crucial role in contracture management and postural alignment by maintaining or improving joint range of motion, preventing further contracture development, and promoting functional independence. Regular repositioning, combined with adequate support, can help manage postural alignment and minimise the progression of contractures. Collaborative goal setting and regular re-evaluation of the positioning plan are essential for effective contracture management.[18] Communication and coordination among team members are critical for optimal positioning and contracture management outcomes.[19]

Positioning also plays a crucial role in improving activities of daily living (ADLs), such as swallowing [20][21], vocalisation and speech production[22], and personal hygiene and can enhance functional independence. Swallowing function has been shown to be "both directly and indirectly" related to postures with altered positions of the head, cervical angle, body position combined with anterior cervical muscle tone having a negative impact on swallowing.[23][24] Upright or slightly reclined positions have been shown to facilitate safe swallowing and reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia. [21] In spinal cord injury static splinting begins immediately following injury including resting hand splints for night use in all levels of cervical injuries to maintain range of motion of structures in the hand, while allowing slight shortening of the finger flexors to develop an optimal tenodesis function, providing some grip function in tetraplegia.[25]

Reduce Pressure[edit | edit source]

Routine repositioning has been reported to reduce the odds of hospital-acquired pressure injuries by 14%, while use of repositioning device was associated with a statistically significant reduction in hospital-acquired pressure injuries in Intensive Care, with lower perceived staff exertion with use of the device in comparison to manual positioning.[26] Positioning devices including cushions and pressure-relieving mattresses are also associated with improved offloading and reduced pressure injury incidence. [15] While cushions are seen as the primary device for pressure relief in wheelchair users, [27] backrest shape in wheelchair users may also have a role in maintaining low buttock pressure and good perfusion, with increased backward inclination of the backrest above 120° associated with reduced buttock pressure, highlighting the importance of optimal wheelchair positioning. [28]

Improve Circulation[edit | edit source]

Positioning can be an essential aspect of patient care to improve circulation, reduce oedema, and prevent the development of skin breakdown and pressure injury. Proper positioning strategies aim to elevate and support the limbs to promote blood flow and prevent the accumulation of fluid. Elevation of the leg in patients with venous leg ulcers during sitting enhances venous return and minimises oedema and pain, [29] with greatest benefits seen when the leg is raised above heart level,[30] with leg elevation for 1 h/day significantly associated with prevention of venous ulcer recurrence.[31] In spinal cord injury positioning of the hand in elevation in the acute phase, typically with pillows or slings attached to the bed, assist venous return and reduces arterial hydrostatic pressure to minimise oedema. [32]

Improve Respiration[edit | edit source]

Semi-recumbent with the head of the bed elevated between 30 to 45 degrees and prone positioning improved oxygenation, reduce incidence of hypoxemia, increase lung volume and reduce the incidence of ventilator acquired pneumonia in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation.[33][34][35][36] While there is still research gaps around the effectiveness of lateral positioning to improve oxygenation in ventilated patients without lung pathology or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),[37] there is evidence to suggest that lateral positioning may increase comfort and remove pressure from a pendulous abdomen as in case of pregnancy or obesity haemodynamically stable mechanically ventilated patients.[38][39] Improvement of oxygenation and ventilation may play a role in the promotion of comfort in patients who are mechanically ventilated. [35]

Postural drainage is a positioning technique to mobilise bronchial secretions involving the positioning of a patient with an involved lung segment such that gravity has a maximal effect of facilitating the drainage of broncho-pulmonary secretions from the tracheo-bronchial tree,[40] based on the concept of gravity-assisted mobilisation of secretions to improve respiration.

