Introduction to the Facial Nerve: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Intracranial Course of the Facial Nerve == | == Intracranial Course of the Facial Nerve == | ||

The facial nerve exits the pons as two seperate roots, a motor root known as the facial nerve proper and a combined sensory and autonomic root known as the intermediate nerve (Waxmann 2020, Neuroanat), and pass through the cerebellopontine angle before it enters the internal auditory meatus/canal of the temporal bone (Takezawa 2017). At the internal auditory meatus the facial nerve lies in close proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve (also known as the auditory/acoustic/8th cranial nerve) with the nervus intermedius interposed (Takezawa 2017). Its close proximity to the auditory nerve (8th cranial nerve) at this point can potentially expose the facial nerve to damage. Benign, slow growing tumours, known as acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas), occasionally grow on the auditory nerve, necessitating surgical removal (Akinduro 2019). Due to its proximity to the auditory nerve, the facial nerve is vulnerable to damage during the surgical removal of the acoustic neuroma leading to facial palsy (Akinduro 2019). Very rarely the growing tumour could also put pressure on the facial nerve, causing facial palsy. | [[File:Facial and Vestibular Nerve Proximity.png|thumb|Proximity of Facial Nerve and Vestibulocochlear Nerve]] | ||

The facial nerve exits the pons as two seperate roots, a motor root known as the facial nerve proper and a combined sensory and autonomic root known as the intermediate nerve (Waxmann 2020, Neuroanat), and pass through the cerebellopontine angle before it enters the internal auditory meatus/canal of the temporal bone (Takezawa 2017). At the internal auditory meatus the facial nerve lies in close proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve (also known as the auditory/acoustic/8th cranial nerve) with the nervus intermedius interposed (Takezawa 2017). | |||

Its close proximity to the auditory nerve (8th cranial nerve) at this point can potentially expose the facial nerve to damage. Benign, slow growing tumours, known as acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas), occasionally grow on the auditory nerve, necessitating surgical removal (Akinduro 2019). Due to its proximity to the auditory nerve, the facial nerve is vulnerable to damage during the surgical removal of the acoustic neuroma leading to facial palsy (Akinduro 2019). Very rarely the growing tumour could also put pressure on the facial nerve, causing facial palsy. | |||

[[File:Acoustic neuroma.jpg|alt=|none|thumb|Acoustic Neuroma (Vestibular Schwannoma)]] | |||

== Intratemporal Course of the Facial Nerve == | == Intratemporal Course of the Facial Nerve == | ||

[[File:Schematic drawing of the facial nerve.png|thumb]] | |||

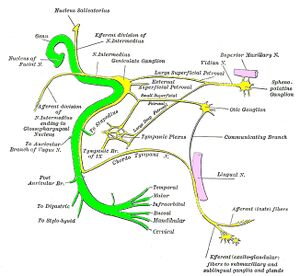

At the base of the meatus, the motor root (facial nerve proper) and nervus intermedius enters the facial canal (fallopian canal) where it merges to form the facial nerve. The facial nerve then forms the geniculate ganglion and 3 small nerve branches originate: (Takezawa 2017, Waxmann 2020) | At the base of the meatus, the motor root (facial nerve proper) and nervus intermedius enters the facial canal (fallopian canal) where it merges to form the facial nerve. The facial nerve then forms the geniculate ganglion and 3 small nerve branches originate: (Takezawa 2017, Waxmann 2020) | ||

| Line 17: | Line 22: | ||

* Chorda Tympani - contains special sensory fibres which supply taste sensation for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue as well as parasympathetic fibres to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands | * Chorda Tympani - contains special sensory fibres which supply taste sensation for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue as well as parasympathetic fibres to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands | ||

The facial nerve then exits the fallopian/facial canal, leaving the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen of the temporal bone. Following the close proximity of the nerve to the temporal bone, any temporal bone fractures could result in damage to the facial nerve. It is also useful to consider the bony fallopian/facial canal and its lengthy z-shaped course (3cm) . Bony canals are known as possible sites of entrapment for nerves especially in the presence of swelling when there is a lack of space for the nerve with concurrent loss of nerve conduction. | |||

The facial nerve then exits the fallopian/facial canal, leaving the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen of the temporal bone. Following the close proximity of the nerve to the temporal bone, any temporal bone fractures could result in damage to the facial nerve. It is also useful to consider the bony fallopian/facial canal and its lengthy z-shaped course (3cm) . Bony canals are known as possible sites of entrapment for nerves especially in the presence of swelling when there is a lack of space for the nerve with concurrent loss of nerve conduction. | [[File:Facial Nerve Bony Course.jpeg|none|thumb|Course of the Facial Nerve]] | ||

