Lifestyle Medicine and Office Ergonomic Strategies for Managing Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

(added videos) |

(added citations for videos) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

The COVID-19 global pandemic has changed the way many people work, especially those who work in an office setting. According to the US census bureau, more than a third of U.S. households reported a family member was working from home more frequently than before the pandemic.<ref>United States Census Bureau. Working from home during the pandemic. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/working-from-home-during-the-pandemic.html (accessed 19/12/2021).</ref> Working from home may contribute to an increase in musculoskeletal discomfort and pain due to a lack of resources for proper ergonomic setup and assessment.<ref>Salajar R, Yulianto A. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Revi-Salajar/publication/350090312_Hazard_Identification_and_Risk_Assessment_of_Human_FactorsErgonomics_HFE_While_Working_from_Home/links/6050869d299bf1736746aa41/Hazard-Identification-and-Risk-Assessment-of-Human-Factors-Ergonomics-HF-E-While-Working-from-Home.pdf Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment of Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E) While Working from Home.] American Journal of Engineering Research. 2021;10(2):140-144.</ref> A study published in 2020 by Pekyavas found that in the transition to a home office environment, approximately 86% of the participants work at a desk set up and 65% and spent 3-8 hours/day working in that environment. Approximately half reported LBP as their most painful musculoskeletal complaint, followed by shoulder pain (44.8%), and knee pain (35.6%).<ref>PEKYAVAŞ NÖ, PEKYAVAS E. [https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1212407 Investigation of The Pain and Disability Situation of The Individuals Working" Home-Office" At Home At The Covid-19 Isolation Process.] International Journal of Disabilities Sports and Health Sciences. 2020;3(2):100-4.</ref> | The COVID-19 global pandemic has changed the way many people work, especially those who work in an office setting. According to the US census bureau, more than a third of U.S. households reported a family member was working from home more frequently than before the pandemic.<ref>United States Census Bureau. Working from home during the pandemic. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/working-from-home-during-the-pandemic.html (accessed 19/12/2021).</ref> Working from home may contribute to an increase in musculoskeletal discomfort and pain due to a lack of resources for proper ergonomic setup and assessment.<ref>Salajar R, Yulianto A. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Revi-Salajar/publication/350090312_Hazard_Identification_and_Risk_Assessment_of_Human_FactorsErgonomics_HFE_While_Working_from_Home/links/6050869d299bf1736746aa41/Hazard-Identification-and-Risk-Assessment-of-Human-Factors-Ergonomics-HF-E-While-Working-from-Home.pdf Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment of Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E) While Working from Home.] American Journal of Engineering Research. 2021;10(2):140-144.</ref> A study published in 2020 by Pekyavas found that in the transition to a home office environment, approximately 86% of the participants work at a desk set up and 65% and spent 3-8 hours/day working in that environment. Approximately half reported LBP as their most painful musculoskeletal complaint, followed by shoulder pain (44.8%), and knee pain (35.6%).<ref>PEKYAVAŞ NÖ, PEKYAVAS E. [https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1212407 Investigation of The Pain and Disability Situation of The Individuals Working" Home-Office" At Home At The Covid-19 Isolation Process.] International Journal of Disabilities Sports and Health Sciences. 2020;3(2):100-4.</ref> | ||

These two short videos provide information on the effects prolonged sitting has on the body. | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|0kU2tNCYTsg|250}} </div> | <div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|0kU2tNCYTsg|250}}<ref>Youtube. Pain from Sitting Too Long? The Anatomy behind Prolonged sitting. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kU2tNCYTsg (accessed 19/12/2021).</ref> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|wUEl8KrMz14|250}} </div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> {{#ev:youtube|wUEl8KrMz14|250}}<ref>Youtube. TED ED Why sitting is bad for you. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUEl8KrMz14 (accessed 19/12/2021).</ref> | |||

</div> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 06:25, 20 December 2021

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Carin Hunter, Tony Lowe and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Back pain is a common complaint among persons who spend an extended amount of time in any one position. When considering the typical office worker, this is often a seated position. A sedentary lifestyle is becoming more common as an increasing number of people spend an extended amount of time seated for both work and leisure time. A 2019 study published in Applied Ergonomics found an association between chronic low back pain (LBP) and prolonged static sitting posture.[1]

LBP is the third highest cause of self-perceived disability[2] and causes major burdens on individuals, employers and society[3] identifying risk factors is of high importance when creating an appropriate prevention plan. For physiotherapists this often involves the use of ergonomics and postural analysis.

