Physical Activity Guidelines for Traumatic Brain Injury

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Physical activity, defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, benefits every aspect of health and in daily life can be categorized into occupational, sports, conditioning, household, or other activities, including exercise, which is planned, structured, and repetitive and has as a final or an intermediate objective the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness. [1] Regular physical activity shows benefits for everyone including children, adolescents, adults, older adults, and people with a disability across all ethnic groups and most importantly has been shown to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases, such as Coronary Heart Disease, Type 2 Diabetes, Stroke, Cancer, Osteoporosis and Depression. [2] Physical activity can also improve bone and functional health and as a key determinant of energy expenditure, is fundamental to energy balance and weight control.

Physical inactivity has been identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally or 6% of deaths. [3] Globally 23 percent of adults 18+ and 80 percent of adolescents are insufficiently active, and this number is higher among individuals with a disability. Current evidence suggests that inactivity has negative effects on everyone, but the effects appear to be worse for people with disability, particularly for those with a traumatic brain injury. [4]

Physical Activity and Traumatic Brain Injury[edit | edit source]

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

A wide range of barriers exist that limit and in some cases prevent individuals with a traumatic brian injury from being active, which increases the risk of developing further secondary and chronic health conditions. Barriers to participation in physical activity vary depending on age, severity of traumatic brain injury, type of impairment and length of time since initial injury. [5]

Personal[edit | edit source]

- Feel Self-Conscious

- Lack of Time

- Lack of Interest

- Lack of Energy

- Lack of Knowledge regarding Benefits of Physical Activity

- Lack of Knowledge of Where to Exercise

- Lack of Knowledge of Types of Physical Activity

- Lack of Counselling by a Physician

Condition Related[edit | edit source]

Physical Impairment

- Decreased Mobility

- Decreased Balance

- Decreased Muscle Strength

- Changes to Oxidative Metabolism

- Increased Fatigue

- Pain limits physical activity

Cognitive & Psychosocial

- Diminished drive / motivation to participate in physical activity

Environmental[edit | edit source]

- Barriers in Outdoor Areas i.e. uneven pathways [8]

- Lack of Accessible Facilities e.g. limited adaptive equipment or space between equipment, no ramps or elevators, poor signage

- Lack of Transportation

- Cost of the Program

- Poor Trainer / Coach Knowledge or Awareness of Traumatic Brain injury and feel they are unable to hel

Societal[edit | edit source]

- Lack of Support

- Poor Community Integration

Benefits Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

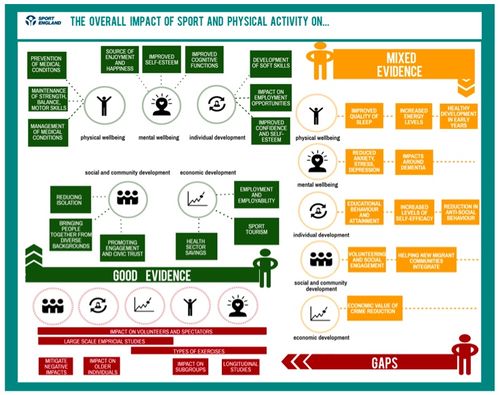

There is strong evidence demonstrating that being physically active is beneficial to individuals in terms of their physical and mental health, well-being, cognitive function, and increased longevity with positive outcomes for the community and wider society through health savings, social engagement, and greater productivity. [2][9] Physical activity not only promotes good health and functioning and helps prevent and manage disease; it also contributes to a range of wider social benefits for individuals and communities. The relevance and importance of the wider benefits of physical activity for individuals vary according to life stage and various other factors but include: improved learning and attainment; managing stress; self-efficacy; improved sleep; the development of social skills; and better social interaction.

According to the Expert Committee that developed the US Guidelines on Physical Activity in 2008, “the health benefits of being habitually physically active appear to apply to all people regardless of age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and...people with physical or cognitive disabilities.”

Health[edit | edit source]

- Improved Cognitive Function including improved processing speed, executive functioning, learning ability and overall cognitive function [11][12]

- Higher Perceptions of Global Health, Health Status and Quality of Life [13][14]

- Decreased Incidence of Depression [13][14]

- Improved Sleep [15]

Psycho-Social[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation developed Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health with the overall aim of providing national and regional level policy makers with guidance on the dose-response relationship between the frequency, duration, intensity, type and total amount of physical activity needed for the prevention of Non Communicable Diseases. While these guidelines were not specifically tailored to the traumatic brain injury population, the World Health Organization suggest that the recommendations could be applied to adults with a disability with adjustment to the guidelines for each individual based on their exercise capacity and specific health risks or limitations. [4][17]

American College of Sports Medicine Physical Activity Guidelines for Traumatic Brain Injury[edit | edit source]

Exercise guidelines for individuals with a traumatic brain injury have been published by the American College of Sports Medicine, which recommend exercising at a frequency of three to five times per week, at an intensity of 40% to 70% of peak oxygen uptake, or a 13/20 Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), and for a duration of 20 to 60 minutes using an appropriate mode of exercise e.g. walking, swimming, cycling, that will depend upon the individual's physical ability.Conclusion[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health reports. 1985 Mar;100(2):126.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- ↑ Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The lancet. 2012 Jul 27;380(9838):219-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 World Health Organisation. Physical Activity. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/ [accessed 20 May 2016]

- ↑ Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. 2014. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine </nowiki>&Science in Sports, 24 (6), 871-881

- ↑ National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD). (2019). Addressing Barriers. Available at: https://www.nchpad.org/1246/5928/A~Proactive~Approach~to~Inclusive~Fitness [Accessed 17 September 2019].

- ↑ Empower. Disability and Health Inequalities - Introduction to the Breaking Barriers series. Available from: https://youtu.be/5lfUiH77BxA[last accessed 30/09/19]

- ↑ Hassett L, Moseley AM, Harmer AR. Fitness training for cardiorespiratory conditioning after traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(12).

- ↑ Institute,UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines, 7 September 2019, Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf, [Accessed 27th September 2019]

- ↑ Brainline. How Exercise Can Heal the Brain after a Traumatic Brain Injury. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUevLwJGMlQ[last accessed 30/09/19]

- ↑ Chin LM, Keyser RE, Dsurney J, Chan L. Improved cognitive performance following aerobic exercise training in people with traumatic brain injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2015 Apr 1;96(4):754-9.

- ↑ Grealy, M.A., Johnson, D.A., and Rushton, S.K. Improving cognitive function after brain injury: the use of exercise and virtual reality. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999; 80: 661–667

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gordon, W.A., Sliwinski, M., Echo, J., McLoughlin, M., Sheerer, M.S., and Meili, T.E. The benefits of exercise in individuals with traumatic brain injury: a retrospective study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998; 13: 58–67

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Wise EK, Hoffman JM, Powell JM, Bombardier CH, Bell KR. Benefits of exercise maintenance after traumatic brain injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2012 Aug 1;93(8):1319-23.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Hoffman, J.M., Bell, K.R., Powell, J.M. et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve mood after traumatic brain injury. PM R. 2010; 2: 911–919

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Thornton, M., Marshall, S., McComas, J., Finestone, H., McCormick, A., and Sveistrup, H. Benefits of activity and virtual reality based balance exercise programmes for adults with traumatic brain injury: perceptions of participants and their caregivers. Brain Inj. 2005; 19: 989–1000

- ↑ World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. World Health Organization; 2010.

![Common Barriers Experienced by People with a Disabilities [6]](/images/thumb/2/2d/1918.JPG/500px-1918.JPG)