Improve Sensory Input[edit | edit source]

Adequate arousal and alertness are essential for optimal engagement, participation, and performance in daily activities. Proper positioning can optimise sensory input, increase arousal and enhance engagement in daily activities. Adaptive seating has been shown to significantly improve postural control and stability, leading to enhanced sensory processing.[41] Research suggests that maintaining an upright posture, with appropriate head and trunk alignment, can promote increased alertness.[42]

Improve Mental Health[edit | edit source]

Positioning strategies play a crucial role in promoting mental health and psychological well-being. Positioning assistive devices like standers can improve psychological well-being by promoting autonomy and self-esteem. Research suggests that individuals who use assistive devices experience increased independence and a sense of control over their environment, leading to enhanced self-esteem and overall psychological well-being.[43] Evidence also shows that being in an upright position can enhance alertness, attention, and mood, leading to improved psychological well-being. Supported standing helped individuals with progressive MS feel more like their old selves and provided a sense of normality and enjoyment.[44] Similarly standing frames gave children an opportunity for a change of position, which was seen enjoyable for many reasons, including having a “different view of surroundings,” “being in the upright position,” and “the feeling of being tall.” [45] Overall many positioning devices that promote upright posture also promote social engagement, reduce feelings of isolation, and enhance overall mental health and well-being, with improvements in physical and psychological symptoms often associated with increased participation in activities they valued.[44]

Maintain Dignity and Respect[edit | edit source]

Respecting the dignity of patients is a fundamental principle in healthcare. Patients who are immobilised may feel vulnerable, and dependent. Proper positioning techniques involving the patient and promoting patient involvement can help alleviate these negative emotions and enhance the patient's sense of dignity and self-worth.

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

There are no general contraindications for positioning; however, some positions are contraindicated for specific conditions or situations, most typically seen within hospital settings, particularly in Intensive Care Units or on post surgical wards;[46][47]

| Prone | Trendelenburg | Reverse Trendelenburg |

|---|---|---|

Absolute Contraindication [46]

|

Contraindications

|

Contraindication

|

Relative Contraindication [46]

|

Clinical Considerations[edit | edit source]

Baseline Posture[edit | edit source]

Clinical considerations in patient positioning are crucial for various medical procedures, diagnostic tests, and therapeutic interventions. The baseline posture of a patient can significantly impact these considerations. Posture can be simply defined as the position of the body in space where the body is able to maintain balance during dynamic and static movements, which should provide maximum stability with minimal energy consumption and stress on the body, which is fundamental to any positioning strategy.[4] .Postural assessment is necessary prior to therapeutic positioning taking into consideration abnormal postures including: forward head, kyphosis, lordosis, scoliosis, and pelvic malalignments such as windswept hips.

Sources of Pressure[edit | edit source]

Pressure injuries develop in localised areas when soft tissues are compressed between a bony prominence and an external surface for a prolonged amount of time.[6] Immobility is a major risk factor for development of pressure injuries thus prevention is the best intervention, particularly in patients who have difficulty repositioning themselves. Prioritise positioning to focus on areas of greatest concern.

Orthopaedic Considerations[edit | edit source]

Orthopaedic considerations for patient positioning play a significant role in achieving successful surgical outcomes and minimising complications.

Weightbearing Status; The weightbearing status of a patient can significantly impact the positioning considerations. Patients who are non-weightbearing or restricted from bearing weight on a specific limb may require additional support and stabilisation during positioning. Proper positioning should aim to distribute the patient's weight evenly to maintain stability and prevent excessive strain on unaffected areas.

Total Knee Arthroplasty; In supine, a pillow or roll should not be placed under the surgical knee. Evidence does suggest use of inactive CPM with hip and knee flexion of 30° may mitigate knee swelling and minimise blood loss, leading to early rehabilitation and improved post operative range of motion. [48] [49] Weight bearing through the surgical knee, such as in kneeling, should be avoided until the incision line is well healed and pain controlled.

