Physical Activity, Sport and Recreation for Young People with Physical Disabilities

Introduction[edit | edit source]

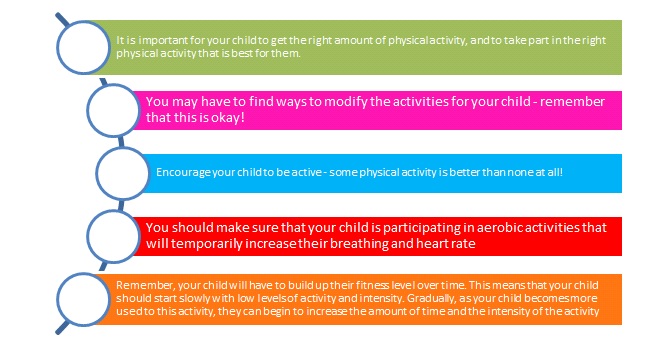

Children should aim to take part in at least one hour of medium to hard intensity physical activity every day.[1] Encouraging children to be active with the distractions of technology can often be difficult but even more so if the child has a disability or medical condition. Guidance on how activities and exercises can be adapted can often be challenging that individuals living with disabilities were 82% more likely to take part in regular physical activity if a health professional advised it?[2]

Benefits of Physical Activity![edit | edit source]

Physical activity is crucial for a child’s health an wellbeing, here are a few other benefits:

- Can help a child feel more confident about themselves!

- Can help to maintain a child's weight

- Can improve motor skills, so they may find it a bit easier to perform certain movements they may have struggled with before[3]

- Can improve their participation in school and P.E. classes[3]

- Can improve their mood[3]

- Can help improve their breathing

- Can improve their bone, muscle and heart health

- Can reduce the risk of falls and fractures

- Active wheelchair users are less likely to have pressure sores and kidney complications than those who don’t take part in much physical activity.

- Physical activity can also help a child with problems related to their behaviour[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- Physical activity plays an important part in maintaining good fitness and it lowers their chances of getting a lifelong illnesses and/or other health conditions.[11]

Benefits and Disadvantages o Physical Activity for Wheelchair Users[edit | edit source]

Manual wheelchair users often feel pain around their shoulders because shoulders are naturally made for moving around rather than for constantly lifting and pushing lots of weight![12] The day-to-day life of a person who uses a manual wheelchair often involves a lot of pushing and lifting; from pushing themselves around all day to lifting themselves into and out of their wheelchair. This means that any shoulder injury may limit the amount of things they can normally do for themselves.[12][13]

Many injuries can happen from carrying out a shoulder movement for a specific task that is difficult to complete. For example, lifting a very heavy object over the head or by repeatedly performing a normal movement so often that your joint begins to wear down.[12] Activities like pushing a wheelchair for long distances or transferring in and out of a wheelchair many times throughout the day can cause an overuse injury.[12][13]

Getting exercise through sports is a great way to help strengthen your child’s muscles. Making sure their muscles and joints are strong means they will have the best chance at living independently, and goes a long way to improving their overall wellbeing![12][13]

It is important to minimise the risk of injury. Some common problems that can occur and how to avoid them include:

- Skin

- Prevent blisters on hands with gloves

- Prevent wheel-burns by covering the area with protective material

- Decrease bruising by placing pads where needed, i.e. bony areas and retaining straps

- Cover blisters

- Swimming

- Protect skin

- Place mats at the poolside during transfers

- Protect the feet

- Muscles and Joints

- Monitor for overuse

- Closely observe any muscle or joint pain

- Maintain flexibility with stretching

- Hyperthermia (High body temperature)

- Take into account temperature if exercising outdoors

- Encourage to drink lots of water

- Avoid direct sunlight

- Pressure Sores

- Use cushions and padding where needed

- Change position and shift weight regularly

Risks of Inactivity[edit | edit source]

Not taking part in enough physical activity is one of the biggest risk factors for death around the world. Individuals with disabilities have a 3 times higher chance of having health-related problems than individuals who do not have disabilities.[14] People who are less active have a 20-30% higher risk of death compared to people who are more active. Physical inactivity can also lead to fatigue and depression, putting on more weight, becoming more dependent on others. It also increases the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke, pressure sores, weaker bones, depression and several cancers.[14]

