Physiotherapy management strategies in people with schizophrenia

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Amber McNeill, Amy Westley, Emma Moisey, Fiona Bartholomew, Sally Phimister, Rucha Gadgil, Kim Jackson, Jane Hislop, Claire Knott, Amanda Ager, 127.0.0.1, Admin and WikiSysop

What is Schizophrenia?[edit | edit source]

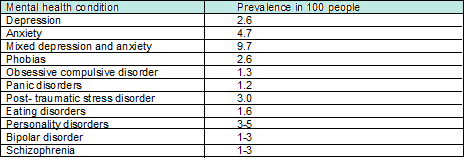

There are many different mental health conditions. The prevalence (the number of people with a given diagnosis at any one time) of some of these is shown below[1][2]:

Schizophrenia is described as a mental health disorder which causes people to interpret reality abnormally through altered emotions, thinking and behaviour. Its cause is thought to be a mixture of genetic, neurobiological (excessive dopamine levels) and environmental factors. However, its true cause has never been established [3] [4].

Facts:

- Schizopohrenia affects more than 21 million people worldwide [4]

- Most people diagnosed with this condition are between the ages of 18 and 35 with men being diagnosed earlier.[5]

- Schizophrenia is more prevalent in men[6].

- Suicide rate amoungst this population is 25-50%[6] .

- 1 in 2 people living with the condition do not receive the care they need [4].

- It has a high incidence of relapse making it a difficult condition to live with and treat [7].

- 1 in 5 people with schizophrenia recover completely and 3 out of 5 people will be helped or get better with treatment.[8]

Schizophrenia is a major public health problem and a leading cause of suffering and disability. The extent to which the condition affects people is variable.[9]

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

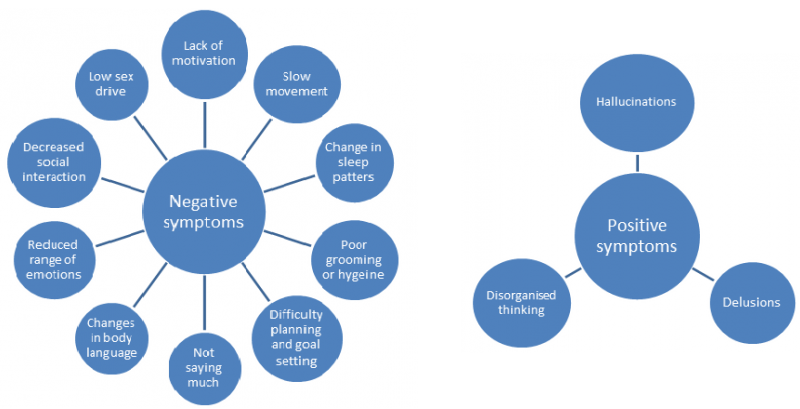

This condition has both ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ symptoms[10]. The concept of positive and negative symptoms of mental health has been around for a long time but was first applied to schizophrenia in the 1970’s to support the differing types of psychopathological manifestations.[9] The positive symptoms are thinking or behaviours that the person with schizophrenia did not have before they became ill and so can be thought of as being added to their mental state. Whereas, negative symptoms describe thoughts or behaviours that the person used to have before they became ill but now no longer have or have to a lesser extent; thus have been lost or taken away from their mental state.[11] In many cases, negative symtoms are present before the onset of positive symptoms which can be seen in the psychotic phase.[9]

The terms positive and negative are widely used in the literature when referring to schizophrenia and will therefore be referenced to throughtout this wiki. The figures below illustrate these symptoms:

The symptoms of schizophrenia affect the person holistically. It is important that these bio-psychosocial issues are understood by physiotherapists as they will impact on interaction and management of this patient group in terms of adopting different communication and treatment styles.

Poor Physical Health in People with Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

It is well documented in the literature that people with schizophrenia have much poorer physical health than the general population. Despite having more contact with health services they have a much poorer life expectancy, dying on average 15-20 years earlier.[12] A key factor associated with poor physical health in this population is the high rate of physical inactivity and tendency to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle than the general population. [13][14][15]

In general, physical inactivity is associated with an array of health risks and is said to be one of the leading causes of long term and secondary conditions such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, obesity and different types of cancers. [16][17] It is important to remember that the same health risks apply to people with schizophrenia but due to the nature of their condition and other influencing factors the risk is much greater[18].

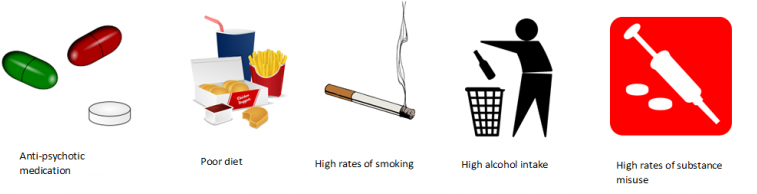

So what other factors could influence the physical health of people with schizophrenia?[19][20][21]

In people with schizophrenia, these factors, combined with physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles significantly increase the risk of developing long term conditions compared to the general population.

Facts:

People with schizophrenia are:

- 1.5-2 times more likely to be overweight[21][22]

- Have a 2 fold increased risk of developing coronary heart disease[23][24]

- Have a 2-fold increased risk of developing diabetes and high blood pressure[21][25]

- Have an increased risk of developing long term lung conditions e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[26]

- Have an increased risk of developing cancers (which they are 50% less likely to survive)[23][27]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Patients with mental health conditions often require medications to live life normally. Every year, in the UK, 2.75 million people go to the GP for help with a mental health condition which accounts for one in four GP consultations[28]. Schizophrenia can require 1.5-3% of spending of a national health budget [29]. For every £1 spent on early intervention, £18 is saved in future spending[30].

The main medications used in schizophrenia are antipsychotics and tranquilizers. Physiotherapists need to be able to understand the effects these drugs will have on the patient's ability to interact with physical management. During an assessment or treatment session a physiotherapist also needs to be aware of how these medications will affect cognition. In relation to this Guo et al. [31]have found that loss of brain volume in patients with schizophrenia is due to the medications they take and this has a subsequent impact on their cognition. Proprioception and the patients’ body image may also be affected due to medications. [32].

This table explains the drugs that are prescribed for patients with schizophrenia. However, they may also be prescribed other medications, for other related issues, which will be discussed in the next section. First generation drugs are prescribed initially, if these do not work second generation drugs are tried and so on.

| First Generation Drugs (FGA) | Haloperidol, Chlorpromazine Hydrochloride |

| Second Generation Drugs (SGA) | Olanzipine, Quetapine, Risperidone. |

| Thirds generation Drugs (TGA) | Aripiprazole (agonist of dopamine receptors) |

It is important to recognise that patients will have different reactions to medications and therefore may experience side-effects to varying severity. FGA side effects are involuntary. Some experience akathisia and dystonia which are sometimes misdiagnosed as aggression .[33]

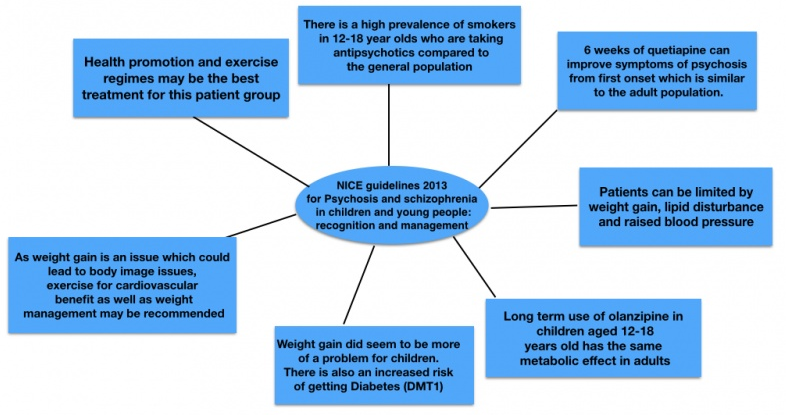

For further reading, the NICE guidelines[34]for Psychosis and Schizophrenia discuss which medications should be chosen and when. You can find this from section 1.3.5 and onwards.

The Side Effects of Schizophrenia Medication and Considerations for Physiotherapists[edit | edit source]

It should be noted that you may come across people with other mental health conditions who are experiencing similar side effects as they may be taking some of the same medications.[35]

It has been reported that 68-90% of individuals with schizophrenia do not adhere to their medication programmes because of the common reported side effects.[35][36]This can make symptoms worse leading to functional problems.

