Human Trafficking Definitions and Legal Considerations: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

'''Human smuggling''' is voluntary. It is the exchange of fees or services to gain transportation or fraudulent documentation to illegally cross a border into a foreign country.<ref>US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Human Trafficking vs Human Smuggling. Available from: https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/CSReport-13-1.pdf (accessed 23/April/2023).</ref><ref name=":1" /> Human smuggling does not involve coercion, most people seeking out these services are fleeing violence or poverty.<ref name=":1" /> | '''Human smuggling''' is voluntary. It is the exchange of fees or services to gain transportation or fraudulent documentation to illegally cross a border into a foreign country.<ref>US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Human Trafficking vs Human Smuggling. Available from: https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/CSReport-13-1.pdf (accessed 23/April/2023).</ref><ref name=":1" /> Human smuggling does not involve coercion, most people seeking out these services are fleeing violence or poverty.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|A_Oe24le2mY|500}}<ref>YouTube. Human Trafficking vs Smuggling. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_Oe24le2mY [last accessed 14 June 2023]</ref> | |||

=== Consensual Commercial Sex versus Sex Trafficking === | === Consensual Commercial Sex versus Sex Trafficking === | ||

Revision as of 18:29, 14 June 2023

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (14/06/2023)

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Tarina van der Stockt, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Trigger warning. This page contains information about Human Trafficking, including physical abuse, sexual assault and abuse. There are links to videos which include survivor's first hand accounts of their experiences. All videos on this page are optional for course completion. Please view with caution.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

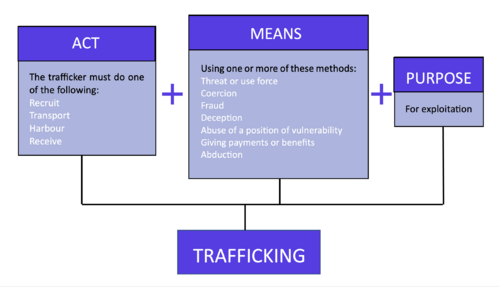

"Human Trafficking is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit. Men, women and children of all ages and from all backgrounds can become victims of this crime, which occurs in every region of the world." -United Nations, Office of Drugs and Crime[1]

The United States Department of State describes "trafficking in persons" "human trafficking" and "modern slavery" as interchangeable terms.[2]

Human trafficking is a global issue. It effects all races, genders, ages, and socio-economic groups. Recently, researchers, policy makers, and survivors of human trafficking are pushing to change the perception of human trafficking from a purely law enforcement issue to a public health issue.[3]

These crimes are widespread, and occur in every segment of society. However, human trafficking is often hard to identify and remains hidden from view. Gallo et al have suggested that regular screening and monitoring for trafficked persons at locations they are likely to visit could improve the possibility of identifying and assisting more trafficked people.[3] An estimated 22-88% of trafficked persons will come into contact with a healthcare professional during their exploitation.[4] Due to the nature of rehabilitation medicine assessment, documentation, and surveillance, healthcare professionals are well-suited to identify and assist trafficked persons.[3]

This article will provide an overview of key definitions and concepts, the different types and dynamics of human trafficking. It will also discuss how healthcare providers can identify, assess, and addict victims of human trafficking.

Concepts and Definitions[edit | edit source]

United States Federal Law[edit | edit source]

Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA), as amended (22 U.S.C. §7102).

Signed into law on October 28, 2020 by President Clinton, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) was created to “ensure just and effective punishment of traffickers, and to protect their victims.” The 2000 Act had three main components, commonly referred to as the three P's.