Barriers and Facilitators to Exercise[edit | edit source]

A child’s disability may make taking part in physical activity more difficult as it may limit range of movement at joints, flexibility, agility, strength or endurance, and balance and coordination.[15] Any of these limitations, may demotivate a child from taking part in more activities as well as:

- Pain and/or fatigue may also limit a child from being active. It can often be due to overtraining, sitting for long periods or wearing their assistive devices such as an orthosis.[15]

- A child may take more time to go outdoors during school breaks if they have to handle and wear orthoses. They may see it as an inconvenience and may stop using this time to play outside with their friends.[16]

- Physical strength and skills that a child develops may be lost due to interruptions in training or recovery after surgery.[15]

- As a child gets older, the gap between able-bodied children and disabled athletes in terms of physical strength and agility grows larger. With this, the skills gap also widens and sports become more competitive. As a result, it may become more difficult for a child to continue taking part in mainstream activities.[15]

Psychosocial and Emotional Barriers[edit | edit source]

- Embarrassment, vulnerability, disappointment and shame at appearing physically incapable are just some of the uncomfortable emotions a child may experience. These feelings may lower their confidence and self-esteem. They may also feel frustrated at taking longer to learn a new skill and as a result, may avoid taking part in certain activities altogether.[15]

- Negative attitudes from parents, staff and peers can hinder a child’s interest in physical activity.[17] It may come in the form of teasing from other children and/or teachers who lack training in adapting activities to suit your child needs. This also results in excluding them from taking part in school clubs and activities.[18]

- As a result, a child may feel singled out and alone. These feelings can sometimes lead them to believe they are not good enough and can make it more difficult for them to persevere with physical activity.[16]

Cost and Environmental Barriers[edit | edit source]

- Finding time in the midst of appointments with various therapists, school runs, caring for other children, along with day-to-day duties poses as one of the main barriers to including physical activity in a child’s life. With the extra expenses of caring for a child with a disability and fewer earnings due to taking on caring responsibilities instead of work, there is often little money leftover to spend on membership for various classes and clubs.[18]

- Sporting opportunities specific to a child’s abilities, as well as those available locally are often poorly advertised.[19][18]

- Sporting facilities that cater for a child’s needs may be often lacking in certain areas such as shortage of qualified staff willing to supervise activities for children with motor impairments and lack of equipment to aid sports, especially as a child gets older.[20][16]

- Unfortunately, local clubs and societies may also face difficulties such recruiting enough children to make up teams or finding other teams to play against.[15]

- With this comes the barrier of transport. Living far away from such facilities and having to travel to introduce a child to such activities, may not be always be easy to access via public transport.[15]

- One off programmes as well as long waiting lists for specialised classes may also pose as a barrier to a child’s participation in physical activity.[18]

- Specialised adaptive equipment for sports is also costly and not always readily available.[21]

- Environmental barriers may also get in the way to accessing sporting facilities. These may include lack of curb cuts and ramps, doors being too narrow for wheelchair access and reception desks being too high to talk to staff.

Social Facilitators[edit | edit source]

- Studies haven shown that children (aged 4-7) of physically active mothers are twice as likely to take part in physical activity than children with inactive mothers. The are also 3.5 times more likely to engage in physical activity if they have active fathers. Those with two active parents are almost 6 times more likely to be physically active than children of inactive parents.[22]

- Encouraging parents to take an active interest in their child’s daily schedule. Suggest reducing screen time during the day and encouraging children to go outside and play. Factor in the time taken to go to the park or a class to include physical as a daily requirement.

- Habits of friends and siblings can also impact a child’s decision to take part in activities. Children enjoy belonging to something or someone; taking part in activities with family and friends can give them a feeling of togetherness and of being noticed and accepted as part of a group.[23] It also gives them the opportunity to meet others with similar abilities and most importantly to be seen as more than their disability!