Total Hip Arthroplasty; Associated movement precautions based on the method of surgical replacement. Traditionally, these precautions stay in place for 6 weeks following the joint replacement, although current evidence does not routinely support the use of these hip precautions in patients post total hip arthroplasty for primary hip osteoarthritis to prevent dislocation.[50]

- Anterior Approach - Avoid hip external rotation, active abduction and flexion beyond 90°

- Posterior Approach - Avoid hip internal rotation, adduction across midline, and flexion beyond 90°

- Lateral Approach - Avoid hip external rotation, active abduction, and extension

Post Amputation; When positioning a person after amputation, several considerations depending on the level and type of amputation, the individual's overall health, and recommendations from healthcare professionals. The residual limb should be aligned in a way that minimises pressure on the incision site, promotes healing, helps manage oedema. To minimise the risk of contractures in Trans-tibial/Below Knee Amputation avoid shortening of hip and knee flexors, while with Trans-femoral/Above Knee Amputation you also need to avoid shortening hip abductors, and external rotation [51]

Sternal Precautions; Following open heart surgery: Avoid shoulder flexion above 90 degrees, shoulder external rotation beyond neutral, and shoulder abduction past 90 degrees. If patient able to reposition themselves, avoid excessive pulling or pushing with their upper limbs and one-sided upper limb activity. [52]

Spinal Precautions: Spinal precautions are guidelines or restrictions put in place to protect the spine and reduce risk of further injury after spinal surgery, spinal trauma, or suspected spinal instability. Restrictions in forward flexion following spinal surgery limit patient's ability to assume certain positions comfortably and may require modifications in their positioning to avoid excessive bending, twisting, or flexion of the spine. Clear communication and understanding of the specific precautions and their impact on positioning are vital to ensure patient safety and optimal outcomes.

External Fixation: An external fixation device is a a bulky and heavy medical device used to stabilise and immobilise bone fractures or other orthopaedic conditions. Depending on the location and purpose of the device, certain movements, positions and weight bearing may be restricted or limited and may limit the patient's ability to move or perform certain activities. Appropriate cushioning, padding, or specialised positioning supports may be necessary to relieve pressure, improve comfort, and prevent skin breakdown. [53]

Neurological Considerations[edit | edit source]

Tone; Spasticity can limit positions secondary to reduced range of motion or tonal fluctuations, while flaccid tone can increase risk of subluxation risk with improper positioning. Splints can support tone management or extremity protection but monitor pressure.

Cognition; Attention, comprehension, and memory, play a crucial role in patient's ability to understand and follow positioning instructions. [54] Consider whether the patient can ,understand the positioning, know when to call for assistance and are safe for a specific position.

Sensation; Directly affects a patient's ability to sense and communicate discomfort or pain. With impaired sensation, may not be able to provide accurate feedback on their comfort level.[55]

Cardiorespiratory Considerations[edit | edit source]

Aspiration Risk; Aspiration is when food, liquid, or some other foreign material enters the airway and lungs. Patients with a known aspiration risk should have the head of the bed elevated to at least 30 - 45 degrees for up to an hour after eating. [56][57] Read more about the relationship between posture and swallowing here.

Pacemaker Precautions; To protect the newly implanted device, which has leads interacting with cardiac tissue are the same for sternal precautions with the additional precaution of limiting reaching behind the patient’s back such as a movement like fastening a bra strap. Read more about precautions after insertion of cardiac implantable electronic devices here.

Circulation Considerations[edit | edit source]

Oedema Management; Typically oedematous limbs will require elevation, ideally above the level of the heart, which should be considered when prioritising other therapeutic positioning interventions. Read more about oedema management here.

Mobility Considerations[edit | edit source]

Mobility plays a significant role in positioning, as it influences a person's ability to independently change positions, move, and maintain stability. It's important to assess an individual's mobility level, consider their specific mobility challenges, to develop a comprehensive positioning plan that promotes mobility, safety, and overall functional independence.

Assistive Devices for Positioning[edit | edit source]

Assistive devices for positioning are tools or equipment designed to assist individuals in achieving optimal body positioning and support for enhanced comfort, function, and independence. These devices are particularly beneficial for individuals with mobility limitations, physical disabilities, or medical conditions that affect their ability to maintain proper posture and positioning.[58] Assistive devices also allow the the healthcare worker to position and move patients in a way that reduces risk for injury to themselves and their patients. Assistive devices that can be utilised for positioning include slide sheets, towels, pillows, cushions, splints, sleep systems, adaptive seating, tilt tables and standing frames.

