Holistic Healthcare Interventions for Children

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, Tarina van der Stockt and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Holistic healthcare refers to examining the whole body, including the physical, mental, spiritual, emotion and social well-being of the individual rather than focusing on one element In holistic health all components are seen as intertwined. If one aspect is not functioning optimally, it can affect overall health. Empowered Parents[1] have described the five aspects of holistic development as follows:

- Physical – developing the body and senses optimally

- Intellectual – learning, developing mental processes, language and thinking

- Social – integrating with others and communicating well

- Emotional – healthy expression of feelings, building emotional intelligence

- Spiritual – developing morals, values and personality traits[1]

These five components develop simultaneously in children and not in isolation. A child does not develop physical skills separate from social-emotional skills. A delay in one aspect of development can impact another. A physical issue such as a hearing impairment could impact intellectual development. A child who is emotionally upset may have issues concentrating and learning in school. Therefore, practitioners working with children utilising a holistic approach gain a better insight into the underlying cause of the child’s problem.[1]

Stress[edit | edit source]

Stress is a good example of how an emotional component can have physical manifestations such as headache, muscle pain and weight gain. Stress is inherently a part of life for most organisms. The brain processes stress, alerts the body of danger via the “flight or fight” mechanism and encourages survival. Various stressors affect the body differently based on their duration and intensity. In addition, individuals perceive, assess and cope with stressors differently.[2] These variances in individuals can be a result of experiential factors, as well as genetics.[2] Responses to stress are kept in check by our body’s autonomic nervous system.[3]

Autonomic Nervous System[edit | edit source]

The autonomic nervous system maintains homeostasis by modulating involuntary physiologic processes including respiration, digestion, heart rate and blood pressure.[4] The autonomic nervous system is comprised of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.[3] The sympathetic nervous system, ”fight or flight” response induces increased movement and strength. This system is activated during stressful situations, exercise, and moments before waking up. Cell bodies of the sympathetic nervous system can be found from T1-L2. The parasympathetic nervous, “rest and digest” works in opposition to the sympathetic nervous system. Cell bodies of the parasympathetic system can be found in cranial nerves III, VII, IX, and X and S2-S4.[3] Aspects of the specific physiological activity of each system are described below.

Sympathetic Nervous System[edit | edit source]

- Increase in:

- Heart rate

- Blood flow to muscles

- Muscle contractility

- Sweat gland secretions

- Dilation of:

- Pupils

- Lungs

- Coronary arteries

- Decrease in:

- Gastrointestinal motility

- Urine output[3]

Parasympathetic Nervous System[edit | edit source]

- Decrease in:

- Heart rate

- Contractility of the cardiac muscle

- Constriction of:

- Pupils

- Lungs

- Increase in:

- Salivary glands

- Gut motility [3]

The body responds to stressors by activating the sympathetic nervous system and inhibiting the parasympathetic system. Short-term stress lasts for a period of minutes to hours, whereas chronic stress continues for several hours per day for weeks or months.[2] With chronic stress, our body becomes dysregulated and adverse side effects can occur. Children dealing with chronic stress may become anxious and depressed, which can lead to delays in other developmental foundations (physical, social, etc.)

Pillars of Health[edit | edit source]

Healthcare practitioners working with children utilising a holistic approach should assess the three pillars of health, sleep, diet and exercise. Evaluating these three pillars allows the practitioner to know if one factor is hindering the well-being of the child. Tracy Prowse[5] includes a fourth pillar in the pillars of health: stress management (see discussion of stress above). Teaching children good sleep hygiene, proper diet and the importance of exercise will promote good coping responses to everyday stressors within their life.[5]

Pillar 1: Sleep[edit | edit source]

Healthy sleep is crucial for cognitive functioning, mood and cardiovascular health.[6] Sleep consists of two distinct phases referred to as rapid-eye movement (REM) and non rapid-eye moment (NREM). See below for an understanding of the differences in REM and NREM sleep.[7]

REM[edit | edit source]

- Short periods

- Structured dreams

- Decrease in muscle tone

- Sympathetic activation

- Increase in:

- Heart rate

- Breathing

- Blood pressure

- Temperature[7]

- Increase in:

NREM[edit | edit source]

- Longer periods of time

- Non-structured and bizarre dreams

- Parasympathetic activation

- Decrease in:

- Blood pressure

- Heart rate

- Temperature[7]

- Decrease in:

- Parasympathetic activation

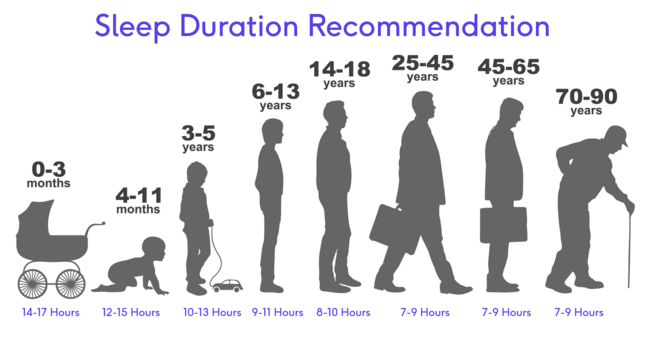

Sleep deprivation can have a profound impact on mental and physical health.[6] REM sleep is the time when the brain processes emotions. Sleep deprivation during this period can lead to heightened emotions and increased anxiety. During NREM, our brains are focused on memory filling, creativity and learning.[7] Sleep interruptions during this part of the sleep cycle can affect any of these facets. Studies show that 74% of high school student and 34% of children are failing to get a sufficient amount of sleep (see Figure 1 for recommended sleep duration for different ages).[6]

Adults transition through 4-5 NREM to REM sleep cycles each night spending about 75% in NREM. Newborns, on the other hand, spend more time in REM. As babies age, their NREM time increases progressively.[7]

Sleep Habits[edit | edit source]

There are many different ways to develop good sleep hygiene for children. Below are some tips provided by raisingchildren.net.au:[8]

1. Bedtime routine

Starting a regular bedtime routine at around the same time every night has a positive impact on sleep patterns. A younger child's bedtime routine might consist of bath-time, a story and then bed. An older child's routine might include talking with parents about the day and some relaxing before turning their lights off.

2. Relaxing before bed

It is important that children relax before bed. For older children, this might mean reading books, listening to music or practising relaxed breathing techniques. Children who take longer than 30 minutes to fall asleep might need a longer "wind-down time" before they turn out the lights.

3. Regular sleep and wake times

It is important that a child goes to bed and wakes up at around the same time each day (i.e. within 1-2 hours). This helps to keep your child’s body clock in a regular pattern. It is a good idea to stick to this routine during weekends and holidays, as well as school days.

4. Early and short naps for older children

Most children will stop having naps between the ages of 3 and 5 years. If a child aged over 5 still naps, the nap will ideally be less than 20 minutes and happen before the early afternoon. If naps are longer / later, it may be harder for a child to get to sleep in the evening.

5. Ensure children feel safe at night

If a child is scared of the dark or going to bed, it can help to praise / reward a child when they are brave. It can also be beneficial to avoid scary TV shows, movies and computer games.

6. Consider noise and lighting in a child’s bedroom

It is important to make sure that a child’s bedroom is not too light or noisy for sleep. Blue light from TVs, computer screens, phones and tablets has a negative impact on sleep as it suppresses melatonin levels, thus delaying sleepiness. Being exposed to bright light one hour before bed has a similar impact on small children.

The following strategies can be helpful:

- Make sure all devices are turned off at least one hour before bedtime

- Do not have screens in a child’s room overnight

- If possible, dim the lights one hour before bedtime for children aged less than 5

If a child uses a night-light, dim, warm-coloured lights are better than bright, white / cool-coloured lights.

7. Avoid watching the clock

If a child is regularly checking the time at bedtime, it is useful for them to move their clock or watch, so they cannot see it from bed.

8. Eating the right amount of food at the right time

Children should have a "satisfying evening meal at a reasonable time". Feeling too full or hungry before bed might make a child feel more alert / uncomfortable, thus making it harder to go to sleep. Similarly, having a healthy breakfast in the morning will help to regulate a child's body clock.

9. Natural light during the day

It is important that children get as much natural light as possible each day, especially during the morning. Bright light suppresses melatonin, so that a child will feel awake and alert during the day, but sleepy at bedtime.