How to book: Call 0131 447 5700

Prices: For the day, family (up to 4) is £22, child (up to 16 years) is £4, parent and child is £10, full membership is £275.

If you are keen to get your child involved in golf, there are locally based PGA professionals who offer lessons. Prices range upward of £20 per half hour. Scottish Disability Golf, which supports golf for the disabled person in Scotland, have also used professionals at Melville, Duddingston, Dalmahoy and Houston in recent months.

Race Running & Athletics[edit | edit source]

Has your child ever wanted to zoom around the track like the superhero Flash? Race running might just be the sport for them. A recognized international disability sport, race running involves running around the track with the support of a specialised bike. Race Running is a fantastic way for your child to improve their overall fitness, strength and well-being.

Although there are currently no active Race Running clubs within the Lothian area, there may opportunities in the near future. In the meantime, your child can get fitted for a running bike at all-ability cycling hub based in Bangholm Outdoor Education Centre and whiz across flat walking paths.

For further information on getting fitted for and renting running bikes, contact David Glover at the All Abilities Bike Club by telephone (07500 069357) or email ([email protected]).

Check out the following video to get a better idea of what it's all about:

If you live in Forth Valley, the Forth Valley Flyers Club is an athletics club for individuals (aged 10 and over) with a physical, sensory or learning disabilities from Falkirk, Stirling and Clackmannanshire. They provide sessions for children, young people and adults involving everything from walking / running 40m to 1500m, javelin and shot putt to bean bag throw, long jump and standing long jump. The also have a Race Running Squad for athletes with restricted mobility. The bikes are provided and can be used by individuals (aged 3-4 and over). The sessions are held at Grangemouth Athletics Stadium on the following days:

Fridays: 5:30pm - 6:45pm (Athletics)

Tuesdays: 5:30pm - 6:45pm (Race Running)

Prices: £2 per week, £10 membership per year

For further information contact Ann Finlayson by email ([email protected]).

Indoor Activities[edit | edit source]

Play[edit | edit source]

If you thought things could not get any more fun, they just have! The Yard is a purpose built indoor and outdoor adventure playground for children and young people living with disabilities. It lies in the heart of Edinburgh and, quite simply could not cater for people with additional support needs any better than it already does. This is a place for your whole family; it will give you and your children the chance to explore your surroundings and interact with others. Most importantly, your child will make new friends who won’t look at them differently and who experience the same struggles they do.

Check out what parents have to say about The Yard:

Ages: 3-25

Prices: £5-7 per month, for visiting members £15 (5 visits) and £25 (10 visits) per year.

How to find it: The Yard has a site here in Edinburgh (22 Eyre Place Lane, Edinburgh, EH3 5EH)

For more information, visit their website or call 0131 476 4506.

Dance[edit | edit source]

Did you know that you can get a great workout from dancing? If your child enjoys watching 'Strictly Come Dancing’ and moving along to music, why not head over to Dance Base?

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is hugely important for everyone, and children with physical disabilities are no exception. Unfortunately, children with disabilities are less active than their able-bodied peers and therefore encouraging their participation in sporting and recreational activities is vital.[20] In this online resource we have talked you through the various physical and psychological advantages of being physically active such as, but not limited to improvements in body function, heart and bone health, psychological wellbeing and social engagement.[20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Physical Activity. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/. [Accessed 16th November 2016].

- ↑ Physical Activity and Health. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Emck C, Bosscher R, Beek P, Doreleijers T. Gross motor performance and self‐perceived motor competence in children with emotional, behavioural, and pervasive developmental disorders: a review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2009, Jul 1;51(7):501-17.

- ↑ Moone MS, Renzaglia A. Physical fitness and the mentally retarded: a critical review of the literature Journal of Special Education. 1982;16(16) 3: 269 -287.

- ↑ Nishiyama S, Kuwahara T, Maatsudea I. Decreased bone density in severely handicapped children and adults with reference to the influence of limited mobility and anticonvulsant medication European Journal of Pediatrics. 1986; 144(5): 457-763.