The main side effects of schizophrenia medications are:

- Weight gain,

- Impotence,

- Insomnia,

- Cognitive impairment

- Chronic sedation and

- Lack of ability to concentrate in activities of daily living. [37][35][32]

The SIGN Guidelines [37] for Management of Schizophrenia suggest that to help medication-related weight gain, lifestyle changes should be taken. A physiotherapist can help with designing an effective exercise programme that helps reduce weight. There is a high level of evidence for non-adherence to medication for patients with schizophrenia. The SIGN Guidelines [37] recommend that all medication choices should be discussed with the patient before any decisions are made.

There have been a lot of studies about non-adherence. This is a major problem in this population, as patients who are not adherent to their medication are more likely to relapse, be readmitted to hospital and have a longer hospital stay[38].

A study by Schirmer et al. [39] found that conducting patient education sessions about medication by medical staff was effective in increasing adherence, such that patients continued to take their medication after discharge. In the intervention group 98% took their correct doses compared to the control group at 78%. This may be an area that physiotherapists can take part in as explaining why the medication is important for their wellbeing it may help with adherence. As physiotherapists are not experts in medication all advice given should be in line with what the prescribing medical staff recommend.

For patients with schizophrenia, cognitive impairment can make functional rehabilitation more difficult. Patients find having meaningful relationships, keeping employment and living independently difficult due to their impaired cognition[40]. Michalopalou et al.[41] conducted a systematic review of studies that have trialled medication and cognitive remediation. However, it is not clear if the effects of the drugs are maintained after the course has been completed. This means that there might not be a translation of the drug effects to functional ability. This paper [41] recommends cognitive behavioural therapy and medication as the best way to manage cognitive impairment. Interestingly, it was also found that physical activity can have effect on the plasticity of neural tissue, by affecting serotonin release. Could this indicate a need for further research in this area?

Other considerations

Smoking status affects how medication works for patients. If patients smoke they experience problems with their memory. There is an obvious health risk for patients who smoke, but this paper found that there is an added risk for patients with schizophrenia and how their medication works [42].

Poor physical health and low socio-economic position are associated with poor mental health. Physical activity has been linked to a reduced use of psychotropic medications in middle aged men and women [43]. Personally tailored exercise regimes are important because every patient is unique and will have different side effects from their medication[44]. Some patients with schizophrenia find it difficult to recognise their bodies and some have proprioception issues. It can sometimes be related to the medication, but as schizophrenia is a neurological disorder patients have a physiological reason for proprioception issues [45]. All of these issues will be covered in the sections below in more detail.

A physiotherapist's role may not be physical when it comes to medication adherence. As discussed above using verbal encouragement could improve medication compliance allowing patients to get the most out of physiotherapy sessions[46]. Some may argue it is not a physiotherapist’s place to tell patients to take medication. However, as health professionals we have a duty of care to our patients[47]. Patients can also use self reported questionnaires, such as the Glasgow antipsychotic side effect scale, to let health professionals know how their medication is affecting their daily life. These questionnaires can improve effective communication between the patient and their health care provider including the physiotherapist. [48] It can also highlight problems that need to be adressed by doctors, for example in out patients a patient with schizophrenia may have more contact with a physiotherapist.

Physiotherapy Management Approaches in People with Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

Health Promotion[edit | edit source]

In general, the key role of physiotherapists and principle of physiotherapy is to ‘help restore movement and function when someone is affected by injury, illness or disability’[49]. As described earlier however, it is now recognised that physiotherapists are perfectly positioned to link mind and body.[50] A recent publication by CSP Scotland [51] suggests that the key role of physiotherapy in mental health is to improve the well-being of people with physical impairment associated with mental illness and improve their psychological health through a range of approaches.

If we look more specifically at schizophrenia, we already know that this population have very poor physical health and this is a major contributor to the significantly lower life-expectancy than the general population[52]. Despite this, many of the factors that contribute to the poor physical health in this population are said to be ‘modifiable’ i.e. they can be changed and it appears that physiotherapists are key to this process.[53]

A recent article by Kaur et al. [53]suggested that simple lifestyle modifications can result in improved health and quality of life in individuals with mental illness. When managing individuals with schizophrenia, health promotion is vital. This is “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health”. One of the main ways that physiotherapists promote health is by encouraging physical activity. The CSP believes that physiotherapists have a key role in “enabling physical activity for health promotion, disease prevention and relapse”.

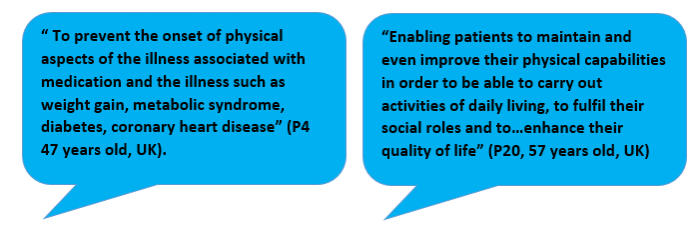

A cross-sectional qualitative study by Stubbs et al.[15]looking at physiotherapists’ perspectives of their role in managing patients with schizophrenia also identified physical activity as one of the most important ways to promote health. A couple of participant responses relating to the role in health promotion and physical activity can be seen below.

This is the first international study of its type and it surveyed 115 physiotherapists from 31 countries. Although the exact response rate is unknown and there is a high risk of social desirability in the responses, some important themes emerged.

43.5% of respondents believed that physiotherapists should lead in the promotion of physical activity and structured exercise in people with schizophrenia. Encouraging people to live a healthier lifestyle was also identified as a key role as health promotion could help in the management of the various long-term conditions that arise[15]. Encouraging people to be more active has the potential to improve the physical health of people with schizophrenia whilst also having a positive influence on their mental health and social functioning [53].

As part of health promotion, as a health professional, it is within our duty of care to sign post/ refer an individual to other services e.g. weight management clinics, smoking cessation and addiction services, when needed. NICE Guidelines for Schizophrenia and Psychosis in Adults[54] state that people with schizophrenia should be offered help to stop smoking even if previous attempts have been unsuccessful. Although physical activity is the main focus in this section of the wiki, it is important to be aware of the other ways we, as physiotherapists could influence an individuals health.

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

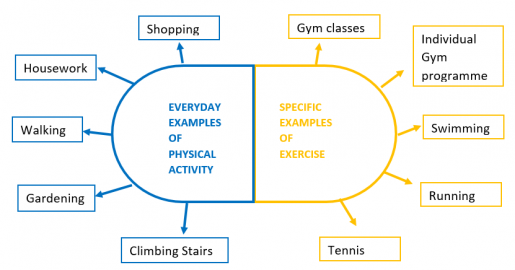

Before exploring this topic in direct relation to schizophrenia, it is important to firstly understand what it means. Physical activity and exercise are often used synonymously however they do have slightly different meanings and it is important to be aware of the difference.

Physical activity is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure”[55]. Exercise on the other hand is simply a specific type/form of physical activity which is said to be planned, structured and purposeful[56].

People often think that to be physically active you have to go to the gym. The key thing to note is that physical activity can take any form and even simple everyday tasks constitute to being physically active. Some examples of everyday tasks and specific types of exercise can be seen below.

Recommendations have been created as a guide to the amount and level of physical activity that the general population should be engaging in. Please take time to familiarise yourself with these recommendations.[57][81][112][112][112]

Specific exercise often requires higher rates of energy expenditure than simple everyday examples of physical activity. Where exercise intensities are higher, the health benefits are said to be greater[58]. Despite this, it is important to remember that people with schizophrenia are often very sedentary and have very low levels of physical activity engagement.[13] This means that when promoting physical activity you have to remember to start small and gradually build up. Finding everyday tasks that an individual can enjoy e.g. gardening or walking the dog may in fact be far more beneficial to that person than trying to get them to go to the gym or out for a run. Remember, each person will be different.

Please take time to watch this video which was produced by MIND[59] . It gives some simple advice to individuals who have a mental health condition and are trying to become physically active however the information is also very useful to know from a physiotherapy perspective.

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Promoting physical activity is a recurring feature in the news and across social media. If people were engaging in enough physical activity then there would be less need to promote it – as such it is important to know what factors prevent people from being physically active.

As this wiki is focused on schizophrenia, it will look to explore the factors that could affect their engagement in physical activity. Due to spending large periods of their time being sedentary, the majority of people with schizophrenia fail to meet the physical activity recommendations of 30 minutes per day [12]. As final year physiotherapy students and newly qualified physiotherapists it is vital to know about the barriers and challenges you may face when trying to promote physical activity in people with schizophrenia and how they may influence your practice.