1. Protection: The TVPA increased the U.S. Government’s efforts to protect trafficked foreign national victims including, but not limited to:

- Providing assistance to victims of trafficking, many of whom were previously ineligible for government assistance

- Establishing non-immigrant status for victims of trafficking if they cooperated in the investigation and prosecution of traffickers

2. Prosecution: The TVPA authorized the U.S. Government to strengthen efforts to prosecute traffickers including, but not limited to:

- Creating a series of new crimes on trafficking, forced labor, and document servitude that supplemented existing limited crimes related to modern slavery and involuntary servitude

- Recognizing that modern slavery takes place in the context of force, fraud, or coercion and is based on new clear definitions for both trafficking into commercial sexual exploitation and labor exploitation

3. Prevention: The TVPA allowed for increased prevention measures including, but not limited to:

- Authorizing the U.S. Government to assist foreign countries with their efforts to combat trafficking, as well as address trafficking within the United States, including through research and awareness-raising

- Providing foreign countries with assistance in drafting laws to prosecute trafficking, creating programs for trafficking victims, and assistance with implementing effective means of investigation

In 2009, then Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton identified a fourth P, “Partnership,” to serve as a “pathway to progress in the effort against modern-day slavery.” [5]

Below is a list of definitions and concepts within the context of human trafficking. Please refer to this list as needed throughout the Rehabilitation's Role in Human Trafficking Awareness course.

- Coercion is a means of control. It is the act of persuading another person into action by means of threats or force. According to the TVPA (22 U.S.C. §7102), coercion "may be understood as threats of serious harm to or physical restraint against any person; any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe that failure to perform an act would result in serious harm to or physical restraint against any person; or the abuse or threatened abuse of the legal process."[6]

- Commercial Sex Act, according to the TVPA (22 U.S.C. §7102) is "any sex act on account of which anything of value is given to or received by any person."[6]

- Debt Bondage (also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage), according to the TVPA (22 U.S.C. §7102), is "the status or condition of a debtor arising from a pledge by the debtor of his or her personal services or of those of a person under his or her control as a security for debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied toward the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined."[6]

- Force, in the context of human trafficking, is a means of control over victims. The use of monitoring and/or confinement is often used during the early stages of victimization to erode the victim's resistance. Physical forms of force used in human trafficking can include: physical restraint, and physical and sexual assault. This is related to harbouring of a victim which involves isolation, confinement, and monitoring.[7]

- Fraud, according to the TVPA (22 U.S.C. §7102), "consists of some deceitful practice or willful device, resorted to with intent to deprive another of his right, or in some manner to do him an injury. In the context of human trafficking, fraud often involves false promises of jobs or other opportunities." [6]

- Human Smuggling is the exchange of fees or services to gain transportation or fraudulent documentation to illegally cross a border into a foreign country.[8]

- Involuntary Servitude (also known as involuntary slavery), according to the TVPA (22 U.S.C. §7102), "includes a condition of servitude induced by means of (A) any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe that, if the person did not enter into or continue in such condition, that person or another person would suffer serious harm or physical restraint; or (B) the abuse or threatened abuse of the legal process."[6]

- Labour trafficking (also known as forced labour), according to the TVPA, is defined as, “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.”[9]

- Obtaining, in the context of human trafficking, is the forced taking or exchange of something to gain control over another person.[7]

- Patronizing, in the context of sex trafficking, is receiving a sexual act or sexually explicit performance.[7]

- Recruiting is the proactive targeting of vulnerable persons and the grooming of wanted behaviours by means of fraud and coercion by human traffickers.[7]

- Sex trafficking, according to the TVPA, is defined as, “a commercial sex act that is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age.”[9]

- Slavery, in the context of human trafficking, is when a controlled person is forced to provide labour and/or services against their will.[7]

- Soliciting, in the context of sex trafficking, involves the offering a sexual act or sexually explicit performance.[7]

- Transporting includes the movement and arrangement of travel for persons being trafficked.[7]

Human Trafficking versus Human Smuggling[edit | edit source]

| Human Trafficking | Human Smuggling | |

|---|---|---|

| Consent |

|

|

| Victim of the crime | committed against an individual | committed against a country |

| Domestic or Transitional |

|

Smuggling is transnational by definition |

Human trafficking is involuntary. The victims are trafficked by force, fraud, and/or coercion to provide labour or services against their will. Human trafficking victims do not have to be moved, relocated, or transported in any way.[7][8] It can occur in the victim's own town or home. In the United States, any person under the age of 18 who is a victim of sex for profit is automatically considered a trafficking victim.[8]

