Management of Ankle Sprains

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Ankle sprains are considered one of the most frequent traumatic injuries. Yeung et al. (1994)[1] conducted an epidemiological study of unilateral ankle sprains and reported that the dominant leg is 2.4 times more vulnerable to sprain than the non-dominant one.[1] There were reports proposing that the greater the level of plantar flexion the higher the likelihood of a sprain.[2] Conservative treatment is the common approach to an ankle injury. The prognosis is generally good, but there is a number of risk factors influencing the full recovery.[3] These factors, when identified early, can change the treatment protocol to a more aggressive approach.[3]

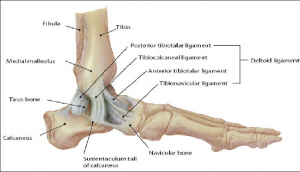

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lateral Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

The literature suggests that 85% of ankle sprains involve lateral ligaments.[4] The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) of the lateral ankle ligament complex is the most frequently damaged when a lateral ankle sprain occurs. Their anatomical location and the mechanism of sprain injury mean that the calcaneofibular (CFL) and posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL) are less likely to sustain damaging loads.

Medial Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

On the medial side the strong, deltoid ligament complex [posterior tibiotalar (PTTL), tibiocalcaneal (TCL), tibionavicular (TNL) and anterior tibiotalar ligaments (ATTL)] is injured with forceful "pronation and rotation movements of the hindfoot".[5]

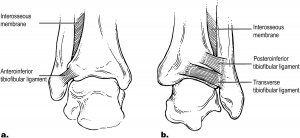

Syndesmotic Ankle Sprain[edit | edit source]

The stabilising ligaments of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis are the anterior-inferior, posterior-inferior, and transverse tibiofibular ligaments, the interosseous membrane and ligament, and the inferior transverse ligament. A syndesmotic ankle sprain occurs with combined external rotation of the leg and dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Risk Factors and Outcome[edit | edit source]

Predisposing factors are the risk factors for ankle sprains.[3] Identifying risk factors helps the clinician to choose the most appropriate treatment regimen given the fact that these risk factors have a significant impact on the patient's recovery.[3] They are divided into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic risk factors for outcome prediction include:[5]

- Age and biological sex: female athletes have a 25% greater risk of suffering from a grade I ankle sprain[6]

- Height and weight: an increase in height or weight proportionally increases the risk of a sprain due to an increased magnitude of inversion torque.

- The grade of injury

- Functional status

- Associated injury, especially previous sprains

- Limb characteristics: limb dominance, anatomic foot type and foot size, joint laxity, anatomic alignment, range of motion of the ankle-foot complex including abnormalities in foot biomechanics such as pes planus, pes cavus, and increased hindfoot inversion were risk factors for lower extremity overuse injury.[7]

- Muscle strength

- Posture, particularly postural sway: increased sway leads to a 7-fold increase in ankle sprains. [8]

Extrinsic risk factors for outcome prediction include:

- Level of competition: the higher the level, the number of ankle sprains increases.

- Ankle bracing or taping: introducing this intervention early on can lower the incidence of ankle sprains.

- Shoe type

- Lack of warm-up stretching

- Landing technique after the jump.[4]

In summary, the following prognostic factors suggest good clinical outcomes after foot and ankle injury: younger age, low-grade sprain, low activity level, good functional status, good neuromuscular function, no associated injury.[3] Long lasting symptoms with functional limitations can be predicted based on the presence of systemic laxity, joint geometry, limb and foot malalignment, re-sprain, and multi-ligament injury.[3]

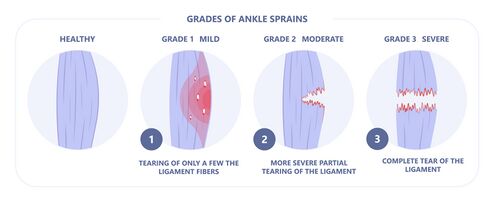

Classification Grading Systems[edit | edit source]

The severity of the ligament injury is defined by grade I, II, or III of the ankle sprain. There is also a functional grading that divides ankle sprains into mild, moderate and severe sprains.

- Grade I represents a microscopic injury without stretching of the ligament.

- Grade II has macroscopic stretching, but the ligament remains intact or with a more severe sprain it can be partially torn.

- Grade III is a complete rupture of the ligament.

Mild and moderate sprains are usually grades I. A mild sprain is characterised by the patient's inability to run and jump, difficulty with stair climbing, and presence of discomfort. In this type of sprain, the ligaments are intact.