- ↑ Lancioni GE. Procedures for promoting independent activity in people with severe and profound learning disability: A brief review: Mental Handicap Research. 1994; 7 (3):237-256

- ↑ Lancioni GE, O'Reilly MF. A review of research on physical exercise with people with severe and profound developmental disabilities. Research in Development Disabilities. 1998; 19(6): 477-492.

- ↑ Washburn RA, Zhu W, McAuley E, Frogle M, Figonis SF. The physical Activity Scale for individuals with physical disabilities: Development and Evaluation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002; 83:193-200.

- ↑ Nary DE, Froehlich AK, White GW. Accessibility of fitness facilities for persons with physical disabilities using wheelchairs. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2000; 6(1): 90-101.

- ↑ Boland M. Health promotion and health promotion needs assessment of people attending disability services in the HSE, East Coast Area. Doctorate of Medicine, University College Dublin. 2005

- ↑ 12. Fentem PH. Education and debate ABC of Sports Medicine: Benefits of exercise in health and disease. British Medical Journal. 1994;308:1291-1295.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Fullerton HD, Borckardt JJ, Alfano AP. Shoulder pain: A comparison of wheelchair athletes and nonathletic wheelchair users. Med. Sci. Sports Exec. 2003. Vol 35, No 12, pp. 1958-1961.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Curtis KA, Black K. Shoulder pain in female wheelchair basketball players. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1999. Vol, 29N No 4, pp. 225–231.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Increasing Physical Activity among Adults with Disabilities. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/pa.html

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Conchar L, Bantjes J, Swartz L, Derman W. Barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity: The experiences of a group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy. Journal of health psychology. 2014 Mar 6:1359105314523305.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Lauruschkus K, Nordmark E, Hallström I. “It’s fun, but…” Children with cerebral palsy and their experiences of participation in physical activities. Disability and rehabilitation. 2014 Feb 13;37(4):283-9

- ↑ Jones DB. “Denied from a lot of places” barriers to participation in community recreation programs encountered by children with disabilities in Maine: perspectives of parents. Leisure/Loisir. 2003 Jan 1;28(1-2):49-69.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC pediatrics. 2012 Jan 19;16(1):1.

- ↑ Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, de Blécourt AC, Geertzen JH, Dekker R. Barriers and facilitators of sports in children with physical disabilities: a mixed-method study. Disability and rehabilitation. 2015 Aug 28;37(18):1617-25.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC pediatrics. 2016 Jan 19;16(1):1.

- ↑ Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: barriers and facilitators. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004 Jun 30;26(5):419-25.

- ↑ Moore LL, Lombardi DA, White MJ, Campbell JL, Oliveria SA, Ellison RC. Influence of parents' physical activity levels on activity levels of young children. The Journal of pediatrics. 1991 Feb 28;118(2):215-9.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedlauruschkus2

References will automatically be added here, see <a href="Adding References">adding references tutorial</a>.

<span class="fck_mw_references" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="references" />

References for Images and Videos[edit | edit source]

Ben Chmielewski. Why do we play sports? 2016. [Picture] Available from: http://www.willistonian.org/why-do-we-play-sports/ [Accessed on 29th November]

Areadne. Towards the inclusive classroom: best practice [Picture]. 2015. Available from: http://www.areadne.eu/course/towards-the-inclusive-classroom-best-practice/ [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

Newsocracy. Wheelchair Basketball is a Game Changer for Mississippi Kids [Video]. 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRw3ztn24MY [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

Fiona Christie. Lothian Disability Badminton Club [Video]. 2013. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TXE4XKmijFw [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

Bank of Scotland. Muirfield Riding Therapy - Bank of Scotland Community Fund. [Video] 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xks5GfrUGC0 [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

TommyLawson. Thornton Rose Riding for the Disabled. [Video] 2011. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KizOl7FEi9Y [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

The Yard. The Yard DIY SOS short film [Video]. 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yzwg8RZhHAc [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

GDJ. Colourful Dancing Women Silhouette [Picture]. 2015. Available from: https://openclipart.org/detail/231890/colorful-dancing-women-silhouette [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]

IGN. Wii Sports Resort: Motion Plus Demo [Video]. 2009. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qcDjwRynyU [Accessed on 23rd November 2016]