After reviewing the existing literature, the barriers to engaging in physical activity in people with schizophrenia could be grouped into 3 main categories. They are:

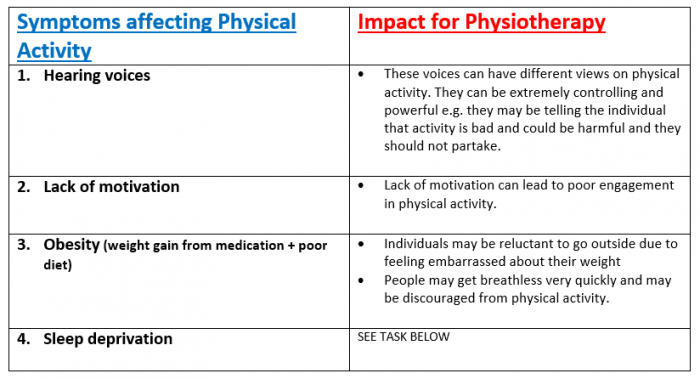

1. Symptoms as Barriers:

The symptoms of schizophrenia and side effects from medication are a major contributor to physical inactivity in this population. The table below highlights these barriers and the impact that they can have on physiotherapy management.[60][61][62][59]

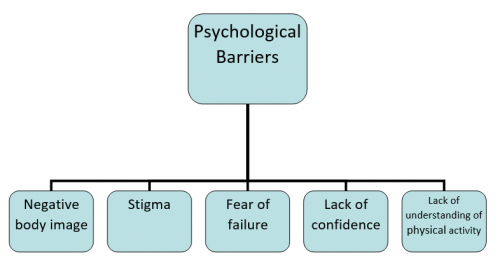

2. Psychological Barriers

Psychological barriers are internal thoughts, feelings or beliefs that an individual has which cause them to feel they cannot do something or cannot complete a task.[63] Below are a number of common psychological barriers identified in the literature relating to people with schizophrenia. Each barrier is explained and the potential impact on physiotherapy management discussed.

3. Social/Environmental Barriers

A number of social and environmental factors have been identified as barriers to physical activity in people with schizophrenia.

Lack of time

Not having enough time to engage in physical activity is a common barrier to physical activity participation in people with schizophrenia, and many other mental health conditions [59][61]. It is important that as physiotherapists we work with the individual to establish ways in which physical activity could be incorporated into their everyday life.

Lack of Income

On the whole, employment rates in people with mental health conditions are lower than the general population [64]. In the schizophrenic population, where individuals had jobs, participation in physical activity was higher as people had the money to pay for gym memberships or exercise classes.[61] There are safeguards in government policy to help people with mental health conditions to get back to work. Access to work[65][65][17][24][./Physiotherapy_management_strategies_in_people_with_schizophrenia#cite_note-access_to_work-24 [24]][24] helps those who have had to take time out due to a mental health condition get back into a career or training. This was helped by the Equality Act of 2010.[66] and the Mental health Act of 1983 [67]. Under this act employers cannot discriminate against those who have mental health conditions. Physiotherapists may need to help prepare people with schizophrenia for work through vocational rehabilitation. Other factors including, spending money on cigarettes, alcohol and unhealthy foods also contributed to the lack of finances available to engage in physical activity[61]. A possible solution for this from a physiotherapy point of view is to find activities that the individual is able to perform without having to pay for them e.g. walking or home exercise programmes.

The Environment

Due to lack of income, people with schizophrenia often live in poorer areas of the community[68]. As such feeling unsafe in their environment has been identified as another barrier to physical activity engagement as individuals are reluctant to leave their house[69]. Where you try and promote physical activity can also act as a barrier as individuals with schizophrenia often do not like being in new and unfamiliar environments[70].

Benefits of Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

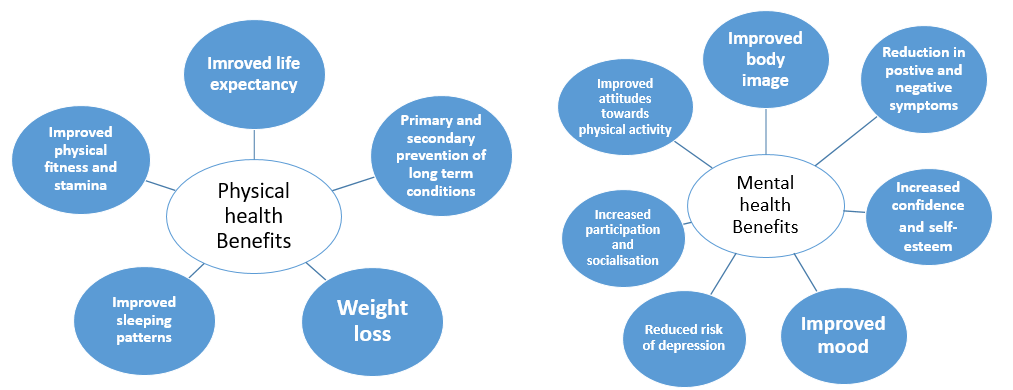

Physical activity is known to have a number of physical and mental health benefits in the general population [58]. It has the potential to improve the quality of life of people with serious mental illness through two routes - by improving physical health and by alleviating psychiatric and social disability[71]. As discussed, physiotherapists have a key role in health promotion and encouraging physical activity is one of the main ways they look to achieve this. This section of the wiki looks to address the physical and mental health benefits of physical activity in people with schizophrenia.

The physical health benefits of physical activity are extensive. A narrative review by Warburton et al.[72] found that regular physical activity is extremely effective in the primary and secondary prevention of a number of chronic conditions e.g. cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, cancer and hypertension. Although the studies did not specifically focus on people with mental illness, if individuals are given the correct advice and support similar results could be seen.

Looking specifically at schizophrenia, improved physical fitness is an important benefit. A systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis which explored the experiences of individuals living with schizophrenia found that having enough fitness to get through an entire day was a great benefit to the individual[69]. The improvements to cardiorespiratory (CR) fitness have been quantitatively reported in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis[73]. The meta-analysis of pre + post test changes in CR fitness found that exercise significantly improved CR fitness (pooled mean predicted increase in VO2 max or VO2 peak was 2.87ml/kg/min p=0.001). Similarly, when compared to control groups, exercise significantly improved CR fitness (p=0.02). Although the overall sample size was small and there were limitations in reporting of important variables e.g. medication, it is clear that physiotherapy interventions should focus on improving physical fitness as it is achievable in this population and is also associated with reduced mortality rates.[72]

Along with improving physical health, physical activity also improves the mental health of people with schizophrenia [74]. One of the main benefits reported is a reduction in positive and negative symptoms. An early systematic review by Faulkner and Biddle [75]found that physical activity can reduce some of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and act as a coping mechanism for positive symptoms. Further research has been carried out and more recent systematic review by Firth et al.[76] found that moderate-vigorous activity significantly improved total symptom score and positive and negative symptom sub-scales. Despite this, the results from this review were limited by the heterogeneity of the interventions and the small sample sizes of included trials and thus a call for further research was made.

A number of qualitative studies have been conducted to establish the benefits from the individuals’ point of view. The systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis referred to earlier in this section found that physical activity was associated with; improved confidence and self-esteem to engage in the community, providing a sense of purpose to the individual and improved attitudes towards physical activity[69]. These findings were also similar to another systematic review by Holley at al.[77] which concluded that physical activity has a benefit on some attributes associated with psychological well-being. A list of these can be seen below. This study was limited by the fact that a range of instruments were used to measure physical activity and there were varying study designs meaning statistical analysis was impossible.

| Physical activity benefits on psychological wellbeing [77] |

|

It is clear to see that physical activity can play an important role in improving both the physical and mental health of individuals with schizophrenia. The evidence surrounding schizophrenia alone is not that extensive and as such many of the studies have major limitations (almost always sample size or study design). In saying that, the evidence that is out there provides a good base to show that physical activity is beneficial in this population although it is clear more research is needed. Knowing about the individual experiences of a person living with schizophrenia and the impact that physical activity has had on their life is very valuable.

Specific Therapy Interventions For People with Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

As mentioned earlier the physiotherapist plays a key role in health promotion and encouraging physical activity in people with schizophrenia. This section of the wiki aims to expand your physiotherapy toolbox by discussing and evaluating common physiotherapy strategies used in mental health including aerobic and strengthening exercise prescription, touch based skills and movement based therapies.