== Extracranial Course of the Facial Nerve == | == Extracranial Course of the Facial Nerve == | ||

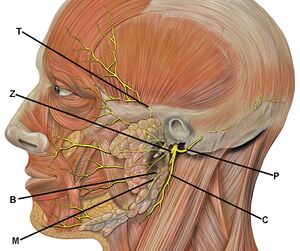

Outside of the skull, the facial nerve turns forwards and enters the posteriomedial surface of the parotid gland where it divides into a temporofacial division and a cervicofacial division containing the five terminal sets of branches that provide motor supply to the muscles of facial expression (Takezawa 2017). | Outside of the skull, the facial nerve turns forwards and enters the posteriomedial surface of the parotid gland where it divides into a temporofacial division and a cervicofacial division containing the five terminal sets of branches that provide motor supply to the muscles of facial expression (Takezawa 2017). | ||

[[File:Terminal branches of Facial nerve and supplies.jpg|frameless|600x600px]] | |||

High variability exists among these terminal branches due to varied peripheral branching and intercommunication between the different terminal branches (Raslan 2016). The intricate anatomical relationship of the facial nerve and the parotid gland is another site of vulnerability for facial palsy, especially following swelling of the parotid gland (as seen in mumps) or surgery to the parotid gland (parotidectomy) (Waxmann 2020, Prats-Golczer 2017), Guntinas-Lichius 2018). | High variability exists among these terminal branches due to varied peripheral branching and intercommunication between the different terminal branches (Raslan 2016). The intricate anatomical relationship of the facial nerve and the parotid gland is another site of vulnerability for facial palsy, especially following swelling of the parotid gland (as seen in mumps) or surgery to the parotid gland (parotidectomy) (Waxmann 2020, Prats-Golczer 2017), Guntinas-Lichius 2018). | ||

[[File:Facial Nerve Branches.jpeg|none|thumb|Terminal Branches of the Facial Nerve and its Proximity to the Parotid Gland ]] | |||

Discussing possible anatomic sites where the facial nerve can get damaged necessitates considering Bell’s palsy as the most common cause of facial paralysis. The etiology of Bell’s palsy is still unclear but reactivation of herpes simplex virus (cold sore virus) in the geniculate ganglion is suspected as the most likely cause (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). Post-mortem studies identified the underlying pathophysiology as vascular distention, inflammation and swelling with subsequent compression of the nerve in the narrow fallopian canal. Hypoperfusion (strangulation) and ischaemia of the facial nerve ensues, leading to damage of the axons and myelin sheaths with resultant nerve dysfunction (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is still mainly clinical and several other conditions need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of which Stroke (upper motor neuron lesion - patient is still able to wrinkle the forehead) and herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome) are the most pertinent (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). | Discussing possible anatomic sites where the facial nerve can get damaged necessitates considering Bell’s palsy as the most common cause of facial paralysis. The etiology of Bell’s palsy is still unclear but reactivation of herpes simplex virus (cold sore virus) in the geniculate ganglion is suspected as the most likely cause (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). Post-mortem studies identified the underlying pathophysiology as vascular distention, inflammation and swelling with subsequent compression of the nerve in the narrow fallopian canal. Hypoperfusion (strangulation) and ischaemia of the facial nerve ensues, leading to damage of the axons and myelin sheaths with resultant nerve dysfunction (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is still mainly clinical and several other conditions need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of which Stroke (upper motor neuron lesion - patient is still able to wrinkle the forehead) and herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome) are the most pertinent (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). | ||

| Line 39: | Line 47: | ||

A small number of patients may experience a delay in recovery after facial nerve injury, with subsequent development of synkinesis (Landing 2018, Heckmann 2019). Facial synkinesis is defined as “abnormal facial movements that occur during colitional or spontaneous movement, for example, voluntary movement of the mouth may result in closure of the eye” (Landing 2018). Even though the exact mechanism of synkinesis is still unknown, it is proposed to develop due to aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve during recovery resulting in “miswiring” of the nerve (Landing 2018). Synkinesis develops when more axons reach the muscles and therefore only becomes evident later in the recovery phase, around month 3 with parotid gland surgery, month 5-6 with Bell’s Palsy, and even later with acoustic neuroma surgery (6-9 months) due to the length of the axons. | A small number of patients may experience a delay in recovery after facial nerve injury, with subsequent development of synkinesis (Landing 2018, Heckmann 2019). Facial synkinesis is defined as “abnormal facial movements that occur during colitional or spontaneous movement, for example, voluntary movement of the mouth may result in closure of the eye” (Landing 2018). Even though the exact mechanism of synkinesis is still unknown, it is proposed to develop due to aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve during recovery resulting in “miswiring” of the nerve (Landing 2018). Synkinesis develops when more axons reach the muscles and therefore only becomes evident later in the recovery phase, around month 3 with parotid gland surgery, month 5-6 with Bell’s Palsy, and even later with acoustic neuroma surgery (6-9 months) due to the length of the axons. | ||