Ergonomics and Whole-Person Health[edit | edit source]

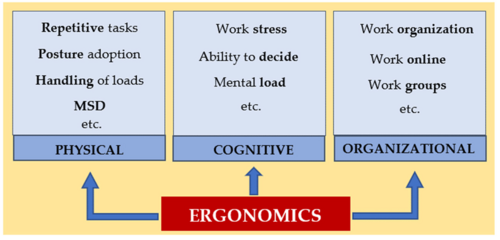

Ergonomics: the science concerned with fitting a job to a person’s anatomical, physiological, and psychological characteristics in a way that enhances human efficiency and well-being.” [4][5]

This article will limit the discussion on ergonomics to the office setting, it should be noted that ergonomic assessments can be completed in any setting a person must perform work activities. The term ergonomics is interchangeable with human factors or can be combined with human factors and ergonomics (HFE).[6]

Physiotherapists are often involved with physical ergonomic assessments of workplace setups, they assess and make recommendations to improve a person’s anatomical or physiological functioning by adjusting the positions they hold their body while working to minimize risk for injury, minimizing repetitive motions. The human component of a work system must be considered during the assessment, it is important for the physiotherapist to consider whether:

- equipment is usable

- tasks are compatible with a person's ability and training

- the environment is comfortable and appropriate for the assigned task

- the work system takes a person's need for social and economic needs.[7]

Please review the following video of a physiotherapist quickly demonstrating a seated office computer assessment.

Other factors taken into consideration during a physical ergonomic assessment include:

- Worker health

- Working postures

- Handling materials

- Repetitive movements

- Work-related musculoskeletal disorders

- Workplace layout

- Equipment design

- Safety [9]

Ergonomics looks at more than just the physical functioning and user positioning of a work system. According to the International Ergonomics Association, ergonomics is a "multi-disciplinary, user-centric integrating science. The issues HFE addresses are typically systemic in nature; thus HFE uses a holistic, systems approach to apply theory, principles, and data from many relevant disciplines to the design and evaluation of tasks, jobs, products, environments, and systems. HFE takes into account physical, cognitive, sociotechnical, organizational, environmental and other relevant factors, as well as the complex interactions between the human and other humans, the environment, tools, products, equipment, and technology."[6] Many aspects of the ergonomic assessment are often outside the practice rights of physiotherapists. However, utilising the principles of integrative lifestyle medicine and whole person health can ensure a full and thorough ergonomic assessment with referrals to the proper clinician or healthcare provider. Next, read about the other components of ergonomics to illustrate how this field of study can fit into the practice of integrative lifestyle medicine.

Cognitive ergonomics assesses for potential cognitively challenging work conditions such as disruptions, interruptions and information overload which can impair a person's work performance and lead to a decreased well-being at work. Disruptions can include office background noise or coworker's speech, interruptions have negative consequences on productivity and job performance, information overload can also hinder job performance via multitasking or excessive input from communication apps or software.[10] Other factors taken into consideration during a cognitive ergonomic assessment include:

- Skills training

- Mental workload

- Decision-making processes

- Human-technology interaction

- Work stress load

- Social stress load

- Physical training

- Education

- Fatigue [9]

Organisational ergonomics, or macroergonomics, assesses the larger structures, policies and procedures of an organisation. It also takes the effects of technology on workers, processes, and the greater organisation into consideration. Examples of organisational ergonomics include:

- Teamwork

- Communication

- Quality management

- Crew resource management

- Introduction of new work paradigms

- Design of working times/duration

- Work design and flow

- Telework [9]

Sources of LBP for the Office Worker[edit | edit source]

Research supports that both prolonged sitting[11] and prolonged standing[12] can both result in LBP and musculoskeletal discomfort.[5] A 2020 study found that LBP was provoked by poor work station setup and design, poor lighting causing eye strain, and prolonged sitting of at least 4 hours/day in a group of Univsersity office workers in Thailand. The study also found that those with subjective reports of increased LBP had poor preventative behaviour, such as exercise, and a BMI ≤ 25.[13]

The COVID-19 global pandemic has changed the way many people work, especially those who work in an office setting. According to the US census bureau, more than a third of U.S. households reported a family member was working from home more frequently than before the pandemic.[14] Working from home may contribute to an increase in musculoskeletal discomfort and pain due to a lack of resources for proper ergonomic setup and assessment.[15] A study published in 2020 by Pekyavas found that in the transition to a home office environment, approximately 86% of the participants work at a desk set up and 65% and spent 3-8 hours/day working in that environment. Approximately half reported LBP as their most painful musculoskeletal complaint, followed by shoulder pain (44.8%), and knee pain (35.6%).[16]

These two short videos provide information on the effects prolonged sitting has on the body.