Other techniques to be aware of which are effective in managing anxiety associated with schizophrenia are relaxation, breathing control and tension awareness which are learnt during cardio-respiratory studies in physiotherapy training [51].

Aerobic and Strengthening Exercise[edit | edit source]

It is recommended in the most recent NICE Guidelines[54] that people with psychosis or schizophrenia, especially those taking antipsychotics, should be offered a physical activity/exercise programme by a health care professional. A systematic review on the benefits of exercise in people with schizophrenia[78] found that regular exercise programmes are possible in this population, and that they can have beneficial effects on both physical and mental health. Although, studies included in this review were small and used various measures of physical and mental health it is difficult to establish the true benefits of exercise.

Further to this, a systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken by Pearsall et al.[79] which looked at exercise therapy in adults with serious mental health conditions. There were 8 randomised control trials (RCTs) involved in the review which all explored different exercise programmes including some form of cardiovascular training and resistance training. The effects of these exercise programmes were compared. Exercise programmes in this review were found to have a modest beneficial effect on levels of exercise activity in this population, however no true benefits were found for relief of symptoms.

There were limitations to this review. Firstly the heterogeneity of programmes affected the impact and generalisability of studies found in the review. Secondly, studies failed to quantify the frequency and intensity of exercise in their programmes. And lastly, interventions tended to use non-standardised exercise programmes and a variety of outcome measures. This makes it challenging to recommend the most suitable and effective programme of exercise to individuals with serious mental illness including schizophrenia.

Having said this, there seems to be a lack of continuity between literature results as Rosenbaum et al[80] found through an extensive review of 39 RCTs that physical activity reduced symptoms of schizophrenia and improved aerobic capacity and quality of life among people with mental illness.

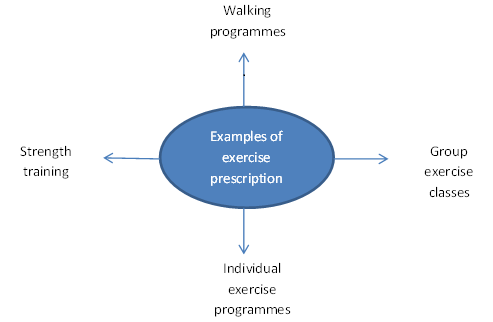

In light of this, here are examples of exercise prescription that could be advised for people with schizophrenia:

Dodd et al.[81] found that group exercise classes which incorporated walking and aerobic elements were deemed feasible in the schizophrenic population with no negative effect and participants in this study experienced weight loss as a benefit.

Group exercises are seen to have their benefits, but we should bear in mind that group situations may not be suitable for everyone and therefore individual tailored treatment plans would be given. Furthermore, Richardson et al.[82] found that individual supervision is hard to do in group situations and treatment cannot be altered as easily to keep in line with individual patient progress. Fogarty et al.[83] carried out a study whereby 6 indivdulas with schizophrenia took part in a 3-month physical conditioning programme aimed at improving cardiovascular fitness, endurance and strength; walking and cycling appeared to be of most benefit and low cost. Two qualified exercise specialists were recruited to design and implement individualised exercise programmes based on the participants fitness levels. They found that the majority of participants improved their physical strength and endurance and exhibited enhanced weight control and flexibility. This alludes to the importance of tailored individual exercise plans as all participants in this study had varying degrees of improvement.

Touch Based Skills[edit | edit source]

We know that skilled touch is a distinctive skill possessed by physiotherapists. This is an essential skill to use when treating patients with mental health conditions such as schizophrenia as their need for physical contact is greatly increased as mental health declines.[84] Treatment such as therapeutic massage can be used as this is proven to reduce levels of anxiety and depression which can be present in this population.[85]

Further evidence has shown that touch based therapies can decrease blood pressure, cortisol levels, stress and gives relief from pain.[86] This is beneficial as people with mental health disorders often feel pain as a result of emotions and therefore physiotherapists can use gentle touch as a way of relieving this pain and increasing patient comfort.[87]

Movement Based Therapies[edit | edit source]

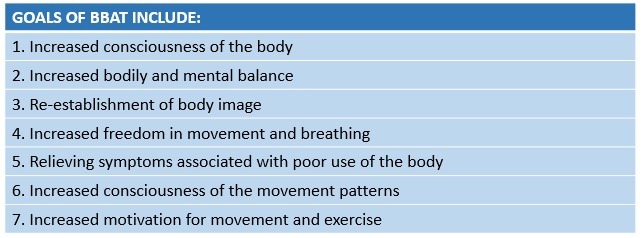

The importance of physical activity and exercise prescription has been presented to you which are forms of movement based therapies. More specific ones used in the rehabilitation of people with schizophrenia are Basic Body Awareness Therapy, The Alexander Technique, Tai Chi and Yoga.[51] These therapies are amongst others and it is advised that you have a look at what these therapies involve as you can use elements of them in practice.

Basic Body Awareness Therapy[edit | edit source]

One of the therapies that is provided by physiotherapists in mental health for people with physical and psychological problems, evident in people with schizophrenia, is basic body awareness therapy (BBAT) which is seen to be growing in popularity.[88] This technique was firstly developed in Scandinavian countries around 40 years ago.[89] In order to practice this technique, physiotherapists must undergo specific training yet basic principles can be used in everyday practice. We have chosen to provide a brief overview of BBAT in order to let you know what treatment methods are currently in place in the mental health setting.

Roxendal[89] suggest that BBAT should be used where disturbances in body awareness are an important part of the pathological picture and hence can be a useful treatment in helping patients with schizophrenia.

The number of therapy sessions needed depends upon the diagnosis and abilities of the patient. One study by Gyllensten et al.[90] found that improvements were seen in people with moderate depression or anxiety in 12 sessions, however, Roxendal[89] found that people with schizophrenia needed approximately 9 months or longer, so therapy can be a lengthy process.

The Impact of BBAT on Patients:

Gyllensten et al.[90] looked at the outcomes of BBAT in patients in psychiatric outpatient care. The treatment group received BBAT along with treatment as usual compared to the control who just received treatment a usual. It was concluded that those who received BBAT had a reduction in their psychiatric symptoms and developed a far more positive attitude towards their body. On top of this, patients appeared more motivated and showed improvements in their physical capacity as well as a more open outlook towards their exercise habits. Follow up/longer term results however were not established in this research study which is a limitation to the results.

The results of the above study were very similar to a qualitative study by Hedlund and Gyllensten[91] which focused on experiences of BBAT in people with schizophrenia. 7 out of the 8 patients reported that they felt they had better contact with their bodies and had become more aware of their movement behaviour, postures and balance. They also reported becoming more physically active and felt they had increased self-esteem and were able to cope more effectively in social situations. A later study by Hedlund and Gyllensten[92] explored physiotherapists views on their experiences of using BBAT. They similarly reported that they notice a positive change in their patients' self esteem after treatment sessions. The physiotherapists in this study also shared experiences of patients reporting that their positive symptoms related to their condition such as hallucinations and hearing voices being were dampened when a state of postural balance was achieved.

The strength of how effective BBAT is also dependendant on how well the patient interacts with the treatment session - so keeping focus and engagement is paramount to patient progress.[93]

Communication Strategies[edit | edit source]

Most physiotherapists will, at some point in their career encounter individuals who suffer from a mental health condition[94]. It may be that the physiotherapist will be treating another condition, but in order to treat the individual holistically, it is important to understand how this condition may impact the delivery of treatment and require a modified approach.

The previously mentioned survey by Dandridge et al.[95] on the views of physiotherapy students towards treating individuals with mental illness, found that one of the key issues was regarding communication. Students raised concerns about how to approach someone with mental illness, discussing a lack of knowledge of how to communicate effectively or adjust their approach to individual needs.

Barriers to Communication[edit | edit source]

Impact of Negative Symptoms[edit | edit source]

In schizophrenia, while the positive symptoms (hallucinations and delusions) are widely recognised as the hallmarks of the condition, it is the negative symptoms which are harder to treat and are more indicative of the long-term ability of the individual to function in society [96]. These negative symptoms include poverty of thought and speech, apathy, anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), lack of motivation and decreased engagement in social interactions [97]. These symptoms have a significant impact on how an individual experiences life. They usually exist prior to the emergence of positive symptoms and will often endure long after the psychotic symptoms have disappeared [98]. Negative symptoms also have implications for physiotherapy treatment as they will affect the client-physiotherapist interactions as well as the ability of the individual to participate actively with their treatment plan.