Human smuggling is voluntary. It is the exchange of fees or services to gain transportation or fraudulent documentation to illegally cross a border into a foreign country.[10][8] Human smuggling does not involve coercion, most people seeking out these services are fleeing violence or poverty.[8]

Consensual Commercial Sex versus Sex Trafficking[edit | edit source]

| Consensual Commercial Sex | Sex Trafficking | |

|---|---|---|

| Consent |

|

|

| Person involved | Sex workers are consenting adults | Victims of sex trafficking can include men, women, and children |

| Payment for Services | Sex workers earn and keep income | All income or services go to the trafficker, not the victim |

"Sex work is consensual. Human trafficking is not. When you conflate the two, and you label all sex workers as victims of human trafficking, it totally takes away from the folks who are being trafficked" [13]

-Julia Baumann

founder and coordinator of Safe Space, a drop-in centre for sex workers in London

Consensual Commercial Sex (also known as sex work) is when a person willingly takes part in the sale of a consensual sexual act or conduct.[12]

Sex Trafficking (also known as Sexual Exploitation) is the sale of nonconsensual sexual acts or conduct through force or coercion.[12]. Victims of sex trafficking include all races, genders, ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and nationalities.

Human Trafficking[edit | edit source]

Introduction/Statistics

More than 175 nations have ratified or acceded to the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (the UN TIP Protocol), which defines trafficking in persons and contains obligations to prevent and combat the crime.[2]

- Trafficking does not require crossing internations or state borders

- Limitations of data on human trafficking

The extent of human trafficking is difficult to establish and the tracking of trafficking is challenging for many complex reasons: (1) navigating legal definitions, (2) trafficker movement restrictions and isolation of victims, (3) the fear and stigma of victim self-reporting, and (4) the lack of frontline professionals trained in identification and monitoring of human trafficking.[3]

Types of Human Trafficking[edit | edit source]

The US State Department recognizes two types of human trafficking, and classifies them as federal crimes:[2]

- Labour trafficking (also known as forced labour) involves the use of force, fraud, and/or coercion to obtain labour from the trafficked person. Labour trafficking can occur within any industry or sector: agriculture and meat farming, factory work, hospitality industry such as restaurants, hotels, or massage parlors; retail, mines, private home, or drug trafficking operations.

Two widespread forms of labour trafficking include:[2]- Domestic servitude involves a victim performing forced labour in a private residence.[2]

- Forced child labour involves children being forced or coerced to work. Unfortunately forms of slavery including the sale of children, and debt bondage of children continue to exist across the world. Forced child labour is different from children who are able and choose to legally seek employment and work.

- Some indicators of forced child labour include (1) when the child appears to be in the custody of a non-family member and their work benefits that person, (2) withholding food, rest, or schooling to a child who is working.[2]

- Sex trafficking involves the use of force, fraud, and/or coercion to perform a commercial sexual act or conduct. The victim can suffer threats of serious physical or psychological harm, threats to friends or family, or debt bondage. Sex trafficking can occur in any location including physical locations and on the internet.[2] Examples of sexual exploitation can include: prostitution, escort agencies, phone sex lines, stripping on a web cam or internet chat rooms, and pornography.[15] ,

- Child sex trafficking involves sex trafficking with a person under the age of 18 years. The use of force, fraud, or coercion is irrelevant, children engaging in commercial sex is illegal in most countries around the world.[2]

The United Nations, private and not-for-profit organizations such as Stop the Traffick acknowledge other types of human trafficking to include:

- Forced marriage[2][16] occurs when a person is forced into marriage under threats of force, fraud or through coercion. Situations where forced marriage may occur include: as access into a country or access to benefits.[15]

- Forced criminal activity[2] [16]involves a person carrying out a criminal activity under threats of force, fraud or through coercion. Forced criminality can include: drug distribution, cannabis cultivation, begging, pickpocketing or bag snatching, ATM theft, or the selling of counterfeit goods.[15]

