Peripheral Sensitisation

Original Editor - Michelle Lee

Top Contributors - Michelle Lee, Shaimaa Eldib, Melissa Coetsee, Admin, Bruno Serra, Jo Etherton, Khloud Shreif and Mathius Kassagga

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Peripheral sensitisation refers to sensitisation of the nociceptive system in the periphery. It is characterised by an increased responsiveness and reduced threshold of nociceptive neurons to stimulation of their receptive fields.[1]

Physiological Mechanisms of Peripheral Sensitisation[edit | edit source]

Following an injury or tissue damage, sensitisation of the affected area occurs to help with healing by initiating behaviours that would prevent further injury (eg. guarding). The mechanisms that sensitise the nociceptive system operate both in the periphery (leading to primary hyperalgesia) and the central nervous system (leading to secondary hyperalgesia and allodynia).[1]

| Primary hyperalgesia | Secondary hyperalgesia | |

|---|---|---|

| Area affected | Localised to the area of tissue damage or nerve distribution | Occurs in healthy skin next to or further away from the injury site |

| Description | Heightened sensitivity to heat and mechanical stimulation in the area of damage | Heightened sensitivity to mechanical stimuli |

| Mechanism | Peripheral sensitisation | Central sensitisation |

Peripheral sensitisation is an increased sensitivity to an afferent nerve stimulus. This occurs after there has been an injury or cell damage to the area, and produces a flare response due to nociceptors producing lots of neuropeptides, which results in an increased sensitivity to heat and touch stimuli. If noxious stimuli are more painful than before, primary hyperalgesia is present. If non-noxious stimuli is now experienced as painful, primary allodynia is present. For example, a gentle stroke to the skin which before the injury is not painful but after is interpreted as pain.[4][5] The mechanisms responsible fot this response are explained below:

Up-regulation of existing receptors:[edit | edit source]

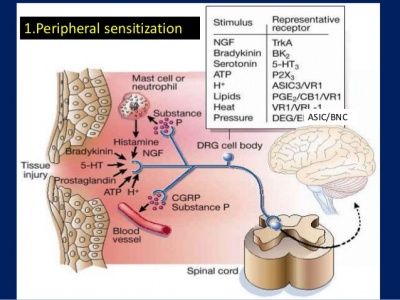

This can occur as a result of inflammation. Chemical mediators of inflammation (such as histamine, bradykinin, potassium) are released and can either stimulate the nociceptive receptors, making them depolarize, or sensitize them (bringing the membrane potential closer to the depolarization threshold). Receptors are sensitised by up-regulation of the ion-channels (influenced by the protein enzyme cascade), which makes them more sensitive to chemical mediators. This results in a lowered activation threshold (more sensitive to the same quantity of chemical mediators) and results in peripheral sensitisation.[4][6][7]The accumulation of 'inflammatory soup' of chemicals at the site of injury produces the characteristic signs of inflammation (redness, swelling and pain).[1]

In summary, the nociceptor terminals become more sensitive to the same quantity of the chemical mediators.

Up-regulation of new receptors:[edit | edit source]

The cell body which is located in the dorsal root ganglia sensory nerves produces protein channels and transmits signals to the nociceptive terminals. When there is inflammation present as described above, the Nerve Growth Factor is produced which transmits up to the cell body in the dorsal root ganglia. This then also stimulates the production of ions, which as described above, stimulates the receptors on the nociceptive terminals. Now the nociceptive terminals have a greater quantity of the 'chemical mediator' stimulating the sensation of pain more frequently.

The difference between central and peripheral sensitisation can be identified quite easily, as peripheral sensitisation becomes heat-sensitive whereas central sensitisation does not. Lorimer Moseley explains this in more detail in the video below.[4][8]

Clinical Findings[edit | edit source]

Comparison with Central Sensitisation[edit | edit source]

The difference between central and peripheral sensitisation can be identified quite easily, as peripheral sensitisation becomes heat-sensitive whereas central sensitisation does not. Lorimer Moseley explains this in more detail in the video below.[4][8]

What does this Mean?[edit | edit source]

Hypersensitivity following an injury is an important self-preservation mechanism, which allows the injured tissue to heal and to continuously warn/remind the brain to avoid further injury to this area. When this hypersensitivity becomes prolonged and develops into peripheral sensitisation be it through either; increased sensitivity to the chemical modulators or a decreased threshold to the stimulus provides the body with no benefit. peripheral sensitisation is important to identify in patients as this can have an impact on treatment and their experience of pain as assessment through touch or movement may stimulate an unexpected level of pain. Peripheral sensitisation manifests its symptoms similarly to central sensitisation. [11]

Management[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Johnson MI. The physiology of the sensory dimensions of clinical pain. Physiotherapy. 1997 Oct 1;83(10):526-36.

- ↑ Hsieh MT, Donaldson LF, Lumb BM. Differential contributions of A- and C-nociceptors to primary and secondary inflammatory hypersensitivity in the rat. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):1074-1083. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000151. PMID: 25760474; PMCID: PMC4535358.

- ↑ Pezet S, McMahon SB. Neurotrophins: mediators and modulators of pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci.. 2006 Jul 21;29:507-38..

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bolay H, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms of pain modulation in chronic syndromes. Neurology. 2002 Sep 10;59(5 suppl 2):S2-7.

- ↑ Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Peripheral and central sensitization in musculoskeletal pain disorders: an experimental approach. Current rheumatology reports. 2002 Aug 1;4(4):313-21.

- ↑ Staud R, Smitherman ML. Peripheral and central sensitization in fibromyalgia: pathogenetic role. Current pain and headache reports. 2002 Aug 1;6(4):259-66.

- ↑ Van Griensven H, Strong J, Unruh A. Pain: a textbook for health professionals. Churchill Livingstone; 2013 Nov 1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mizumura KA. Peripheral mechanism of hyperalgesia-sensitization of nociceptors. Nagoya journal of medical science. 1997 Nov 1;60:69-88.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Laree Draper. Lorimer Moseley Pain DVD Sensitivity to Heat, Peripheral Sensitization. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmQT5NgsUdc[last accessed 20/8/2021]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dr Matt & Dr Mike. Chronic Pain and Sensitisation. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rxl6c8UwmKs[last accessed 20/8/2021]

- ↑ Van Griensven H, Strong J, Unruh A. Pain: a textbook for health professionals. Churchill Livingstone; 2013 Nov 1.