Read more detail about the wide range of assistive devices available to support patient positioning here.

Overview of Patient Positions[edit | edit source]

| Position | Description | Purpose and Populations | Assistive Devices |

|---|---|---|---|

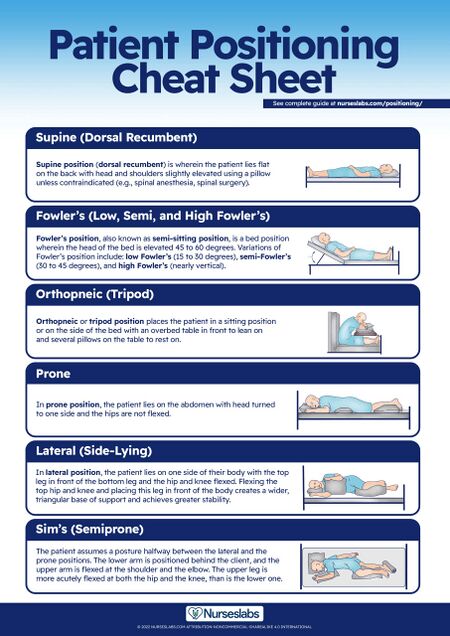

| Supine | Lie on back in anatomical position.

Head and shoulders can be slightly elevated with pillow for comfort, unless contraindicated. Figure.1 Supine Position [59] |

|

|

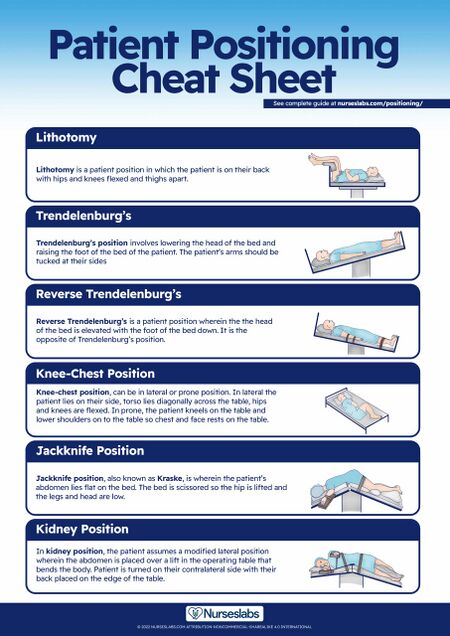

| Trendelenburg Position | Lower head of bed and elevate foot of bed or tilt table with arms by side. |

|

|

| Reverse Trendelenburg Position | Elevate head of bed and lower foot of bed or tilt table with arms by side. |

| |

| Lateral or Side Lying Position | Lie on one side with the top leg in front of the bottom leg with hip and knee flexed.

|

|

|

| Sim's or Semi-prone Position | Lie halfway between side lying and prone with lower arm behind and upper arm flexed at the shoulder and elbow.

The upper leg is more acutely flexed at the hip and the knee than the lower leg. Figure.3 Sim's Position [59] |

|

|

| Prone Position | Lie on abdomen with head turned to one side and hips not flexed. Figure.4 Prone Position [59] |

|

|

| Fowler’s Positions

(Semi-sitting or Semi-recumbant) |

Fowler's;

Head of bed elevated to 45° to 60°  Figure.5 Fowler's Position [59] |

|

|

| High Fowler's;

Head of bed almost vertical | |||

Semi-Fowler’s;

Head of bed elevated to 30° to 45 ° Figure.6 Semi Fowler's Position [59] | |||

| Low Fowler’s;

Head of bed elevated to 15° to 30° | |||

| Standing | Body held in erect position. Shoulders, hips and feet aligned with weight supported by the feet. |

|

|

Principles of Positioning[edit | edit source]

The following principles guiding positioning should be considered in relation to the short‐ and long‐term goals of rehabilitation and management for each specific patient.