- Child soldiers[2] involves a child serving as a soldier or to commit a crime to the benefit of the trafficker under threats of force, fraud or through coercion.[16]

- Organ harvesting[2] [16]and trafficking involves the removal of an organ or body part to sell on the blackmarket. The victim can be cheated out of an agreeabled upon price for the organ, have an organ removed without their knowledge during treatment for another medical condition, or kidnapped and have an organ removed without their consent.[15]

Dynamics of Human Trafficking[edit | edit source]

Trafficker[edit | edit source]

People who deal in human trafficking do so for monetary and financial gain. These crimes go undercounted and unrecognized because they are often difficult to detect.

Trafficker Profiles[edit | edit source]

CHANGE THIS QUOTE?

"In 2020, 42% of trafficking victims were brought into trafficking by a member of their own families and 39% were recruited via an intimate partner or a marriage proposition."[17] -The Polaris Project

Both US and international law state that human traffickers can be classified as corporations or other legal entities, or private persons.[18]. According to an extensive review of federal human trafficking prosecution in the United States since TVPA was enacted in 2000 found that the vast majority of prosecuted human traffickers were private persons. The review found that in 2020, the average defendant was a 36yo man, with 81% of all human trafficking case defendants being male. When comparing sex and labour trafficking cases from 2020, men made up 82% of defendants in sex trafficking cases and women made 43% of defendants in labour trafficking cases. This data was found to track with global trends,[19] however there is no one human trafficker's profile type and they could come from any segment of the population. Human traffickers can be foreign nationals or local citizens, family members, spouses/partners, friends, acquaintances, or strangers. They can be individual actors or part of a larger organisation. They can be pimps, gang members, diplomats, or business owners.[20]

The review went on to say that traffickers often know and have a trusting relationship with their victim. Data on sex trafficking cases from 2020, approximately 43% of defendants previously knew their victims. Of these cases: 31% were social media contacts, 21% as a spouse or intimate partner, 13% as a human smuggler, and 10% as a friend or classmate. Data on labour trafficking cases found approximately 57% of defendants previously knew their victims.[19]

At what point a person transitions to a trafficker can be difficult to identify. The review points to the fact that the nature of the coercion used by the trafficker are highly personalised.[19]

Trafficker Recruitment Techniques[edit | edit source]

Human trafficking recruitment is often based on the deception of innocent, unsuspecting victim. Recruitment techniques commonly used by traffickers include:

- Threats or use of violence[21]

- Manipulation[19][21]

- Seduction and romance[19][21][22]

- Forced pregnancy[22]

- False employment promises[21][22]

- False promises about education or travel[22]

- Sale by family[22]

- Recruitment of formerly enslaved persons[22]

- Abuse of religious beliefs[19][22]

- Abduction[22] or kidnapping

In some cases, a former victim of human trafficking will become a trafficker themselves. This is most commonly the case of female victims of sex trafficking.[19]This speaks to the grooming and psychological manipulation victims of human trafficking suffer and endure.

The Trafficked Person[edit | edit source]

Trafficked persons can come from any segment of the population, however traffickers tend to prey upon people with the following vulnerabilities:

- Poverty/economic hardship[21][20]

- Limited English proficiency[20]

- Lack of lawful immigration status[20]

- lack of stable safe housing[20]

- Lack of a social safety net[21]

- Following a natural disaster, war or political instability[21]

- Limited economic and educational opportunities[20]

- Psychological or emotional vulnerability[21]

Trafficked persons are often tricked or mislead into trafficking by (1) false romantic intentions, (2) promises of good employment or pay, and (3) a stable life.[20]. They can be of any gender or age, and come from any educational, socio-economic, ethnicity or nationality, or religious background. However, women and girls are at a higher risk of being trafficked for sexual exploitation. Refugees are also often victimised due to dire living situations in refugee encampments. [22]

Red Flags and Health Impact of Human Trafficking[edit | edit source]