Deficits in Social Cognition[edit | edit source]

It has also been identified that individuals may experience deficits in social cognition which can impact their ability to interact socially with others. This can include difficulties with; interpreting facial expressions or tone of voice, recognising the emotions or intentions of others and understanding their own feelings and emotions[99]. Furthermore, a study by Lavelle et al. [100] on non-verbal communication found that poor social cognition and increased negative symptoms had an adverse impact on social interactions leading participants to perceive poorer rapport when having conversations with individuals suffering from schizophrenia. Interestingly, a higher level of rapport was reported with individuals exhibiting mild positive symptoms, possibly due to these symptoms manifesting as more engagement with the social interaction. As establishing a therapeutic relationship is essential in patient-therapist interactions [101], it is important that these deficits in social cognition are understood and that clinicians engage in strategies to help establish rapport and ensure effective communication is achieved.

Communication Skills[edit | edit source]

Approaches to Enhance Communication: from Pounds 2010[102][edit | edit source]

A qualitative and descriptive pilot study was carried out to investigate the interaction of an experienced mental health nurse specialist with 3 of her schizophrenic clients. The aim was to describe how she altered her verbal and non-verbal communication in order to enhance effective communication and develop a therapeutic relationship.

Some key approaches that emerged included:

| Exaggeration of facial and vocal cues | As mentioned above, individuals may experience deficits in social cognition, including difficulty reading facial expressions or tone of voice. In this study, the nurse exaggerated her facial expressions (for example, showing concern) or her verbal language (for example, greater inflection in her tone of voice, reflecting a clients’ statement back to them). When applied, these subtle changes in behaviour elicited responses from her clients (such as increased eye contact) and improved their engagement with the interaction. |

| Open body language | Displaying open body language, such as leaning forward, smiling and nodding can demonstrate to the client that the clinician is willing to engage with them and can encourage an individual to be involved in the interaction. |

| Accepting silence/giving time to answer | Some of the negative symptoms (as mentioned above) that an individual with schizophrenia may face are poverty of thought and speech. This means that when asked a question, a person may require longer to gather their thoughts and give an answer. In her interactions with her clients, there were often periods of silence whilst they were considering a question (lasting between 5-15 seconds). |

Promoting Engagement with Treatment[edit | edit source]

Amotivation as a Key Problem[edit | edit source]

Lack of motivation (amotivation) is one of the main negative symptoms experienced by those with schizophrenia [97] and has been identified as having a significant impact on all aspects of behaviour [103]. Motivation is essential for engagement in self-care actions and has an important role in the process of change [104]. A qualitative study by Abed [105] identified lack of motivation to be a major factor that influenced health-related decisions and behaviour. Foussias et al. [106] conducted a longitudinal study and found that amotivation was responsible for 74% of variance in functional outcomes at baseline and 72% of variance at 6-month follow-up, therefore indicating that motivation has a crucial role in predicting the functional outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia. Addressing motivation is of great importance to promote engagement with change and healthy lifestyle choices within this population [104].

Strategies to Enhance Motivation[edit | edit source]

Goal Setting:

The importance of setting patient centered goals within this population will be discussed later on this physiopedia page in more detail. However, it is important to note that working with the individual to set personal meaningful goals can help combat amotivation and influence their willingness to be actively involved in their treatment [107]. Adams and Drake [108] discuss how individuals with serious mental illnesses are capable of meaningfully participating in decisions about their healthcare and it is therefore important to involve them in the planning of treatment. The setting of patient centered goals is one way in which a sense of control can be returned to the patient and can increase their self-determination [107]. Progression towards personal goals is also considered to be a powerful influencing factor in promoting psychological recovery [109].

Social Support:

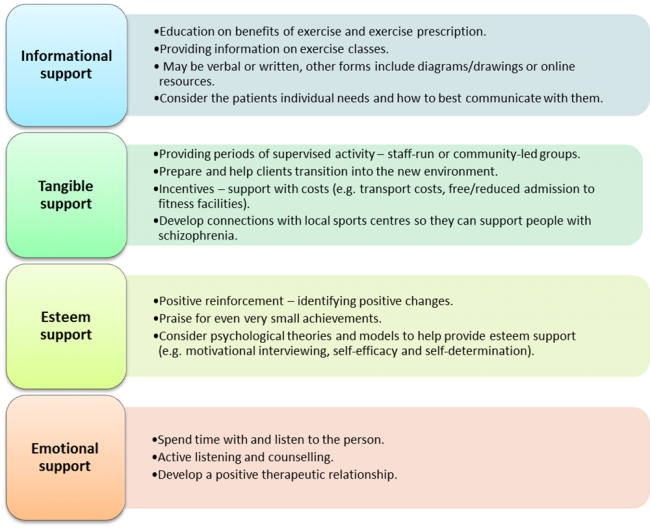

It has been documented that social interactions can have a positive impact on adherence, enjoyment and motivation to change [110], however, individuals with schizophrenia often feel isolated by their condition and have a lack of social support [62]. This is due to a number of factors including paranoia, social skill deficits, social and emotional processing problems, negative symptoms and stigma [107]. A survey of mental health physiotherapists conducted by Soundy et al. [62] investigated the common forms of support they utilised to engage people with schizophrenia in physical activity. Forty physiotherapists provided in depth responses and from this, four dimensions of social support were identified: Informational, tangible, esteem and emotional support. Examples of each dimension are as follows:

While the results from this survey may not be representative or generalisable, a number of key themes were seen to emerge. Many of these suggestions may be useful for physiotherapists to consider in order to better support their clients in their recovery [62].

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a therapeutic technique commonly used in the treatment of mental health conditions and in the UK the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [54] recommends this as a standard treatment to be offered to all individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The aim of CBT is to change how individuals manage and view themselves, particularly in relation to how they experience their condition, and involves metacognition; the ability to think about one’s own thinking [107]. CBT as a specific treatment approach is usually carried out by psychologists or by staff who have undergone specialist training [111], but many of the principles of CBT may be useful within everyday physiotherapy practice.

CBT can be helpful in schizophrenia by challenging beliefs and reasoning in relation to their condition, and through enabling people to establish connections between their thoughts, actions, feelings and symptoms[54]. One example of this is in addressing compliance behavior in those who hear voices (responding to or acting on the commands of the voice). Trower et al.[112] used CBT to challenge beliefs about these hallucinations in a randomized control trial. They reported a decrease in compliance behaviour in addition to reductions in depression and distress scores. Whilst no change was observed in the nature or frequency of the hallucinations, the individuals perceived the voices to have less power over them. CBT used in this way for psychosis has shown strong effect sizes in comparison to no treatment [111], however the evidence shows little benefit when compared to other available therapies [113]. It has been reported in a number of studies that when positive symptoms have been targeted there has also been some improvement in negative symptoms and this has led to recent research into CBT to specifically target negative symptoms [114][98].

Principles of CBT that may be useful in practice

Initially, a trustworthy therapeutic relationship must be built between the client and the therapist and there must be no attempt to label the persons beliefs as irrational [111]. The aim is to help the individual recognise and process maladaptive behaviours and distorted thinking but this should be done collaboratively [115]. It may be helpful for some individuals to adapt a third-person perspective as though discussing someone else’s beliefs, and the therapist can pose questions to facilitate their evaluation of those beliefs [111]. Working with the therapist, behavioural goals are set and a plan is then developed in order to attain them, considering how personal barriers, dysfunctional thoughts and behaviours may be overcome. Systematic discussions are used to help individuals identify and modify their thoughts and behaviours and the use of carefully structured behaviour assignments can assist the person in bringing about these changes in their life[115]. CBT may be more useful to physiotherapists where an individual already has the desire to or is already trying to change [115].

The charity organisation MIND have produced this document about CBT for patients who want to understand more about this therapy. It may be useful for further reading on this topic or to provide information to clients who you feel may benefit from CBT.

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing is another technique that may be of use to help combat lack of motivation in individuals with schizophrenia. It can be described as a way of being with people and helping them to navigate change and must take place in the context of a supportive therapeutic relationship [104]. Motivational interviewing takes the form of a collaborative conversation that is goal-orientated and focused on change, with the purpose of strengthening personal motivation by eliciting and exploring the persons own reasons for change in a supportive environment [115]. It does not externally impose change, but supports change based on their own goals, desires and values [104].