Individualised Assessment: Each patient has unique needs and preferences. Conducting an individualised assessment, considering patient's medical condition, mobility limitations, and comfort preferences, is essential for providing dignified and respectful positioning care.

- Define the patient’s functional impairments and abilities as related to positioning.

- Does the patient have appropriate muscle length to comfortably maintain the desired position?

- Does the patient have the cognitive ability to safety remain in the position?

- Can the patient tolerate the position due to cardiopulmonary needs?

- Identify Risk Factors from Proposed Positioning

- Including impaired sensation, sources of pressure or skin tears, risk of falls, increase in pain, or patient safety awareness.

- Determine how much support and level of assistance your patient requires for positioning?

- Independent;

- Patient is able to re-position independently and safely.

- Supervision:

- Patient requires no physical assistance but may require verbal reminders

- Minimal Assistance:

- Patient is cooperative and reliable but needs some minimal physical assistance with positioning,

- Is able to perform 75% of the required activity on their own.

- Typically requires only one person.

- Moderate Assistance

- Patient requires moderate physical assistance

- Is able to perform 50% of the required activity on their own

- Typically requires two people

- May require equipment to assist with positioning.

- Maximal Assistance

- Patient requires full physical assistance for re-positioning

- Is able to perform 0-25% of the required activity on their own

- May be unpredictable and uncooperative

- Requires equipment to assist with positioning

- Independent;

- Reassessment after each positioning intervention

- Did the positioning achieve the desired result?

- Were there any negative outcomes? e.g. development of pressure areas

Regular Repositioning: Patients should be repositioned frequently to relieve pressure and promote blood circulation. Implementing a repositioning schedule based on the patient's tolerance and healthcare guidelines helps maintain dignity while preventing complications.

Determine Purpose for the Positioning:Why is this positioning being used with this patient? Is it for accurate examination performance, to achieve a specific therapeutic effect or as a preventive measure?

Collaboration and Communication: Engaging patients in the positioning process by seeking their input and involving them in decision-making empowers them and promotes respect. Clear and compassionate communication enhances patient's understanding, cooperation and tolerance of positioning.

Adequate Support and Equipment: Utilising appropriate support surfaces (e.g., pressure-reducing mattresses, cushions) and assistive devices (e.g., bed rails, pillows) ensures proper alignment, comfort, and safety during positioning manoeuvres.

Body Mechanics: Observe good body mechanics and follow moving and handling principles for your and your patient’s safety.

Training and Education: Rehabilitation professionals should receive comprehensive training on proper positioning techniques and share their knowledge as experts on body alignment and mobility with other rehabilitation professionals, their patient and support structures on why the positioning is being used

Document: All positions can be detrimental to the patient if maintained for a long period of time. Document level of assistance required, assistive devices used, any safety precautions taken, especially if the patient is left in a position after your treatment session, for example: patient’s call bell was left in reach, hand-off communication with next treating rehabilitation professional including timeframe for when repositioning is due.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Positioning is a useful multidisciplinary therapeutic tool that can be individualised to a patient’s unique needs and limitations. In summary, evidence-based findings suggest that positioning can significantly impact a patient's comfort and rest. The choice of position should be individualised to the patient's needs and preferences, and the timing and frequency of position changes may be important considerations. Use of pressure-relieving surfaces may further enhance their comfort and prevent pressure ulcers. Through individualised assessments, regular repositioning, collaborative communication, and adequate support, healthcare settings can foster an environment that upholds the principles of dignity and respect. Regular evaluation of the effectiveness of the positioning strategy is essential to ensure that the desired goals are b eing achieved.

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jones M & Gray S (2005) Assistive technology: positioning and mobility. In SK Effgen (Ed) Meeting the Physical Therapy Needs of Children. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company.