"Polyvictimization, also known as complex trauma, describes the experience of multiple victimizations of different types, such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, bullying, exposure to family violence, and more. This definition emphasizes different kinds of victimization, rather than just multiple episodes of the same kind of victimization, because it signals a generalized vulnerability. Research shows that the impact of polyvictimization is much more powerful than even multiple events of a single type of victimization." - National Children’s Advocacy Center[23]

Physical Health

- Reproductive/Sexual health: frequent treatment of sexually transmitted infections or injuries, multiple unwanted pregnancies[24], lack of sexual desire or oversexualised behaviours[23]

- Signs of physical abuse: fractures or burns[24][25], bruising[24]; signs of concussions, traumatic brain injuries or unexplained memory loss[24]

- Gastrointestinal problems[24]

- Malnutrition[24]

- Changes in sleep: sleeplessness, sleep disturbances, nightmares, and/or insomnia[23]

- Fatigue[23]

- Skin or respiratory problems caused by exposure to agricultural or other chemicals[24]

- Communicable and non-communicable diseases[24]

- Oral health issues, including broken teeth[24]

- Chronic pain[24]

- Tattoos or branding of ownership[24][25]

Emotional/Psychological Health

- Unable to concentrate or provide basic information including age, address or time[24]

- Substance abuse[24]

- Self-harm and suicidal ideation[23]

- Depression, anxiety[24], panic attacks[23]

- Fear of being alone, distrust and fear of strangers[23]

- Guilt, shame, and/or self-blame [23]

- Post-traumatic stress disorder[24]

- Eating Disorders[23]

- Suspicious behaviour: appears nervous or avoids eye contact;[24] seems overly fearful, submissive, tense, or paranoid[25]

- Has a lack of autonomy or independence. Person will defer to another before giving information[25], no control over identification documents[25]

- Cultural, linguistic barriers and isolation[23]

- Withholds information. The person can be unwilling to answer questions about their health, gives confusing or contradicting information[24]

Victims of human trafficking suffer physical, mental, emotional, and psychological injuries. They loose their independence and autonomy. Their quality of life is hugely and devastatingly effected. A study by Hossain et al interviewed more than 200 victims of sex trafficking and assessed for mental health and quality of life. They found 55% had high levels of depression symptoms, 48% had high levels of anxiety symptoms, and 77% were potentially suffering from PTSD.[26]

Please read here for a list of Red Flags of Labour Trafficking provided by the State of Texas, USA.

Please read here for a list of Red Flags of Sex Trafficking provided by the State of Texas, USA.

Interaction and Assessment of a Trafficked Person[edit | edit source]

Healthcare professionals can affect human trafficking with accurate identification of trafficked persons. Proper identification requires healthcare professionals be familiar with vulnerabilities and red flags of human trafficking that may be revealed during routine assessments, especially when taking a detailed social history. A small number of human trafficking screening tools are available for use in the clinic.[27] Unfortunately, there are only a handful of validated screening tools available for clinician use. Many of the tools would be of limited practical use in the health care environment because they (1) lack of evidence-based support, especially for the health care environment, (2) have long administration times which may be difficult to utilise in the fast-paced medical setting, (3) require the administrator to have expertise in human trafficking, and (4) only available and/or validated in the English language.[4] Please see the resource section at the end of this article for downloadable options.

Once a trafficked person has been identified, the healthcare professional should interact with them in the following ways:

Respect for autonomy.[28]

- Use the term "trafficked person" or "trafficking survivor" rather than "trafficking victim" to change the misconception that persons who have endured this form of trauma are "helpless victims."

- Treat trafficked persons as moral agents who have retained or can regain capacities for self-determination and decision making power.

- Trafficked persons deserve dignified respectful healthcare, which includes right enjoyed by all patients such as: privacy in their care, and use of a professional medical interpreter. This also includes explanation of the legal limitations of medical confidentiality due to the mandatory reporting requirements of human trafficking to the proper authorities.

Special Topic: Mandatory Reporting Laws to Address Human Trafficking[29]

In the United States, healthcare professionals are legally requires to make a report to law enforcement or child protection agencies when they have an interaction with a trafficked person. These laws include: (1) mandatory child abuse reporting laws, (2) domestic violence reporting laws, and (3) laws requiring reports of knife or gunshot wounds.