Jackman [116] states that there are five principles:

- Expressing empathy

- Developing discrepancy

- Avoiding conflict and arguments

- Working with rather than fighting resistance

- Supporting self-efficacy.

Five key communication skills are used in motivational interviewing:

- Open-ended questions

- Affirming

- Reflecting

- Summarizing

- Providing information[115].

In this way, the therapist can guide the thoughts of the client by understanding their position and by asking questions to enable them to reach a point where they are intrinsically motivated to change and feel empowered to do so.

There are courses available that teach motivational interviewing and if you think this may benefit your practice you could consider attending one. However, even without formal training the principles of motivational interviewing may be useful to integrate into your everyday client interactions.

Most of the evidence to support the efficacy of motivational interviewing has been in the areas of reducing unwanted behaviours such as alcohol, drug and smoking addictions [115]. With regards to the schizophrenic population, Pickens[104] states that there is moderate evidence to support the use of motivational interviewing for a variety of health-related issues. On reviewing the evidence, most of the literature for this population focuses on medication adherence or co-occurring substance abuse.[117][118]

A Cochrane review[118] on psychosocial interventions for people with severe mental illness (including schizophrenia) to combat substance abuse concluded that the quality of the evidence was low and there was no difference between motivational interviewing and usual care. However, it was stated that motivational interviewing may lead to short-term reductions in substance abuse with multiple sessions.

Vanderwaal[117] conducted a recent review of the literature on the impact of motivational interviewing for medication adherence in those with schizophrenia. This review was able to identify and include just six studies, and of these only one demonstrated a direct relationship between motivational interviewing and improved medication adherence. This article concluded that motivational interviewing may be beneficial for some patients but should not be used as a first line on treatment. The quality of the six studies included was also questionable as there were methodological limitations within each one. Furthermore, five out of the six studies did not look at motivational interviewing as the primary intervention but rather as combined with CBT.

In the promotion of physical activity, there is a lack of evidence on motivational interviewing within the schizophrenic population. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis[119] on those with chronic health conditions included severe mental ill health within their criteria. The results indicated that there was moderate evidence to support a small effect on increasing physical activity. Therefore the use of motivational interviewing within the care plan of an individual with schizophrenia may facilitate physical activity engagement.

In conclusion, there is currently little evidence to support the use of motivational interviewing for those with schizophrenia. It could be argued that there is a need for more research within areas other than substance abuse and medication adherence, such as the encouragement of physical activity.

A Patient Centered Approach: Goal Setting[edit | edit source]

A patient centered approach is vital in the management of people with schizophrenia, particularly with regards to treatment planning and goal setting. The practice of setting goals is common in mental health rehabilitation and in general case-management[109].

Working towards achievable and meaningful goals that have been determined collaboratively can contribute to greater life satisfaction, promote self-management and reduce psychological symptoms. Moreover, attainment of goals improves the emotional and psychological wellbeing of an individual[109].

Clarke et al.[109] states that the levels of distress due to psychotic symptoms are related to goal progress, with greater symptom distress having a negative impact on the progression of goals. It is likely that this is because whilst symptoms are severe the individuals focus will be on alleviating those distressing symptoms rather than looking towards future goals. This issue highlights the importance of a patient-centered holistic approach where the alleviation of symptoms is targeted (e.g. via appropriate medications) whilst also encouraging the attainment of therapeutic goals in order to promote recovery.

Another article by Clarke et al.[120] discusses the types of goals set by individuals with psychiatric disorders (majority of participants suffered from schizophrenia) depending on the stage of recovery that they were in. This study found that those within early stages of recovery focused more on “avoidance” goals (reducing an undesirable outcome such as hearing voices) whilst those is later stages of recovery showed an increase in setting “approach” goals (moving towards a positive outcome).

Also notable, was that physical health goals were overall reported most frequently. These included adhering to mental health medications, weight loss, increased exercise, improved nutrition and physical fitness. This may be due to these types of goals being practical and clearly defined. It is suggested that when life goals become unachievable, simple daily goals may help keep depression at bay and provide a sense of purpose. There is therefore a higher prevalence of health goals at the early stage of recovery and it is likely that these more concrete initial goals must be at least partially met before the individual feels able to progress to goals associated with relationships, employment and personal development.[120]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

A physiotherapist not only requires an understanding of each individual level of physical impairment, they also require an understanding of their mental health issues. Some patients may struggle with directions or remembering exercise sets, whilst others suffer from ill effect of their medications or a combination of both. A physiotherapist must remember all of these factors to aid functional rehabilitation. Furthermore, a physiotherapist can also talk to the individual about their non-adherence to their medications and provide support.

References [edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mental Health Foundation. The Fundamental Facts: The latest facts and figures on mental health. www.mentalhealth.org.uk/content/assets/PDF/publications/fundamental_facts_2007.pdf?view=Standard (accessed 3 January 2016).

- ↑ Mind. Mental Health Facts and Statistics. www.mind.org.uk/information-support (accessed 3 January 2016).

- ↑ Farlex Free Dictionary. Schizophrenia Definition. www.medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/schizophrenia (accessed 5 January 2016).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 World Health Organisation. Mental Health: Schizophrenia. www.who.int/mental_health/management/schizophrenia/en (accessed 5 January 2016).

- ↑ Mind. Schizophrenia. http://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/schizophrenia/causes (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Psychiatric Times. Decreasing Suicide in Schizophrenia. www.psychiatrictimes.com (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ Smith R, De Witt P, Franzsen D. Occupational performance factors perceived to influence the readmission of mental health care users diagnosed with schizophrenia. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 2014;44:51-56. http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/96578104/occupational-performance-factors-perceived-influence-readmission-mental-health-care-users-diagnosed-schizophrenia (accessed 12 December 2015).

- ↑ Royal College of Psychiatrists. Schizophrenia. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/schizophrenia.aspx (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Weinberger DR, Harrison PJ. Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2011

- ↑ NHS Choices. Symptoms of Schizophrenia. www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Schizophrenia/Pages/Symptoms.aspx (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ Living with Schizophrenia. Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia: Understanding Them. http://www.livingwithschizophreniauk.org/advice-sheets/negative-symptoms-understanding (accessed 23 January 2016).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 McNamee L, Mead G, MacGillivray S, Lawrie SM. Schizophrenia, poor physical health and physical activity: evidence-based interventions are required to reduce major health inequalities. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2013;203:239-241. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/203/4/239.long (accessed 2 January 2016).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lindamer LA, Mckibbin C, Norman GJ, Jordan L, Harrison K, Abeyesubge S, Patrick K. Assessment of Physical Activity in Middle-aged and Older Adults with Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 2008;104:294-301.

- ↑ Janney CA, Ganguli R, Richardson CR, Holleman RG, Tang G, Cauley JA, Kriska AM. Sedentary behaviour and psychiatric symptoms in overweight and obese adults with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders (WAIST study). Schizophrenia Research 2013;145:63-68.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Stubbs B, Soundy A, Probst M, De Hert M, De Hert A, Vancampfort D. Understanding the role of physiotherapists in schizophrenia: an international perspective from members of the International Organisation of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Journal of Mental Health 2014;23:125-129.

- ↑ Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Physiology 2012;2:1143-1211.

- ↑ Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Karzmarzyk PT. Impact of Physical Inactivity on the World’s Major Non-Communicable Diseases. Lancet 2012;380:219-229.

- ↑ Gorczynski P, Faulkner G. Exercise Therapy for Schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;(5):CD004412.

- ↑ Phelan M, Stradins L, Morrison S. Physical health of people with severe mental illness. BMJ 2001;322:443-444. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1119672/ (accessed 3 January 2016).

- ↑ Mcreadie RG. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2003;183:534-539. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/183/6/534 (accessed 3 January 2016).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Vancampfort D, Probst M, Helvik Skjaerven L, Catalan-Matamoros D, Lundvik-Gyllensten A, Gomez-Conesa A, Ijntema R, De Hert M. Systematic review of the benefits of physical therapy within a multidisciplinary care approach for people with schizophrenia. Physical Therapy 2012;92:11-23. http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/92/1/11.long (accessed 30 December 2015).

- ↑ Connolly M, Kelly C. Lifestyle and physical health in schizophrenia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2005;11:125-132. http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/11/2/125 (accessed 4 January 2016).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, Casey DE. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. American Heart Journal 2005;150:1115-1121.

- ↑ Cohn T, Prud'homme D, Streiner D, Kameh H, Remington G. Characterizing coronary heart disease risk in chronic schizophrenia: high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2004;49:753-760.