- ↑ Pickenbrock H, Ludwig VU, Zapf A, Dressler D. Conventional versus neutral positioning in central neurological disease: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2015 Jan;112(3):35.

- ↑ Chatterton H.J., Pomeroy V.M., & Gratton, J. (2001). Positioning for stroke patients: a survey of physiotherapists aims and practices. Disability and Rehabilitation, 23(10), 413-421.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Carini F, Mazzola M, Fici C, Palmeri S, Messina M, Damiani P, Tomasello G. Posture and posturology, anatomical and physiological profiles: overview and current state of art. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2017;88(1):11.

- ↑ Weiner C, Kalichman L, Ribak J, Alperovitch-Najenson D. Repositioning a passive patient in bed: Choosing an ergonomically advantageous assistive device. Applied ergonomics. 2017 Apr 1;60:22-9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Krug K, Ballhausen RA, Bölter R, Engeser P, Wensing M, Szecsenyi J, Peters-Klimm F. Challenges in supporting lay carers of patients at the end of life: results from focus group discussions with primary healthcare providers. BMC Family Practice. 2018 Dec;19(1):1-9.

- ↑ Gefen A. The future of pressure ulcer prevention is here: detecting and targeting inflammation early. EWMA J. 2018; 19(2): 7- 13.

- ↑ Gillespie BM, Walker RM, Latimer SL, Thalib L, Whitty JA, McInnes E, Chaboyer WP. Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020(6).

- ↑ De Jong L.D., Nieuwboer A., & Aufdemkampe, G. (2006). Contracture preventive positioning of the hemiplegic arm in subacute stroke patients: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 20: 656-667.

- ↑ Davarinos N, Ellanti P, McCoy G. A simple technique for the positioning of a patient with an above knee amputation for an ipsilateral extracapsular hip fracture fixation. Case Reports in Orthopedics. 2013 Dec 12;2013.

- ↑ Inthachom R, Prasertsukdee S, Ryan SE, Kaewkungwal J, Limpaninlachat S. Evaluation of the multidimensional effects of adaptive seating interventions for young children with non-ambulatory cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2021 Oct 3;16(7):780-8.

- ↑ Harvey LA, Glinsky JA, Katalinic OM, Ben M. Contracture management for people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011 Jan 1;28(1):17-20.

- ↑ Salierno F, Rivas ME, Etchandy P, Jarmoluk V, Cozzo D, Mattei M, Buffetti E, Corrotea L, Tamashiro M. Physiotherapeutic procedures for the treatment of contractures in subjects with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Traumatic Brain Injury. InTechOpen. 2014 Feb 19:307-28.

- ↑ McGlinchey M, Walmsley N, Cluckie G. Positioning and pressure care. Management of post-stroke complications. 2015:189-225.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McInnes E, Jammali‐Blasi A, Bell‐Syer SE, Dumville JC, Middleton V, Cullum N. Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015(9).

- ↑ Niknam Sarabi H, Farsi Z, Butler S, Pishgooie AH. Comparison of the effectiveness of position change for patients with pain and vascular complications after transfemoral coronary angiography: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2021 Dec;21:1-0.

- ↑ Mert Boğa S, Öztekin SD. The effect of position change on vital signs, back pain and vascular complications following percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019 Apr;28(7-8):1135-47.

- ↑ Eek MN, Timpka T, Hägglund M. Fracture incidence across pediatric and adolescent cerebral palsy: A longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(9):1545-1551. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.04.016

- ↑ Ryan JM, Schofield G, Jaap A. Effectiveness of physical therapies in the management of musculoskeletal disorders in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(8):787-794. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2020-319286

- ↑ Nakamura K, Nagami S, Kurozumi C, Harayama S, Nakamura M, Ikeno M, et al. Effect of spinal sagittal alignment in sitting posture on swallowing function in healthy adult women: a cross-sectional study. Dysphagia. 2022 Jun 28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Alghadir AH, Zafar H, Al-Eisa ES, Iqbal ZA. Effect of posture on swallowing. African health sciences. 2017 May 23;17(1):133-7.