Benefits of these laws: Healthcare professionals are incentivised to report human trafficking under these laws, which should increase the overall awareness of human trafficking and improve education and assessment skills within the healthcare community. Triggering an appropriate investigation can result in protective measures for trafficked persons and prosecution of the traffickers. A growing number of states have created "safe harbor" laws where trafficked persons are not treated as criminals but rather survivors in need of trauma-informed care and supportive services.

Risks of these laws: While mandatory reporting laws can protect and benefit trafficked persons, they also invoke vulnerability risks of trafficked persons related to their mistrust of authorities and fear of their traffickers. These reporting requirements also override the confidentiality protections that normally apply in healthcare settings. This has the potential for trafficked person to loose trust in the healthcare system due to their fear reprisal by their traffickers, prosecution by law enforcement, or deportation.

To ensure the protection and safety of trafficked person, healthcare and law enforcement professionals must be properly trained in human trafficking and their roles as part of a multidisciplinary team. Trafficked persons must have access to trauma-informed care, and support systems must have the necessary resources to provide meaningful prevention and protection. With measures in place to ensure that the risks of mandatory reporting laws are limited, healthcare professionals can assume the role of mandatory reporters of human trafficking while meeting their ethical obligations.

Nonmaleficence and Beneficence.[28]

- All healthcare professionals have an obligation to first do no harm (nonmaleficence) and to act in the best interests (beneficence) for our patients. Examples of positive interactions between patients and healthcare providers include (1) the removal from harm, (2) prevention of harm, and (3) promotion of good.

- The principle of nonmaleficence cautions against pressuring for a disclosure that they are being trafficked, especially in the presence of the trafficker. Aggressive attempts can be psychologically harmful for the trafficked person, and canpotentially trigger intense stress, anxiety, fear, and retraumatising the individual,

- A trafficked person's decision over disclosing their situation and whether to accept clinical assistance are based on the individual person's firsthand experience and knowledge of the potential trafficker repercussions. For this reason, the patient's decisions must be respected to the extent possible when mandatory reporting laws do not apply.

Justice. [28]

- The unique circumstances surrounding the care of trafficked persons often challenge the concept of justice (the fair distribution of resources) by limiting trafficked persons’ ability to access appropriate and affordable health care outside of acute injuries and illnesses.

- Many healthcare professionals do not receive appropriate education and training to recognise the signs and symptoms of human trafficking. This is significant as it leaves healthcare professionals unable to comprehensively assess and respond to the complex and challenging healthcare needs of trafficked persons.

- Healthcare professionals must make treatment decisions for trafficked persons while considering the possibility of nonadherence and limited ability to follow through with long-term treatment plans, often for reasons outside of their control. Examples of pressing treatment needs for this population can include communicable diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illnesses. A healthcare professionals decision to not test or initiate interventions due to assumptions about medical adherence must be carefully weighed against potential trafficker repercussions. At times it may be necessary to make referrals to known and trusted organizations or other providers to find alternative options to manage the unique challenges and circumstances for trafficked persons.

- Interacting with a trafficked person

- provides samples of appropriate language to assist with identification.

- provides strategies to have private conversations with potential trafficked persons.

- Safety concerns

- measures to keep oneself and patients safe.

- describes the importance of appropriate documentation

Response and Follow Up[edit | edit source]

Healthcare providers can impact human trafficking using a multi-level approach, advocating for change from bedside care to society level.[27]. The use of an ecological framework will provide the most holistic and wide-reaching response to human trafficking. The levels of response within this framework include: (1) individual-level healthcare provider training, (2) health facility–level screening policies and response protocols, (3) community-level multidisciplinary resources and response teams, and (4) society-level awareness campaigns, funding allocation, and data collection.[4]

| Framework level | Examples of Interventions |

|---|---|

| Individual-level |

|

| Health facility–level |

|

| Community-level |

|

| Society-level |

|

Intervention and Response[edit | edit source]