[[File:Facial nerve course.JPG|none|thumb|Facial Nerve with all its Branches]] | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

Revision as of 16:56, 25 May 2021

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Knowledge of the facial nerve, its course, function and vulnerabilities, is essential for the optimal management of any facial palsy. The facial nerve is one of the most important and continuously used nerves in the body, connecting at least 21 muscles with the brain,providing motor innervation to the muscles of facial expression which are also involved in mastication, speech and the expression of our emotions (Takezawa 201, Kehrer 2019). The anatomy of the facial nerve is highly complex and often described based on its relationship to the cranium or the temporal bone as intracranial, intratemporal and extracranial (Takezawa 2017, Myckatyn 2004, Kehrer 2019). Exploring the course of the facial nerve also highlights its possible vulnerabilities which could in turn result in the development of facial palsy. A very simplified explanation of the course of the facial nerve will be discussed in the next section to enhance the understanding of its potential sites of injury, and the impact thereof.

Intracranial Course of the Facial Nerve[edit | edit source]

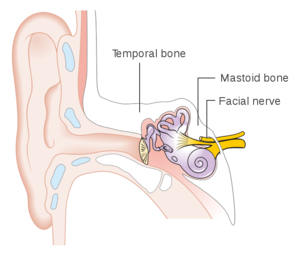

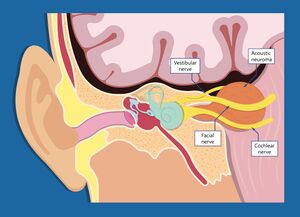

The facial nerve exits the pons as two seperate roots, a motor root known as the facial nerve proper and a combined sensory and autonomic root known as the intermediate nerve (Waxmann 2020, Neuroanat), and pass through the cerebellopontine angle before it enters the internal auditory meatus/canal of the temporal bone (Takezawa 2017). At the internal auditory meatus the facial nerve lies in close proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve (also known as the auditory/acoustic/8th cranial nerve) with the nervus intermedius interposed (Takezawa 2017).

Its close proximity to the auditory nerve (8th cranial nerve) at this point can potentially expose the facial nerve to damage. Benign, slow growing tumours, known as acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas), occasionally grow on the auditory nerve, necessitating surgical removal (Akinduro 2019). Due to its proximity to the auditory nerve, the facial nerve is vulnerable to damage during the surgical removal of the acoustic neuroma leading to facial palsy (Akinduro 2019). Very rarely the growing tumour could also put pressure on the facial nerve, causing facial palsy.

Intratemporal Course of the Facial Nerve[edit | edit source]

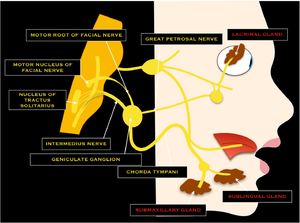

At the base of the meatus, the motor root (facial nerve proper) and nervus intermedius enters the facial canal (fallopian canal) where it merges to form the facial nerve. The facial nerve then forms the geniculate ganglion and 3 small nerve branches originate: (Takezawa 2017, Waxmann 2020)

- Greater Petrosal Nerve - this provides parasympathetic fibres to lacrimal glands of the eye and mucus membrane of the nasal cavity and palate

- Nerve branch to the Stapedius muscle in the middle ear which reflexively stabilises the tympanic membrane during sudden loud sounds

- Chorda Tympani - contains special sensory fibres which supply taste sensation for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue as well as parasympathetic fibres to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands

The facial nerve then exits the fallopian/facial canal, leaving the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen of the temporal bone. Following the close proximity of the nerve to the temporal bone, any temporal bone fractures could result in damage to the facial nerve. It is also useful to consider the bony fallopian/facial canal and its lengthy z-shaped course (3cm) . Bony canals are known as possible sites of entrapment for nerves especially in the presence of swelling when there is a lack of space for the nerve with concurrent loss of nerve conduction.