- ↑ Beukelman D, et al. (2007). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- ↑ Yamazaki Y, Tohara H, Hara K, Nakane A, Wakasugi Y, Yamaguchi K et al. Excessive anterior cervical muscle tone affects hyoid bone kinetics during swallowing in adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1903-10.

- ↑ Jeon YH, Cho KH, Park SJ. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) plus upper cervical spine mobilization on forward head posture and swallowing function in stroke patients with dysphagia. Brain Sci. 2020 Jul 24;10(8):478.

- ↑ Frye SK, Geigle PR. Current US splinting practices for individuals with cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2020 Jun 17;6(1):1-7.

- ↑ Edger M. Effect of a Patient-Repositioning Device in an Intensive Care Unit On Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injury Occurences and Cost. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2017 May 1;44(3):236-40.

- ↑ Black JM, Edsberg LE, Baharestani MM, Langemo D, Goldberg M, McNichol L, Cuddigan J; National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcers: avoidable or unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference. Ostomy Wound Management. 2011, 57(2):24–37.

- ↑ Ukita A, Nishimura S, Kishigami H, Hatta T. backrest shape affects head–neck alignment and seated pressure. Journal of healthcare engineering. 2015 Jan 1;6(2):179-92.

- ↑ Shenoy MM. Prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(3):386–389. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.137824.

- ↑ Collins L, Seraj S. Diagnosis and treatment of venous ulcers. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(8):989–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ↑ Finlayson K, Edwards H, Courtney M. Relationships between preventive activities, psychosocial factors and recurrence of venous leg ulcers: a prospective study. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(10):2180–2190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05653.x

- ↑ Vasudevan SV, Melvin JL. Upper extremity edema control: rationale of the techniques. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 1979;33(8):520-523.

- ↑ Mezidi M, Guérin C. Effects of patient positioning on respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Annals of translational medicine. 2018 Oct;6(19).

- ↑ Coyer FM, Wheeler MK, Wetzig SM, Couchman BA. Nursing care of the mechanically ventilated patient: what does the evidence say? Part two. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23(2):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.08.004. [PubMed: 17074484].

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Bonten MJ. Prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonia: European perspective. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17(4):773–84. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00068-0. [PubMed: 15008598].

- ↑ Cammarota G, Simonte R, De Robertis E. Comfort during non-invasive ventilation. Frontiers in Medicine. 2022 Mar 24;9:874250.

- ↑ Hewitt N, Bucknall T, Faraone NM. Lateral positioning for critically ill adult patients. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016(5).

- ↑ Sanchez D, Smith G, Piper A, Rolls K. Non–Invasive Ventilation Guidelines for Adult Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Agency for clinical innovation NSW government Version 1, Chatswood NSW, ISBN 978-1-74187-954-4 (2014).

- ↑ Thomas PJ, Paratz JD, Lipman J, Stanton WR. Lateral positioning of ventilated intensive care patients: a study of oxygenation, respiratory mechanics, hemodynamics, and adverse events. Heart Lung. 2007;36(4):277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.10.008. [PubMed: 17628197].

- ↑ West MP. Postural Drainage. Acute Care Handbook for Physical Therapists. 2013 Sep 27:467.

- ↑ Brown, T., Leo, G., Austin, D., Moller, A., & Wallen, M. (2017). Effects of adaptive seating devices on the classroom behavior of students with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(3), 1-9.

- ↑ Ryan SE. Lessons learned from studying the functional impact of adaptive seating interventions for children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2016 Mar;58:78-82.

- ↑ Marasinghe KM, Chaurasia A, Adil M, Liu QY, Nur TI, Oremus M. The impact of assistive devices on community-dwelling older adults and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC geriatrics. 2022 Dec;22(1):1-0.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Dennett R, Hendrie W, Jarrett L, Creanor S, Barton A, Hawton A, Freeman JA. “I’m in a very good frame of mind”: a qualitative exploration of the experience of standing frame use in people with progressive multiple sclerosis. BMJ open. 2020 Oct 1;10(10):e037680.