10. Avoid caffeine

Children should be encouraged to avoid caffeine in the late afternoon and evening (i.e. energy drinks, coffee, tea, chocolate, cola etc).[8]

Children, technology and Sleep[edit | edit source]

Many studies have been done on the use of technology in children's and teens' bedrooms and its adverse effect on sleep. Mustafaoğlu et al.[9] has summarised some of the findings below:

- “Keeping a television, computer, or mobile phone in the bedroom during early childhood is associated with less sleep

- Children who make excessive use of social media or who sleep with mobile devices in their bedrooms are at increased risk of experiencing sleep disturbances

- Poor sleep quality in adolescents is associated with extreme mobile phone use while the number of devices in a bedroom and poor sleep quality are associated with excessive internet use and duration of digital technology usage prior to sleep in pre-adolescents

- The use of electronic devices during the daytime can also affect sleep quality”[9]

Pillar 2: Diet[edit | edit source]

Children need to eat vegetables and fruit to maintain a healthy diet. In Australia, it is recommend that children aged 4-8 years old consume 4.5 vegetables and 1.5 pieces of fruit daily. Children aged 9-11 years should consume 5 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruit daily. Because fruit is sweeter, children are often less likely to dislike fruit than vegetables.[10] Encouraging children to eat the "rainbow" ensures their intake includes a variety of vitamins and mineral.[5]

Please check the specific dietary recommendations for children in your country / community.

Pillar 3: Movement[edit | edit source]

It is important for children to have movement time. It has been found that there is a link between movement and cognitive development.[11] Play experiences and new movement facilitates brain development and maintain neural connections. Limited activity can decrease brain cell connections. Coordination drills utilising both the left and right sides of the brain facilitate communication from one side to the other strengthening neural pathways that later help with language, maths and literacy skills. Even teenagers can promote further brain growth as the nervous system does not fully mature until the ages of 15-20.[11]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- Holistic healthcare encompasses the physical, mental, spiritual, emotion and social well-being of the individual rather than focusing on one element

- Understanding the pillars of health and looking at a child from a holistic perspective ensures the clinicians gets an overall snapshot of their health and highlights what areas need addressing to ensure well-being

Resources[edit | edit source]

- NJAAP Children's sleep habit questionnaire

- PSWQ-C Worry questionnaire

- RCADS-P25 Caregiver questionnaire

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mcilroy T. What are the 5 Aspects of Holistic Development in Childhood? [Internet]. Empowered Parents [cited 16 March 2022]. Available from: https://empoweredparents.co/what-are-the-5-aspects-of-holistic-development/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Dhabhar FS. The short-term stress response–Mother nature’s mechanism for enhancing protection and performance under conditions of threat, challenge, and opportunity. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2018 Apr 1;49:175-92.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 LeBouef T, Yaker Z, Whited L. Physiology, Autonomic Nervous System. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1.

- ↑ Stanković I, Adamec I, Kostić V, Habek M. Autonomic nervous system—Anatomy, physiology, biochemistry. InInternational Review of Movement Disorders 2021 Jan 1 (Vol. 1, pp. 1-17). Academic Press

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Prowse T. Holistic Interventions for Children Course. Physioplus. 2022.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ramar K, Malhotra RK, Carden KA, Martin JL, Abbasi-Feinberg F, Aurora RN, Kapur VK, Olson EJ, Rosen CL, Rowley JA, Shelgikar AV. Sleep is essential to health: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2021 Oct 1;17(10):2115-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Gobbi G, Comai S. Differential function of melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors in REM and NREM sleep. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2019:87.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 How to sleep better:10 tips for children and teenagers. Available from: https://raisingchildren.net.au/toddlers/sleep/better-sleep-settling/sleep-better-tips (accessed 16 March 2022).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mustafaoğlu R, Zirek E, Yasacı Z, Özdinçler AR. The negative effects of digital technology usage on children’s development and health. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions. 2018;5(2):13-21.

- ↑ Thurber KA, Banwell C, Neeman T, Dobbins T, Pescud M, Lovett R, Banks E. Understanding barriers to fruit and vegetable intake in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children: a mixed-methods approach. Public health nutrition. 2017 Apr;20(5):832-47.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 PennState Extension. Movement builds a child's brain. Available from: https://extension.psu.edu/movement-builds-a-childs-brain (accessed 16 March 2022).