Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour

Original Editor - Robin Tacchetti based on the course by Pam Versfeld

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Robin Leigh Tacchetti, Tarina van der Stockt, Ewa Jaraczewska, Kim Jackson and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

When newborn infants (0-4 weeks old) are awake and alert and lying on a firm surface they respond to visual and auditory events in the environment and actively engage in spontaneous movements of the limbs. The looking, listening and moving provides opportunities for linking what they do to what is seen, heard and felt, creating the perception-action loops that are the basis for making the shift from spontaneous exploratory movements to intentional, goal directed actions that allow the infant to interact with people, things and events in their environment.[1]

Limb Movement Synergies at Birth[edit | edit source]

The multi-segmented structure of the body provides the basis for producing the varied movement patterns seen in human actions. To simplify control of the many degrees of freedom inherent in a multi-segmented body, spontaneous infant movements are constrained and organised into synergies.[2]

- Lower limb synergy pattern includes intralimb coupling of

- hip flexion, knee flexion and dorsiflexion

- hip extension and knee extension

- Upper limb synergy pattern includes a combination of

- shoulder and elbow extension with extension of the fingers and wrist;

- flexion of the elbow with finger flexion.[3]

These whole body movements, called general movements or GMs, are complex and involve the entire body, notably arm, leg, neck, and trunk movements in variable sequences.[3]

Over the first few months as the infant explores different ways of interacting with the environment and as the frontal motor areas become more active, the strong intralimb coupling lessens as movement are adapted to allow for effective interaction with the environment. [1]

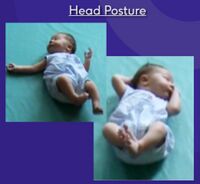

Head Posture[edit | edit source]

- In supine the newborn's head is mostly rotated to one side, often with a preference for a particular side, usually to the right.[4] The reason for this tendency is unclear.

- A prominent feature of head rotation in the first two months is the tendency for rotation to be coupled with neck extension and lateral flexion to the opposite side, which is a reflection of the balance in activity between the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles and deep neck flexor muscle activity.[5]

- Over the first few weeks the infant learns to turn the head to the midline, and can sustain the position briefly, especially when supported by visual attention to an interesting person, object or event.[1]

- Typically the head is held in the mid-position for brief periods of time when the infant is actively moving the limbs or is distressed.[6]

- Over the next few weeks the infant will develop the the bilateral antigravity neck muscle strength and control needed to counteract the force of gravity (which creates a turning moment acting on the Center of Gravity (COG) of the head) and maintain the head in midline for longer periods of time.

Movements[edit | edit source]

Newborn general movements are described as writhing until about 2 months old. Voluntary, goal-directed functional movements replace spontaneous movement around 3 months old. Infants aged between 3 and 5 months will begin to reach out for objects.[7]

Newborn lower limb posture assumes a flexed posture. The hip and knee flexors present with increased tone due to the tight space in utero. Restriction in hip extension is referred to as hip flexion contracture. Upper limb posture for newborns is slight external rotation, elbow flexion with the hands slightly open. Spontaneous movements of the arm bring the hand into contact with the face.[3]

Synergies[edit | edit source]

Muscle synergies, the activation of muscle groups, are the basis for newborn motor control. As infants age and become toddlers and then adults, muscle synergies increase and become more complex.[8] Productive movement implementation can be achieved by combining muscle synergies.[9] Research shows that muscle synergies are innate, but acquiring new tasks may demand fine-tuning of the early synergies.[10] Pam Versfeld[3] describes infant upper and lower limb synergies as follows:

- Lower limb synergy pattern: hip flexion, knee flexion and dorsiflexion; hip extension, knee extension.

- Upper limb synergy pattern: shoulder, elbow extension with extension of the fingers and wrist; flexion of the elbow with finger flexion.[3]

Combining muscle synergies is valuable to development, skilled motor tasks and postural control.[9]

Posture[edit | edit source]

Good postural control enables infants to perform a range of tasks that serve a function in motor development.[11] Movement of the extremities follows sufficient postural control.[12] Varying postures facilitate or reduce physical interactions with objects, caregivers and the environment.[12] [13] When infants are prone, one hand is needed to lift the torso, leaving only one hand to manipulate objects.[12] Having to focus on balance will limit object manipulations.[13] Contrastingly, in sitting the infant is free to use both hands to explore and play increasing possibilities of action.[12] Continuous trial and error learning exploration increases the infant’s ability to choose the best motor strategies.[14] Due to visual and social benefits, infants have a preference for upright postures.[14] As infants age and with increased experiences, more adaptive postural responses emerge. One study demonstrated that even 3-5-month-olds can perform task-specific standing by adjusting their posture. The participants in this study stood with a stiff posture which is a common theme when learning a new motor skill. With continued trial and error, freezing posture is replaced by more flexibility, which in turn increases postural control.[14]

Visual Perception[edit | edit source]

Moving eyes in the direction of a target is referred to as visual perception. Pointing eyes to a specific location involves coordinating the body, head and eyes to the target. Newborns who lack head control can only view whatever is in their line of vision. Young infants track larger targets that move in predictable ways. Smaller and faster targets can be tracked once the infant has had many months of practice.[12]