Moderate sprains require support to walk, there is the presence of significant pain, swelling and bruising.

Severe sprains are grade III sprains where weight bearing is impossible, pain is high and the patient needs further testing towards ankle fracture. Immobilisation is usually required for 10 or more days and surgery often becomes the treatment of choice.

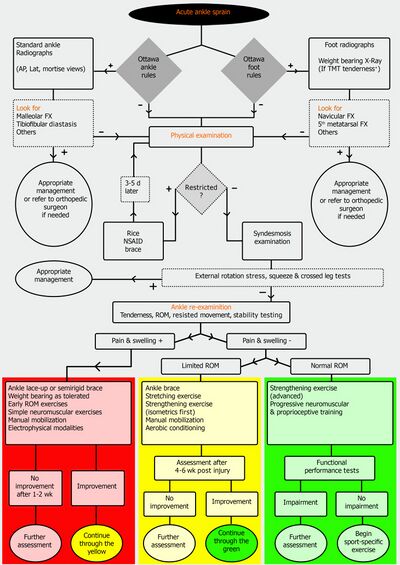

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Clinical assessment including Ottawa Ankle and Foot Rules can be supported by other investigations including:

X-ray: allows to rule out an ankle or mid-foot fracture within 7 days after the injury. Testing in a weight-bearing position is recommended.

Ultrasound: is considered a good diagnostic tool for ligamentous injury, functional impairments, and joint instability. Diagnostic accuracy depends on the skills of the personnel performing the test and the quality of the equipment. Ultrasound is an investigation less sensitive than an MRI in the diagnosis of an acute ligament injury.[9][10]

MRI: the gold standard for investigating intra-articular damage.[10] Assists with a diagnosis of the acute tears of the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments, however, false-positive findings can be challenging for the referring physician. MRI is not considered a routine investigation in the acute ankle injury because of the high cost of the test, limited accessibility, and high incidence of this type of injury. MRI can be very helpful in the diagnosis of suspected additional injuries including syndesmotic injury, tendon pathologies or in case of chronic ankle instability requiring further investigation. [10]

CT scan: is not routinely ordered as a diagnostic tool in ankle sprain injury. The recommendation is based on each case individually.

Management[edit | edit source]

"The earlier musculoskeletal rehabilitation care started after an ankle sprain, the lower the likelihood of recurrence and the downstream ankle-related medical costs incurred".[11]

The following are the guidelines proposed by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) and published in 2013[9]. The second guidelines are taken from a 2020 publication by the World Journal of Orthopaedic (WJO).[4] Category A in NATA publication means that the recommendations are based on "consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence", and category B is defined by " inconsistent and limited- quality patient-oriented evidence". Halabchi F and Hassabi M (2020) in their guidelines published in the WJO, use clinical evidence levels 1, 2 and 3 to support their recommendations:

Level 1: evidence is obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial.

Level 2: evidence comes from a meta-analysis of all relevant randomised controlled trials.

Level 3: evidence is obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomisation.

Acute Phase[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation Goals:

- Pain reduction. Activities should be performed NICE and EASY, eg., external support worn up to one year post-injury.[12]

- Progressive return to motion. Follow POLICE acronym (Protection, Optimal Loading, Integrated Control Exercises).[12]

- Restoring body self-perception. Performed tasks should be purposeful, progressive (from simple to complex), and relevant. [12]

RICE[edit | edit source]

In the acute phase of ankle sprain injury, the treatment of choice is RICE, including Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation.

- Rest: treatment protocol includes elevation of the injured leg 15-25 cm above the level of the heart to assist with lymphatic drainage.

- Ice: is considered a routine therapy for 3-7 days after the injury for pain and swelling reduction. There is limited evidence in symptoms reduction associated with an ankle sprain (Level 1) and no evidence in reducing swelling and decreasing pain (Level 2).

- Compression: is applied for management of swelling and for quality of life improvement. Compression modalities include elastic bandaging or splints. The effectiveness of compression has limited support in research (Level 2).

- Elevation: No control trials were conducted to support the effectiveness of elevation in the treatment of ankle sprains.

Immobilisation[edit | edit source]

- Grade I and II ankle sprain: recommendations include early mobilisation and functional support allowing functional rehabilitation (level 1, category A).