Healthcare professionals can provide individualised interventions to trafficked persons to address human trafficking vulnerability factors and red flags within the safety of the health care setting. This can include:

- the initiation of established organisational protocols

- referral to trusted and vetted providers or outside organisations

- utilisation of trauma-informed and people-centred screening processes

- education on communicable diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illnesses within your scope of practice

Special Topic: Trauma-Informed Ethics of Care[28]

The trauma-informed approach to care is strongly recommended as a beneficial framework for caring for survivors of physical and psychological trauma, which includes persons who have experienced human trafficking. For these patients, effective care requires a sensitive, compassionate, measured approach with attention to health care practices to limit the triggering of fear, stress, shame and stigmatisation. Examples include: mindful sensitive wordage and proper verbal cues when requesting a patient disrobe for examination and assessment, and nonjudgement education on use of contraception.

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the trauma-informed approach:

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma

- Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma

- Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices

- Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization

Healthcare professionals also have a wider responsibility to their greater community. As specialised educators and advo+cates healthcare professionals can collaborate with community and society level stakeholders and lawmakers to help bring about change and support for trafficked persons. This can include:[27]

- increasing awareness of human trafficking through healthcare facility and community level education programmes

- advocating for local and national policies which promote community health and wellness

- combating social or cultural norms that contribute to human trafficking

- creating and maintain an evidence-based guide and training programme to prevent future human trafficking

Referrals[edit | edit source]

- describes the importance of survivor-centered, multidisciplinary referrals within the health care organization and with community partners.

- includes a discussion on the importance of building a trusted local network of resources

- includes a discussion of the implications of law enforcement involvement

- includes a discussion of mandated reporter obligations

Resources[edit | edit source]

Texas

Michigan

Resources

- provides information on how to contact your community, local, and/or state resources.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline number and text number along with any local hotlines.

https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/First-Aid-Kit/First_Aid_Kit_-_Booklet_eng.pdf

Screening Tools for Health Care Practitioners

source: https://www.hhs.texas.gov/services/safety/texas-human-trafficking-resource-center

Commercial Sexual Exploitation-Identification Tool (CSE-IT)

CSE-IT is a research-based screening tool that helps improve early identification of commercially sexually exploited youth. West Coast Children’s Clinic developed this tool, which is currently used in Texas and other states and across various sectors.

Learn more about CSE-IT on the Office of the Texas Governor Child Sex Trafficking Team website and on the West Coast Children's Center website.

Short Child Sex Trafficking Screen for the Health care Setting

Dr. Jordan Greenbaum with The Institute on Healthcare and Human Trafficking developed this validated screening tool for assessing teenagers seeking health care in the United States.

Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide

Administration for Children and Families designed this survivor-centered, trauma-informed and culturally appropriate screening tool and guide. It can help health care providers in various sectors assess adult patients or clients for signs of potential exploitation or risk of being exploited.

Learn more about the Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool and Guide on the U.S. Office on Trafficking In Persons website.

Trafficking Victim Identification Tool and Manual

Vera Institute for Justice developed this tool and manual, which are intended primarily for victim service agency staff and other social service providers who are screening potential adult and child trafficking victims. Law enforcement, health care and shelter workers will also find it helpful in improving trafficking victim identification, especially in conjunction with appropriate training or mentoring.

Learn more and download the tool on the Vera Institute for Justice website.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. Human Trafficking. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-Trafficking/Human-Trafficking.html (accessed 22/April/2023).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 US. Department of State. Understanding Human Trafficking. Available from: https://www.state.gov/what-is-trafficking-in-persons/ (accessed 22/April/2023).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Gallo M, Thinyane H, Teufel J. Community health centers and sentinel surveillance of human trafficking in the United States. Public Health Reports. 2022 Jul;137(1_suppl):23S-9S.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Munro-Kramer ML, Beck DC, Martin KE, Carr BA. Understanding health facility needs for human trafficking response in Michigan. Public Health Reports. 2022 Jul;137(1_suppl):102S-10S.