- ↑ Goodwin J, Lecouturier J, Crombie S, Smith J, Basu A, Colver A, Kolehmainen N, Parr JR, Howel D, McColl E, Roberts A. Understanding frames: A qualitative study of young people's experiences of using standing frames as part of postural management for cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development. 2018 Mar;44(2):203-11.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Guérin C, Albert RK, Beitler J, Gattinoni L, Jaber S, Marini JJ, Munshi L, Papazian L, Pesenti A, Vieillard-Baron A, Mancebo J. Prone position in ARDS patients: why, when, how and for whom. Intensive care medicine. 2020 Dec;46:2385-96.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2159.

- ↑ Fu X, Tian P, Li ZJ, Sun XL, Ma XL. Postoperative leg position following total knee arthroplasty influences blood loss and range of motion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2016 Apr 2;32(4):771-8.

- ↑ Li B, Wen Y, Liu D, Tian L. The effect of knee position on blood loss and range of motion following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2012 Mar;20:594-9.

- ↑ Korfitsen CB, Mikkelsen LR, Mikkelsen ML, Rohde JF, Holm PM, Tarp S, Carlsen HH, Birkefoss K, Jakobsen T, Poulsen E, Leonhardt JS. Hip precautions after posterior-approach total hip arthroplasty among patients with primary hip osteoarthritis do not influence early recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies with 8,835 patients. Acta Orthopaedica. 2023 Apr 5;94:141-51.

- ↑ O'Sullivan at.al, Physical Rehabilitation, Chapter 22 “Amputation”. Edition 6

- ↑ Cahalin LP, LaPier TK, Shaw DK. Sternal precautions: is it time for change? Precautions versus restrictions–a review of literature and recommendations for revision. Cardiopulmonary physical therapy journal. 2011 Mar;22(1):5.

- ↑ Hadeed A, Werntz RL, Varacallo M. External Fixation Principles and Overview. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2022. PMID: 31613474.

- ↑ Reference: Gitlin, L. N., & Hodgson, N. (2015). Caregivers as environmental managers in long-term care facilities: Implications for dementia care. The Gerontologist, 55(Suppl 1), S67-S79. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv019

- ↑ Pottecher, T., Heitz, C., & Bruder, N. (2017). Neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury: Report of 206 patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(6), 981-987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.014

- ↑ Kollmeier BR, Keenaghan M. Aspiration Risk. [Updated 2023 Mar 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470169/

- ↑ Schallom M, Dykeman B, Metheny N, Kirby J, Pierce J. Head-of-bed elevation and early outcomes of gastric reflux, aspiration and pressure ulcers: a feasibility study. American Journal of Critical Care. 2015 Jan;24(1):57-66.

- ↑ WHO. Definition of Assistive Technology. Available from: http://www.who.int/disabilities/technology/en/. (accessed19 April 2023)

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 59.5 Rees Doyle, G and McCutcheon, JA, Chapter 3. Safe Patient Handling, Positioning, and Transfers. In: BCcampus Open Education - Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care. Online, Available from: https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/3-4-positioning-a-patient-in-bed/ [Accessed 18/06/2023].

- ↑ Nurseslabs. Patient Positioning: Complete Guide and Cheat Sheet for Nurses. Available from: https://nurseslabs.com/patient-positioning/ (Accessed 18/June/2023)

- ↑ Nurseslabs. Patient Positioning Cheat Sheet Guide P1. Available from: https://nurseslabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Patient-Positioning-Cheat-Sheet-Guide-P2-Nurseslabs.jpg-scaled.jpg (accessed 2 May 2023).

- ↑ Nurseslabs. Patient Positioning Cheat Sheet Guide P1. Available from: https://nurseslabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Patient-Positioning-Cheat-Sheet-Guide-P1-Nurseslabs.jpg-scaled.jpg (accessed 2 May 2023).