Prevention of LBP for the Office Worker[edit | edit source]

Clinical choices that can help an office worker manage and/or prevent LBP:

- What is the intention of the office break? Is the break needed for physical and/or mental needs?

- Physical: the worker may need to move, stretch, or change positions.

- Mental: the worker may need to step away from the task at hand or change tasks altogether.

- What should the worker do during the break? Rest in place, stand, sit, bend, stretch, move around?

- How long should an office microbreak last? 20 seconds to 120 minutes depending on the work and the need of the worker.

- How often should the microbreak occur? 20-120 minutes.

- What impact does other formal or scheduled breaks have on LBP? Examples: meal breaks

- What impact does chronic overwork over the year without taking a vacation break have on LBP and overall health?

List source the lecture

Practical Strategies for the Office Worker[edit | edit source]

MAKE TABLES FROM PPT

ADD VIDEO OF STRETCHES

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bontrup, C., Taylor, W.R., Fliesser, M., Visscher, R., Green, T., Wippert, P.M. and Zemp, R., 2019. Low back pain and its relationship with sitting behaviour among sedentary office workers. Applied Ergonomics, 81, p.102894.

- ↑ Vos, T., Allen, C., Arora, M., Barber, R.M., Bhutta, Z.A., Brown, A., Carter, A., Casey, D.C., Charlson, F.J., Chen, A.Z. and Coggeshall, M., 2016. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 388(10053), pp.1545-1602.

- ↑ Buruck G, Tomaschek A, Wendsche J, Ochsmann E, Dörfel D. Psychosocial areas of worklife and chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):480.

- ↑ Venes D. Tabers’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary, 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Altug, Z, LifeStyle Medicine and Office Ergonomic Strategies for Managing Low Back Pain. Integrative Lifestyle Medicine for Managing Low Back Pain. Physioplus. December 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 International Ergonomics Association. What is Ergonomics? Available from: https://iea.cc/what-is-ergonomics/#top (accessed 18/12/2021).

- ↑ Bridger R. Introduction to ergonomics. Crc Press; 2008 Jun 26.

- ↑ Youtube. Ergonomics self assessment. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aq1D5Bp3ANo (accessed 18/12/2021).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 U.S. Fire Administration. Emergency Services Ergonomics and Wellness. Available from: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/operations/ergonomics/ch1-ergonomics-human-factors-defined.html (accessed 19/12/2021).

- ↑ Kalakoski V, Selinheimo S, Valtonen T, Turunen J, Käpykangas S, Ylisassi H, Toivio P, Järnefelt H, Hannonen H, Paajanen T. Effects of a cognitive ergonomics workplace intervention (CogErg) on the cognitive strain and well-being: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. A study protocol. BMC psychology. 2020 Dec;8(1):1-6.

- ↑ Baker R, Coenen P, Howie E, Williamson A, Straker L. The short term musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of prolonged sitting during office computer work. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018 Aug;15(8):1678.

- ↑ Coenen P, Parry S, Willenberg L, Shi JW, Romero L, Blackwood DM, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Straker LM. Associations of prolonged standing with musculoskeletal symptoms—A systematic review of laboratory studies. Gait & posture. 2017 Oct 1;58:310-8.

- ↑ Hong S, Shin D. Relationship between pain intensity, disability, exercise time and computer usage time and depression in office workers with non-specific chronic low back pain. Medical hypotheses. 2020 Apr 1;137:109562.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. Working from home during the pandemic. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/working-from-home-during-the-pandemic.html (accessed 19/12/2021).

- ↑ Salajar R, Yulianto A. Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment of Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E) While Working from Home. American Journal of Engineering Research. 2021;10(2):140-144.

- ↑ PEKYAVAŞ NÖ, PEKYAVAS E. Investigation of The Pain and Disability Situation of The Individuals Working" Home-Office" At Home At The Covid-19 Isolation Process. International Journal of Disabilities Sports and Health Sciences. 2020;3(2):100-4.

- ↑ Youtube. Pain from Sitting Too Long? The Anatomy behind Prolonged sitting. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kU2tNCYTsg (accessed 19/12/2021).

- ↑ Youtube. TED ED Why sitting is bad for you. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUEl8KrMz14 (accessed 19/12/2021).