Imitation[edit | edit source]

Imitating the action of others is a powerful learning tool for infants.[15] [16] Through imitation of behaviour, postures, vocalisations and action on objects they acquire new knowledge.[15] Cause and effect, properties of objects and the actions of others are all learning skills infants gain through imitation. As they imitate others, they learn about themselves, their abilities, similarities to others and their own characteristics. Research shows that who and what when is imitated and when is chosen by the infant in a deliberate and selective manner. In addition, infants choose trustworthy and friendly models to imitate. Studies show that infants will less likely imitate a behaviour linked to negative emotion.[16] Very shortly after birth, infants will imitate adult behaviour. Pam Versfeld[3] describes some ways infants mimic others including: mouth opening, tongue protruding, sequential finger movements and head-turning. The video below by Lund University demonstrates how babies mimic others:

Reaching[edit | edit source]

Good postural support enables infants to interact within their environment by reaching and grasping.[12] [18] Reaching supersedes grasping.[18] Initially, reaching movements are jerky and infants may overshoot or undershoot the target. A 3-month-old will typically bat at objects because they do not have the hand control necessary for grasping. When infants begin using their hands to grasp, they tend to bring the object to their face for mouthing or looking. Manual grasping skills advance to squeezing, rotating and transferring objects from hand to hand.[12] Reaching and grasping objects enable new social interactions between the infant and caregiver.[18] The following video by Pathways.org details typical and nontypical motor skills in a 2 month old:

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Understanding Newborn Behaviour

- https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/itf09percmotdev.asp

- Motor Control and Learning

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Versfeld, P. SfA Infant Perceptual Motor Development

- ↑ Von Hofsten C. Mastering reaching and grasping: The development of manual skills in infancy. InAdvances in psychology 1989 Jan 1 (Vol. 61, pp. 223-258). North-Holland.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Versfeld, P. Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour Course. Physioplus. 2021

- ↑ Rönnqvist L, Hopkins B. (1998) Head position preference in the human newborn: a new look. Child Dev. 69(1):13-23.

- ↑ Bly L, Ariz TN. Motor skills acquisition in the first year, an illustrated guide to normal development.

- ↑ Cornwell, K. S., Fitzgerald, H. E., & Harris, L. J. (1985). On the state‐dependent nature of infant head orientation. Infant Mental Health Journal, 6(3), 137-144.

- ↑ Ouss L, Le Normand MT, Bailly K, Leitgel Gille M, Gosme C, Simas R, Wenke J, Jeudon X, Thepot S, Da Silva T, Clady X. Developmental trajectories of hand movements in typical infants and those at risk of developmental disorders: an observational study of kinematics during the first year of life. Frontiers in psychology. 2018 Feb 19;9:83.

- ↑ Booth AT, Van Der Krogt MM, Harlaar J, Dominici N, Buizer AI. Muscle synergies in response to biofeedback-driven gait adaptations in children with cerebral palsy. Frontiers in physiology. 2019 Sep 27;10:1208.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Saito H, Yokoyama H, Sasaki A, Kato T, Nakazawa K. Flexible recruitments of fundamental muscle synergies in the trunk and lower limbs for highly variable movements and postures. Sensors. 2021 Jan;21(18):6186.

- ↑ Cheung VC, Cheung BM, Zhang JH, Chan ZY, Ha SC, Chen CY, Cheung RT. Plasticity of muscle synergies through fractionation and merging during development and training of human runners. Nature communications. 2020 Aug 31;11(1):1-5.

- ↑ Pin TW, Butler PB, Cheung HM, Shum SL. Segmental Assessment of Trunk Control in infants from 4 to 9 months of age-a psychometric study. BMC paediatrics. 2018 Dec;18(1):1-8.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Adolph KE, Franchak JM. The development of motor behavior. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2017 Jan;8(1-2):e1430.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Thurman SL, Corbetta D. Changes in posture and interactive behaviors as infants progress from sitting to walking: a longitudinal study. Frontiers in psychology. 2019 Apr 12;10:822.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sigmundsson H, Lorås HW, Haga M. Exploring task-specific independent standing in 3-to 5-month-old infants. Frontiers in psychology. 2017 Apr 28;8:657.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jones SS. Infants learn to imitate by being imitated. InProceedings of the International Conference on Development and Learning: The Tenth International Conference on Development and Learning 2006 Jun 3. Indiana University Bloomington, IN.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Meltzoff AN, Marshall PJ. Human infant imitation as a social survival circuit. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2018 Dec 1;24:130-6.

- ↑

Lund University: Babies know when you imitate them - and like it. 2020. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63u7l5-x1Hk&t=4s

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lobo MA, Harbourne RT, Dusing SC, McCoy SW. Grounding early intervention: physical therapy cannot just be about motor skills anymore. Physical therapy. 2013 Jan 1;93(1):94-103

- ↑ Pathways: 2 Month Old Baby Typical & Atypical Development Side by Side. 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0cErYu3A8Q&t=1s