- Grade III ankle sprain: 10 days of immobilisation using a below-knee cast or rigid brace (level 2, category B), followed by controlled therapeutic exercises (category B).

- Immobilisation in a form of ankle brace allow loading and protection of the damaged tissue (category A, level 2)[13] and it should be used for a minimum of 6 months following the moderate or severe sprain. A semi-rigid brace or lace-up brace is better than an elastic bandage (level 1) and more effective than rigid or elastic tape (level 2). This type of bracing is recommended for individuals with a prior history of ankle sprains.

- Kinesio Taping may not provide sufficient mechanical support for unstable joint(level 1).

- There is a lack of randomised controlled trials in the initial management for medial or syndesmotic sprains with immobilisation. [10]

- The choice of support depends on the severity of the injury.

Modalities[edit | edit source]

- Electrical stimulation: no evidence in the literature supporting the use of modality in pain or oedema reduction (level 1).

- Laser: no evidence supporting the use of laser for pain and oedema reduction (level 1).

- Therapeutic ultrasound: no effect on pain, oedema, function and return to play (level 1). The use of ultrasound for the management of acute ankle sprains is not indicated.[13]

- Shortwave diathermy: no evidence to use in the management of ankle sprains (level 2).

Weight Bearing[edit | edit source]

Early protected weight-bearing up to 2 weeks for all grade sprains assists with [14]

- swelling reduction

- restoration of the normal range of motion

- return to normal activity

- preventing mechanical instability long-term

Manual Therapy[edit | edit source]

Manual techniques included in the management of acute ankle sprains are anterior to posterior talocrural glides and talocrural distraction in the neutral position.[15] In addition soft tissue massage and manual lymphatic drainage techniques are recommended. Dorsiflexion passive range of motion can be performed in both positions of weight-bearing or non-weight-bearing.[4]

The application of manual therapy resulted in:

- pain reduction (level 1)[16]

- reduction of stiffness

- improvement in the ankle dorsiflexion(level 1, category B)

- improvement in the stride length

- better proprioceptive awareness

- functional recovery (level 2, category B)

Exercises[edit | edit source]

Therapeutic exercises are considered the main component of the rehabilitation program for the acute ankle sprain, however, no specific content and training volume has been determined. [4]The expected results of performing exercises are: reduction in recurrent injuries, preventing ankle instability, shortening a recovery time, improvement in self-reported function (level 1).

Exercises should be supervised (level 1), or based on the conventional program (level 2) and they should include the following:

- Range of motion exercises (category B)

- Stretching exercises (category B): start with an open chain in all planes, dorsiflexion stretch with upper extremity assist, progress to a closed chain. Heel cord stretching should be initiated as soon as possible.

- Strengthening exercises (category B): start immediately for grade I and II sprains, may need to be postponed for grade III sprain, inversion and eversion of the ankle should be minimised. The protocol should include slow movements performed within pain limits and high repetitions (Example: 2-4 sets x 10 repetitions). Start with isometrics in frontal and sagittal planes, progress to isotonic resistive exercises with weights, elastic bands or manual resistance, add movement in all planes.

- Neuromuscular reeducation and proprioceptive exercises (level 2)

Neuromuscular Reeducation[edit | edit source]

Neuromuscular reeducation activities performed in the acute ankle sprain include:

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) exercises. The use of PNF resulted in significant improvement in ankle functional outcome measures, including Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT). Implementation of neuromuscular training within the first week of injury resulted in pain-free higher activity level and swelling reduction (level 1).

- Balance training. This type of activity should be performed in all stages of rehabilitation (category A).[9]

Subacute Phase[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation goal:

- To design a return-to-work schedule with activity limitations and participation restrictions.

In this phase of the rehabilitation program for the ankle sprain the focus is on:

- Neuromuscular training programs include balance and proprioception tasks with periods of destabilisation during exercises. Standing balance exercises initiated on one leg without a board should be incorporated and progressed towards maintaining balance on an unstable surface with both and then the injured foot and with the slow removal of hands support. The same sequence is repeated on the BAPS board.

- Inversion and eversion range of motion exercises.

- Strengthening of the proximal muscles of the hip and trunk to assist with the re-injury rate reduction

- Exercises with sport-specific perturbation for high-performance athletes finished by full-speed planned movement drills and unilateral jumps.

- Occupational training and/or work hardening program.[13]

Chronic Phase[edit | edit source]

Multi-intervention injury-prevention program should begin in the acute phase and continue through the chronic phase for at least 3 months after the ankle sprain.