- ↑ Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking. Summary of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) and Reauthorizations FY 2017. Available from: https://endslaveryandtrafficking.org/summary-trafficking-victims-protection-act-tvpa-reauthorizations-fy-2017-2/ (accessed 14 June 2023).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Department of Defense. Key Terms & Definitions. Available from: https://ctip.defense.gov/Portals/12/1%202_Key_Terms_and_Definitions_FY%2021_Final_v2.pdf (accessed 14 June 2023).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 US Department of Health and Human Services. Fact Sheet: Human Trafficking. Available from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/otip/fact-sheet/resource/fshumantrafficking (accessed 22/April/2023).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 The Polaris Project. Trafficking vs. Smuggling: Understanding the Difference. Available from: https://polarisproject.org/blog/2021/05/trafficking-vs-smuggling-understanding-the-difference/ (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 US Government Information. H. R. 3244. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-106hr3244enr/pdf/BILLS-106hr3244enr.pdf (accessed 14 June 2023).

- ↑ US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Human Trafficking vs Human Smuggling. Available from: https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/CSReport-13-1.pdf (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ YouTube. Human Trafficking vs Smuggling. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_Oe24le2mY [last accessed 14 June 2023]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Stop the Traffick. Sex Trafficking vs Sex Work: Understanding The Difference. Available from: https://www.stopthetraffik.org/sex-trafficking-vs-sex-work-understanding-difference/ (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ CBC Radio-Canada. Don't mix up sex work and sex trafficking, advocates for workers say. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/london-ontario-safe-space-sex-work-not-human-trafficking-1.4984323 (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. Human Trafficking, the Crime. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/crime.html (accessed 4 May 2023).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Stop the Traffick. Types of Exploitation. Available from: https://www.stopthetraffik.org/what-is-human-trafficking/types-of-exploitation/ (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. The Crime. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/crime.html (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ The Polaris Project. Love and Trafficking. Available from: https://polarisproject.org/love-and-trafficking/ (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ Assembly UG. United Nations millennium declaration. United Nations General Assembly. 2000 Sep 8;156.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 Wheeler AC. Trafficker profile according to US federal prosecutions. Anti-trafficking review. 2022 Apr 19(18):185-9.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 US Department of Justice. What is Human Trafficking. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/humantrafficking/what-is-human-trafficking#:~:text=Although%20there%20is%20no%20defining,stable%2C%20safe%20housing%2C%20and%20limited (accessed 26/April/2023).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 Department of Homeland Security, Blue Campaign. What Is Human Trafficking?. Available from: https://www.dhs.gov/blue-campaign/what-human-trafficking (accessed 23/April.2023).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 High Speed Training. Methods of Human Trafficking and Recruitment. Available from: https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/methods-of-human-trafficking/ (accessed 23/April/2023).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 Office of Justice Programs. Mental Health Needs. Available from: https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/4-supporting-victims/44-comprehensive-victim-services/mental-health-needs/#:~:text=The%20types%20of%20physical%20and,narcotics)%2C%20and%20eating%20disorders. (accessed 28/April/2023).

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 24.12 24.13 24.14 24.15 24.16 Texas Health and Human Services. Texas Human Trafficking Resource Center. Available from: https://www.hhs.texas.gov/services/safety/texas-human-trafficking-resource-center (accessed 28/April/2023).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Attorney General of Texas. Red Flags for Sex Trafficking. Available from: https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/human-trafficking-section/signs-trafficking/red-flags-sex-trafficking (accessed 28/April/2023).

- ↑ Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Abas M, Light M, Watts C. The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. American journal of public health. 2010 Dec;100(12):2442-9.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, et al. Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: the role of health care professionals. Prev Med. 2018;114:164-167.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Caring for the trafficked patient: ethical challenges and recommendations for health care professionals. AMA journal of ethics. 2017 Jan 1;19(1):80-90.

- ↑ English A. Mandatory reporting of human trafficking: potential benefits and risks of harm. AMA journal of ethics. 2017 Jan 1;19(1):54-62.