- ↑ Von Hausswolff-Juhlin Y, Bjartveit M, Lindstrom E, Jones P. Schizophrenia and physical health problems. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2009;119(Suppl 438):15-21.

- ↑ Oud MJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Somatic diseases in patients with schizophrenia in general practice: their prevalence and health care. BMC Family Practice 2009;10:1-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2688496/ (accessed 8 January 2016).

- ↑ NICE. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/1-Recommendations (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Lee J, Lyon D. Common Mental Health Conditions in Primary Care. British Journal of Healthcare Management 2009;15:8-11.

- ↑ Nasrallah HA, Harvey PD, Casey D, Csoboth CT, Hudson JI, Julian L, Lentz E, Nuechterlein KH, Perkins DO, Kotowskyd N, Skale TG, Snowden LR, Tandon R, Tek C, Velligan D, Vinogradov S, O’Gormand C. The Management of Schizophrenia in Clinical Practice (MOSAIC) Registry: A focus on patients, caregivers, illness severity, functional status, disease burden and healthcare utilization. Schizophrenia Research 2015;166:69-79. http://www.schres-journal.com/article/S0920-9964(15)00226-1/abstract (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- ↑ The London School of Economics and Political Science. Promotion, prevention and early intervention dramatically cut the costs of mental ill health, says government – sponsored research report. http://www.lse.ac.uk/newsAndMedia/news/archives/2011/04/Department_of_Health.aspx (accessed 20 January 2016).

- ↑ Guo JY, Huhtaniska S, Miettunen J, Jääskeläinen E, Kiviniemi V, Nikkinen J, Moilanen J, Haapea M, Mäki P, Jones PB, Veijola J, Isohanni M, Murray GK. Longitudinal regional brain volume loss in schizophrenia: Relationship to antipsychotic medication and change in social function. Schizophrenia Research 2015;168:297-304. http://www.schres-journal.com/article/S0920-9964(15)00331-X/fulltext (accessed 5 January 2016).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Zhang J, Rosenheck R, Mohamed S, Zhou Y, Chang Q, Ning Y, He H. Association of symptom severity, insight and increased pharmacologic side effects in acutely hospitalized patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2014;55:1914-1919 http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/ (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ Pringle R. Psychosis and Schizophrenia: a Mental Health Nurse’s Perspective. Nurse Prescribing 2013;11:505-508.

- ↑ NICE. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/1-Recommendations (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Ashoorian D, Davidson R, Rock D, Gudka S, Clifford R. A review of Self Report Medication Side Effect Questionnaires for Mental Health Patients. Psychiatry Research 2014;219:664-673. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178114004867 (accessed 5 Oct 2015).

- ↑ El-Missiry A, Elbatrawy A, El Missiry M, Moneim DA, Ali R, Essawy H. Comparing cognitive functions in medication adherent and non-adherent patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2015;70:106-112.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 SIGN. SIGN 131. Management of Schizophrenia. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign131.pdf (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ Offord S, Lin J, Wong B, Mirski D, Baker RA. Impact of Oral Antipsychotic Medication Adherence on Healthcare Resource Utilization Among Schizophrenia Patients with Medicare Coverage. Community Mental Health Journal 2013;49:625-629.

- ↑ Schirmer UB, Steinert T, Flammer E, Borbé R. Skills-based medication training program for patients with schizophrenic disorders: A rater-blind randomized controlled trial. Patient Preference and Adherence 2015;9:541-549. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4386772/ (accessed 5 January 2016).

- ↑ Kalin M, Kaplan S, Gould F, Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Harvey PD. Social cognition, social competence, negative symptoms and social outcomes: Inter-relationships in people with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2015;68:254-260.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Michalopoulou PG, Lewis SW, Wykes T, Jaeger J, Kapura S. Treating impaired cognition in schizophrenia: The case for combining cognitive-enhancing drugs with cognitive remediation. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;23:790-798. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X13001156 (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- ↑ Lee J, Green MF, Calkins ME, Greenwood TA, Gur RE, Gur RC, Lazzeroni LC, Light GA, Nuechterlein KH, Radant AD, Seidman LJ, Siever LJ, Silverman JM, Sprock J, Stone WS, Sugar CA, Swerdlow NR, Tsuang DW, Tsuang MT, Turetsky BI, Braff D. Verbal working memory in schizophrenia from the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia (COGS) Study: The moderating role of smoking status and antipsychotic medications. Schizophrenia Research 2015;163:24-31.

- ↑ Lahti J, Lallukka T, Lahelma E, Rahkonen O. Leisure-time Physical Activity and Psychotropic Medication: A Prospective Cohort Study. Preventative Medicine 2013;57:173-177. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743513001825 (accessed 5 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Richardson CR, Faulkner G, McDevitt J, Skrinar GS, Hutchinson DS, Piette JD. Integrating Physical Activity Into Mental Health Services for Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 2005;56:324-331. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.324 (accessed 5 Oct 2015).

- ↑ Everett T, Dennis M, Ricketts E. Physiotherapy in Mental Health. Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995.

- ↑ Oliveira VC, Ferreira ML, Pinto RZ, Filho RF, Refshauge K, Ferreira PH. Literature Review: Effectiveness of Training Clinicians' Communication Skills on Patients' Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2015;38:601-616.

- ↑ Walkeden SA, Walker KM. Perceptions of physiotherapists about their role in health promotion at an acute hospital: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy 2015;101:226-231.

- ↑ Ashoorian D, Davidson R, Rock D, Gudka S, Clifford R. A review of Self Report Medication Side Effect Questionnaires for Mental Health Patients. Psychiatry Research 2014;219:664-673. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178114004867 (accessed 5 Oct 2015).

- ↑ NHS. Physiotherapy. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Physiotherapy/pages/introduction.aspx (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Commissioning Mental Health Services. London:The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 2008.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Moving in Mind: The role of Physiotherapy in mental health and wellbeing in Scotland. Edinburgh:CSP Scotland, 2010

- ↑ Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:334-241.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Kaur J, Masaun, M, Bhatia, MS. Role of Physiotherapy in Mental Health Disorders. Delhi Psychiatry Journal 2013;16:404-408.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/chapter/recommendations (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Health promotion. http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (accessed 3 January 2016).

- ↑ Everyday Health. Exercise and Physical Activity: What's the Difference?. http://www.everydayhealth.com/fitness/basics/difference-between-exercise-and-physical-activity.aspx (accessed 2 January 2016).

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/physical-activity-recommendations-18-64years.pdf (accessed 10 January 2016).

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006;174:801-809.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Mind. Physical activity, sport and mental health. http://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-for-everyday-living/physical-activity-sport-and-exercise/#.Vpoc-hWLTIU (accessed 8 January 2016).

- ↑ Johnstone R, Nicol K, Donaghy M, Lawrie S. Barriers to uptake of physical activity in community-based patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health 2009;18:523-532.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Rastad C, Martin C, Asenlof P. Barriers, benefits and strategies for physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Physical therapy 2014;94:1467-1479. http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/94/10/1467.long (accessed 8 January 2016).

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 Soundy A, Stubbs B, Probst M, Hemmings L, Vancampfort D. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity among persons with schizophrenia: a survey of physical therapists. Psychiatry Services 2014;65:693-696. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.201300276 (accessed 11 January 2016).

- ↑ Ask. What are some examples of psychological barriers? http://www.ask.com/world-view/examples-psychological-barriers-d2ed60d6837cf59 (accessed 18 January 2016).

- ↑ Mental Health Foundation. Employment is vital for maintaining good mental health. http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-news/blog/120629/ (accessed 14 January 2016).

- ↑ Government Equalities Office. Access to work. https://www.gov.uk/access-to-work/overview (accessed January 2016).

- ↑ Government Equalities Office. Law and justice system guidance. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance (accessed December 2015).

- ↑ United Kingdom Government. Mental Health Act 1983. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1983/20/pdfs/ukpga_19830020_en.pdf. (accessed 15 January 2016)

- ↑ Lögdberg B, Nilsson LL, Levander MT, Levander S. Schizophrenia, neighbourhood, and crime. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2004;110:92-7.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Soundy A, Freeman P, Stubbs B, Probst M, Coffee P, Vancampfort D. The transcending benefits of physical activity for individuals with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Psychiatry Research 2014;220:11-19.