Rehabilitation goals :

- Reduce the risk of the ankle re-injury

- Restore full, painless range of motion

- Return to sports/work/activities without recurrent symptoms

The program consists of :

- Balance and neuromuscular control (category A)

- Sport-specific training. Examples include plyometric training with jumping manoeuvres for a volleyball player; running and cutting drills for a soccer player. Time to return to sport will vary.[10]

- Application of a brace or tape during sport-specific training

Important information on chronic ankle instability (CAI) you can find here

Resources[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Ankle Instability: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/69414

Mayo Clinic: Sprained ankle: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sprained-ankle/symptoms-causes/syc-20353225

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yeung MS, Chan KM, So CH, Yuan WY. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. Br J Sports Med. 1994 Jun;28(2):112-6.

- ↑ Wright IC, Neptune RR, van den Bogert AJ, Nigg BM. The influence of foot positioning on ankle sprains. J Biomech. 2000 May;33(5):513-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Ferreira JN, Vide J, Mendes D, Protásio J, Viegas R, Sousa MR. Prognostic factors in ankle sprains: a review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020 Jun 1;5(6):334-338.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Halabchi F, Hassabi M. Acute ankle sprain in athletes: Clinical aspects and algorithmic approach. World J Orthop. 2020 Dec 18;11(12):534-558.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beynnon BD, Murphy DF, Alosa DM. Predictive Factors for Lateral Ankle Sprains: A Literature Review. J Athl Train. 2002 Dec;37(4):376-380.

- ↑ Hosea TM, Carey CC, Harrer MF. The gender issue: epidemiology of ankle injuries in athletes who participate in basketball. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):45-9.

- ↑ Kaufman KR, Brodine SK, Shaffer RA, Johnson CW, Cullison TR. The effect of foot structure and range of motion on musculoskeletal overuse injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1999 Sep-Oct;27(5):585-93.

- ↑ McGuine TA, Greene JJ, Best T, Leverson G. Balance as a predictor of ankle injuries in high school basketball players. Clin J Sport Med. 2000 Oct;10(4):239-44.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kaminski TW, Hertel J, Amendola N, Docherty CL, Dolan MG, Hopkins JT, Nussbaum E, Poppy W, Richie D; National Athletic Trainers' Association. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: conservative management and prevention of ankle sprains in athletes. J Athl Train 2013; 48: 528-545

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Chen ET, McInnis KC,Borg-Stein J. Ankle Sprains: Evaluation, Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2019 (June);18(6): 217-223.

- ↑ Rhon DI, Fraser JJ, Sorensen J, Greenlee TA, Jain T, Cook CE. Delayed Rehabilitation Is Associated With Recurrence and Higher Medical Care Use After Ankle Sprain Injuries in the United States Military Health System. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Dec;51(12):619-627.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 McKeon PO, Donovan L. A Perceptual Framework for Conservative Treatment and Rehabilitation of Ankle Sprains: An Evidence-Based Paradigm Shift. J Athl Train. 2019 Jun;54(6):628-638.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Martin RL, Davenport TE, Fraser JJ, Sawdon-Bea J, Carcia CR, Carroll LA, Kivlan BR, Carreira D. Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Lateral Ankle Ligament Sprains Revision 2021. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Apr;51(4): CPG1-CPG80.

- ↑ Knapik DM, Trem A, Sheehan J, Salata MJ, Voos JE. Conservative Management for Stable High Ankle Injuries in Professional Football Players. Sports Health. 2018 Jan/Feb;10(1):80-84.

- ↑ Loudon JK, Reiman MP, Sylvain J. The efficacy of manual joint mobilisation/manipulation in the treatment of lateral ankle sprains: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Mar;48(5):365-70.

- ↑ Cleland JA, Mintken PE, McDevitt A, Bieniek ML, Carpenter KJ, Kulp K, Whitman JM. Manual physical therapy and exercise versus supervised home exercise in the management of patients with inversion ankle sprain: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(7):443-55.

- ↑ The Physio Channel. Ankle Talocrural Joint Mobilisation. 2019. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eJOwsFeLdik [last accessed 29/01/2022]

- ↑ Physical Therapy Nation. Talocrural Distraction Manipulation. 2013.Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahpRMlOdkjM [last accessed 29/01/2022]

- ↑ Sports Injury Clinic.Sports Massage - Ankle Sprain. 2010. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDIYHxjiUd0 [last accessed 29/01/2022]