Multidimensional Nature of Pain

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

Define acute and chronic pain terms of a multidimensional pain experience.

- Anatomical, physiological, and psychological basis of pain and pain relief, including pain as an 'output' from the brain

- Definition of pain and evidence of the multidimensional nature of the pain experience e.g. social and psychological infleuncing factors

Original Editor - Alberto Bertaggia.

Top Contributors - Alberto Bertaggia, Nina Myburg, Admin, Kim Jackson, Michelle Lee, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Lauren Lopez, Jess Bell and Jo Etherton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A definition of pain is provided by the International association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as follows[1]:

"An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage"

Pain is always subjective and everyone learns the use of this word through experiences related to injury in early life.

It is a sensation in a part or parts of the body, but it is also always unpleasant and therefore also emotional.

Even in the absence of tissue damage or any likely pathophysiological cause, people still report pain; usually this happens for psychological reasons. In these cases, it is challenging to distinguish whether their experience arise from a damaged tissue or not, based only upon the subjective report[2].

It is important to underline that activity induced in the nociceptor and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain[2], which is always the output of a widely distributed neural network in the brain rather than one coming directly by sensory input evoked by injury, inflammation, or other pathology[3].

In the following video Karen D. Davis tries to explain why do some people react to the same painful stimulus in different ways.

Relevant anatomy and physiology[edit | edit source]

Nociceptors[edit | edit source]

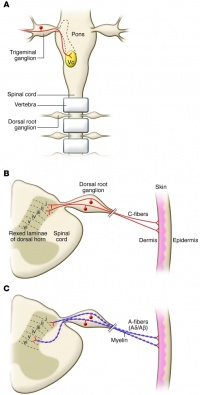

Nociceptors (from the latin nocere = to hurt) are sensory receptors which detect signals from damaged tissue or the threat of damage and indirectly also respond to chemicals released from the damaged tissue. There are free nerve endings present in many types of tissues, and cell bodies located in the dorsal root ganglions or in the cranial nerve ganglia.

Nociceptors have unmyelinated (C-fiber) or thinly myelinated (A-fiber) axons[4]. C-fibers support conduction velocities of 0.4–1.4 m/s, while A-fibers support conduction velocities of approximately 5–30 m/s[5].

Nociception

[edit | edit source]

Nociception is a mechanism which comprises the processes of transduction, conduction, transmission and perception[6].

- Transduction is the conversion of a noxious thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimulus into electrical activity in the peripheral terminals of nociceptor sensory fibers. This process is mediated by specific receptor ion channels expressed only by nociceptors.

- Conduction is the passage of action potentials from the peripheral terminal along axons to the central terminal of nociceptors in the central nervous system.

- Transmission is the synaptic transfer and modulation of input from one neuron to another.

- Projection neurons in the dorsal horn transfer nociceptive input to the brainstem, hypothalamus, and thalamus and then, through relay neurons, to the cortex. Here is where perception occur as a subjective experience.

Types of pain classification[edit | edit source]

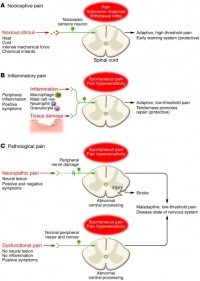

Based upon the works of Woolf[6][7], this is a useful types of pain classification:

- Nociceptive pain. This kind of pain is concerned with the sensing of noxious stimuli and is a high-threshold pain only activated in the presence of intense stimuli. It has a protective role requiring immediate attention and responses (i.e. withdrawal reflex).

- Inflammatory pain. This second kind of pain is important to promote protection and healing of the injured tissues by creating an enviroment which suggests avoidance of movement and stress of the body parts. This is made possible by activation of the immune system causing inflammation.

- Pathological pain. This type of pain is uncoupled from noxious stimulii and even from tissue damage, it is not protective, and results from abnormal functioning of the nervous system (peripheral or central). To note, this is a low-threshold pain. This time pain is not a symptom, but rather a disease itself. It occurs with peripheral sensitization and central sensitization.

Acute and chronic pain

[edit | edit source]

Acute pain is caused by a noxious stimuli ad is mediated by nociception. It has early onset and serve to prevent tissues damages. It is also useful to learn to avoid threat of damage, because certain categories of noxious stimulii become linked to the sensation of pain. This is why this type of pain is defined as adaptive, it helps to survive and to heal[6]

Chronic pain is pain continuing beyond 3 months or after healing is complete[2]. It may arise as a consequence of tissue damage or inflammation or have no identified cause[8]. It can affect a specific body part (i.e. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), low back pain (LBP), pelvic pain) or be widespread (i.e. fibromyalgia). Chronic pain is a complex condition embracing physical, social and psychological factors, consequently leading to disability, loss of independence and poor quality of life (QoL)[9].

Psychological factors in pain

[edit | edit source]

Anxiety

[edit | edit source]

Health anxious individuals form dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs about symptoms and disease based on past experiences and become health anxious when these dysfunctional scheme are triggered by critical incidents[10]. Moreover, they will have a tendency to misinterpret somatic information as catastrophic and personally threateningCite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ IASP Taxonomy - IASP [Internet]. [cited 2016 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Pain

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. IASP Press; 1994. 248 p.

- ↑ Melzack R. Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. J Dent Educ. 2001 Dec;65(12):1378–82.

- ↑ McCleskey EW, Gold MS. Ion channels of nociception. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:835–56.

- ↑ Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J Clin Invest. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3760–72.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Woolf CJ, American College of Physicians, American Physiological Society. Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Mar 16;140(6):441–51.

- ↑ Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain? J Clin Invest. 2010 Nov 1;120(11):3742–4.

- ↑ Chronic Pain: Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment | NIH MedlinePlus the Magazine [Internet]. [cited 2016 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/magazine/issues/spring11/articles/spring11pg5-6.html

- ↑ Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006 May;10(4):287–333.

- ↑ Hadjistavropoulos HD, Hadjistavropoulos T, Quine A. Health anxiety moderates the effects of distraction versus attention to pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000 May;38(5):425–38.