Extracranial Course of the Facial Nerve[edit | edit source]

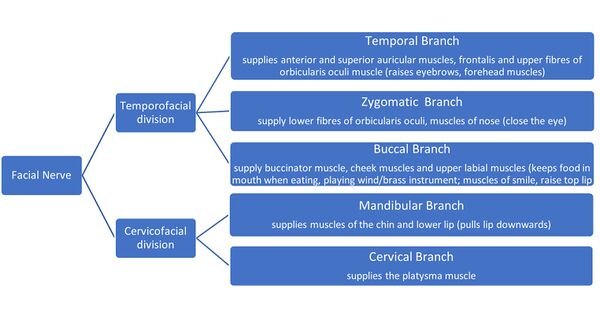

Outside of the skull, the facial nerve turns forwards and enters the posteriomedial surface of the parotid gland where it divides into a temporofacial division and a cervicofacial division containing the five terminal sets of branches that provide motor supply to the muscles of facial expression (Takezawa 2017).

High variability exists among these terminal branches due to varied peripheral branching and intercommunication between the different terminal branches (Raslan 2016). The intricate anatomical relationship of the facial nerve and the parotid gland is another site of vulnerability for facial palsy, especially following swelling of the parotid gland (as seen in mumps) or surgery to the parotid gland (parotidectomy) (Waxmann 2020, Prats-Golczer 2017), Guntinas-Lichius 2018).

Discussing possible anatomic sites where the facial nerve can get damaged necessitates considering Bell’s palsy as the most common cause of facial paralysis. The etiology of Bell’s palsy is still unclear but reactivation of herpes simplex virus (cold sore virus) in the geniculate ganglion is suspected as the most likely cause (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). Post-mortem studies identified the underlying pathophysiology as vascular distention, inflammation and swelling with subsequent compression of the nerve in the narrow fallopian canal. Hypoperfusion (strangulation) and ischaemia of the facial nerve ensues, leading to damage of the axons and myelin sheaths with resultant nerve dysfunction (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). The diagnosis of Bell’s palsy is still mainly clinical and several other conditions need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of which Stroke (upper motor neuron lesion - patient is still able to wrinkle the forehead) and herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome) are the most pertinent (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019).

Recovery after Facial Nerve Damage[edit | edit source]

Facial nerve injury is followed by an initial period of flaccid paralysis, whereafter many patients regain movement (Landing 2018). Recovery of the facial nerve is dependent on the extent of injury it acquired and the distance it needs to regrow. The anatomical sites where the nerve damage occurs also have a profound impact on the timescale of regrowth of the damaged nerve fibres. The further the degenerated axons have to regrow, the longer it will take them to reach their target muscles, considering axon regrowth occurs at a rate of 1mm/day (1cm/month). Expectations for recovery should therefore be set keeping the distance of required regrowth in mind, whether shorter distances such as from the parotid gland (3-4 months), or shorter terminal branches of the facial nerve (zygomatic to the eye or buccal to the cheek) (5-7 months) from injury following Bell’s Palsy or Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (Herpes Zoster virus, similar site of injury and timescale) or longer axons from the acoustic meatus following acoustic neuroma surgery or the longer nerve branches such as the temporal branch to the forehead or the mandibular branch to the chin.

It is also useful to keep the three degrees of nerve damage in mind as it also has a direct impact on the recovery timeframe for the nerve:

- Neuropraxia - temporary loss of function, no permanent damage, movements back to normal within 6-8 weeks

- Axonotmesis - Outer sheath is intact but the axon is damaged resulting in degeneration of the nerve. Regeneration/regrowth of the nerve is known to occur at a rate of 1mm/day (1cm/month)

- Neurotmesis - Complete severance of the nerve necessitating surgical repair.

The immediate treatment for Bell’s Palsy is therefore mostly aimed at reducing the swelling of the nerve in order to prevent axonal damage and incorporates 10 days of steroids, started within 72 hours of onset of the palsy (Somasundara 2017, Heckmann 2019). Around 71% of patients with Bell’s Palsy are expected to recover normally, leaving around 30% who will suffer axonotmesis damage and delayed return of muscle functioning (5-6 months) (Somasundara 2017). Initially these patients will be able to close their eyes and start moving their mouths in order to smile, but not yet raise their eyebrows as the temporal branch of the nerve is much longer than that of the buccal or zygomatic branches, and hence takes longer to regrow.

A small number of patients may experience a delay in recovery after facial nerve injury, with subsequent development of synkinesis (Landing 2018, Heckmann 2019). Facial synkinesis is defined as “abnormal facial movements that occur during colitional or spontaneous movement, for example, voluntary movement of the mouth may result in closure of the eye” (Landing 2018). Even though the exact mechanism of synkinesis is still unknown, it is proposed to develop due to aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve during recovery resulting in “miswiring” of the nerve (Landing 2018). Synkinesis develops when more axons reach the muscles and therefore only becomes evident later in the recovery phase, around month 3 with parotid gland surgery, month 5-6 with Bell’s Palsy, and even later with acoustic neuroma surgery (6-9 months) due to the length of the axons.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x