- ↑ Leutwyler H, Hubbard E, Slater M, Jeste D. “It’s good for me”: Physical Activity in Older Adults with Schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal 2014;50:75-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3812241/ (accessed 2 January 2015).

- ↑ Richardson CR, Faulkner G, Mcdevitt J, Skrinar GS, Hutchinson DS, Piette JD. Integrating Physical Activity Into Mental Health Services for Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 2005;56:324-331.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006;174:801-809.

- ↑ Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Exercise improves cardiorespiratory fitness in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research 2015;169:453-457.

- ↑ Scheewe TW, Backx F, Takken T, Jorg F, Van Srater AC, Kroes AG, Kahn RS, Cahn W. Exercise therapy improves mental and physical health in schizophrenia: a randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2013;127:464-473.

- ↑ Faulkner G, Biddle S. Exercise as an adjunct treatment for schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health 1999;8:441-457.

- ↑ Firth J, Cotter C, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR. A systematic review and meta-Analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychological Medicine 2015;45:1343-1361.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Holley J, Crone D, Tyson P, Lovell G. The effects of physical activity on psychological well-being for those with schizophrenia: A systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2011;50:84-105.

- ↑ Bernard P, Ninot G. Benefits of exercise for people with schizophrenia: a systematic review. Encephale 2012;38:280-287. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22980468 (accessed 23 January 2016).

- ↑ Pearsall C, Smith DJ, Pelosi A, Geddes J. Exercise therapy in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:117-128. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4018503 (accessed 23 January 2016).

- ↑ Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB. Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical psychiatry 2014;75:964-974. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813261 (accessed 23 January 2016).

- ↑ Dodd KJ, Duffy S, Stewart JA, Impey J, Taylor N. A small group aerobic exercise programme that reduces body weight is feasible in adults with severe chronic schizophrenia: a pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation 2011;33:1222-1229.

- ↑ Richardson CR, Faulkner G, McDevitt J, Skrinar GS, Hutchinson DS, Piette, JD. Integrating Physical Activity Into Mental Health Services for Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 2005;56:324-331. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.324 (accessed 15 January 2016).

- ↑ Fogarty M, Happell B, Pinikahana J. The Benefits of an Exercise Program for People with Schizophrenia: A Pilot Study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2004;28:173-176. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15605754 (accessed 14 January 2016).

- ↑ Salzmann-Erikson M, Eriksson H. Encountering touch: a path to infinity in psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2005;26:843-52.

- ↑ Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta analysis of massage therapy research. Psychological Bulletin 2004;130:3-18.

- ↑ Preyde M. Effectiveness of massage therapy for sub acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2000;162:1815-20.

- ↑ Harvard Health Publications. Depression and Pain. www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/depression_and_pain (accessed 13 January 2016).

- ↑ The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Smart Moves. http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/smart-moves (accessed 16 January 2016).

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Roxendal G. Body Awareness Therapy and the Body Awareness Scale: Treatment and evaluation in psychiatric physiotherapy. Sweden, 1985

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Gyllensten AL, Hansson L, Ekdahl C. Outcome of Basic Body Awareness Therapy. A Randomized Controlled Study of Patients in Psychiatric Outpatient Care. Advances in Physiotherapy 2003;5:179-90. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14038109310012061?journalCode=iejp19 (accessed 14 January 2016).

- ↑ Hedlund L, Gyllensten AL. The experiences of basic body awareness therapy in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2010;14:245-254. http://resolver.ebscohost.com (accessed 14 January 2016).

- ↑ Hedlund L, Gyllensten AL. The physiotherapists' experience of Basic Body Awareness Therapy in patients with schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2013;17:169-176. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S136085921200229X (accessed 19 January 2016).

- ↑ Skjaerven LH, Kristoffersen K, Gard K. An eye for movement quality: A phenomenological study of movement quality reflecting a group of physiotherapists' understanding of the phenomenon. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2008;24:13-27.

- ↑ Priestley S. Helping when a mind hurts. Frontline 2011;17. www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/helping-when-mind-hurts (accessed 6 January 2016).

- ↑ Dandridge T, Stubbs B, Carolyn R, Soundy A. A survey of physiotherapy students’ experiences and attitudes towards treating individuals with mental illness. International Journal or Therapy and Rehabilitation 2014;27:324-330. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrew_Soundy/publication/263478359 (accessed 27 December 2015).

- ↑ Lang FU, Kosters M, Lang S, Becker T, Jager M. Psychopathological long-term outcome of schizophrenia – a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2013;127:173-82.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Weinberger DR, Harrison PJ. Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Staring ABP, Huurne M-AB, van der Gaag M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for negative symptoms (CBT-n) in psychotic disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 2013;44:300-6.

- ↑ Koelkebeck K, Wilhelm C, Cross-cultural aspects of social cognitive abilities in schizophrenia. In: Lysaker PH, Dimaggio G, Brune M, editors. Social Cognition and Metacognition in Schizophrenia. London: Academic Press, 2014. p29-47.

- ↑ Lavelle M, Healey PGT, McCabe R. Is Nonverbal Communication Disrupted in Interactions Involving Patients With Schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Bulletin 2012;39:1150-8.

- ↑ Hewitt J, Coffey M. Therapeutic working relationships with people with schizophrenia: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005;52:561-70.

- ↑ Pounds KG. Client-Nurse Interaction with Individuals with Schizophrenia: A Descriptive Pilot Study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2010;31:770-3.

- ↑ Choi J, Medalia A. Intrinsic Motivation and Learning in a Schizophrenia Spectrum Sample. Schizophrenia Research 2010;118:12-19.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 104.4 Pickens J. Development of Self-Care Agency through Enhancement of Motivation in People with Schizophrenia. Self-Care, Dependent-Care and Nursing 2012;19:47-52.

- ↑ Abed H. What factors affect the lifestyle choices of people with schizophrenia? Mental Health Review Journal 2010;15:21-27.

- ↑ Foussias G, Mann S, Zakzanis KK, Vanreekum R, Agid O, Remington G. Prediction of longitudinal functional outcomes in schizophrenia: The impact of baseline motivational deficits. Schizophrenia Research 2011;132:24-27.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 Dopke CA, Batscha CL. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals With Schizophrenia: A Recovery Approach. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 2014;17:44-71.

- ↑ Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared Decision-Making and Evidence-Based Practice. Community Mental Health Journal 2006;42:85-105.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 109.3 Clarke SP, Oades LG, Crowe TP, Caputt P, Deane F. The role of symptom distress and goal attainment in promoting aspects of psychological recovery for consumers with enduring mental illness. Journal of Mental Health 2009;18:389-97.

- ↑ Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Vansteenkiste M, De Herdt A, Scheewe TW, Soundy A, Stubbs B, Probst M. The importance of self-determined motivation towards physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 2013;210:812-8.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 O’Connor K, Lecomte T. An overview of cognitive behaviour therapy in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In: Ritsner MS, editor. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume III: Therapeutic Approaches, Comorbidity, and Outcomes. Dordrecht:Springer Netherlands, 2011. p245-65.

- ↑ Trower P, Birchwood M, Meaden A, Byrne S, Nelson A, Ross K. Cognitive therapy for command hallucinations: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2004;184:312-20.

- ↑ Jones C, Hacker D, Cormac I, Meaden A, Irving CB. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(4):CD008712

- ↑ Klingberg S, Wolwer W, Engel C, Wittore A, Herrlich J, Meisner C, Buchkremer G, Wiedemann G. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia as primary target of cognitive behavioral therapy: Results of the randomized clinical TONES study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2011;37:98-110.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 115.4 115.5 McGrane N, Cusack T, O’Donoghue G, Stokes E. Motivational strategies for physiotherapists. Physical Therapy Reviews 2014;19:136-142.

- ↑ Jackman K. Motivational interviewing with adolescents: an advanced practice nursing intervention for psychiatric settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Nursing 2012;25:4-8.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Vanderwaal FM. Impact of Motivational Interviewing on Medication Adherence in Schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2015;36:900–904.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Hunt GE, Siegfried N, Morley K, Sitharthan T, Cleary M. Psychosocial interventions for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse (Cochrane review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(10): CD001088

- ↑ O’Halloran PD, Blackstock F, Shields N, Holland A, Iles R, Kingsley M, Bernhardt J, Lannin N, Morris ME, Taylor NF. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in people with chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation 2014;28:1159-1171.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Clarke S, Oades LG, Crowe TP. Recovery in mental health: A movement towards well-being and meaning in contrast to avoidance of symptoms. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2012;35:297-304.