Introduction to Frailty

Introduction to Frailty[edit | edit source]

Frailty is associated with an increased risk of falls, harm events, institutionalisation, care needs and disability/death.[1] It affects quality of life and is becoming more common in our ageing populations.[1] While it is generally accepted that frailty exists, it remains difficult to define and measure as it manifests differently in each individual. However, a working definition of frailty is as follows: it is a distinct clinical entity from ageing, but it is related to the ageing process. It consists of multi-system dysregulation leading to a loss of physiological reserve. This loss of reserve means that the individual living with frailty is in a state of increased vulnerability to stressors meaning they are more likely to suffer adverse effects from treatments, diseases or infections. Morley et al (2013) provide the following definition:

“Frailty is a clinical state in which there is an increase in an individual’s vulnerability for developing increased dependency and/or mortality when exposed to a stressor.”[2]

This is a fairly complex definition, but it can be broken down into two key concepts:[1]

- It is a distinct process separate from aging, but related to the aging process. Thus, while older people tend to be more frailty, you are not frail just because you are old. Frailty depends on your physiological state and how adept you are at dealing with stressors, rather than just based on your age.

- Frailty involves multiple systems rather than just a single body system. Frail individuals will usually have a number of co-morbidities (eg cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and neurological).[1]

When clinicians come across the concept of frailty for the first time, it may initially seem easy to understand - we all have a sense of what a "frail" individual looks like. However, if we delve a little deeper, questions start to arise such as how do we differentiate between being frail and not frail? Or how can we record frailty when it manifests differently between individuals? To answer these questions we need to understand the pathophysiology of frailty and the theories that underpin this concept. There are two main theories of frailty: Fried's Phenotpye Model and Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model. It is important to understand that these are not competing models. They should be considered as complimentary as both have been validated. They have also been used as the basis for the development of different assessment tools and treatment indicators. You may want to use each model in different settings and for different patient groups. For example Fried's model is particularly good for assessing someone who is pre-frail and Rockwoods is better at incorporating cognitive disorders within someones frailty.

Fried's Phenotype Model[edit | edit source]

As a physiotherapist you may find this model more intuitive as you can use familiar outcome measures within each of the 5 sub categories. Each subcategory will give you a 0 or 1 score (0 being no and 1 being yes).

Fried’s framework outlines five criteria related to labelling a person as frail[3].

These include:

- Physical Inactivity - measured using the usual outcome measures you would expect

- Low muscle strength - can be measured in grip strength (<21kgf in men and <14 kgf in women however this is dependent on ethnicity)

- Slow gait speed - less than 0.8 m/s with or without a walking aid

- Exhaustion/ fatigue - this is self-reported

- Weight loss - loss of 10lbs or more in 1 year

0-1 = not frail 1-2 = pre-frail 3+ = frail (mild, moderate and severe)

Clearly these methods of measuring frailty in high levels of accuracy is flawed because someone who is not frail might have low grip strength due to a prior injury or condition and the same can be said for each criteria. This is why remembering that frailty is a multi-system dysregulation is essential. If you can clearly rule out something because of a mono-articular or single system problem then this must be considered. This is the reason the estimated prevalence of people living with frailty in different countries and within sub-sets of population can vary drastically [4].

This framework focusses solely on the physical attributes of frailty therefore there is an argument for saying this model is incomplete as it does not address cognitive aspects or chronic conditions which are associated with frailty [5].

Rockwood's Accumulation of Deficits Model[edit | edit source]

The Accumulation of Deficits approach considers the number of conditions present in the individual and gives the person a score of 0 to 1 known as the Frailty Index. The score is calculated through the (total number of impairments in the individual)/ (the total number of impairments examined). Impairment can be any sort of defecit from symptoms, signs, diseases or disabilities. This model dichotomizes each variable, you either have the defecit or you do not. The higher your overall score towards 1.0, the more frail you are considered5. Think of it as a descriptor of overall burden on a persons ability to cope. The model has high predictive ability for mortality in both men and women[6].

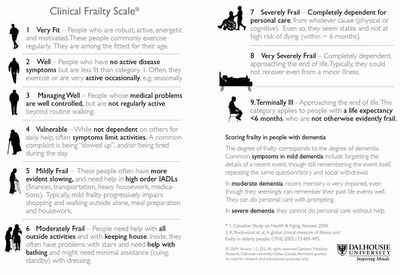

Clearly it is difficult to use this model in a quick glance or when meeting someone for first time. It requires time to accurately assess and understand the defecits an individual has therefore this is a useful model for primary care (GPs or Geriatricians) and where accurate detailed records of patients are kept. To make this model easier to use there are a number of developments. One being the electronic frailty index (eFI) which uses computer records to add up and accumulate the records giving a score quickly which is easily accessible. The other is the clinical frailty scale which is a really straightforward and accessible for clinicians of any speciality to use. It looks simpe, it is simple yet it is incredibly accurate at measuring a persons frailty score. As you can see the score uses a simple 1 to 9 scale with the pictures and words indicating the physcial abilities expected by people living with each level of frailty.

Particular attention should be payed to those who score 5 or more as this is the marker for requring a comprehensive geriatric assessment and often referral to geriatric or frailty specialists, A 2017 Cochrane review found that older people are more likely to be alive and in their own homes at follow-up if they received CGA on admission to hospital[7].

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

Both theoretical frameworks can be referenced and are valid in the literature. Fried’s criteria focusses solely on the physical aspects of frailty whereas Rockwood considers other deficits and chronic conditions.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Buxton S. An Introduction to Frailty course. Physioplus. 2020.

- ↑ Morley JE, Vellas B, Abellan van Kan G, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabel R et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013. 14(6): 392-7.

- ↑ Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol. 2001. 56A(3): 146-56.

- ↑ Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J, Wallace LMK, Brothers TD, Rockwood K. Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. Ageing Res Rev. 2015. 21: 78-94.

- ↑ Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, Ferrucci L, Chanves P, Varadhan R, Guralnik JM, Leng SX, Semba RD, et al. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol. 2009. 64(10): 1049-57.

- ↑ Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood MD. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010. 58: 681-7.

- ↑ Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, Conroy SP, Kircher T, Somme D, Saltvedt I, Wald H. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017(9). Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/CD006211/EPOC_comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-older-adults-admitted-hospital (last accessed 4.5.2019)